|

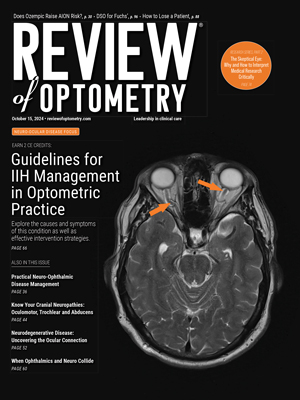

A 60-year-old African American woman with no past ocular history presented to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute emergency department with blurry vision in the left eye for two weeks. The exam was notable for visual acuity of 20/20 in the right eye and counting fingers in the left. Intraocular pressures measured 13mm Hg and 15mm Hg in the right and left eyes, respectively. Slit-lamp exam was unremarkable with a clear cornea and no inflammatory cells or flare in either eye. Posterior segment exam of the left eye revealed epiretinal membrane, pseudohole and blurred inferior and superior disc margins; the posterior segment exam was unremarkable in the right eye. The pseudohole and epiretinal membrane in the left eye were not suspected to be the main cause for the severe decrease in vision due to their mild appearance and maintenance of the outer retinal anatomy. In the setting of poor vision and disc edema, an MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast was obtained. The MRI revealed bilateral anterior clinoidal lesions with optic nerve sheath involvement bilaterally, worse on the left side than the right (Figure 1).

|

Fig. 1. Nodular mass-like extra-axial enhancement in the bilateral middle cranial fossa, centered about the clinoid processes. There is also focal enhancement of the left optic disc. Click image to enlarge. |

