|

A 43-year-old woman presented to the ophthalmic emergency department with complaints of intermittent blurred vision and colorful spots in her left eye for the past five weeks, accompanied by gradually improving generalized headaches. The patient reported no eye pain or double vision. She had been diagnosed with ocular migraine two weeks prior; otherwise, her medical history was unremarkable.

On examination, her vision pinholed to 20/20 OD and 20/20-2 OS. Her intraocular pressures were 13mm Hg OD and 11mm Hg OS. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect (APD) in either eye. Extraocular motilities were full without pain, confrontation visual fields were intact and there was no proptosis. The anterior and posterior segments were unremarkable without evidence of glaucomatous cupping or optic disc edema.

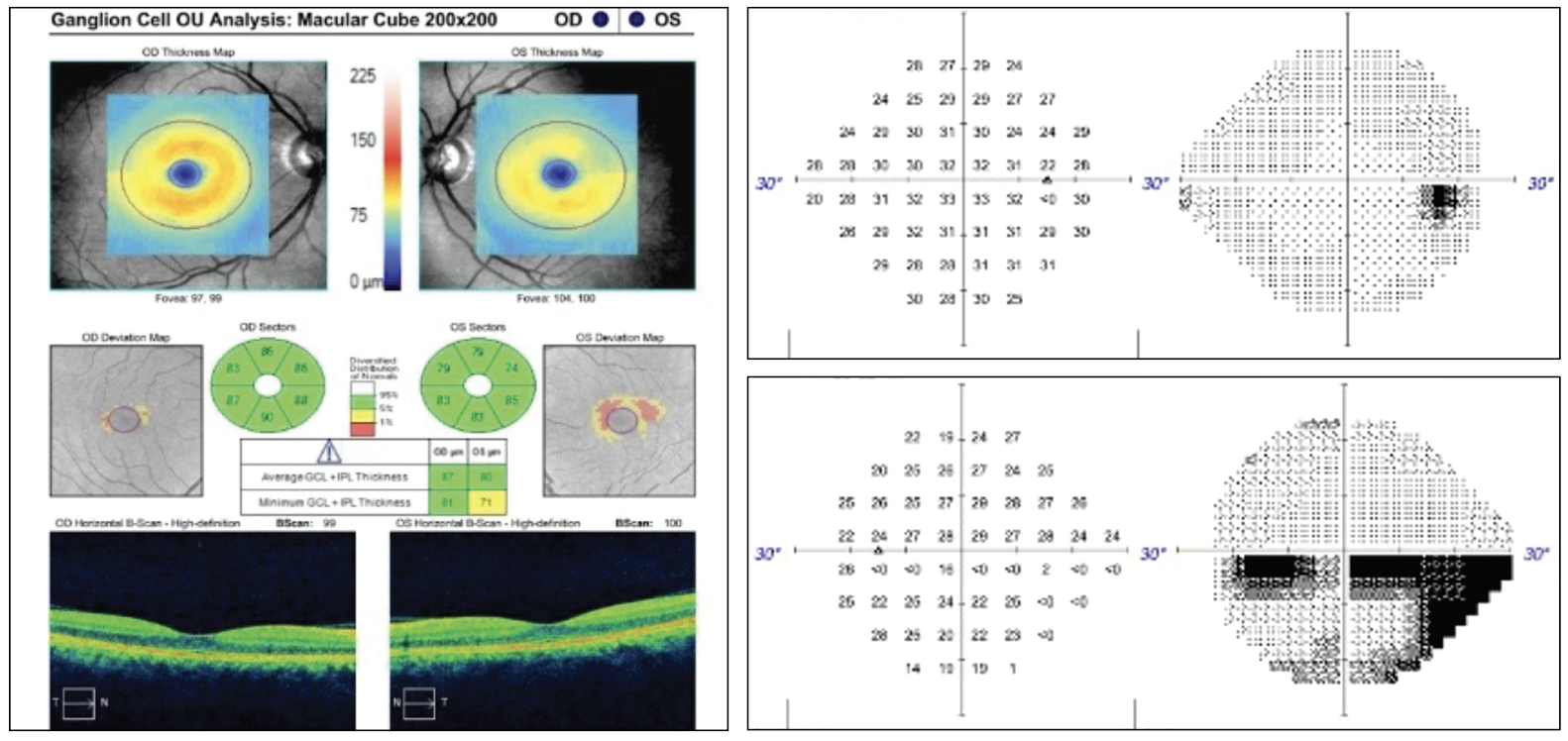

Given an unrevealing exam thus far, the patient was asked to describe her visual symptoms in greater detail. She then reported a stationary hazy, horizontal dark line extending through the center of her vision with details of images below the line appearing darker and less clear. Given this information, further testing was completed. She identified 11/11 color plates in the right eye and 9/11 in the left, noted an estimated 40% red cap desaturation in the left eye vs. the right and had an inferior visual field defect on formal perimetry testing. Optical coherence tomography corroborated the visual field results.

|

Fig 1. OCT ganglion cell analysis of the left eye indicated superior temporal thinning. The 24-2 visual field of the right eye was largely unremarkable but the left eye demonstrated an incomplete inferior altitudinal defect. Click image to enlarge. |

Differentials

