|

A 74-year-old African-American male presented with a chief complaint of redness and pain in both eyes of two days’ duration. His ocular history was remarkable for bilateral cataract extraction, which had been performed two years prior.

His systemic history included diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and a recent diagnosis of multiple myeloma, for which he was started on a new medication. His systemic medications included glipizide, Humalog (insulin lispro), lisinopril, metoprolol, simvastatin, prochlorperazine maleate, Velcade (bortezomib), dexamethasone and Zometa (zoledronic acid).

Clinical Findings

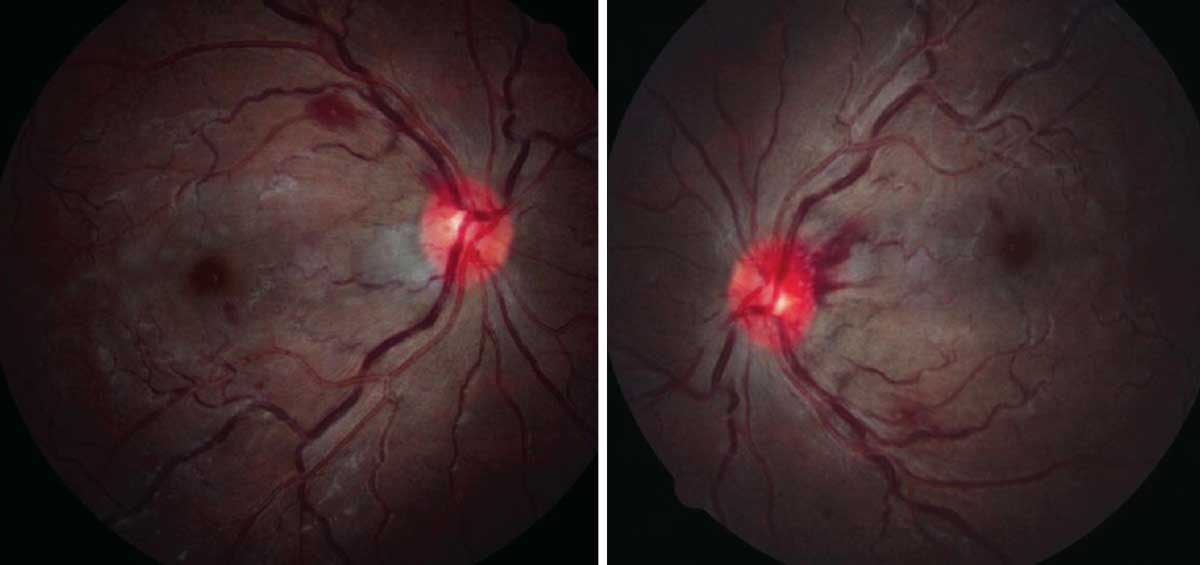

His best-corrected visual acuities were 20/20 OD and OS at distance and near. All external testing was unremarkable and there was no afferent defect. Slit lamp exam revealed Grade 1+ conjunctival injection OU and Grade 2+ cells with trace flare and ciliary flush OU. Intraocular pressures were measured at 9mm Hg OD and 10mm Hg OS by Goldmann applanation. The significant dilated fundus findings are demonstrated in the photographs.

|

Fundus evaluation revealed these findings. What do these images suggest about his status? What laboratory results might you expect based on this presentation? Click to enlarge. |

Additional laboratory work up is indicated for both the anterior segment and retinal findings, especially in the present of his considerable medication regimen. The recommended blood panel would include:

- complete blood count with differential and platelets (CBC c Diff and platelets)

- chest x-ray (CXR)

- human leukocyte antigen test (HLA B27)

- reactive plasma reagin test (RPR)

- fluorescent-Treponemal antibody absorption study (FTA abs)

- angiotensin-converting enzyme study (ACE)

- rheumatoid factor (RF)

- lipid profile

- fasting blood sugar (FBS) level

- human immunodeficiency virus assay (HIV titre)

- assay of clotting factors (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time)

Blood sugar and glycosylated hemoglobin should also be measured.

Sorting it Out

The diagnosis in this issue is bilateral non-granulomatous iritis as a secondary consequence of multiple myeloma (MM) treatment.

Multiple myeloma is a neoplastic process characterized by the proliferation of lymphoplasmacytic cells in the bone marrow.1-6 The condition is responsible for the production of immunoglobulin antibodies which lead to excessively high levels.3 The disease is characterized by generalized fatigue, weight loss, anemia, hypercalcemia and bone pain.1-6 It may also present asymptomatically, being discovered serendipitously.6

As plasma cells accumulate, metastasis and infiltration are possible in all organ systems, with common involvement of the ocular adnexa.1-6 The literature documents that sequalae may occur in almost any ocular tissue, ranging from recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhages, anterior segment depositions and profound inflammation to cranial nerve palsies and hyperviscosity retinopathy.3 Ocular findings may be among the first manifestations of multiple myeloma and may indicate failure of the systemic treatment.2

Complications secondary to multiple myeloma occur mainly via two mechanisms: either by direct tissue infiltration of the plasma cells or by hematologic processes.6 Ocular sequelae may also result as an adverse effect of the systemic therapy itself.7

The infiltration of monoclonal B cells into the anterior chamber results in the breakdown the blood-aqueous barrier, producing inflammation in the uveal structures.3 In recent studies, the cytology of the aqueous material in MM patients presenting with uveitis and pseudohypyon was examined, revealing the presence of monoclonal kappa immunoglobulin, confirming this infiltration model.7

