|

We have a robust selection of therapies that allows us to treat the root cause of most signs and symptoms of dry eye disease. However, despite the countless innovations, most patients still experience occasional rapid-onset flareups that cannot be adequately managed with the patient’s usual maintenance therapy. Fortunately, current options can reduce the risk of a flareup and can control one quickly when it does arise—and new approaches to rescue therapy may soon provide patients with on-demand relief.

Symptoms Come and Go

Although dry eye is a chronic condition, symptoms tend to wax and wane. For example, dry eye can spike during allergy season, when a patient stops using prescription drops or when a systemic drug is prescribed for another condition. Sometimes, symptoms present for no apparent reason whatsoever.

In a recent survey of 503 patients diagnosed with dry eye, 80% to 90% said they experience flares about six times per year.1 As primary eye care providers, it’s up to us to offer relief for acute presentations as quickly as possible. The longer a flareup persists, the harder it is to control. Flareups can cause significant distress, especially if patients have to wait several days for an appointment.

Patients who present with a dry eye flareup often have red eyes, lid involvement and increased staining. Physiologically, the eye is trying to heal itself by mounting an inflammatory response, but this can take several days and have long-lasting effects on the ocular surface, the tear film, corneal sensitivity and more.

In the meantime, the patient’s discomfort often leads to blink alterations, which further exacerbate symptoms and can perceptibly compromise visual function.2

|

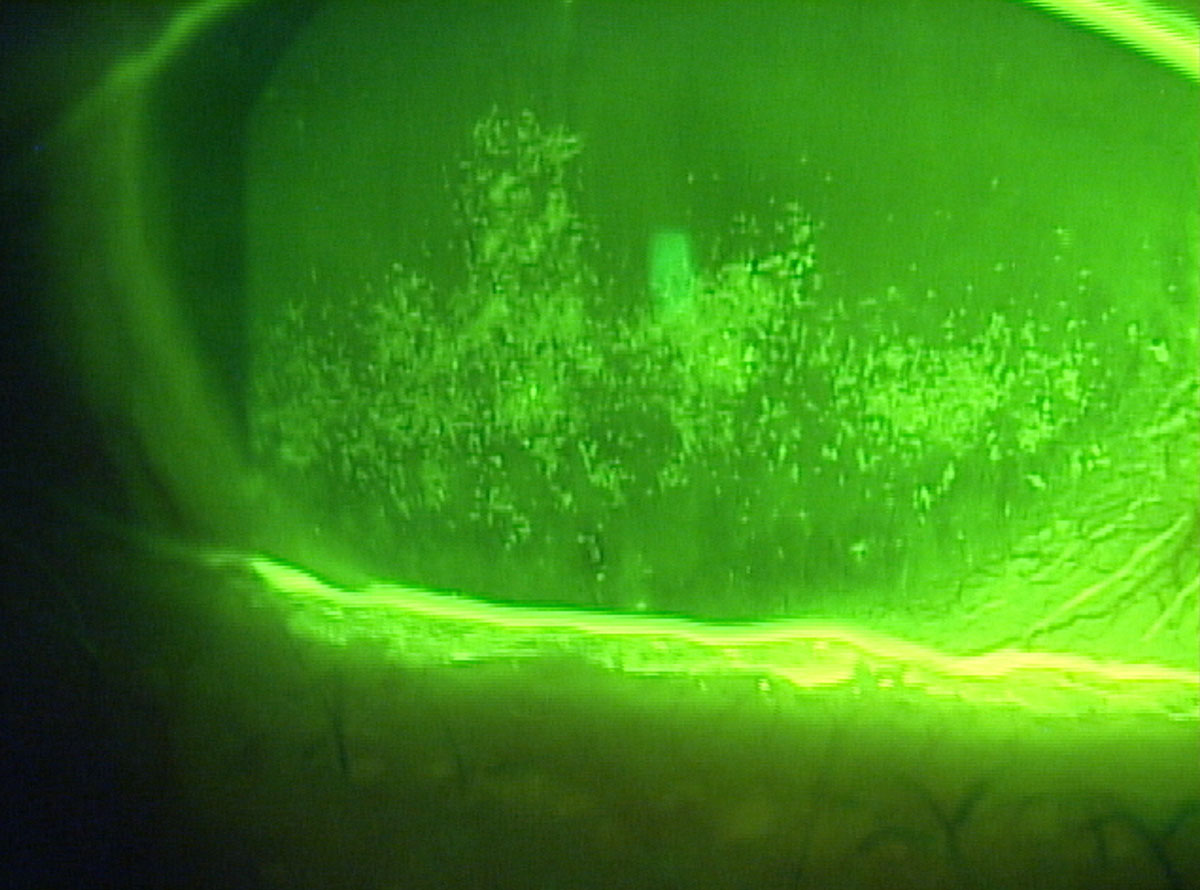

| Dry eye patients with confluent superficial punctate keratitis may need an arsenal of rescue therapy options. Click image to enlarge. |

Rescue Therapy

Currently no treatments are no FDA-approved for short-term, rapid relief of episodic dry eye symptoms. As such, we generally rely on a steroid, allergy drop, biologic agents, ointments or other additive treatments to help shorten the episode and roll back symptoms. Just as almost every asthma patient receives an albuterol inhaler, all dry eye patients should have a plan for how to manage exacerbations. Here are a few good options:

Common Causes of Flareups

|

Over-the-counter (OTC). Although most patients experiencing dry eye flares require stronger therapeutics rather than OTC products, clinicians should recommend patients keep effective OTC options on hand. Having artificial tears and antihistamines (for those with a history of allergic conjunctivitis) in the medicine cabinet is a good recommendation. In addition, ocular hygiene supplies, such as a moist heat compress and hypochlorous acid spray, are must-haves. Bruder Healthcare also now packages a three-step hygiene kit that also includes wipes.

