Dry eye disease (DED) is a common presentation in eye care offices. Studies of the prevalence of DED vary significantly depending on the definition, the study population and the criterion for diagnosis. North American studies show a prevalence of symptomatic dry eye in males as low as 4.3%, and as high as 21.6% in the elderly.1,2

DED is often chronic and therefore requires ongoing management. However, patients are rarely prepared for the true complexity of the disease and the sometimes equally complex treatment plan. Unprepared patients are prone to noncompliance—the biggest obstacle for long-term therapy regimens such as those often required for dry eye.

These diagnostic, pharmaceutical and lifestyle tips can help you prepare DED patients for the therapy road ahead, and shift their mindset from one of burdensome treatment to ongoing eye care.

|

| TFOS DEWS II lists ocular surface staining, seen here with lissamine green, as an important diagnostic tool for dry eye—the first step in the management process. Photo: Jalaiah Varikooty, Centre for Contact Lens Research |

Gear up for the Challenge

The first step of dry eye management is a thorough diagnosis and categorization of the disease based on the new Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s (TFOS) Dry Eye Work Shop II (DEWS II) definition: “Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”3

As highlighted by this definition, dry eye is a complex disease that recently got even a little more complicated. In addition to the well-known fact that signs of DED don’t always correlate with symptoms, the newest aspect of the disease is the neurosensory component.3 Based on current literature, we now know that some patients can present with pristine-looking ocular surfaces but suffer from dry eye symptoms that are, in fact, a neuropathy.4 We refer to these patients as having “pain without stain.” In these cases, a diagnosis of pre-clinical ocular surface disease (OSD) or neuropathic pain—not DED—comes long before clinical signs.

To get to the bottom of a patient’s dry eye symptoms, clinicians should follow the TFOS DEWS II essential diagnostic test recommendations: a dry eye questionnaire followed by tear break-up time (TBUT, noninvasive diagnosis <10sec, F-BUT diagnosis <5sec), osmolarity (diagnosis ≤308mOsm/L) and ocular surface staining (diagnosis >5 corneal spots or conjunctiva >9 spots).5 Not all testing is available to each clinician, and only one of these tests needs to be abnormal to move the diagnosis forward.

The categorization of DED is also integral to direct treatment, and it help the patient better understand the mechanism underlying their particular form of dry eye, whether it’s aqueous deficient, evaporative or a mixture of the two. Clinicians can determine much of this by measuring the tear meniscus height (categorized as mild with 0.2mm, moderate with 0.1mm and severe with 0.0mm) and analyzing meibomian gland function (graded as mild, moderate or severe). Treatments usually begin in a step-like manner going from simple to complex, depending on the severity of the condition and the response to treatments. At the end of a dry eye workup, the clinician will have not only the diagnosis, but also valuable information about its etiology, severity and any meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).

Armed with this information, clinicians should then spend time properly educating the patient. Whether it’s a female, age-related post-menopausal dry eye, an aqueous deficient dry eye related to an autoimmune disease such as Sjögren’s syndrome or strictly a meibomian gland disease, that information is invaluable for patients. When they understand the particular characteristics of their disease state, they are more likely to comply with the treatment.

|

| Patients are confronted with a multitude of lubricating drops at the drug store. It’s the OD’s job to help them narrow their options. |

Climbing the Management Mountain

Dry eye therapy is often incredibly daunting to patients. Most people are familiar with diseases treated with a course of medication, surgery or a few weeks of palliative measures as their body fights off the untreatable virus. Unfortunately, dry eye tends to be chronic and patients must understand that they are in for a lifetime of care. I liken this new eye care approach to that of their dental care. Without thinking, most of us floss, brush and see our dentist regularly. Similarly, all patients, and dry eye patients in particular, need to care for and maintain a healthy ocular surface over their lifetime.

A second barrier to compliant dry eye care is the cost. Topical over-the-counter lubricants can cost as much as $50 per bottle, and the cost of prescription medications such as Restasis (cyclosporine, Allergan) and Xiidra (lifitegrast, Shire) can overwhelm the patient. Both of these factors play an important part in the patient’s decision to adhere to the treatment plan you discuss with them.

Lubricants. In almost every form of DED, a lubricant is needed. However, the sheer number of ocular lubricants on drug store shelves is overwhelming. Patients need guidance in choosing the correct product for their specific form of dry eye, especially regarding generic brands, in which the preservatives often differ from branded products. For example, patients with predominantly MGD-induced evaporative dry eye will likely do better with a lipid-based drop, at least until those glands are functioning normally.

For those who do not need the extra lipid or those who do not do well on a lipid-based drop, the biggest decision is whether to recommend preserved or non-preserved drops. Clearly, benzalkonium chloride (BAK) should be avoided if possible, but the effects of other preservatives have yet to be studied on a clinical level. The rising trend is to use non-preserved drops, a clinical wisdom without clear clinical scientific evidence. In theory, preservative free formulations eliminate one possible irritant; in practice, many of the new preservatives seem to work well for patients and the formulations are often less expensive.

The problems associated with the use of BAK-preserved drops are well-known, and this preservative should be avoided if possible.6-9 However, we do not have comparative studies that show the ocular insult associated with other “modern” preservatives such as polyquad, sodium perborate, Purite, Ocupure and PHMD. In addition, ridding a drop of preservatives does not negate the effect of the active ingredients, which can themselves be toxic.

While choosing a non-preserved drop eliminates any iatrogenic toxic complication from preservatives, the cost can be overwhelming. My particular style is to begin with a preserved, less expensive drop to first understand the treatment effect on that particular patient. This starts the patient at the lowest end of the treatment scale: easy, effective (hopefully) and inexpensive. Carrying a bottle of artificial tears in a purse or pocket is much easier and safer than carrying a unit-dose vial that has been opened and will be reused during the day, whether we like it or not.

If a non-preserved drop is necessary, clinicians must emphasize to the patient that the extra cost is warranted. Most patients are aware that their sensitive eyes need special care.

Compliance is always a problem when expense is considered. Reminding patients that using drops for dry eyes is the same as using creams for dry skin can be helpful. Many patients understand quite well that moisturizing cream does not go on once and solve the problem. It must be applied daily, and many also use a night cream as well.

The prescription medications Restasis and Xiidra are expensive for those without drug plans. If a patient’s treatment plan includes these medications, the manufacturers have provided cost-reduction cards to most practitioners to help offset the cost. Cost limitations may prompt patients to use one vial per day—once in the morning and again at night—rather than two vials per day as instructed. However, this is risky because of the non-preserved nature of the vials. The new Restasis multidose non-preserved bottle would be a safer choice.

|

| Conventional therapy for most patients with MGD includes warm compresses and lid massage. Photo: Alan G. Kabat, OD, and Joseph W. Sowka, OD |

Lids. Evaporative dry eye is the most prevalent form of DED, and MGD is one of the most common causes. Researchers have studied the prevalence of MGD outside the United States and have found it as low as 30.5% in Spain and as high as 68.3% in China.10,11

When dysfunctional, the meibomian glands can be treated with massage and heat. However, achieving the necessary 40° Celsius (roughly 104° Fahrenheit) heat for at least 10 minutes is no easy task without expenditures.12 Several eye masks work well that can be heated in the microwave, but some are expensive and usually last no more than one year. More affordable masks, such as the TheraPearl eye mask (Bausch + Lomb), often work well.

Also, if cost is a factor, patients can use hot water compresses with a clean face cloth, but they will invariably struggle to keep the temperature at 40°C. Other methods to keep the temperature up longer, such as using tea bags, rice in a sock and potatoes wrapped in cloths, may help, but have a tendency to overheat. Clinicians should counsel patients accordingly if they express interest in these alternatives.