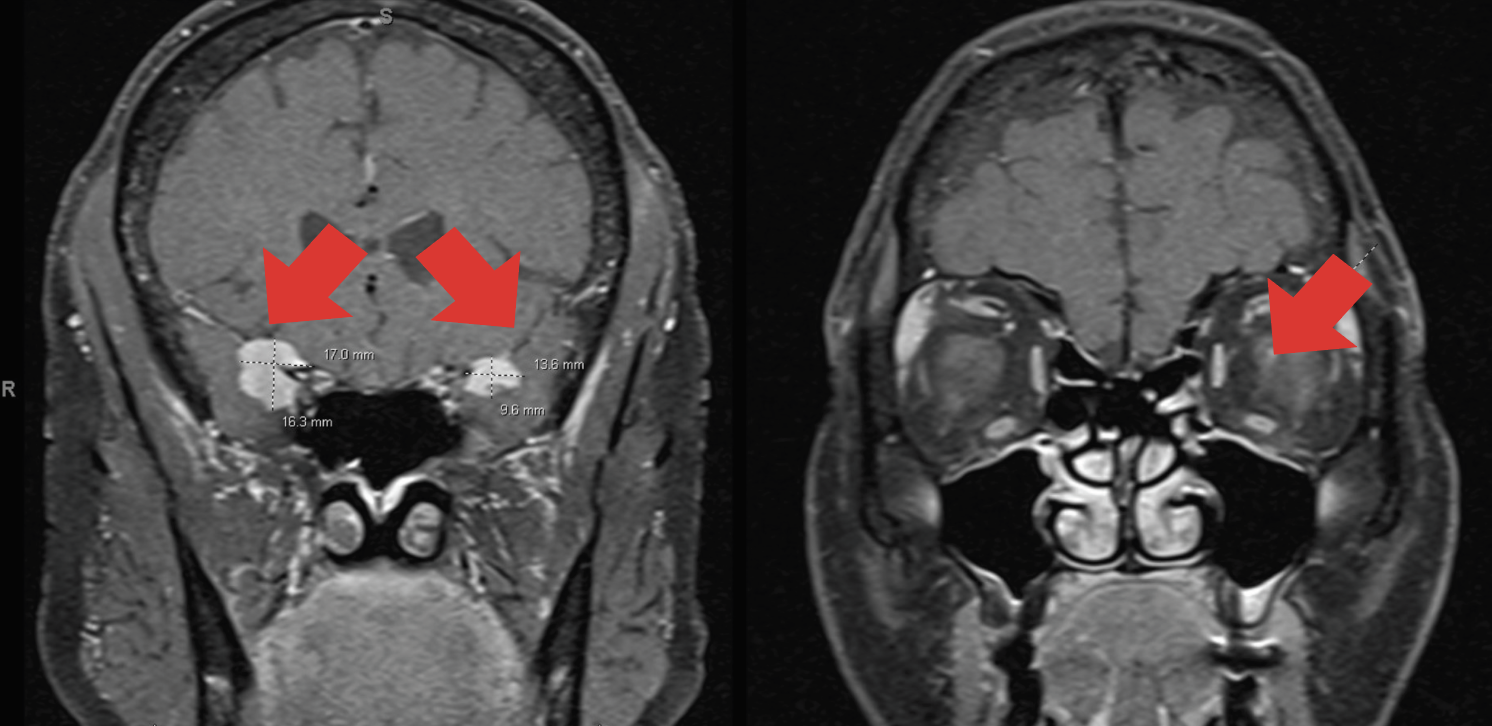

Two days after initial presentation, the patient followed up in our neuro-ophthalmology clinic with a new onset intermediate uveitis in the left eye. Clinical exam showed keratic precipitates, 3+ anterior chamber reaction, 3+ vitreous cell with 1+ flare and grade one disc edema OS (Figures 2 and 3). Exam was stable in the right eye. A comprehensive review of systems revealed that the patient experienced joint pain, scattered nodular skin lesions across her body, hypoesthesia in the distal extremities and neck pain. She was transferred to an inpatient clinic for a further systemic workup given the high suspicion for sarcoidosis. We recommended an extensive lab workup including lab studies (ACE, RPR, FTA, ANCA, CBC, FTA, IgG4), chest CT with contrast and a spinal tap. The patient was advised to start prednisolone acetate 1.0% drops four times per day OS while admitted.

|

Fig. 2. In these fundus photos, the right eye (left image) appears unremarkable, while the left eye (right image) shows a hazy view with disc edema and an epiretinal membrane. Click image to enlarge. |

The Culprit

Sarcoidosis is a chronic multisystem disease and a common cause of ocular inflammation.1 It is characterized by the formation of noncaseating granulomas in affected organs, most commonly the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, heart and eyes.2 Ocular sarcoidosis can be isolated to the eye or associated with other organ involvement. Ocular involvement ranges from 13% to 79% in patients with systemic sarcoidosis, and only 2% of cases have ocular complaints at initial presentation.3-6 Sarcoidosis affects all ethnic groups with the highest prevalence in northern European countries, where the condition affects 40 per 100,000 people.7 In the US, African Americans are 10 times more likely to develop ocular involvement compared with Caucasians.1 Onset occurs between the ages of 20 and 50 years with a slight female predominance.7