Masks and sprays can also offer that extra bump in comfort that patients crave in the midst of a dry eye flareup.

Neurostimulation. This new therapy can provide an instant release of one’s own tears by stimulating the trigeminal nerve. Our natural tears have more than 1,500 proteins, five lipid classes and 20 mucins, as well as growth factors and anti-inflammatory components.3,4 Stimulating the trigeminal nerve appears to impact all three tear-producing glands, including the goblet cells, meibomian and lacrimal glands.5-7

One recent FDA approval, the iTear100 neurostimulator (Olympic Ophthalmics) demonstrated a 22mm change in the Schirmer score when compared with sham with no device-related adverse events.

The Best Offense is a Good DefenseWe should do all we can to minimize the risk of flareups, including regular daily therapy such as cyclosporine or lifitegrast when appropriate. Regular in-office treatments also play a key role in reducing the potential for flareups, including: low-level light therapy for meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), chalazia, ocular rosacea and hordeola; Blephex for the treatment of the biofilm or blepharitis; and thermal pulsation/expression treatments for evaporative dry eye and MGD.1 In cases where signs such as punctate epitheliopathy escalate, initiating a biologic can make a significant difference for a patient. These include applying an amniotic membrane or prescribing autologous serum tears or cytokine extract drops.

|

In the Pipeline

Still, none of the available acute therapies eliminate flareups from reoccurring. But soon, new options may allow ODs to prescribe a form of rescue therapy for dry eye in much the same way allergists prescribe rescue inhalers for patients who have acute asthma attacks.

Kala has recently received FDA approval for Eysuvis (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.25%) with launch in the United States expected by the end of this year. Formerly called KPI-121, this formulation uses nanoparticles (approximately 300nm) engineered to penetrate through mucus pores to the ocular surface without being eliminated by the tear film. However, this mechanism more than triples the loteprednol etabonate penetration to the cornea and aqueous humor.

The STRIDE 3 study compared 447 patients in the Eysuvis treatment group and 454 patients receiving the vehicle, each dosed four times a day for two weeks.8

Ocular discomfort severity was graded daily by the patient using a visual analog grading scale that ranged from 0mm to 100mm.8

The results demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in ocular discomfort severity from baseline to day 15 compared with the controls in both the overall population and a pre-defined subgroup of patients. The subgroup presented with more severe baseline ocular discomfort, defined as patients who scored greater than or equal to 68mm in baseline ocular discomfort.3

Statistical significance was also achieved in conjunctival hyperemia at day 15 in the overall population and ocular discomfort severity at day eight in the study population. Significant results were also observed for total corneal staining at day 15.8

Eysuvis was well-tolerated, and the most common adverse event was instillation site pain in 2.9% of the Eysuvis patients and 1.5% in the vehicle group. Elevations in intraocular pressure were similar between the two groups.8

Another potential future option is varenicline (Oyster Point Pharmaceuticals), a nasal spray that involves nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to stimulate the trigeminal nerve, affecting the parasympathetic nervous system. ONSET-2, a phase III clinical trial, was a real-world type study with no placebo run-in and a broad range of dry eye signs and symptoms.9 Although the study was cut short due to COVID-19, it met the statistical end point of a greater percentage of patients having ≥10mm change from baseline in Schirmer scores. It also showed a statistically significant improvement in dryness symptoms.

Not only do these new treatments bring rescue therapy to the forefront, but they also create a broader awareness about a shifting philosophy in terms of how we manage acute dry eye. Patients should be prepared for the fickle nature of dry eye with exceptional patient education and an arsenal of therapeutic options.

With new options on the way, you can help your patients be fully prepared to manage their next flareup promptly and effectively.

Note: Dr. Karpecki consults for companies with products and services relevant to this topic.

| 1. Kala. Patient survey; performed by a third party. 2. Ousler GW III, Abelson MB, Johnston PR, et al. Blink patterns and lid-contact times in dry eye and normal subjects. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:869-74. 3. Klenkler B, Sheardown H, Jones L. Growth factors in the tear film: role in tissue maintenance, wound healing, and ocular pathology. Ocul Surf. 2007;5(3):228-39. 4. Willcox MD, Argüeso P, Georgiev GA, et al. TFOS DEWS II tear film report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):366-403. 5. Dartt DA, McCarthy DM, Mercer HJ, et al. Localization of nerves adjacent to goblet cells in rat conjunctiva. Curr Eye Research. 1995;14(11):993-1000. 6. LeDoux MS, Zhou Q, Murphy RB, et al. Parasympathetic innervation of the meibomian glands in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2434-41. 7. Van Der Werf F, Baljet B, Prins M, et al. Innervation of the lacrimal gland in the cynomolgous monkey: a retrograde tracing study. J Anat. 1996;188(Pt3):591-601. 9. Oyster Point Pharma announces positive results in ONSET-2 phase 3 trial of OC-01 nasal spray for the treatment of the signs and symptoms of dry eye disease. https://investors.oysterpointrx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/oyster-point-pharma-announces-positive-results-onset-2-phase-3. May 11, 2020. Accessed October 22, 2020. 8. Kala Pharmaceuticals announces statistically significant results in STRIDE 3 trial of dry eye disease drug Eysuvis. Eyewire. eyewire.news/articles/kala-pharmaceuticals-announces-statistically-significant-results-in-stride-3-trial-of-dry-eye-disease-drug-eysuvis. March 20, 2020. Accessed October 22, 2020. |