|

When symptoms match signs, the diagnosis of ocular conditions is often straightforward. However, when a treatment is discontinued after the condition has improved or resolved and symptoms return, the practitioner must think of other, less common etiologies and look more closely at the patient themselves. This month’s case involves a poorly compliant contact lens (CL) patient whose symptoms improved with treatment but continued to recur. The misdiagnosis and erroneous treatment resulted in significant permanent loss of vision in one eye.

Case

A contact lens wearer was vacationing in Hawaii, where she went waterskiing while wearing her lenses. When she returned home, she was examined by her regular eye doctor who had fit her for soft CLs a few years before. A review of her prior records had revealed that she had neglected to return for any follow-up visits for about three years. She also had a history of poor CL hygiene and overwore her contact lenses. Her chief complaint at this visit was that, after returning from Hawaii, she developed an itchy, red eye in her right eye.

Best-corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) through her lenses were 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS. The eye doctor did not record very much on the eye chart, including additional history or examination findings. There was no retinal examination. Despite few findings recorded, the eye doctor diagnosed “conjunctivitis” and prescribed tobramycin/dexamethasone eye drops QID OD. He told the patient to discontinue lens wear until her eye was better and to return in one week.

|

|

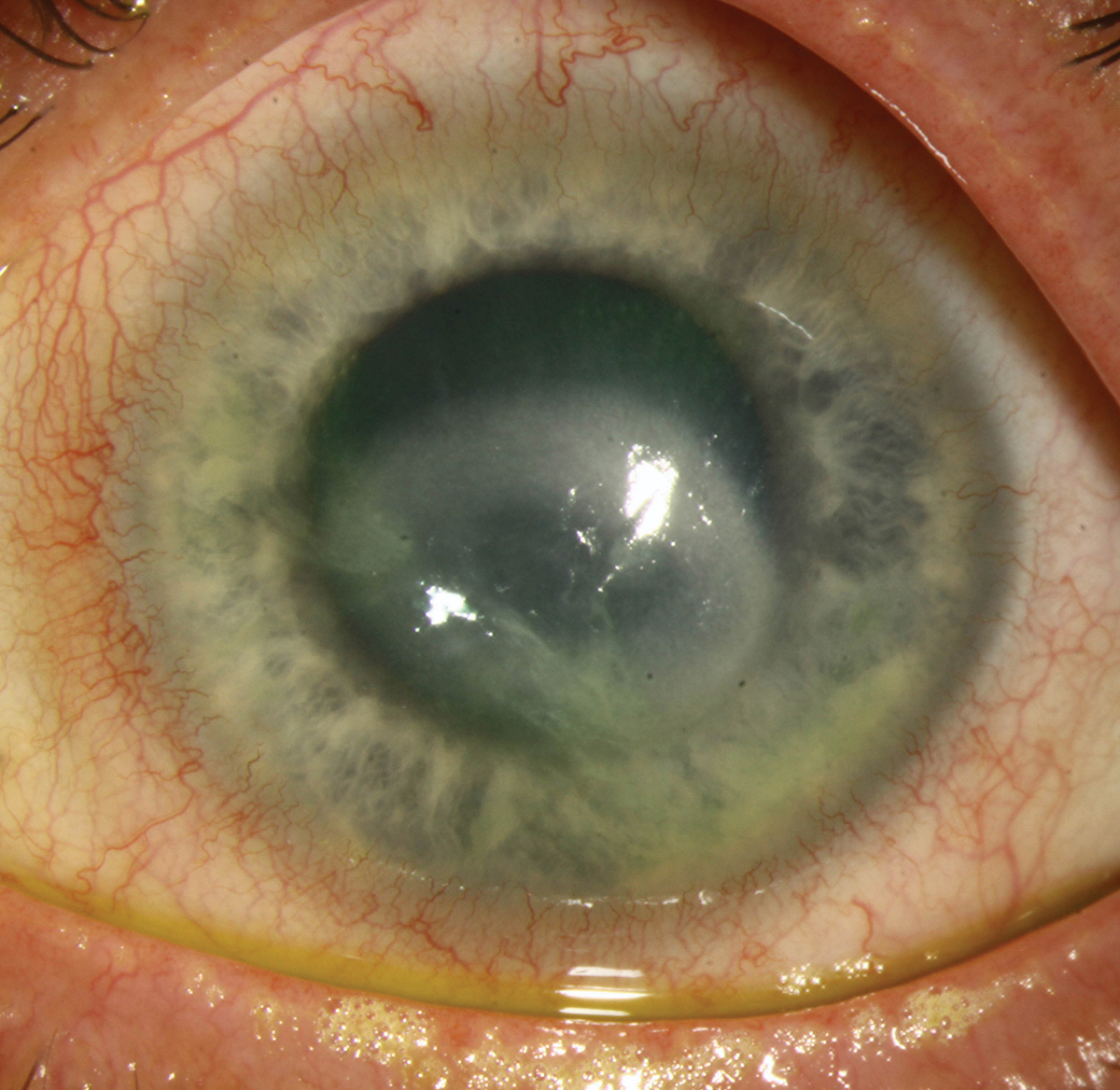

Fig. 1. Early AK with central corneal haze and superficial keratitis in another patient. Photo: University of Iowa. Click image to enlarge. |

Follow-up. The patient returned one week later claiming that she felt “better.” BCVA was still 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS. The eye doctor noted in the record that the BCVA was not as good as it could be. He told her to continue the medication and return in one week. The patient returned in one week, but there was still no change in the visual acuity. However, the symptoms continued to improve. There was no follow-up visit noted after the first two visits. Three months later, the patient went to a second eye doctor, a cornea specialist, saying that her right eye felt “irritated.” The BCVA was 20/25-2 in the right eye. The second eye doctor noted corneal haze and superficial punctate keratitis, the right eye greater than the left eye. The second eye doctor diagnosed “keratitis” and also prescribed tobramycin/dexamethasone eye drops QID OD and artificial tears.