The first differential that often comes to mind for patients with an altitudinal visual field defect is non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION). This condition typically presents with decreased vision, dyschromatopsia, an APD, optic disc edema with splinter hemorrhages and a visual field defect. The unaffected fellow eye will often exhibit a small optic disc with a small cup-to-disc ratio. NAION is presumed to result from insufficient blood flow to the retrolaminar portion of the optic nerve, which is supplied by the short posterior ciliary arteries. Common confounding variables include diabetes, hypertension and certain medications. This diagnosis is typically made when characteristic clinical signs are present and other conditions have been excluded. In atypical cases, ordering infectious or inflammatory labs and/or neuroimaging may be prudent. In elderly populations, it is recommended to complete a comprehensive review of systems and consider ordering laboratory testing such as a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein to stratify risk of giant cell arteritis.1

Our patient showed no signs of current or previous optic disc edema or pallor, making NAION less likely. In our patient’s age group (40s), a new onset inferior altitudinal visual field defect could also be associated with retrobulbar optic neuritis. Typically, optic neuritis occurs in young to middle-aged patients with decreased vision, pain associated with eye movement, a relative APD, dyschromatopsia and a visual field defect.² Although the most prevalent visual field defect seen in optic neuritis is diffuse depression with central or cecocentral scotomas, there have been documented cases of optic neuritis initially presenting with altitudinal defects; interestingly, this includes some that were secondary to neuromyelitis optica.2 When suspecting optic neuritis, an MRI of the brain and orbits with gadolinium contrast is warranted.