|

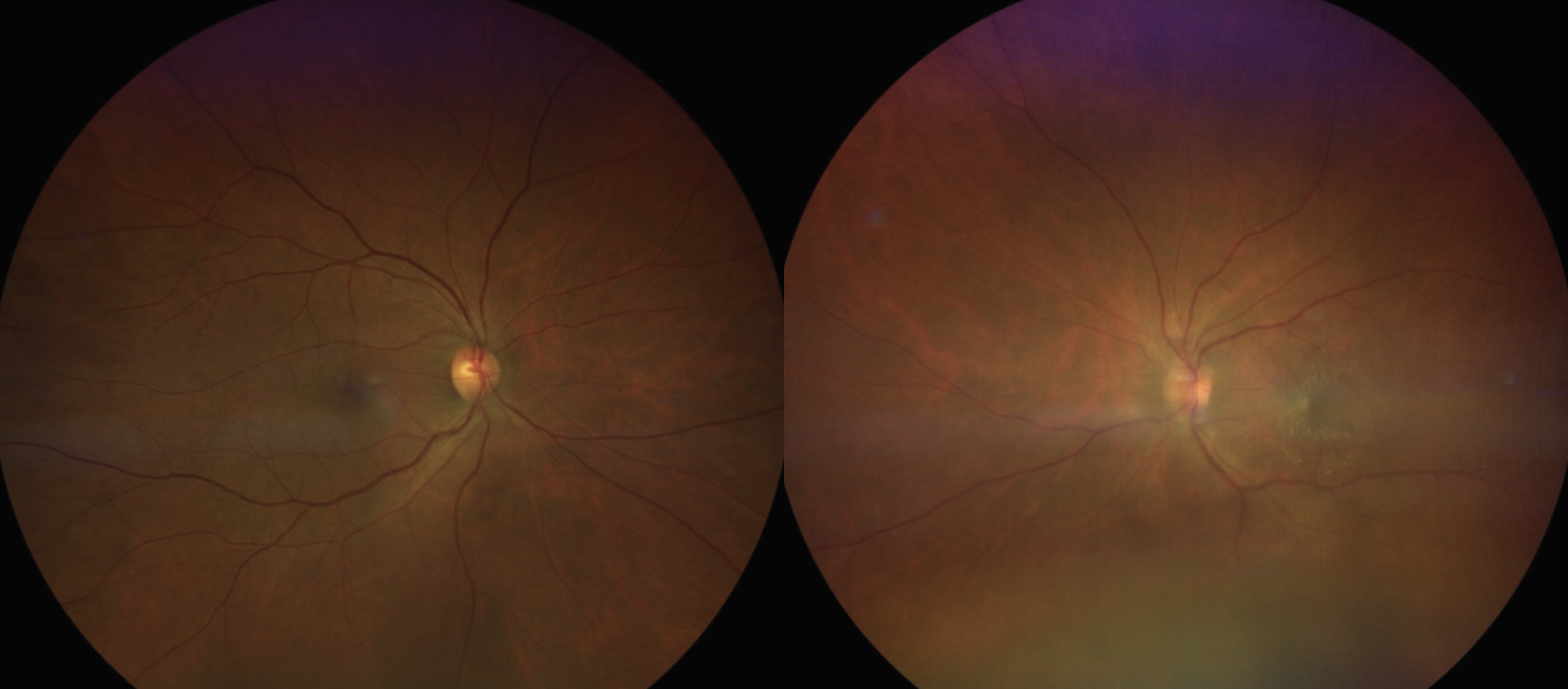

| Fig. 3. An OCT scan of the left eye reveals notable vitreous inflammatory cells, an epiretinal membrane and a pseudohole. Click image to enlarge. |

Ocular Manifestations

Sarcoidosis can affect any ocular tissue and adnexa. Approximately 30% to 70% of cases initially present with unilateral or bilateral uveitis.8 Anterior uveitis manifests with mutton-fat keratic precipitates (especially in an Arlt triangle), Koeppe and Busacca iris nodules and anterior and posterior synechiae.6,9 In intermediate uveitis, inflammatory aggregates organize as a clump of snowballs or in a linear strand referred to as a “string of pearls.”6,9 Posterior involvement occurs in 20% of patients with ocular sarcoidosis.2 Yellow or white nodular granulomatous lesions may present in the optic nerve, retina or choroid. Mid-peripheral periphlebitis is characteristic of ocular sarcoidosis.10 In severe cases, small, yellowish-white nodular granulomas accumulate along retinal venules, classically termed “candle-wax drippings.”6-9

Even though uveitis is predominantly associated with sarcoidosis, other ocular manifestations include scleritis, conjunctival granulomas, acute follicular conjunctivitis, orbital inflammation and lacrimal gland inflammation.11 Branch or central retinal vein occlusions together with peripheral retinal nonperfusion can lead to neovascularization and vitreous hemorrhages.2,6 Orbital findings include palpable masses, ptosis, ophthalmoplegia and proptosis often resembling thyroid ophthalmopathy.2,6 Vision-threatening complications of chronic inflammation include band keratopathy, cataracts, glaucoma, cystoid macular edema and optic nerve edema.

Diagnosis and Treatment

For suspected ocular sarcoidosis the traditional approach is to obtain serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and lysozyme levels. Elevated serum ACE is 73% sensitive, but when used in conjunction with whole-body gallium scanning, the sensitivity increases to 100%.12 Serum lysozyme, on the other hand, has a 60% sensitivity for sarcoid uveitis.13 ACE and lysozyme levels represent the granuloma burden of the body, and if the disease is isolated to the eye, these levels might be read as normal. A chest X-ray is a great screening tool for sarcoidosis, but if the reading is normal and suspicion of sarcoidosis is high, a CT scan of the chest should be considered. While more invasive, the gold standard for diagnosis is tissue biopsy of accessible affected lesions (lung, lymph nodes, skin lesions, lacrimal gland or conjunctiva).

In 2017, uveitis specialists wrote the criteria for the diagnosis of intraocular sarcoidosis, referred to as the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis.14 Diagnostic criteria include seven ocular manifestations and eight systemic investigation results found in ocular sarcoidosis. The diagnostic grading ranges from “definitive” (tissue biopsy) to “presumed” (typical ocular findings with bilateral hilar adenopathy) to “possible” disease (supporting ancillary evidence).14

Treatment options vary depending on the severity and chronicity of the disease. Topical, periocular or systemic corticosteroids are considered first-line treatment for ocular sarcoidosis. Topical corticosteroids paired with cycloplegics are recommended for anterior uveitic disease. Intravitreal, periorbital or implanted corticosteroids are reserved for posterior segment involvement. Systemic corticosteroids are considered in chronic cases, systemic sarcoidosis or in those who respond poorly to topical or regional therapy.14 Immunosuppressive therapy or biologics are effective steroid-sparing agents in patients who require long-term management or are intolerant to systemic steroids.6,9 Laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy or anti-VEGF are administered for retinal neovascularization.6,9 Treatment options to consider in advanced cases include cataract surgery, vitrectomy and/or a glaucoma device implant.2,6 Establishing care with an internist, rheumatologist or pulmonologist is essential for systemic management, as these patients often require long-term management.9 Visual prognosis depends on the severity and chronicity of the condition, as well as whether the patient receives appropriate treatment. Patients should be closely monitored by a uveitis specialist and, if necessary, a neuro-ophthalmologist or retina specialist.