The patient continued using the prescribed eye drops but subsequently developed intense pain in the right eye with significant loss of vision three weeks later. The patient presented to a third eye doctor, another cornea specialist, at a university medical center complaining of intense pain and loss of vision in her right eye. At this visit, the BCVA in the right eye had dropped to light perception. The eye doctor noted the patient had a peripheral corneal infiltrative ring. The third eye doctor suspected Acanthamoeba infection based on the corneal ring, symptoms of intense pain and patient history. A culture subsequently revealed Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK). The patient was treated with anti-amoebic medications, but the condition did not improve.

At this late stage, her only option was penetrating keratoplasty (PK). Repeated corneal grafts failed, and additional grafts at that time were not pursued since it was discovered she also had dense Acanthamoeba infiltration in her sclera as well. Her final BCVA was 20/800.

Malpractice Allegation and Outcome

The patient sued the first two eye doctors for failure to diagnose AK in a timely manner so she could be treated appropriately. In this case, the two eye doctors were deemed to have culpability, and the case was settled to avoid a more costly jury trial. The case was settled for under $500,000.

You Be the Judge

Based upon the information available thus far, what is your opinion?

- Was the first eye doctor culpable for not suspecting Acanthamoeba based on the patient’s history of poor CL compliance and history of waterskiing?

- Was the same doctor culpable because there were no corneal findings on the record and “conjunctivitis” was diagnosed?

- Since the patient improved while on tobramycin/dexamethasone eye drops, is it the standard of care to assume the drops are working?

- Was the second eye doctor culpable since they also failed to consider AK when corneal haze and punctate keratitis was present?

|

|

Fig. 2. Advanced AK with a ring infiltrate and central stromal haze in another patient. Photo: University of Iowa. Click image to enlarge. |

Our Opinion

Acanthamoeba is a free-living protozoa commonly found in soil and water. AK is considered a very rare corneal infection, with an estimated prevalence of one to nine cases per 100,000.1 However, in many developed countries, that number is increasing due to increasing CL wear—a main risk factor, especially with soft lens wear. About 93% of all cases of AK are reported in lens wearers, and infection is usually unilateral.1 Risk factors include poor lens hygiene, overnight wear, wearing lenses during swimming and showering, reuse of disposable contact lenses and the use and efficacy of lens cleaning solutions. The organism exists in an active trophozoite form and an inactive cystic form. The organism is much more difficult to treat when it is present for a long time and exists in cystic form. Topical polyhexamethylene biguanide, an antimicrobial and antiviral medication, and chlorhexidine are effective treatments against the organism but only if initiated early on. The prognosis for visual recovery is excellent, with BCVA as good as 20/25 with early treatment.1

AK, unfortunately, is difficult to diagnose early on. In this case, the patient presented with symptoms of an itchy, red eye and eye irritation. The first eye doctor did not note any significant findings and diagnosed conjunctivitis. When the patient went to the second eye doctor, she only complained of eye irritation. The corneal haze and punctate keratitis that was seen at that visit could have been a sign of an early AK infection, but just “keratitis” was diagnosed likely based on the lack of symptoms and rarity of AK (Figure 1).

Symptoms of advanced AK include photophobia and pain disproportionate to the corneal findings, symptoms the patient did not report. The patient’s symptoms waxed and waned with periodic improvement, since the eye doctors she saw prescribed antibiotic/steroid eye drops and the patient continued to use them as it improved her symptoms.

Steroids can promote the transition of cysts to active trophozoites, hence the steroid eye drops only made the condition worse. Also, the patient did not follow-up for a few months after her second visit with the first eye doctor, presumably because the symptoms resolved with use of the steroid eye drops. The patient had a history of poor follow-up compliance with her CLs, missing check-ups for years and likely reusing her disposable lenses. She also had a history of waterskiing while wearing her lenses. Hence, one of us (SB) opined that, since the first eye doctor did not record any findings but only a diagnosis of conjunctivitis, it is difficult to say what was seen during the examination, possibly just a red eye. The second eye doctor noted corneal haze and punctate keratitis; again, it is difficult to prove the patient had AK since she only complained of eye irritation. Therefore, it is questionable whether the two practitioners are culpable since the standard of care would likely not be to suspect AK based on the symptoms, the findings and the rarity of AK, as well as the fact that the patient appeared to be improving.

By the time she was diagnosed, the only treatment was a corneal graft, but unfortunately, multiple grafts failed. The prognosis was poor, and future treatment was not advised because additional testing revealed the Acanthamoeba had spread into her scleral tissue. This is an unfortunate series of events, but the two eye doctors had no reason to suspect AK. Once the patient developed intense pain and a ring infiltrate, AK became more suspect, but by then it was too late for treatment to be effective.

Takeaways

When should an Acanthamoeba infection be suspected? Unfortunately, once the peripheral corneal ring is seen (Figure 2) and the patient is photophobic and in intense pain, treatment may be too late and a PK may be the only option. However, if a patient initially “feels better” while on an antibiotic/steroid combination but then symptoms return and keep returning once the medications have been discontinued and there is a history of being in the water while wearing contact lenses in a patient as well as a history of poor compliance with lens wear and follow-up, there may be red flags to consider an early AK infection. It might be prudent in these cases to consider getting or referring for a culture even if it turns out not to be AK.

| NOTE: This article is one of a series based on actual lawsuits in which the author served as an expert witness or rendered an expert opinion. These cases are factual, but some details have been altered to preserve confidentiality. The article represents the authors’ opinion of acceptable standards of care and do not give legal or medical advice. Laws, standards and the outcome of cases can vary from place to place. Others’ opinions may differ; we welcome yours. |

Dr. Sherman is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY State College of Optometry and editor-in-chief of Retina Revealed at www.retinarevealed.com. During his 52 years at SUNY, Dr. Sherman has published about 750 various manuscripts. He has also served as an expert witness in 400 malpractice cases, approximately equally split between plaintiff and defendant. Dr. Sherman has received support for Retina Revealed from Carl Zeiss Meditec, MacuHealth and Konan.

Dr. Bass is a Distinguished Teaching Professor at the SUNY College of Optometry and is an attending in the Retina Clinic of the University Eye Center. She has served as an expert witness in a significant number of malpractice cases, the majority in support of the defendant. She serves as a consultant for ProQR Therapeutics.

1. Varacalli G, Di Zazzo A, Mori T, et al. Challenges in Acanthamoeba keratitis: a review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):942. |