|

The evolution of pharmaceutic marketing in eye care over the past century is fascinating. The earliest ads—those from the patent medicine era of the late 19th century—promoted cures for all manner of eye conditions with little, if any, information on their efficacy and safety. No mentions of active ingredients existed, only a prodigious list of ailments each product would cure. In fact, about the only claim not made is the ability to cure blindness.

It appears that the most important selling point for these potions was a product endorsement from one of “the greatest ophthalmic surgeons” or other similar individuals of excellent repute. Apparently, the only requirement for safety and efficacy was to have a bloated pundit endorse the product. In this respect, perhaps, times haven’t really changed that much.

Reproduced here are a few representative ads that ran in The Optical Journal from the period 1895-1901. Let’s consider what they say about the culture of their era—and ours.

Faith Healers

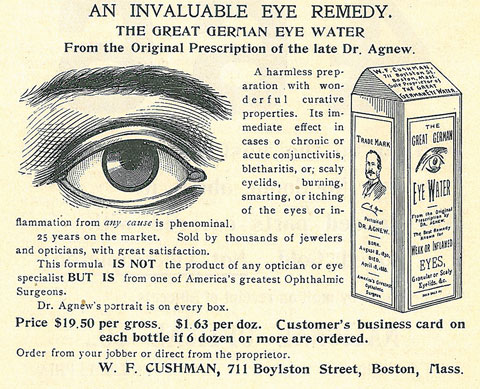

In truth, some of these products may actually have lived up to at least a few of their claims, though the efficacy may lie in the faith of the patient more than the ingredients in the bottle. The “Great German Eye Water” as seen in Figure 1 probably did flush away allergens, relieve itching and lubricate dry eyes. Likely there wasn’t anything more in this product than readily available drinking water, but it’s quite possible that the inclusion of the portrait on the bottle—the great Dr. Agnew—led to a significant placebo effect.

|

| Fig. 1. “Dr. Agnew’s portrait is on every box” assures this 1901 ad that trades on the name of “one of America’s greatest Ophthalmic Surgeons.” Click to enlarge. |

This concept is actually reasonable. Experts say a relationship exists between how strongly a person expects to see results from a treatment and the likelihood that the treatment elicits some effect. The interaction between a patient and health care provider can be substantial in terms of generating such an effect.1 Thus, a patient’s belief that Dr. Agnew himself held valid the miraculous claims of the product may have been enough to create a placebo effect.

Same goes for Dr. Lawton’s Eye Lotion from 1895, seen in Figure 2, which trades on the name of its proprietor to influence both the Victorian “opticians and jewelers” who stocked it as well as the customers to whom they resold it.

Pflogging It

|

| Fig. 2. This 1895 ad hawks an “eye lotion” that “sells readily.” |

Antiphlogistine is a rubefacient introduced in 1893 by Denver Chemical of New York, though this ad, seen in Figure 3, dates to 1901 from a pair of New Hampshire optometrists, Brown & Burpee. Produced and available in Canada to this day, it is a popular product for the treatment of tough muscle, arthritic and rheumatic pains, as well as bursitis.

Rubefacients are topically applied and produce redness of the skin through capillary dilation; subsequently, they increase vascular circulation. While this mechanism explains the possible effects of antiphlogistine and rubefacients on inflammation, no evidence exists to support their use for this indication. When applied to the eye or periorbital region, local effects could be perceived as beneficial (the ad does not state how the potion is to be used). The assumption by the patient may be that if it burned when applied to the eye—as it seems likely it would—then it must be working.

|

| Fig. 3. “It is as harmless as it is potent,” claims this 1901 ad. |

Marketing Today

Medications now come with detailed product inserts wherein manufacturers list every known contraindication and adverse effect, but only a narrow sliver of detail on their use, as indications and dosing are beholden to the study design of the pivotal trials—in effect, a 180° turn from how it was a century ago.