|

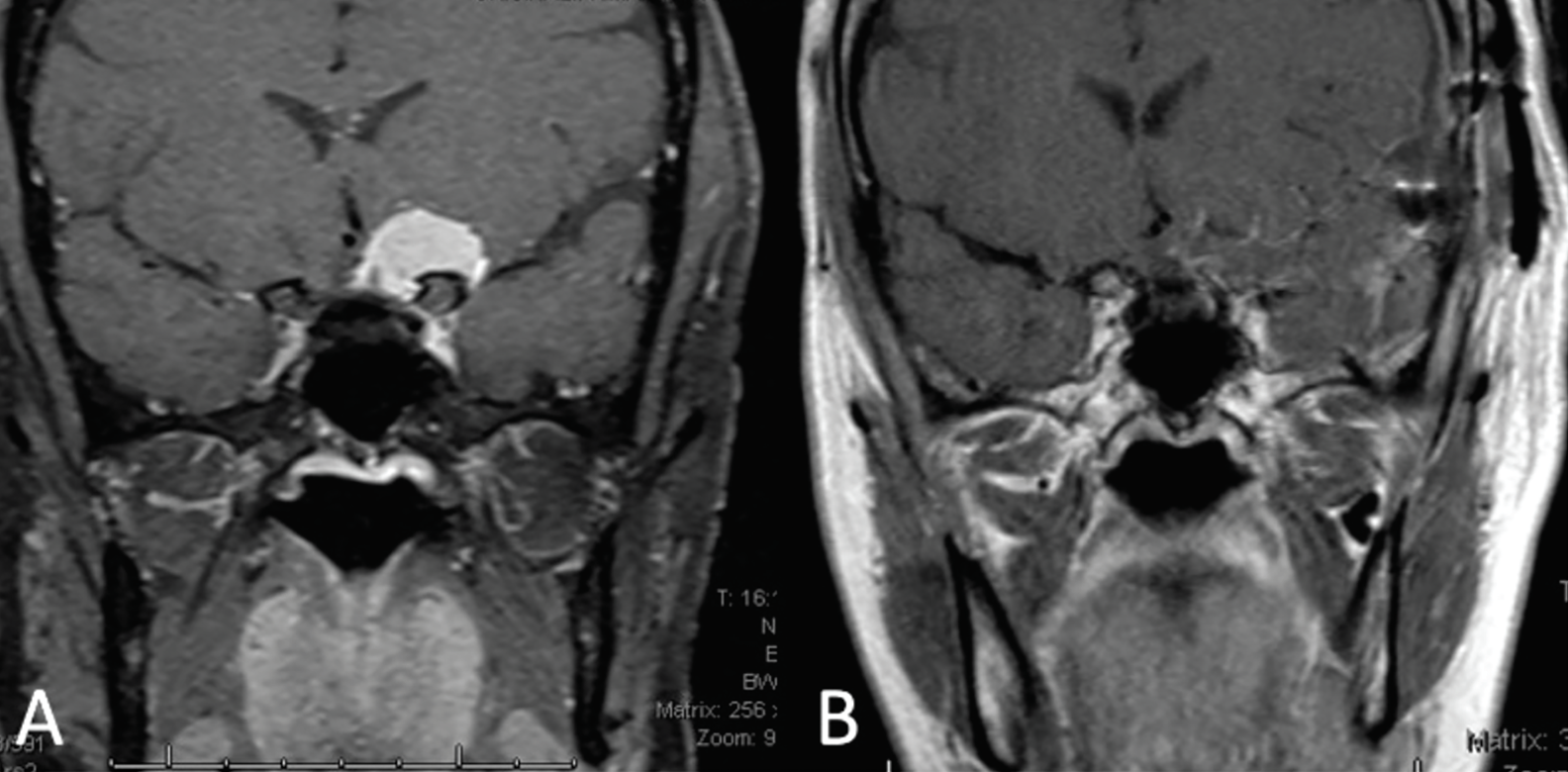

| Fig 2. (A) Coronal MRI depicts an approximately 2cm paraclinoid meningioma exerting its mass effect on the left half of the optic chiasm and the prechiasmic optic nerve. (B) Coronal MRI taken two weeks post-craniotomy and resection of the meningioma. Click image to enlarge. |

When a patient presents with visual field defects but no identifiable ocular cause, compressive lesions must be ruled out. These lesions may be secondary to numerous etiologies, and they are associated with various signs and symptoms. Compression of fibers along the visual pathway can occur due to direct pressure from a mass lesion or indirect compression caused by inflammation or hemorrhage as a consequence of the lesion. Depending on the lesion’s location, the patient can experience several non-specific symptoms such as headache, a relative APD, peripheral neuropathies and difficulty performing daily tasks.3 With a unilateral inferior visual field defect, our patient raises suspicion for a lesion along the superior optic nerve between the globe and the optic chiasm. Common lesions to compress the intraorbital and intracranial optic nerve include, but are not limited to, cavernous hemangiomas, meningiomas and optic nerve gliomas. A prompt MRI with gadolinium contrast is critical to rule out these types of lesions, particularly with acute symptoms.

Further Imaging

Given our patient’s clinical vignette, neuroimaging was indicated to assess for optic neuritis or a compressive lesion. MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast revealed a ~2cm round mass arising from the left anterior clinoid process and extending medially over the tuberculum sella, exerting its mass effect on the left half of the optic chiasm and prechiasmatic segment of the left optic nerve. The lesion was reported to be consistent with a paraclinoid meningioma.

