Patient communication and education is a cornerstone of a successful optometric practice. Consider the amount of time you spend each day discussing disease diagnosis and management with your patients. How much of that patient “face time” are you dedicating to promoting wellness and disease prevention?

| |

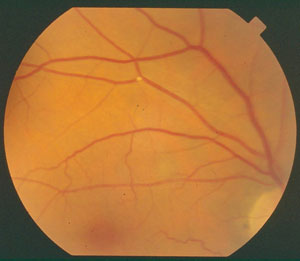

| This fundus image shows a Hollenhorst plaque, which can develop in patients with high cholesterol. |

Your patient base’s demographics will certainly influence how you answer. But, if your practice habits mirror those of the overall trends in health care in the United States, you probably spend a lot more of your time and effort treating disease than providing education and strategies to prevent it. In fact, 88% of the US health care budget is spent on disease treatment, compared with a paltry 4% on prevention.1

Optometrists, as primary care providers, are in an ideal setting to encourage wellness. Specifically with regard to retinal health, factors such as obesity, diabetes, smoking and family history have a profound, direct impact on disease outcomes.

This article takes a closer look at why—and how—optometrists should widen our focus to incorporate disease prevention.

Busting Wellness Myths

Shifting the focus to emphasize wellness instead of disease management isn’t an easy task. Many of the obstacles come from health care providers themselves. Let’s review, and debunk, some of the more common myths:

• Myth: “We should be emphasizing and educating patients about the best treatments for their diseases—talking about ‘prevention’ isn’t as beneficial in the big picture.”

Fact: About 50% of our health status is determined by lifestyle choices and wellness strategies. Genetics and environment only contribute about 20% each, and access to care makes up the remaining 10%.2 Consider this: If the average adult body mass index (BMI) is lowered by only 5% (for example, losing about 20 pounds for a 210lb, 5’10” tall person), obesity-related health care savings will amount to an estimated $29.8 billion in five years, and a staggering $611.7 billion in 20 years.3

Retinal Wellness By the Numbers

|

Obesity and smoking combined contribute to nearly a million deaths in the United States alone each year.4,5 These statistics represent our patients in our practices.

• Myth: “Anything a doctor says won’t really make a difference. People are just going to continue eating what they want and avoiding exercising no matter what doctors tell them.”

Fact: Studies show patients who receive counseling in a primary care setting, regarding better eating and exercise habits, more often took positive steps than patients who didn’t receive counseling. And those steps led to more weight loss and more exercise in the patients receiving counseling.6

• Myth: Issues of weight and obesity are inappropriate topics of discussion for an optometrist and are best left to a general primary care physician.

Fact: Maybe. But, although virtually every set of clinical guidelines in existence recommends that physicians counsel overweight and obese patients about nutrition and weight management, this only occurs about once in every eight visits, according to a recent survey. Worse, only one-fourth of physicians who responded to that survey said they felt they had adequate training to provide diet and exercise counseling.7 A mere one-third of medical schools meet the minimum number of hours in nutrition education recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.8

Also, many patients who are classified as overweight or obese avoid visiting a PCP for fear that they will be judged or ostracized for their weight.9 At the other extreme, a separate study found only 39% of obese patients surveyed had even been told by a physician that they were classified as obese.9 The gap between what needs to be done and what currently is being done must be filled. This is an “all hands on deck” public health crisis.

• Myth: “As an optometrist, I don’t feel qualified to make dietary or weight loss strategy recommendations to my patients—and I’m not even sure I’m permitted to do so in my state.”

Fact: If you feel under-qualified, that’s okay! We, as primary health care providers, aren’t expected to diagnose and manage every condition with which our patients present. We do, however, have the responsibility to connect patients to an appropriate care provider when a condition (or suspected condition) is outside of our scope of practice. A patient who has a high blood pressure reading along with retinal arteriolar attenuation isn’t walking away from your office with a prescription for a diuretic and a systemic beta-blocker. Instead, she leaves knowing she may be at risk for ocular and systemic consequences, and in the best-case scenario, she already has an appointment with a primary health care provider to confirm the diagnosis and manage it. Likewise, a patient with a BMI of 33 and retinal arteriolar attenuation isn’t visiting your optical to get appetite suppressants, a map to the gym and a two-week diet meal plan. However, that patient should leave with full knowledge of his ocular and systemic health risks, along with, ideally, an appointment with a qualified nutrition counselor, registered dietician or other medical or para-medical specialist who will recommend an appropriate eating and exercise plan.

| |

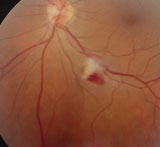

| These fundus images show retinal hemorrhages, a result of hypertension on the retina. |

Endocrinologists, retinologists, dermatologists and neurologists are among our referral targets—and obesity specialists should be as well.