|

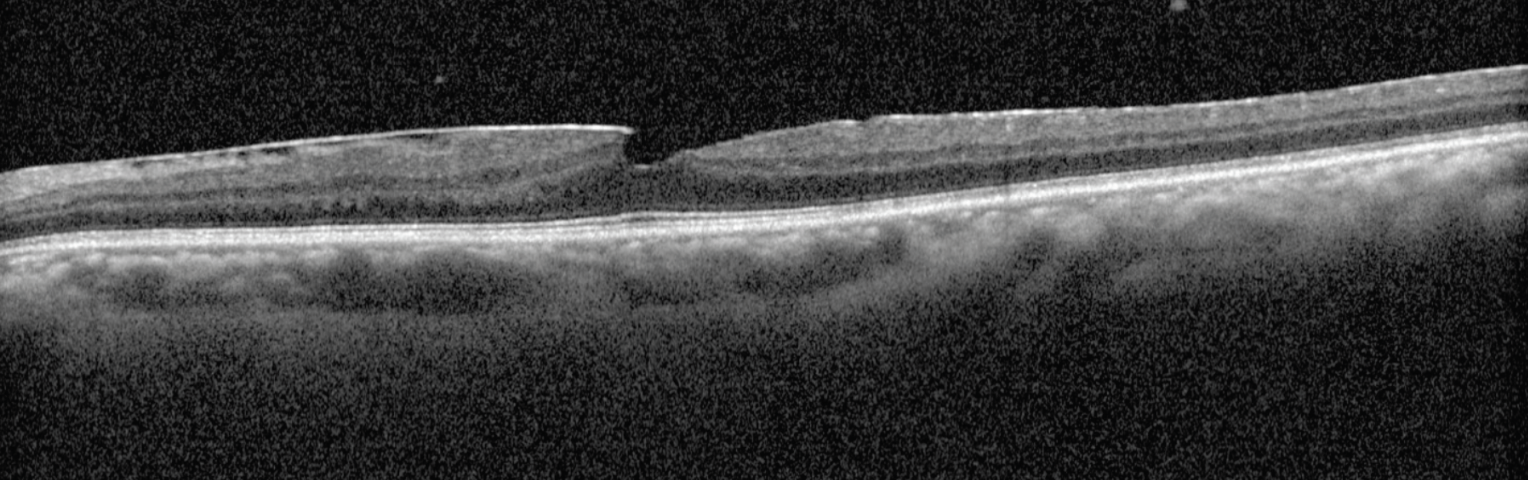

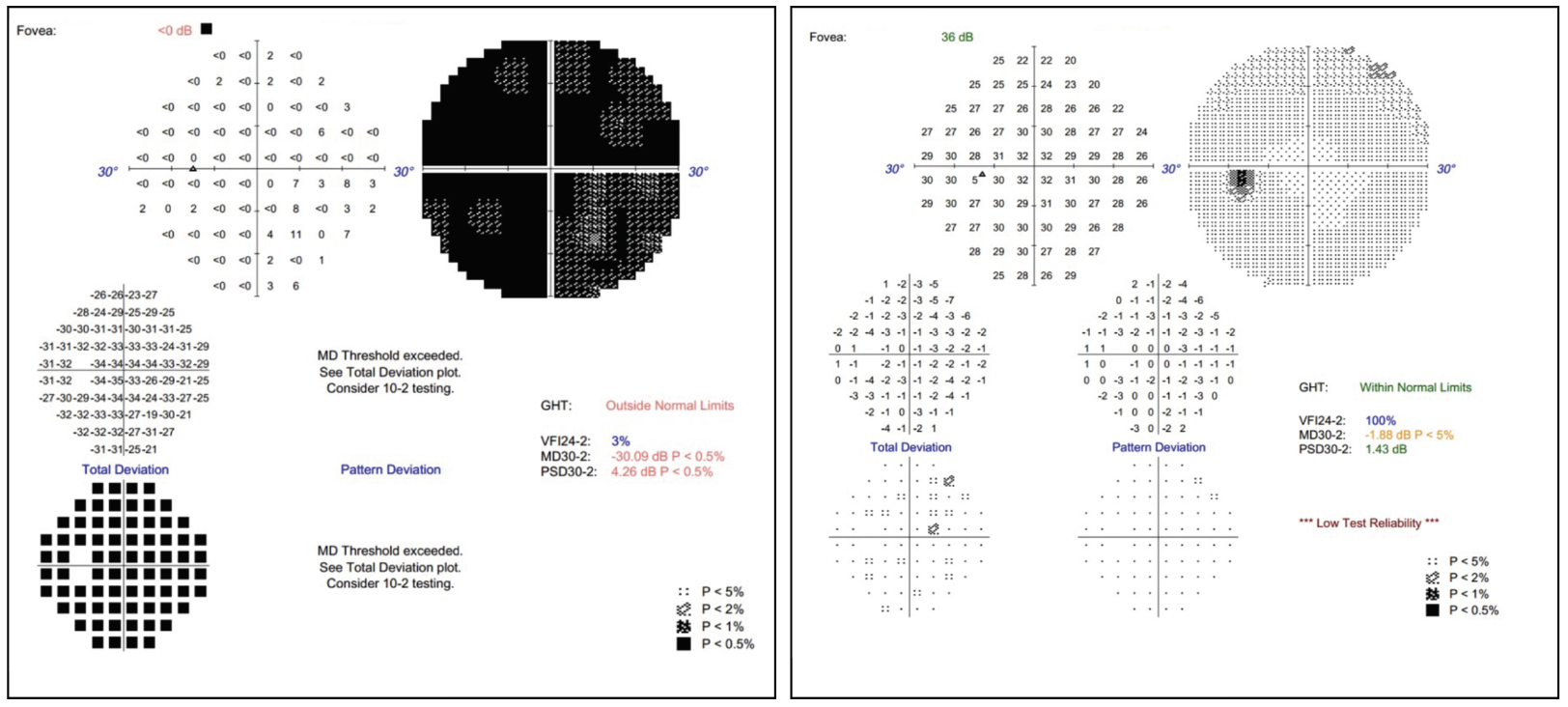

| Fig. 4. Visual field of the left eye at initial presentation (left) vs. post-systemic treatment (right). Click image to enlarge. |

Back to Our Patient

The patient’s chest CT showed multiple lung nodules and hilar lymphadenopathy. A lung biopsy was performed, and the pathology revealed non-caseating granulomas, confirming a diagnosis of sarcoidosis with ocular involvement. The patient started systemic therapy (mycophenolic acid and oral prednisone). The patient is currently doing well on systemic treatment, and her vision improved from counting fingers to 20/20 OS (Figure 4) while the right eye has remained stable. She established care with neurology and rheumatology.

It is important for optometrists to identify the ocular manifestations of sarcoidosis, as we might be the first to encounter its initial presentation. Timely treatment, thorough lab workup and proper referrals can help preserve vision and enhance the quality of life for these patients.

Dr. Bozung currently practices at Bascom Palmer where she primarily sees patients in the hospital's 24/7 ophthalmic emergency department. She also serves as the optometry residency program coordinator. Dr. Bozung is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a member of the Florida and American Optometric Associations. She is a founding board member of Young OD Connect and serves on the editorial board for Review of Optometry. She has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Pengo received her Doctor of Optometry degree at New England College of Optometry in Boston. She is currently an ocular disease resident at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. She has no financial disclosures.

|