Given evidence of optic nerve compression, the patient was seen emergently by neurosurgery. The following day, she underwent a left pterional craniotomy and resection of the tumor without complication. Pathology confirmed the mass to be a grade I meningioma based on WHO guidelines. At the patient’s two-week follow-up, she reported improvement of vision in her left eye with residual headaches but no other symptoms. She had resumed normal daily activities.

The Culprit

Meningiomas are the most common primary intraorbital tumor. While usually classified as benign, these tumors can still lead to serious consequences due to their effect on other structures of the brain. They often manifest with symptoms such as headaches, neurological deficits and seizures with insidious onset due to their slow-growing nature.4

Clinoid meningioma arises from the dural tissue surrounding the anterior clinoid process. It has been reported that about 60% of clinoid meningiomas induce visual symptoms by encroaching on areas such as the optic canal due to their close proximity. These tumors can disrupt vision through these three mechanisms: direct compression of the optic nerve, small-vessel compromise leading to ischemia, and demyelination.5

The gold standard for management of these lesions is total resection, aiming to decompress the optic nerve, relieve ischemia and prevent recurrences. Although complete resection is not always feasible, new microsurgical techniques have increased total resection rates to just under 90%, up from the previous rate of 55%. Despite a low recurrence rate, recurrent or residual lesions tend to be more aggressive and are managed with Gamma Knife radiosurgery due to higher risk associated with repeat resection.5

Clinical Pearls

This case emphasizes several important points. First, it may be helpful to differentiate between positive and negative visual phenomena when patients report “seeing spots.” A positive visual phenomenon (seeing lights or images) will typically result from disruption of visual input such as migraine auras, retinal traction causing flashes or, in some cases, even hallucinations. Negative visual phenomena (seeing dark areas), on the other hand, are more commonly caused by lesions or ischemic insult along the visual pathway inhibiting visual signals to the brain.6 In such cases, an in-office visual field test is essential, as it can help localize a suspected lesion.

This case also illustrates the difficulty some patients may face in describing certain visual phenomena and the importance of having them describe their symptoms in detail. Even a prominent inferior altitudinal defect might be perceived by the patient as their vision “being off” until proper testing and history are completed. As primary eyecare providers, our exam chair may be the initial setting where these symptoms come to light. Requesting additional details and thorough testing of pupils, color perception and visual fields can play a vital role in saving a patient’s vision—or possibly even their life.

Dr. Calvert earned his Doctor of Optometry degree from The Ohio State University College of Optometry and completed a residency in ocular disease at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, FL. He recently launched his private practice career in Bowling Green, KY.

Dr. Bozung currently practices at Bascom Palmer where she primarily sees patients in the hospital's 24/7 ophthalmic emergency department. She also serves as the optometry residency program coordinator. Dr. Bozung is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a member of the Florida and American Optometric Associations. She is a founding board member of Young OD Connect and serves on the editorial board for Review of Optometry. She has no financial interests to disclose.

|

1. Kerr NM, Chew SS, Danesh-Meyer HV. Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: a review and update. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(8):994-1000. 2. Onder H, Khasiyev F, Karabudak R. Optic neuritis presenting with altitudinal visual field defect in a neuromyelitis optica patient. J Neurol Res. 2018;7(6):112-4. 3. Takahashi M, Goseki T, Ishikawa H, Hiroyasu G, Hirasawa K, Shoji N. Compressive lesions of the optic chiasm: subjective symptoms and visual field diagnostic criteria. Neuroophthalmology. 2018;42(6):343-8. 4. Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T, Horowitz PM, James CD, Lukas RV. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol. 2018;14(21):2161-77. 5. Pamir MN, Özduman K. Clinoidal meningiomas. Handb Clin Neurol. 2020;170:25-35. 6. Barral E, Martins Silva E, García-Azorín D, Viana M, Puledda F. Differential diagnosis of visual phenomena associated with migraine: spotlight on aura and visual snow syndrome. Diagnostics. 2023;13(2):252. |