• Myth: “Smokers already know the health risks. By me mentioning that they should stop smoking, I’m not only stating the obvious, but I also risk offending them.”

Fact: A large meta-analysis of 41 studies of more than 31,000 smokers found an improved quit rate for smokers who were counseled to do so by a physician.10 While the rate for unassisted quitting was 2% to 3%, counseling improved that rate by 1% to 3%. That might not sound like much as a percentage, but considering that tens of millions of Americans still smoke, that small percentage adds up to a meaningful number of your patients. The intervention by a health care provider does not need to be lengthy or involved to be successful—the same study found no difference in success based on the duration of discussion. Merely mentioning online support resources or suggesting a quitting technique such as nicotine gum was helpful.10

And remember, most people who smoke are ultimately successful in quitting only after multiple attempts.11 So don’t give up on your patients who fall off the wagon frequently.

• Myth: “Nobody who is overweight or obese wants to have it pointed out to them.”

| ||

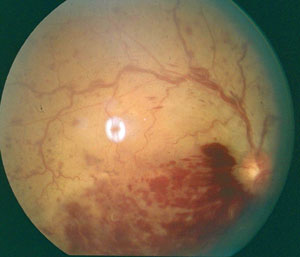

| Retinal vein occlusions, shown in these fundus images, are most often seen as a complication of hypertension, or less commonly, diabetes. |  | |

Fact: Few topics are as awkward to discuss with a patient as excess body weight. Many patients who have an unhealthy BMI want desperately to lose weight. They may feel isolated, frustrated or ashamed about their failure to do so.12-15 Handled with compassion and sincerity, this is an opportunity to build a strong trust relationship with your patient, rather than to alienate him.

Identifying At-Risk Patients

For many patients who need a referral to another doctor, the protocols and practices are clear and long established. For example, say a 62-year-old male patient complains of severe headaches increasing in frequency, along with a stationary blurry gray spot in the upper right portion of the visual field. Even before the dilated exam and automated visual field, you already have a plan to refer this patient to neurology for imaging and further care.

But for patients with excess adiposity absent any evidence of ocular findings, the path is less clear. How do you broach the topic of discussion? On what exam finding are you basing your pronouncement that the patient needs additional care? For what, and to whom, are you referring the patient?

Bear in mind, a high BMI is an independent risk factor for central geographic atrophy in AMD.22 Further, for patients with Type 1 diabetes, BMI is an independent risk factor for severity of diabetic retinopathy.23 Several studies show a correlation between BMI and cataract.24 While these conditions have complex and multifactorial causes, each presents a valid opportunity to open the dialogue about healthy weight with your patients.

Prevention Resources

To integrate wellness promotion into your practice, a bit of preliminary work is required. Find your local smoking cessation and weight management centers. A number of not-for-profit organizations with online resources are offered free to the public.

Many hospitals have free or low-cost smoking cessation programs. Many well-established weight reduction programs are available almost everywhere, either “live” or online. Some insurance programs cover weight and nutrition counseling. You can research these benefits for the plans that are prevalent in your area.

Who to Counsel About Weight and Physical Activity?

|

Specialty weight loss centers are featured at many hospitals, although many of these specialize in bariatric surgery. In most cases, to qualify as a candidate for surgery, patients must meet certain criteria (BMI over 35 or 40, for example, or a combination of a minimum BMI with one or more comorbid diseases).

Use caution when recommending weight loss centers that aren’t based on sound scientific principles. Opt instead for physicians or facilities that offer a combination of behavioral modification, menu planning with sustainable and realistic food choices, physical activity and pharmacologic support where needed.

Supplements

Educate yourself, if you haven’t already, regarding the various eye-specific supplements available. Remember, disease prevention and wellness promotion isn’t a one-size-fits-all program. Nutritional counseling, including the recommendation of specific supplements, is an important part of the optometric practice and should not be overlooked. In addition to the familiar practices of recommending omega-3 supplements for dry eye and carotenoids for AMD, there are also diabetes-specific supplements that may greatly benefit your diabetic patients. Patients with multiple systemic conditions may have higher micronutrient intake needs. Also, consider that many medications deplete certain key nutrients.25–27

Talking Wellness

Case One

Here’s how I handled a few actual case examples in which wellness promotion was appropriate.

Presentation: A 24-year-old Hispanic male presented with complaints of distance and near blur for six months. He reported “good health,” and took no medications or supplements. His most recent medical exam was more than eight years ago. Family history was positive for Type 2 diabetes and hypertension in both parents (and his father had suffered a mild MI at age 50). His calculated BMI was 44. He had mild myopic astigmatism and was correctable to 20/20 in each eye. The remainder of the examination was without pathology.