Research has also recognized certain chemotherapies as initiators of the cascade of inflammatory events, instigating the development of a uveitis.8 The literature describes ocular symptoms generally occurring soon after treatment is administered, corresponding to the spike of proinflammatory agents, which ultimately spill over into immune-privileged sites.9

In the retina, a hyperviscosity syndrome may manifest from the proliferation of monoclonal immunoglobulin into the bloodstream.5 An elevated plasma viscosity ensues with the increased protein content. This along with other hematologic changes and irregularities results in retinal vascular abnormalities, retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms and cotton wool spots.3

The general differential diagnoses for anterior uveitis include HIV, sarcoid, tuberculosis, lyme, lupus, rheumatologic conditions and syphilis. The retinopathy differential includes diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, hyperviscosity/coagulopathy retinopathy, dyslipidemia disease, cardiac and carotid disease.1-6

Lab Findings

The diagnosis of multiple myeloma was confirmed by the presence of plasma cells in the blood and urine. The treatment for MM has significantly advanced over the past decade. A bone marrow biopsy revealed absent iron reserves with 40% kappa clonal plasma cells, which confirmed a diagnosis of Stage III multiple myeloma. Chemotherapeutic agents, mainly bortezomib (Velcade, Millennium pharmaceuticals), dexamethasone (Rising Pharmaceuticals) and zoledronic acid (Zometa, Novartis) were initiated less than a week prior to the ocular presentation.

Original therapies have included conventional or high-dose chemotherapies and interferon. Other commonly used therapies include bortezomib, thalidomide, lenalidomide, oral and intravenous corticosteroids and radiation therapy, directed towards a localized lesion of plasma cell infiltration.1-10 Newer treatments have recently evolved with the use of bisphosphonates (Zometa), which inhibit bone resorption, and erythropoietin, which aides in the manufacture of red blood cells and stem cell transplantation.1-10 A combination of these therapies are initially used and repeated in the case of relapse.1

Treatment and Prognosis

The bilateral uveitis was treated with prednisolone acetate 1% Q2h OU and atropine 1% BID OU. Follow-up was scheduled in three days to reassess the ocular condition and complete IOP monitoring. Following a prompt response to this therapy, the topical medications were tapered over a six-week period. A dilated fundus examination was performed at each subsequent visit to monitor the resolution of acute retinopathy. Correspondence with the medical team resulted in improved systemic management and resolution of the uveitis and retinopathy in six weeks.

It is unclear whether the uncontrolled neoplastic process induced the inflammation or if it was the medications. Since treatment was initiated just days preceding the symptoms, a concomitant reaction to the chemotherapy was included in the decision making. The systemic team suggested the clinical manifestations indicated the need for more aggressive and intensive systemic therapy.

It is arguable that the acute presentation was due solely to the hematologic complications of multiple myeloma. However, the history of diabetes and hypertension for five years with no ophthalmoscopic evidence of retinopathy or vasculature abnormalities noted up until the event suggested the pathology was treatment provoked by the addition of the meds.

A bilateral anterior uveitis may be the initial presenting sign in cases of multiple myeloma. All cases of bilateral uveitis require a thorough workup and proper lab testing, with correspondence to the medical team. Ocular inflammation may also signal complications with the systemic treatment strategy, precipitating a need for reassessment.

Ophthalmic examination in patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma should be performed both at the initial time of diagnosis to determine whether control of the neoplastic process has been achieved as well as routine examinations thereafter, given the high potential for relapse. Since ocular involvement in nearly any ophthalmic structure has been noted in the literature, routine ocular evaluation is necessary for earlier detection of ineffective control or any potential relapse.

Dr. Gurwood is a professor of clinical sciences at The Eye Institute of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. He is a co-chief of Primary Care Suite 3. He is attending medical staff in the department of ophthalmology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Bataille R, Harousseau, JL. Multiple myeloma. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336(23): 1657-64. 2. Kottler UB, Cursiefen, C, Holbach LM. Orbital involvement in multiple myeloma: first sign of insufficient chemotherapy. Ophthalmoligica. 2003;217(1):76-78. 3. Omoti, AE, Omoti, CE. Ophthalmic manifestations of multiple myeloma. West African Journal of Medicine. 2007;26(4):265-268. 4. Gray RH, Tighe M, Russell NH. Rapid onset retinopathy in a diabetic patient following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2000;26(6):695-696. 5. Pelino CJ, Pizzimenti J. A hematological malignancy: ophthalmic manifestations of multiple myeloma are diverse and may appear at any time in the disease process. Review of Optometry. 2009;146(11):98. 6. Fung S, Selva D, Leibovitch I, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations of multiple myeloma. Ophthalmologica. 2005:219(1):43-48. 7. Tranos P. Andreou P, Wickremasinghe SS, Brazier J. Pseudohypopyon as a feature of multiple myeloma. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2002;120(1):87-88. 8.Durnian JM, Olujohungbe A, Kyle G. Bilateral acute Uveitis and conjunctivitis after zoledronic acid therapy. Eye 2005;19(2):221-222. 9. Kilickap S, Ozdamar Y, Altundag KM, Dizdar O. A case report: zoledronic acid-induced anterior uveitis. Medical Oncology. 2008;25(2):238-240. 10. Singhal S, Mehta J. Moving points in nephrology: multiple myeloma. American Society of Nephrology. 2006;1(6):1332-1330. |