Cleaning lashes and massaging the oil glands are both integral to MGD and anterior blepharitis treatment. Many excellent and expensive lid wipes exist, including those with medicinal additives such as tea tree oil. Patients unwilling to use these items can use their clean fingers and a lubricant face wash, such as off-label Spectro Jel (GlaxoSmithKline), to clean their lids in the shower. A toothbrush-like back and forth motion of scrubbing the lids while counting to 10 and then rubbing the base of the glands at the orbital side of the lids helps to clean lashes and massage the meibomian glands.

Clinicians should keep in mind that studies now show that baby shampoo does not solve anterior blepharitis and may make it worse, as it often contains cocamidopropyl betaine, a surfactant and lathering agent that can cause eyelid dermatitis.13,14

Oral supplements. For years we have prescribed omega-3 fatty acids (FA) for MGD and dry eye. Recently, the DREAM study has changed how we see this practice.15 Basically, the study demonstrated that the particular FA supplements used in the well-designed trial did not help MGD any more than the sham pills that contained small amounts of olive oil determined to be easily met by most North American diets. With the heart community also finding little benefit to omega-3 supplements, many practitioners are discontinuing that recommendation.16 Patients probably won’t complain, considering the high cost of these supplements.

Environment. Many environmental changes are inexpensive and particularly effective. Patients should use wraparound glasses and sunglasses when outside to prevent wind current from drying the eyes. In our office, we keep examples of Pantoptix glasses and other forms of protection such as Cocoon (Live Eyewear) that can be worn over regular glasses.

A small humidifier placed on the work desk can reduce dryness and artificial tear use while using the computer. If cost is a factor, a bowl of water with as much surface area as possible will also add moisture to the air. Patients should redirect any vents in the room away from their face.

For patients who use a computer throughout the day, clinicians should recommend they sit a little higher in their chair or lower the desk to ensure the gaze down at the computer. This allows the upper lid to cover more of the ocular surface, thus protecting more cells and thickening the tear film.

Blinking is free, as are several easy blinking exercise apps. Patients should adhere to the 20/20/20/20 rule: every 20 minutes take 20 seconds to look 20 feet away and blink 20 times. For those who struggle to incorporate regular blinking exercises, free apps, such as such as the Donald Korb Blink Training App (TearScience) and EyeLeo, encourage proper blinking with reminders and proper pacing.17,18

Patients should always keep airflow away from their eyes to avoid exacerbating dry eye. Counsel them to avoid long-term exposure to ceiling and box fans (especially at night) and to keep the heat and air conditioning in the car at their feet, not in their face.