When physicians do present promotional talks for new drugs, they are typically given a company-derived promotional presentation that emphasizes adverse effects—speakers are not allowed to stray from the message or modify the talk in any way. Regulations now dictate that we either refrain from speaking of any non-labeled uses of a medication or expressly state that a suggested use is off-label.

|

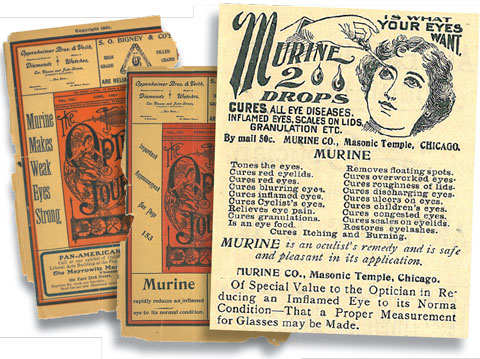

| Fig. 4. Murine was big business at the turn of the century, even getting ad space on the magazine cover. The workhorse drug was apparently able to “cure” an array of ills including “cyclist’s eyes” and “children’s eyes.” Plus, it’s an “eye food,” too! |

Drug companies now try to influence physician prescribing habits by appealing to the most sacred customers—their patients—through direct marketing on television and in print. These direct-marketing drug ads implore patients to “ask your doctor” about the appropriateness of the therapy. While print ads now contain powerful graphics designed to garner patients’ attention, turn the page and you will find at least another page of small print detailing risks and safety precautions. These warnings are so prevalent, in fact, that one wonders why anyone would want to use the product in the first place.

FDA FactsThe Food and Drug Administration—created in 1927 partly in response to such cavalier marketing, and given greater regulatory power in 1938—is responsible for protecting the public health by assuring the safety, efficacy and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, medical devices, our nation’s food supply, cosmetics and products that emit radiation.3 Most doctors are at least vaguely aware of the FDA’s role, and yet many view the regulatory body as an impediment to rapid progress in health care. In spite of this perception, the organization plays a vital role in ensuring the claims of medical products are grounded in solid science—not speculation or sophistry as in the freewheeling ads of yore. The FDA is also responsible for advancing public health by helping to speed innovations that make drugs more effective, safer and more affordable, and by helping the public obtain accurate, science-based information to make informed decisions on medications and foods. The agency also regulates the manufacturing, marketing and distribution of tobacco products to protect the public health and to reduce tobacco use by minors.3 Finally, the FDA plays a significant role in the nation’s counterterrorism capability. It fulfills this responsibility by ensuring the security of the food supply and by fostering development of medical products to respond to deliberate and naturally occurring public health threats.3 |

But even with safeguards in place, the balance can still be off the mark. Recently, a new generation of blood thinners led to a spike in deaths (relative to the standard-bearers in anticoagulants like warfarin) from uncontrolled bleeding. The blood thinners were touted in commercials as more convenient than warfarin because they require less monitoring. Hailed by the likes of Arnold Palmer, the novel anticoagulants were supposed to make life easier. But those benefits came with risks that, when ignored, ultimately resulted in potentially avoidable deaths. Since then, warnings now seem to feature prominently in commercials of Mr. Palmer hitting a golf ball. While the warning statement existed all along, “May result in uncontrollable bleeding” now catches one’s ear more easily. Is it appropriate for that to be the lingering message patients take away?

Other times, manufacturers overpromote a particularly favorable study outcome. For example, the opiate abuse epidemic has been exacerbated by overprescription justified by the results of one study—now known to be false—which stated that the adverse effects of prescribing opiates were minimal. Educators used the study to influence an entire generation of physicians. And it wasn’t long ago that drug reps themselves also roamed the medical schools, soliciting these clinicians to use their company’s drugs.

These examples, amid myriad others, reflect the disjointed and somewhat schizophrenic modern approach to pharmaceutical marketing: use advertising’s tools of persuasion, but undercut the message with a litany of warnings; hire doctors to educate, but keep them from speaking freely about what they know to be true.

No Going Back

In spite of our contemporary concerns, remember where we came from. We concern ourselves with the possibility of conflicts of interest at conferences and worry that our patients cannot afford a drug. But, better that we debate which drug is right for our patients based on both cost and efficacy than to sell them a bottle with a famous face on it and hope for improvement through faith in the portraits of the Dr. Agnews of the present day.

While many physicians may wring their hands over the sometimes glacial pace of medication approval, few would disagree that knowing the effectiveness and safety of approved medications is a must. So it comes down to this: We can go back to a time when untested potions promised the world and doctors had no way to verify the claims, or we can deal with the FDA, warts and all, a regulatory body that has provided a level of public protection from the would-be snake oil salesmen of our own time.

|

1. WebMD. The Placebo Effect: What Is It? WebMD. www.webmd.com/pain-management/what-is-the-placebo-effect?page=2. Updated 2/23/2016. Accessed June 2016. 2. Care Pharmaceuticals. www.murine.com.au/products/eye-drops/murine-clear-eyes. Murine. Accessed June 2016. 3. Food and Drug Administration. What We Do. www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo. Accessed June 2016. |