|

A 50-year-old white male presented emergently for torsional diplopia in left gaze, left upper eyelid drooping and severe stabbing pain around the left orbit for one week. His medical and ocular histories were unremarkable, and he was not taking any medications. He reported no drug allergies and his family and social histories were unremarkable.

His best-corrected visual acuities were 20/20 in each eye. On primary gaze, he showed mild ptosis and exotropia of the left eye. Ocular motilities were full in the right eye and minimally limited in supraduction and adduction in the left eye. The interpalpebral apertures were 6mm OD and 4mm OS. Pupils were equal, round and reactive to light with no afferent defect. We conducted a neurologic exam, and additional testing revealed no associated cranial nerve involvement.

IOPs measured 16mm Hg OU. The anterior segment exam was unremarkable. Fundus exam showed healthy lenticular, vitreous, vascular and retinal structures. The optic nerves showed a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.15 with good perfusion and healthy, distinct margins.

Initial Diagnosis

Based on symptoms and clinical findings, we diagnosed him with partial left third nerve palsy. The presence of a partial third nerve palsy in a patient younger than 60 without vascular risk factors prompted us to order emergent erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and c-reactive protein (CRP) to rule out vasculitis, as well as contrast-enhanced MRI and angiography to discount an aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery. Both were unremarkable.

|

| Follow-up revealed blurred margins of the left optic nerve. |

In the absence of intracranial pathologies and vasculitis, we leaned towards a diagnosis of small vessel disease, with the periorbital pain secondary to ischemia. We scheduled him for evaluation with his general physician and comanaging neurologist. A physical exam and laboratory studies revealed undiagnosed primary hypertension and hyperlipidemia. He was started on the appropriate medication and aspirin.

The Plot Thickens

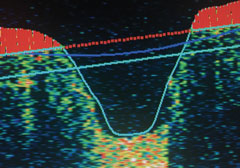

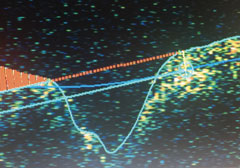

A follow-up exam one month later revealed complete resolution of the third nerve palsy. However, his anterior segment exam was remarkable for mild diffuse ciliary injection and grade 1 anterior chamber cells of the left eye. Dilated fundus exam revealed anterior vitreous cells, hemorrhagic edema of the optic nerve, choroidal folds within the macula, and multiple midperipheral detachments of both the neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) of the left eye—all consistent with a diagnosis of panuveitis.

We referred him for fluorescein angiography, which confirmed our findings. Visual fields revealed mild enlargement of the physiologic blind spot of the affected eye.

Given the recent clinical findings and previous partial third nerve palsy, we ordered the following tests: complete blood count with differentials, comprehensive metabolic panel, ESR, CRP, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, Lyme antibody, cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, quantiferon-TB gold, angiotensin-converting enzyme and lysozyme. Additionally, we ordered a CT of the chest to discount lung infiltrates, which can occur in tuberculosis, sarcoidosis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Results were unremarkable for all tests.

In the absence of laboratory-confirmed systemic disease, the most common cause of panuveitis with multiple serous neurosensory detachments is Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome. The patient was referred back to the neurologist for lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis; results confirmed leukocytosis (increased white blood cell count). Based on the revised criteria, we made a diagnosis of probable VKH. The patient was started on 80mg of prednisone and 150mg of ranitidine.

Currently, the panuveitis has resolved and the prednisone was tapered. The patient is taking 40mg of prednisone daily and will start subcutaneous methotrexate injections to reduce the long-term side effects of systemic steroids.

|

| Normal nerve fiber OD. |

|

| Nerve fiber layer edema OS. |

|

| OS midperipheral detachments of the neurosensory retina and RPE. |

The ABCs of VKH

VKH is a multisystemic disorder characterized by granulomatous panuveitis with serous retinal detachments often associated with neurologic and cutaneous manifestations.1 Vogt, Koyanagi and Harada described a wide spectrum of clinical findings that incorporated a similar pathology involving an overactive immune response to melanocytes.1 To clarify the diagnostic features of the disease, the International Committee on Nomenclature established revised criteria and a new three-category classification system: complete, incomplete and probable.2

Complete VKH is characterized by bilateral multifocal serous retinal detachments, evidence of previous early manifestations of the disease (including nummular chorioretinal scars and RPE clumping), as well as CSF leukocytosis, cranial nerve palsies, meningitis, tinnitus, alopecia, vitiligo and poliosis.2

Incomplete VKH is characterized by a combination of neurologic and auditory disease manifestations or integumentary signs, but not both.2

Probable VKH disease only manifests ocular findings.2

Although the etiology of VKH is uncertain, the presence of HLA-DR4 in affected individuals highlights the possibility that the disease has an autoimmune pathogenesis against an antigenic component shared by uveal, dermal and meningeal melanocytes.3 Most cases are sporadic, but some suggest that certain ethnic groups share a common immunogenic predisposition for an autosomal recessive trait.4 In one study of patients with VKH disease, 50% were white, 35% African American and 13% Hispanic—with a large percentage of affected individuals having remote Native American ancestry.5 While the age of onset is variable, it most commonly occurs within the third decade, affecting females more than males (2:1).5

VKH diagnosis is primarily clinical. The differential diagnosis includes sympathetic ophthalmia, sarcoidosis, primary intraocular B-cell lymphoma, posterior scleritis and uveal effusion syndrome.6 Long-term ocular complications can be both reversible and irreversible, the latter of which may include cataract, glaucoma, subretinal fibrosis, choroidal neovascularization and optic atrophy.

Treatment efficacy largely depends on early diagnosis and high-dose systemic corticosteroid therapy. Once initiated, steroids should not be discontinued until there is significant improvement in the ocular findings.1 Neurologic and auditory manifestations also respond well to corticosteroids, with immunomodulatory agents being used as adjunctive treatment or primary treatment when corticosteroid side effects are not tolerated. Conversely, integumentary signs—including poliosis, vitiligo and alopecia—persist and progress despite treatment.

In this particular case, the initial presentation of partial third nerve palsy was a precursor to fundus findings consistent with VKH. Patients with neuro-ophthalmic disease require detailed anterior and posterior segment examination to look for active or previous findings of intraocular inflammation, since a low threshold for VKH disease is important to establish an early diagnosis and prevent long-term systemic and ocular morbidity.

|

1. Andreoli CM, Foster CS. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006;46:111–2. 2. Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131(5):647-52. 3. Davis JL, Mittal KK, Freidlin V, et al. HLA associations and ancestry in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sympathetic ophthalmia. Ophthalmol. 1990;97(9):1137-42. 4. Levinson RD, Du Z, Luo L, et al. KIR and HLA gene combinations in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Hum Immunol. 2008;69(6):349-53. 5. Nussenblatt RB. Clinical studies of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada’s disease at the National Eye Institute, NIH, USA. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1988;32(3):330-3. 6. Pahk PJ, Todd DJ, Blaha GR, et al. Intravascular lymphoma masquerading as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008;16(3):123-6. |