|

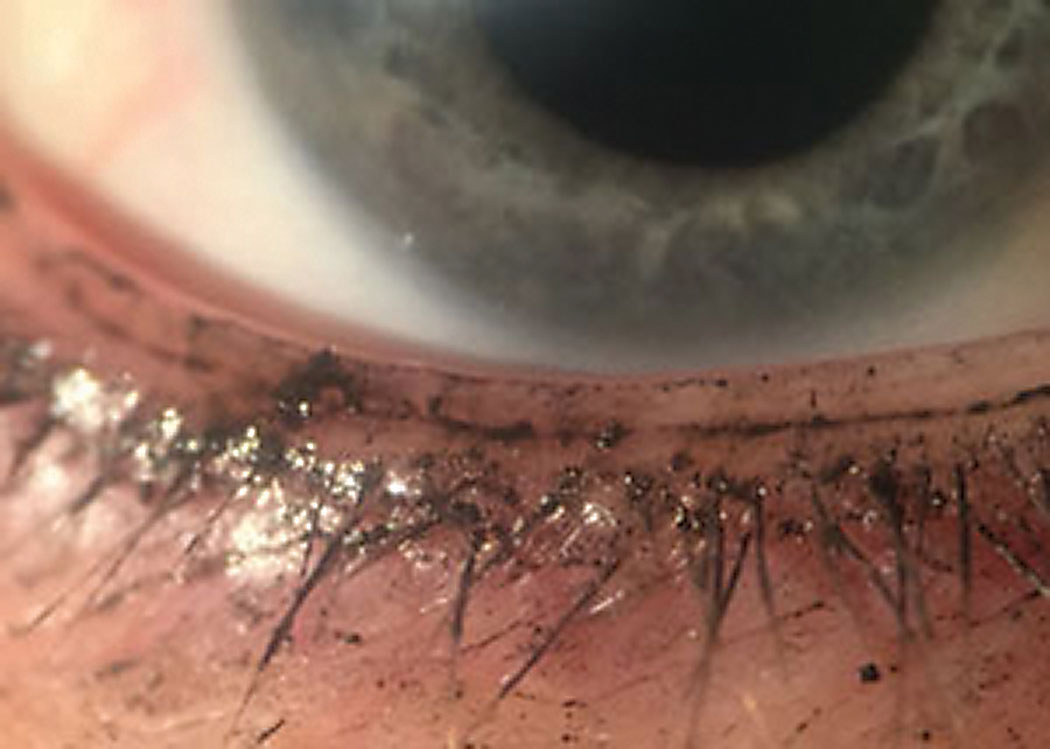

| Even when applied properly, makeup debris can migrate to the lid and conjunctiva, contributing to dry eye symptoms. Photo: Leslie O’Dell, OD |

Lifestyle. Those who smoke should be counseled on the myriad benefits of quitting, including the benefits for their ocular health. Research shows tobacco smoke can exacerbate dry eye, as it causes tear film instability and increases ocular surface staining.19-21 In fact, one study found patients who smokers are nearly twice as likely to have dry eyes.20 Encouraging smoking cessation and avoidance of smoke will save them a fortune and prolong their life.

Getting enough sleep is an inexpensive way to help protect the eyes from symptoms of dry eye.22 Oversleeping is unnecessary, but getting enough sleep is essential, as one study found 45% of dry eye patients reported poor sleep quality.23 Other researchers conducted focus group sessions with 38 patients with dry eye to better understand their various coping methods and found sufficient, good-quality sleep helped many participants.24

Patients should go to bed at regular hours and keep the bedroom moist with pans of water or a humidifier. A recent study also suggests sleep position may play a small part in dry eye symptoms. Researchers found elevated Ocular Surface Disease Index scores in patients who slept on their sides compared with those who slept on their back and a statistically significant difference with back sleeping compared with left side sleeping using lissamine green staining.25 Clinicians can consider recommending patients try to adjust their habitual sleeping position to better protect their eyes from overnight drying.

Also, those who use a continuous positive airway pressure machine for obstructive sleep apnea may experience worse dry eye in the morning, as air can leak from the mask directly onto the ocular surface. These patients can use goggles to protect the eyes overnight and minimize ocular involvement.

Cosmetics can cause or exacerbate any number of ocular issues, including dry eye. Patients should never wear eyeliner inside the lash line, as it can plug the meibomian glands and cause inflammation. In addition, many eyeliners use BAK as the preservative, which, when it remains in contact with the lid cells, can cause damage.26 Clinicians should counsel patients to take all of their makeup off before bed, and use a soft cloth to wipe and massage the lids as they remove the makeup.

Hydration is important for everyone, but especially for dry eye patients. Although a simple recommendation, asking patients to remember to drink plenty of water and avoid diuretic drinks like alcohol and coffee can have a significant impact on ocular dryness.27

As inflammation is a known part of dry eye, an anti-inflammatory diet may be worth recommending to patients in search of alternative dry eye remedies.28 Fresh food with few additives as described in the mayo Clinic diet may make a difference to joints and the eyes.

Dry eye disease requires a concerted effort on the patient’s part to modify their external and internal environment to help encourage ocular health. It also requires regular use of lubricants and lid care. Optometrists serve their patients well if they diagnose, and then educate them about the type and degree of dry eye that is present. Time spent explaining the options for treatments that include less expensive forms, is time well spent to improve patient outcomes.

Dr. Caffery practices at Toronto Eye Care in Toronto. She also participates in two hospital-based clinics: the University Health Network Multidisciplinary Sjögren’s Syndrome Clinic and the Therapeutic Contact Lens Clinic at Kensington Eye Institute. She has served on the Board of Directors of the American Academy of Optometry since 2006 and is the current president. She has also served on the Medical Advisory panel of the Sjögren’s Society of Canada since 2008.

1. Schaumberg D, Dana R, Buring J, Sullivan D. Prevalence of dry eye disease among us men: estimates from the physicians’ health studies. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:763-8. 2. Moss S, Klein R, Klein B. Long term incidence of dry eye in an older population. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:668-74. 3. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276-83. 4. Belmonte C, Nichols JJ, Cox SM, et al. TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):404-37. 5. Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):539-74. 6. Chung SH, Lee SK, Cristol SM, et. al. Impact of short-term exposure of commercial eyedrops preserved with benzalkonium chloride on precorneal mucin. Molecular Vision. 2006;12:415-21. 7. Lin Z, He H, Zhou T, et al. A mouse model of limbal stem cell deficiency induced by topical medication with the preservative benzalkonium chloride. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(9):6314-25. 8. Chen W, Zhang Z, Hu J, et al. Changes in rabbit corneal innervation induced by the topical application of benzalkonium chloride. Cornea. 2013;32(12):1599-1606. 9. Pinheiro R, Panfil C, Schrage N, Dutescu RM. The impact of glaucoma medications on corneal wound healing. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(1):122-7. 10. Viso E, Gude F, Rodriguez-Ares M. The association of meibomian gland dysfunction and other common ocular diseases with dry eye: apopulation based study in Spain. Cornea. 2011;30:1-6. 11. Jie Y, Xu L, Wu Y, Jonas J. Prevalence of dry eye among adult Chinese in the Bejing Eye Study. Eye (Lond). 2009;23:688-93. 12. Olson MC, Korb DR, Greiner JV. Increase in tear film lipid layer thickness following treatment with warm compresses in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction. Eye Contact Lens. 2003;29(2):96-9. 13. Welling JD, et al. Chronic eyelid dermatitis secondary to cocamidopropyl betaine allergy in a patient using baby shampoo eyelid scrubs. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):357-9. 14. Sung S, Wang MTM, Lee SH, et al. Randomized double-masked trial of eyelid cleansing treatments for blepharitis. The Ocular Surface. 2018;16:77-83. 15. Maguire M, Asbell P, Group DSR. N-3 fatty acid supplementation and dry eye disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1681-90. 16. Abdelhamid A, Brown T, Brainard J, et al. Omega 3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane. 2018;7:Cd003177. 17. Korb Blink Training App. itunes.apple.com/us/app/donald-korb-blink-training/id941412795?mt=8. Accessed August 30, 2018. 18. Eyeleo PC application. eyeleo.com. Accessed August 30, 2018. 19. Thomas J, Jacorb GP, Abraham L, Noushad B. The effect of smoking on the ocular surface and the precorneal tear film. Australas Med J. 2012;5(4):221-6. 20. Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2000;118(9):1264-8. 21. Xu L, Zhang W, Zhu X, et al. Smoking and the risk of dry eye: a meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9:1480-6. 22. Lee W, Lim SS, Won JU, et al. The association between sleep duration and dry eye syndrome among korean adults. Sleep Medicine. 2015;16:1327-31. 23. Kawashima M, Uchino M, Yokoi N, et al. The association of sleep quality with dry eye disease: the Osaka study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1015-21. 24. Yeo S, Louis Tong L. Coping with dry eyes: a qualitative approach. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:8. 25. Alevi D, Perry HD, Wedel A, et al. Effect of sleep position on the ocular surface. Cornea. 2017;36:567-71. 26. Chen X, Sullivan D, Sullivan A, et al. Toxicity of cosmetic preservatives on human ocular surface and adnexal cells. Exp Eye Res. 2018;170:188-97. 27. Caffery B. Influence of diet on tear function. Optom Vis Sci. 1991;68:58-72. 28. Sears B. Anti-inflammatory diets. J Am Coll Nutr. 2015;34:14-21. |