Patient education: After addressing this patient’s visual evaluation, I politely requested to address his weight issues. “The health status of your eyes today is good,” I said. “However, you fall into a higher-risk category for developing several other eye and systemic diseases based on your BMI. Is it okay if we talk about that?”

At this point, the patient acknowledged his weight problem and admitted the reason he didn’t see his doctor for regular checkups; he was afraid the doctor would “yell at him” for being so heavy. He said he had made several attempts at weight loss and, despite losing up to 50 pounds each time, always gained the weight back. He said he had given up on it.

| |

| Retinal macroaneurysm, as seen in this fluorescein angiography image, is another possible consequence of uncontrolled hypertension. |

I resumed my counseling: “Would you like to talk with someone about the methods that you have tried before and see if there are other techniques that might work better for you? There are many medications now that can be beneficial for weight loss. You might also be a candidate for weight loss surgery that your insurance may even cover under certain conditions. Can I give you some information to take home and consider? Whatever you decide, please know that we are here to support you and your health, so if you decide against

seeing one of these doctors, we still want you to come back for your eye checkups. This is a judgment-free zone.”

The key to successful communication in this delicate area is to focus upon health risks rather than body size. Establish the reasons for your concern first, and then seek agreement from your patient to discuss the topic. This important step is essential to a positive outcome. Not every counseling attempt is going to result in an immediate positive result. Give patients a safe space to partner with you in evaluation their health needs. Remember, you may be the only health care practitioner who has made a meaningful, compassionate effort to help address the issue. In my own experience, patients are usually relieved and grateful that someone took an interest, instead of being resentful or defensive.

Nearly always, once the subject is broached, I gain important additional history and insight into the patient’s health status that otherwise would not have been revealed. (For more tips, visit www.stopobesityalliance.org/wp-content/themes/stopobesityalliance/pdfs/STOP-Provider-Discussion-Tool.pdf)

Case Two

Presentation: A 55-year-old black female presented with a complaint of sudden vision loss in the left eye. She had high cholesterol and hypertension, and reported good compliance with a daily “water pill.” BCVA was 20/20 OD and hand motion OS. She had full to finger counting visual fields in both eyes, but central vision was absent in her left eye. Blood pressure was 150/102. Her right eye’s anterior and posterior segment health was unremarkable, aside from arteriolar constriction and A/V nicking; the left fundus showed a large (2.5 by 2.5 DD) central area of intra- and subretinal blood covering the central posterior pole adjacent to an apparent retinal arterial macroaneurysm superior-temporal to the macula. Her BMI was 31.

| |

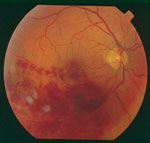

| Arteriovenous nicking, seen in this fundus image, is seen as one of the earliest signs of hypertensive retinopathy. |

Patient education: In a case like this, focus on the impact to the patient’s vision. Here’s what I told her: “The vision loss you are experiencing in your left eye is likely not going to be permanent. The blood that is partially blocking your vision will most likely clear over time. The more important issue is the cause of the bleeding, which is most likely your high blood pressure, and it is high today. With your permission, I’m going to write a note to your doctor to let her know what we found today, and to suggest that in addition to considering ways to lower your blood pressure, that she work with us to help lower your BMI to a healthier ratio. I know you told me before that it seems like you have so much weight to lose that it’s too much of a challenge, but believe it or not losing just 5% of your body weight will decrease your risk of disease consequences.”

Case Three

Presentation: A 54-year-old white female presented with complaints of diplopia in upgaze for four days. She was hypertensive but unmedicated. She has smoked a pack of cigarettes per day since high school, and had tried many times to quit, but it never “stuck.” She displayed signs consistent with an incomplete third nerve palsy without pupil involvement. Her blood pressure was 174/100.

Patient education: “I know this is something you’ve heard before, but the most important thing we can do for you overall is to help you succeed in smoking cessation. I have several resources for you, including other doctors who can prescribe helpful medications. Today, the more immediate problem is to make sure there isn’t something more serious than high blood pressure causing your eye problems. To be on the safe side, I’m going to order some imaging studies of your head and eye areas. Assuming that comes back normal, we will work together with your doctor to lower your blood pressure and help you kick the smoking habit for good.”

Healthy Patients

Finally, don’t overlook your healthy patients who do maintain a BMI in the healthy range. A few words of encouragement and acknowledgement of their healthy habits may reinforce their hard work and dedication, and increase the odds of maintaining those habits for a lifetime.

“Promoting wellness” in the optometric practice encompasses a variety of factors, including smoking cessation, achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight, proper nutritional intake, regularly getting adequate sleep, stress reduction and avoidance of high risk activities. Shifting to a prevention perspective instead of waiting for disease to develop before treating it might seem awkward at first, but ultimately can result in better patient health outcomes.

Dr. Reed is an associate professor at Nova Southeastern University College of Optometry in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. She teaches and writes extensively about ocular disease, ocular pharmacology and nutrition.

