|

Q:

I have a patient with a severe fungal infection following overnight contact lens wear. The cornea specialist seeing our patient mentioned potentially including newer treatment options of hypochlorous acid, photodynamic therapy or testing to look for mycotoxins. How would these work differently from typical treatment?

Infectious keratitis is the leading cause of unilateral blindness worldwide, and fungal keratitis presents as a challenge in terms of treatment, often necessitating a therapeutic corneal transplant (TPKP) when conventional medical treatment falls short. “The Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (BPEI) regularly handles cases from across south Florida and the Caribbean, constituting approximately 28% of our annual microbiology isolates,” Salomon Merikansky, MD, part of BPEI, explains.

“Fusarium species top the list as the most prevalent causative filamentous fungi, followed by other species like Aspergillus and Curvularia. Among yeast, Candida species is the most prevalent,” he adds.

Typical Treatment

Our current therapy guidelines for filamentous fungal keratitis are based on the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial (MUTT), a multicenter, randomized, double-masked study funded by the National Eye Institute and conducted in Madurai, India. MUTT demonstrated that topical natamycin 5% was more effective than topical voriconazole 1% in treating Fusarium infections. For yeast infections attributed to Candida species, we use topical voriconazole 1% or amphotericin B 0.15%. “It’s important to mention,” Dr. Merikansky relays, “that we strictly avoid the use of topical and/or systemic steroids, instead managing inflammation with topical cyclosporine or topical tacrolimus.”

In cases of advanced corneal fungal disease, the vision and/or globe saving treatment continues to be surgical intervention, such as therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (PK). MUTT showed that patients with clinical signs of hypopyon, infiltrate larger than 6mm or those involving more than two-thirds of the corneal thickness were most likely to have failed medical therapy and require a PK. Dr. Merikansky notes that “since many of the patients that come to our ER have advanced disease, surgical intervention is often required. We have been looking into alternative treatments that try to delay or avoid the need of PK.”

New Options?

Over the past decade, the BPEI has explored rose bengal photodynamic antimicrobial therapy (RB-PDAT) as a potentially emerging treatment for infectious keratitis. This innovative approach uses a photosensitizer (rose bengal) activated by green light to generate singlet oxygen. The method has shown promising results, particularly in early-to-moderate fungal keratitis cases and those caused by Fusarium species. The ongoing Rose Bengal Electromagnetic Activation with Green Light for Infection Reduction study (REAGIR) is a double-masked, randomized clinical trial currently underway and aims to provide critical insights into the future viability of RB-PDAT for fungal keratitis treatment.