1. Bodaghi B, Touitou V, Fardeau C, Chapelon C, LeHoang P. Ocular sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2012;41(6 Pt 2):e349-54. 2. EyeWiki. Sarcoid uveitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published September 19, 2023. eyewiki.aao.org/sarcoid_uveitis. Accessed June 19, 2024. 3. Rothova A. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:110-6. 4. Atmaca LS, Atmaca-Sonmez P, Idil A, et al. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:91-4. 5. Ohara K, Okubo A, Sasaki H, et al. Intraocular manifestations of systemic sarcoidosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1992;36:452-7. 6. Friedman NJ, Kaiser PK, Pineda R. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. Elsevier. 2021;703-4. 7. Basic and clinical science course, section 09: uveitis and intraocular inflammation. Am Acad Ophthalmol. 2017;132-9. 8. Matsou A, Tsaousis KT. Management of chronic ocular sarcoidosis: challenges and solutions. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:519-32. 9. Gervasio KA, Peck TJ, Fathy CA, Sivalingam MD, Friedberg MA, Rapuano CJ. The Wills Eye Manual: office and emergency room diagnosis and treatment of eye disease. Wolters Kluwer. 2022. 10. Simakurthy S, Tripathy K. Ocular sarcoidosis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 25, 2023. 11. Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):669-83. 12. Nosal A, Schleissner LA, Mishkin FS, Lieberman J. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme and gallium scan in noninvasive evaluation of sarcoidosis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1979;90(3): 328-3. 13. Baarsma GS, La Hey E, Glasius E, de Vries J, Kijlstra A. The predictive value of serum angiotensin converting enzyme and lysozyme levels in the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;15;104(3):211-7. 14. Mochizuki M, Smith JR, Takase H, Kaburaki T, Acharya NR, Rao NA; International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis Study Group. Revised criteria of International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(10):1418-22. |