|

A 53-year-old man presented with three days of pain and redness in the left eye. He denied loss of vision and reported he had undergone uncomplicated cataract surgery at an outside facility one week prior to presentation. The right eye had also undergone cataract surgery three weeks prior to presentation and was asymptomatic. His past medical history was significant for alcoholic cirrhosis and hypertension.

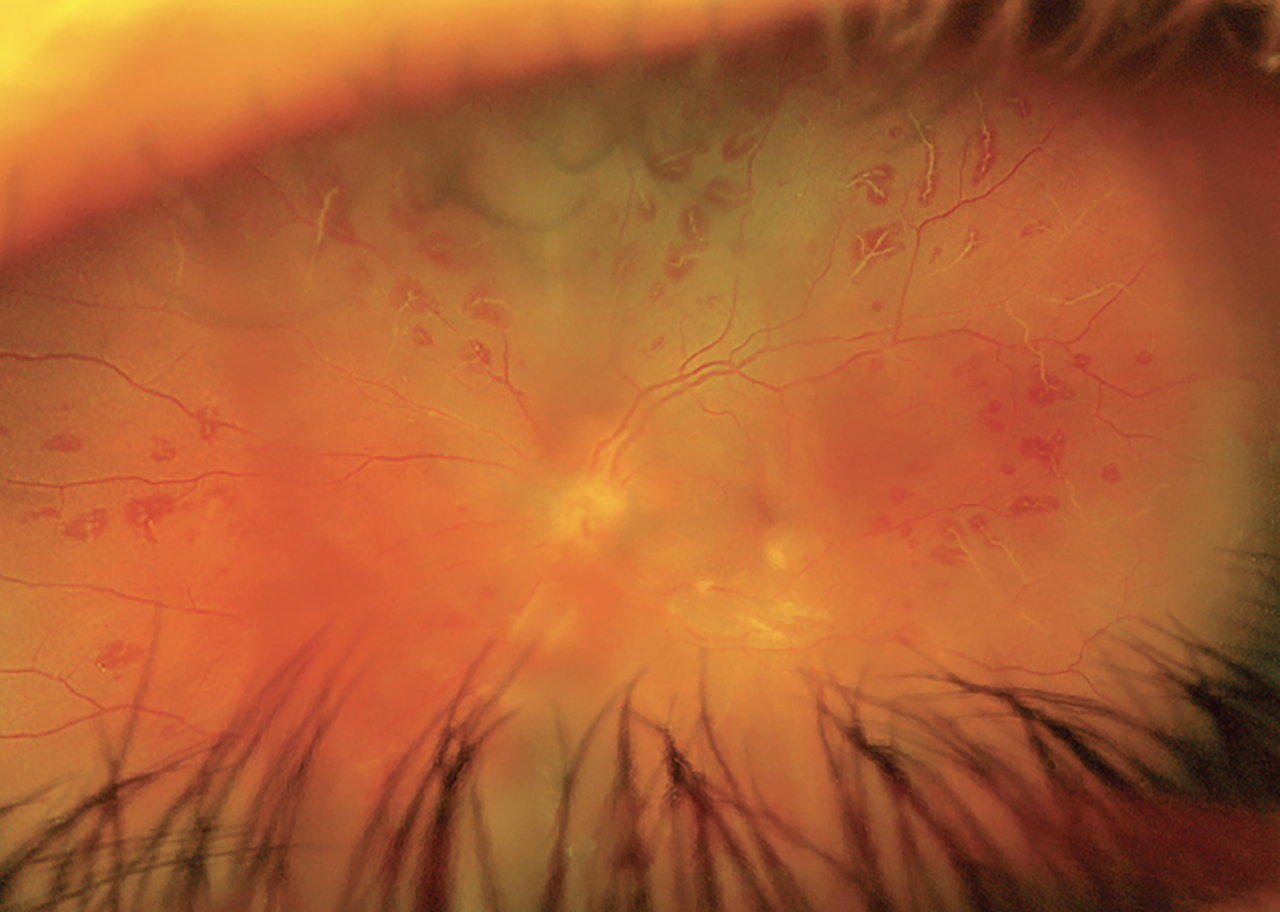

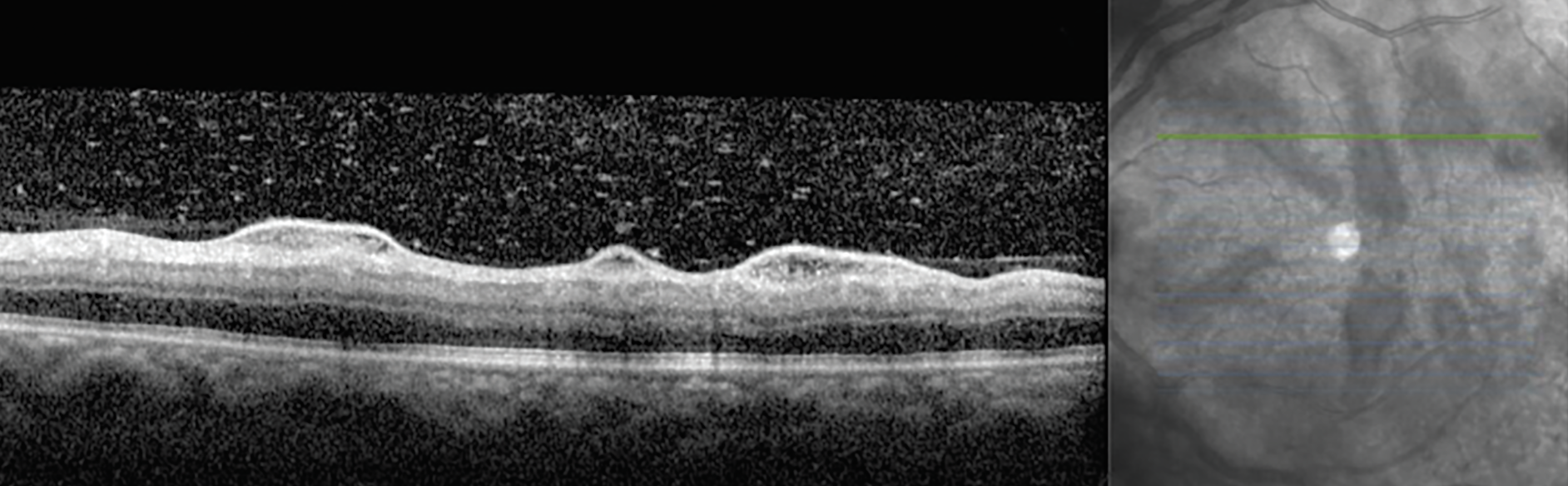

On examination, his visual acuities were 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. Intraocular pressures were 17mm Hg and 14mm Hg, and pupils were equally reactive to light. The left eye had significant conjunctival injection with ciliary flush and 4+ cell in both the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity. The posterior segment exam disclosed mild optic nerve edema, diffuse arterial sheathing and salient perivascular hemorrhaging throughout the fundus. Fundus photos and OCT scans were acquired (Figures 1 and 2).

|

Fig. 1. Fundus photo of the left eye on presentation reveals hemorrhagic vasculitis with mild diffuse vitreous haze. Click image to enlarge. |

Differential diagnoses for this case were post-op endophthalmitis, viral retinitis, hemorrhagic occlusive retinal vasculitis (HORV) and toxic anterior segment syndrome. Given the proximity to surgery, there was a high concern for infection. HORV was not favored, given no intravitreal or intracameral antibiotics (vancomycin) were administered at the time of surgery. Viral retinitis was less likely, given the clinical appearance and absence of immunocompromise. The patient did endorse a history of intravenous drug use, but stated his last use was six months prior to surgery. Upon further review of his cataract surgery post-op meds, he admitted to self-discontinuing topical antibiotics and steroids in the left eye just two days after surgery.

|

Fig. 2. OCT of the left eye at presentation reveals perivascular serous extravasation and vitreous cell. Click image to enlarge. |

Next Steps

A vitreous tap was performed on the left eye and sent for bacterial and fungal cultures. An anterior chamber tap was also performed and sent for viral cultures. Empiric intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime were injected. Voriconazole, an antifungal agent, was also administered given the reported history of intravenous drug use. The patient was started on topical prednisolone acetate hourly, cyclopentolate twice daily and oral valacyclovir 2,000mg three times daily.

|

|

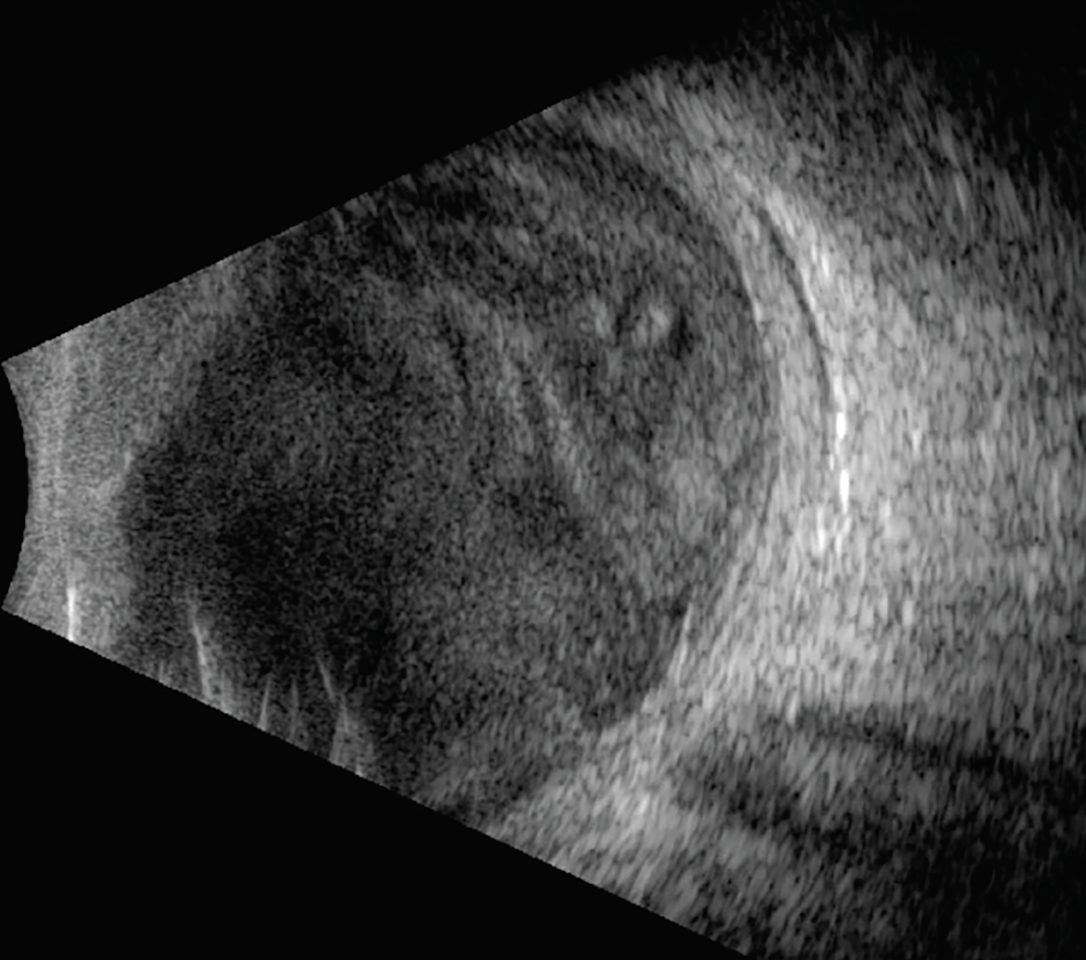

Fig. 3. Ultrasonography was performed due to severely reduced vision at follow-up. Dense vitreous opacities and early membranes are appreciable. Click image to enlarge. |

The patient missed his one-day follow-up but presented two days later with a significant decline in vision, from 20/25 to hand motion. There was an appreciable increase in intraocular inflammation including a hypopyon and vitreous membranes (Figure 3). A second round of intravitreal antibiotics was recommended, but the patient refused. The following day, lacking any clinical improvement, the patient agreed to undergo pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with intravitreal antibiotics and silicone oil placement. A vitreous sample taken at the time of surgery was positive for Serratia marcescens, confirming a diagnosis of a gram-negative bacterial endophthalmitis.

The patient’s infection was cleared, and the eye healed well after surgery. The patient eventually underwent silicone oil removal, which resulted in a final visual acuity of 20/40.

Endophthalmitis

Our patient’s presentation was interesting because of the excellent visual acuity at presentation, clear fundus visualization and atypical retinal findings. “Sometimes, early endophthalmitis can present with mild vitritis but exhibit salient retinal findings such as hemorrhage or vasculitis,” comments Jesse Sengillo, MD, to whom I referred this patient. “You always need to maintain a high suspicion in the setting of recent ophthalmic surgery.”

Endophthalmitis after an intraocular procedure or surgery is a devastating complication. Based on a review of over 8.5 million cataract surgeries performed in the United States, the prevalence of postoperative endophthalmitis is very low, hovering around 0.04%.1 Despite its rarity, as the rate of surgical comanagement is increasing, it becomes even more important for optometrists to recognize signs and symptoms of endophthalmitis.

Acute postoperative endophthalmitis occurs within six weeks of surgery, and the most frequently experienced symptoms are blurred vision, pain and photophobia. Classic exam findings of endophthalmitis include anterior chamber cell with or without hypopyon, progressive vitritis, conjunctival injection and ciliary flush. Delayed or chronic postoperative endophthalmitis is that which occurs after six weeks. These cases may present with slow progression of these findings as well as granulomatous keratic precipitates and inflammatory deposits on the intraocular lens surface.2

The most common causative pathogens are gram-positive bacteria of the ocular surface and adnexa, given their ubiquitous nature.3,4 Gram-negative bacteria are generally considered to present with worse visual acuities and portend a poorer prognosis due to their production of endotoxins and phagocytosis-resistant capsules, which leads to increased virulence.5 Fungal endophthalmitis is quite rare but may be slightly more common in tropical regions. Compared to bacterial endophthalmitis, fungal cases develop more slowly, over days to weeks, and are likely to have “clumps” of inflammatory material inside the eye as opposed to diffuse inflammation.6

Management

When a patient presents with findings suspicious for postoperative endophthalmitis, comanaging providers should have a very low threshold to contact the surgeon and/or refer to a retina specialist on an emergent basis. A combination of intravitreal antibiotics potent against gram-positive (e.g., vancomycin) and gram-negative (e.g., ceftazidime) bacteria is typically administered. Antivirals can be added if there is high concern for viral retinitis masquerading as bacterial endophthalmitis. Antifungals may be used in atypical cases or if clinical suspicion is high, particularly if the patient’s history supports this etiology (e.g., trauma, intravenous drug use).

Surgical management for endophthalmitis may be undertaken, as well. Vitrectomy can debulk the infection, provide a better culture sample, allow for direct visualization of the retina, and hasten visual recovery. The landmark 1995 Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study showed that for patients with very poor vision (light perception), the combination of early core vitrectomy with intravitreal antibiotics was superior to a vitreous tap and antibiotic injections alone in terms of final visual outcomes. A significant improvement in visual outcome was not seen for patients with hand motion or better visual acuity regardless of whether vitrectomy was performed.7

That study led to the wide adoption of “tap and inject” as the mainstay of treatment for postoperative endophthalmitis. Some specialists consider early surgical intervention, given the improved safety profile of modern vitrectomy compared to 30 years ago. One study from 2020 suggests early surgical intervention increases the likelihood of patients with postoperative endophthalmitis achieving 20/40 or better vision from an average of 50% to almost 80%.8

Regardless of the approach taken to manage endophthalmitis, the first step is recognition. Careful evaluation of clinical signs and symptoms of endophthalmitis combined with a high level of suspicion can allow for early identification of this visually devastating disease. Proper triage and referral can provide the best possible outcome for our patients.

Dr. Bozung currently practices at Bascom Palmer where she primarily sees patients in the hospital's 24/7 ophthalmic emergency department. She also serves as the optometry residency program coordinator. Dr. Bozung is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a member of the Florida and American Optometric Associations. She is a founding board member of Young OD Connect and serves on the editorial board for Review of Optometry. She has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Sengillo currently serves as chief resident at Bascom Palmer after finishing a vitreoretinal surgery fellowship. He will join faculty upon completion. His practice will focus on surgical retina and inherited retinal disease. He has no financial disclosures.

|

1. Pershing S, Lum F, Hsu S, et al. Endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in the United States: a report from the Intelligent Research in Sight Registry, 2013-2017. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(2):151-8. 2. Simakurthy S, Tripathy K. Endophthalmitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated August 25, 2023. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559079. Accessed March 15, 2024. 3. Kernt M, Kampik A. Endophthalmitis: Pathogenesis, clinical presentation, management, and perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:121-35. 4. Wilson BD, Relhan N, Miller D, Flynn HW. Gram-negative bacteria from patients with endophthalmitis: distribution of isolates and antimicrobial susceptibilities. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2019;13(1):54-6. 5. Tiecco G, Laurenda D, Mulè A, et al. Gram-negative endogenous endophthalmitis: a systematic review. Microorganisms. 2022;11(1):80. 6. Durand ML. Bacterial and fungal endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(3):597-613. 7. Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study: a randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(12):1479-96. 8. Dib B, Morris RE, Oltmanns MH, et al. Complete and early vitrectomy for endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: an alternative treatment paradigm. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:1945-54. |