1. Health Care Costs: A Primer. Kaiser Family Foundation website. http://kff.org/report-section/health-care-costs-a-primer2012-report. Updated May 1, 2012. Accessed May 5, 2015.

2. Are America’s Physicians Prepared To Combat Our Nation’s Obesity Epidemic? Bipartisan Policy Center website. http://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Nutrition-Graphic-Final.pdf. Updated March 2015. Accessed May 5, 2015

3. F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens America’s Future 2013. Healthy Americans website. http://healthyamericans.org/assets/files/TFAH2013FasInFatReportFinal%209.9.pdf. Updated August 2013. Accessed May 12, 2015.

4. Laidman, J. Obesity’s Roll: 1 in 5 Deaths Linked to Excess Weight. Medscape Medical News, August 15, 2013.

5. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf. Updated January 2014. Accessed April 2015.

6. Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Hong PS, Tsai AG. Behavioral treatment of obesity in patients encountered in primary care settings: a systematic review. JAMA 2014 Nov 5;312(17):1779-91.

7. Bipartisan Policy Center White Paper. Teaching Nutrition and Physical Activity in Medical School; Training Doctors for Prevention-Oriented Care. 2013 [accessed 2015 April 1].

8. Adams, KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel, SH. Nutrition Education in U.S. Medical Schools: Latest Update of a National Survey. Acad Med 2010 Sep; 85(9):1537-42.

9. Why Weight? A Guide to discussing Obesity & Health With Your Patients. Stop Obesity Alliance. www.stopobesityalliance.org/wp-content/themes/stopobesityalliance/pdfs/STOP-Provider-Discussion-Tool.pdf. Updated 2014. Accessed April 2015.

10. Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, et al. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013 May 31;5:CD000165.

11. Hughes JR. Motivating and Helping Smokers to Stop Smoking. J Gen Intern Med 2003 Dec;18(12) 1053-57.

12. Puhl RM, Hueur CA. Obesity Stigma: Important Considerations for Public Health. AmJ Public Health 2010 June;100(6):1019-28.

13. Malterud K, Ulriksen K. Obesity in general practice: A focus group study on patient experiences. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28(4):205-10.

14. Wee CC, Davis RB, Huskey KW, et al. Quality of Life Among Obese Patients Seeking Weight Loss Surgery: The Importance of Obesity-Related Social Stigma and Functional Status. J Gen Intern Med 2013 February; 28(2):231-8.

15. Sikorski C, Luppa M, Kaiser M, et al. The stigma of obesity in the general public and its implications for public health – a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:661.

15. Cawley J and Meyerhoefer C. The Medical Care Costs of Obesity: An Instrumental Variables Approach. Journal of Health Economics, 31(1): 219-230, 2012; And Finkelstein, Trogdon, Cohen, et al. Annual Medical Spending Attributable to Obesity. Health Affairs, 2009.

16. Cawley J, Rizzo JA, Haas K. Occupation-specific Absenteeism Costs Associated with Obesity and Morbid Obesity. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 49(12):1317–24, 2007.

17. Wang YC et al. Health and Economic Burden of the Projected Obesity Trends in the USA and the UK. The Lancet, 378, 2011.

18. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society website. www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2012/. Updated 2012. Accessed May 5, 2015.

19. Trust for America’s Health and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens America’s Future. Washington, D.C.: Trust for America’s Health, 2012.

20. Health Effects of Obesity. The Obesity Society. www.obesity.org/. (accessed June 2013).

21. Clemons TE, Milton RC, Klein R, et al. Age Related eye Disease Study Research Group. Risk Factors for the incidence of Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the Age-Related eye Disease Study (AREDS) AREDS report no. 19. Ophthalmology 2005 Apr;112(4):533-9.

22. Kastelan S, Salopek RJ, Tomic M, et al. Body mass index and retinopathy in type 1 diabetic patients. Int J Endocrinol 2014 (2014), 387919.

23. Pan CW, Lin Y. Overweight, obesity, and age-related cataract: a meta-analysis. Optom Vis Sci 2014 May;91(5):478-83.

24. Chous AP, Richer SP, Gerson JD, Kowluru RA. The Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study (DiVFuSS): Beneficial effects of a novel, multi-component nutritional supplement evaluated in a double masked, double blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol, publication pending.

25. Skarlovnik A, Janic M, Lunder M, et al. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation decreases stain-related mild-to-moderate muscle symptoms: a randomized clinical study. Med Sci Monit, 2014 Nov 6;20:2183-8.

26. Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med, 2015 Feb; 10(1):93-102.

27. Nand B, Bhagat M. Serious and commonly Overlooked Side Effect of Prolonged Use of PPI. Am J Med, 2014 Sept; 127(9):e5.