|

|

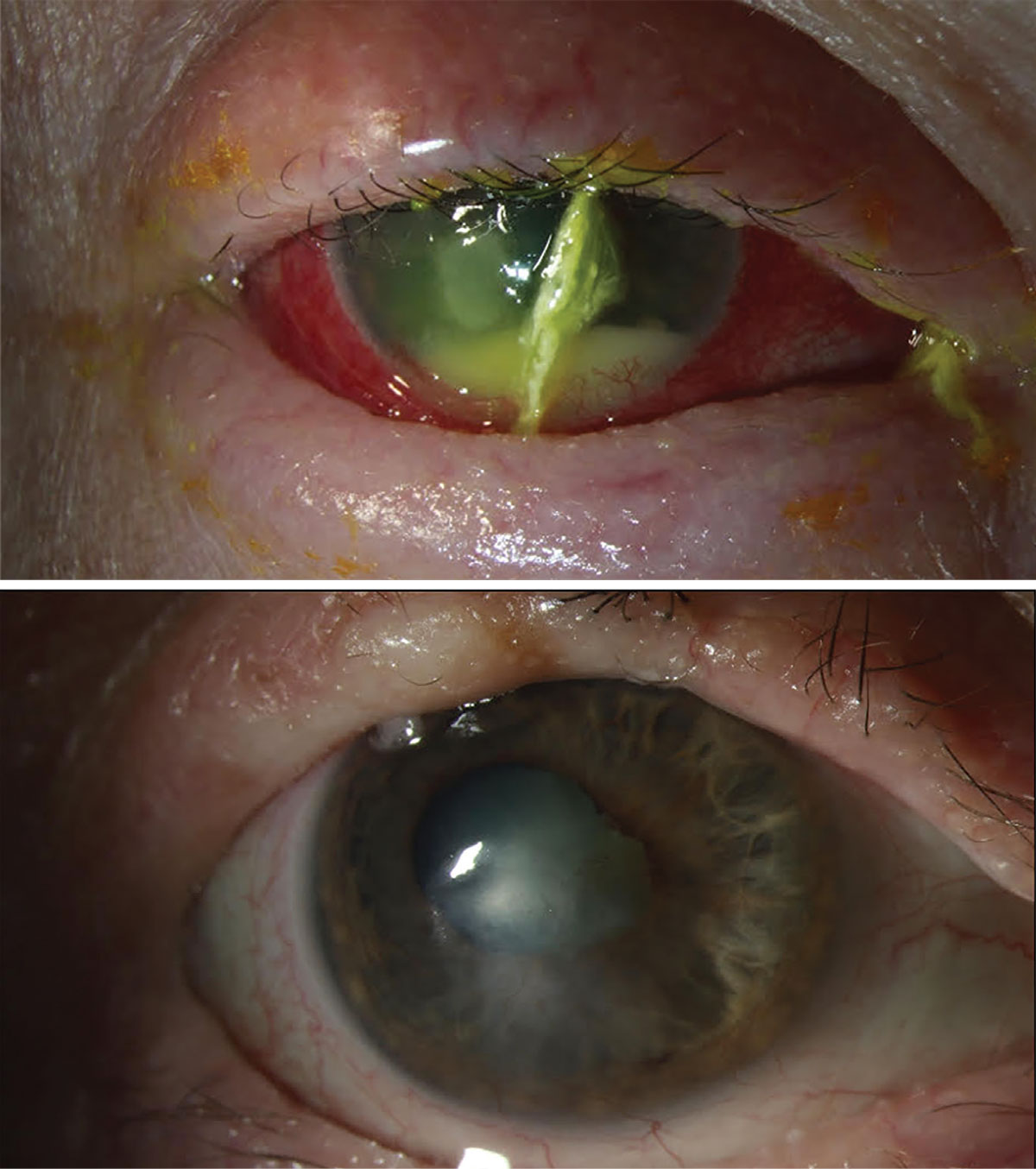

Slit-lamp photograph of a patient with bilateral Curvularia keratitis (top), who was successfully treated with medical therapy and RB-PDAT (bottom). Click image to enlarge. |

“While hypochlorous acid has shown efficacy in treating biofilms on contact lens cases, its direct application as a therapeutic agent remains unexplored in our practice,” Dr. Merikansky says. “However, we do know another key molecule that plays an important role in the pathogenesis of fungal keratitis, that being the work of mycotoxins. They play a significant role in the inflammatory response created by the pathogen and the host’s immune response.”

He adds that “our microbiology laboratory recently published a paper identifying various mycotoxins, where Fumonisin B displayed being a key secondary metabolite of Fusarium species. These toxins contribute to cellular toxicity, potentially leading to keratolysis and perforation.” Understanding the pathophysiology of mycotoxins is crucial, and future research should focus on developing therapies that inhibit mycotoxins to minimize their harmful effects and control the inflammatory response without resorting to steroids.

Where to Start?

These cases are rare, but Dr. Merikansky has a few suggestions for dealing with one if you encounter it. “Prevention and early detection should be our first line of defense. Every eyecare provider should try to excel in educating patients on the correct usage of contact lenses and the potential complications associated with improper use.”

He continues that, in the management of corneal abrasions and/or early keratitis, eyecare providers should be able to identify clinical signs of a possible fungal infection. “For this reason, a high level of suspicion should be made on cases that do not respond to topical broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatments. The use of steroids should always be decided upon judiciously and should only be administered when backed up by microbiological data,” he concludes.

Dr. Merikansky is a research fellow of Guillermo Amescua, MD, who supervised the content for this column.

Dr. Shovlin, a senior optometrist at Northeastern Eye Institute in Scranton, PA, is a fellow and past president of the American Academy of Optometry and a clinical editor of Review of Optometry and Review of Cornea & Contact Lenses. He consults for Kala, Aerie, AbbVie, Novartis, Hubble and Bausch + Lomb and is on the medical advisory panel for Lentechs.