|

|

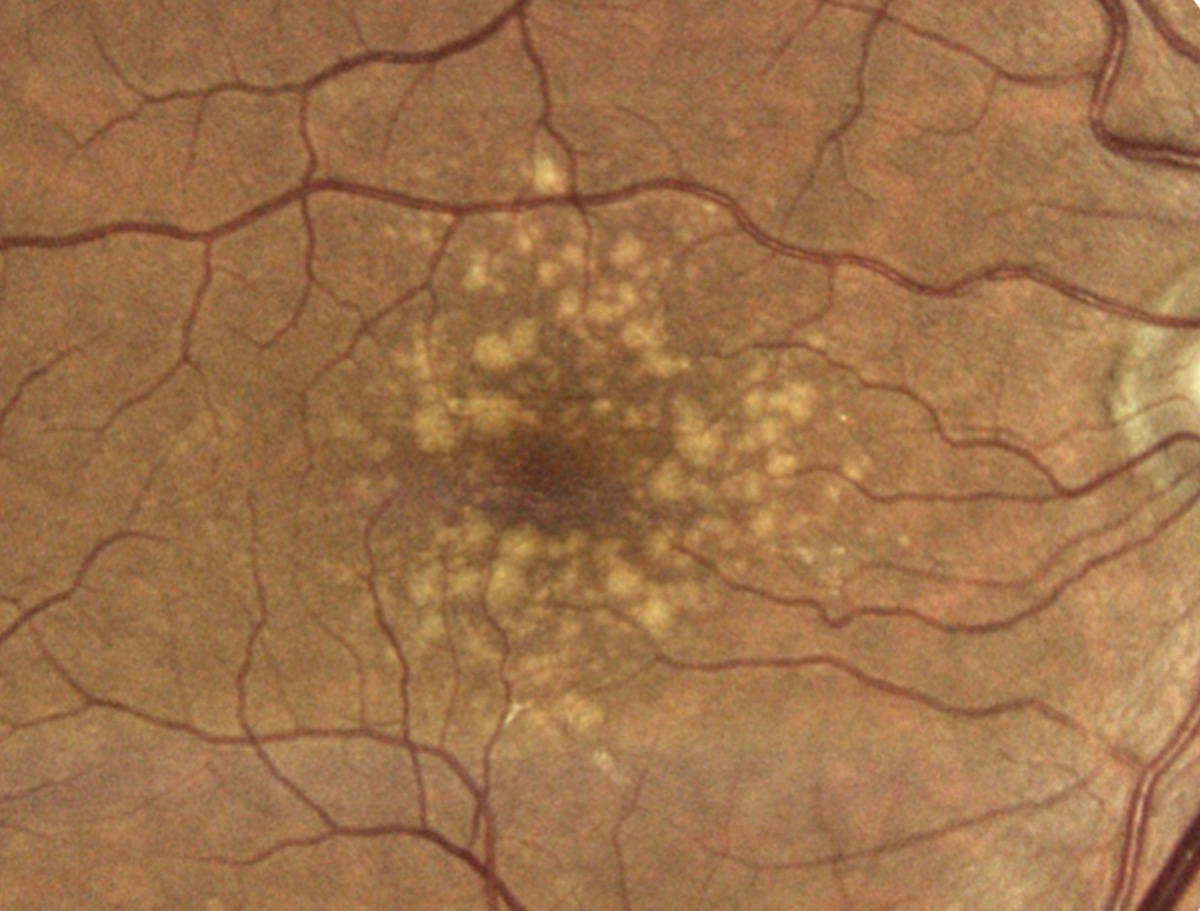

Low-dose aspirin was not found to have any benefit for AMD, although evidence was weaker for progression of AMD due to low numbers of cases that progressed. Photo: Jessica Haynes, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Although treatments that restore vision lost from age-related macular degeneration (AMD) have flourished in the nearly two decades since the advent of anti-VEGF agents, there remains no proven intervention that can prevent onset on a widespread scale. Clinicians are left to advising patients on lifestyle modifications, including dietary changes and considerations of AREDS supplements when appropriate. Aspirin, it seems, will be no help either.

That intervention was explored in a new study published yesterday in JAMA Ophthalmology. Researchers of this investigation looked at data from a large double-masked, placebo-controlled trial called Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE), jointly conducted in the US and Australia from 2014 to 2018 that tested for efficacy of low-dose aspirin to prolong disability-free survival of older adults. An offshoot of the main study called ASPREE-AMD looked specifically at aspirin’s influence on the course of the disease.

This substudy enrolled a total of 4,993 Australian individuals in ASPREE aged 70 or older without dementia, independence-limiting physical disability, cardiovascular disease or chronic illness limiting five-year survival and with gradable retinal images at baseline. Participants either received 100mg per day of aspirin or a placebo for three years. At trial termination, retinal follow-up data were available for 3,208 patients, with 3,171 being analyzed for AMD incidence and progression. This resulted in a median age of 73.5 years of age and median follow-up tome was 3.1 years. The aspirin group saw a cumulative AMD incidence of 19.4% (195 of 1,004) while the placebo group’s AMD rate was 19.1% (187 of 979). Cumulative progression from early/intermediate AMD to late AMD rates were also similar; the aspirin group rate was 2.3% (14 of 615) and the placebo group was 3.1% (18 of 573).

It should be noted that the ASPREE trial was terminated early and thus captured fewer cases of AMD progression. However, there was also no subgroup of participants for which the effects were different from the main results. That is, aspirin’s impact on AMD was not affected by age, use of alcohol or smoking, sex, BMI, hypertension or use of statins. As well, no evidence suggested that late AMD was more likely to occur in the group randomized to low-dose aspirin.

The study authors relay in their journal article that aspirin was proposed as an intervention for AMD because of its anti-inflammatory property, since inflammation likely plays a role in AMD pathogenesis. These suggestions that aspirin may be beneficial for reducing either AMD risk or progression came from the earlier randomized clinical trials of the Physicians’ Health Study with five-year treatment and the Women’s Health Study with 10-year treatment. However, neither result in these two studies were significant, despite the larger sample sizes and longer aspirin exposure. Both were limited instead by reliance on self-reported AMD status and confirmed by medical reports. Self-reporting is inaccurate, though, especially in early AMD stages.

In the JAMA Ophthalmology article, the authors succinctly summarize that, “overall, these results do not support the suggestion that low-dose daily aspirin prevents the development or progression of AMD.”

Robman LD, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of low-dose aspirin on the course of age-related macular degeneration: a secondary analysis of the ASPREE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. May 23, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |