|

The response to stereo testing indicates how well a patient’s binocular system is functioning. If stereo is present, we know the patient is using the information flowing through both of their eyes. One way to optimize your patient’s needs is to perform refraction with their habitual prescription and then with their new prescription to see if stereo improved. If it did, then you should feel confident the new prescription will benefit the patient. But, not so fast.

|

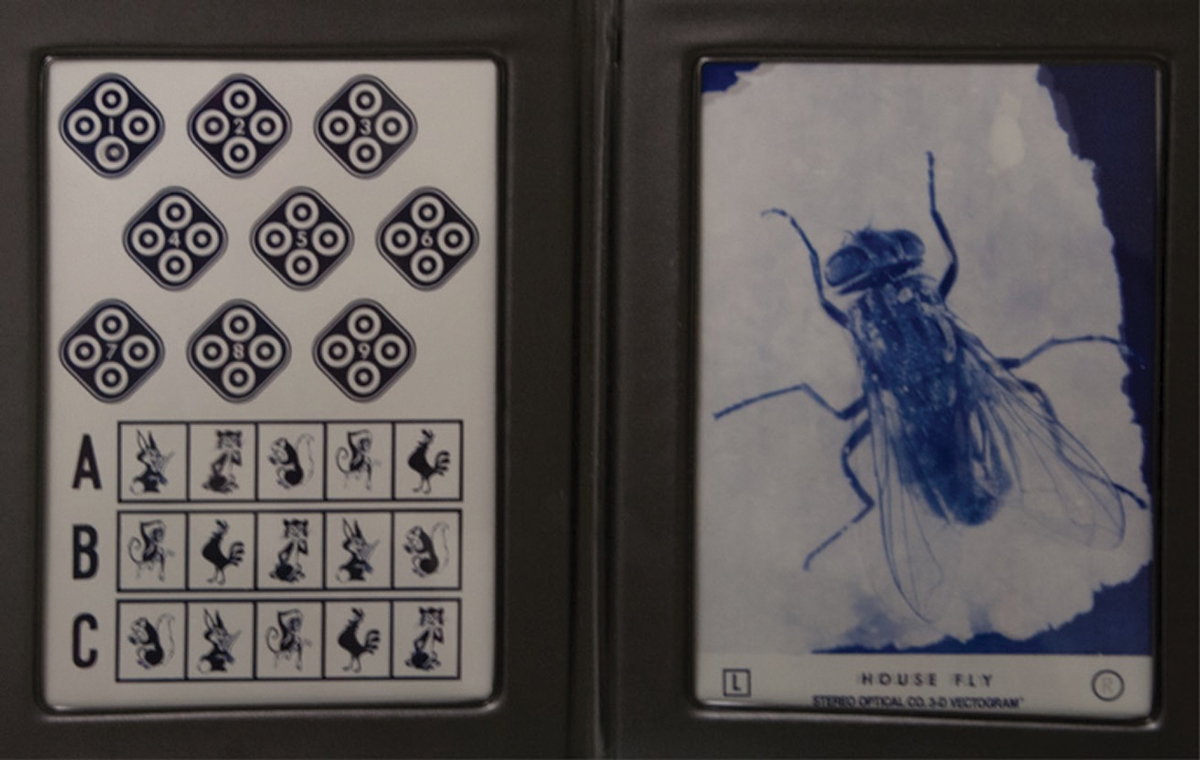

Fig. 1. The full Stereo Fly test book with Wirt circles on the left. Click image to enlarge. |

The Evolution of Stereo

Stereo tests have evolved from the good old days when clinicians didn’t know the difference between local and global stereo—all we knew was the Stereo Fly (Figure 1). Show it to people for the first time and watch their reaction. We all remember telling our patients to “pinch the wings” and watching as they recoiled from the image jumping off the page. Fun times! But the real test was the Wirt circles.

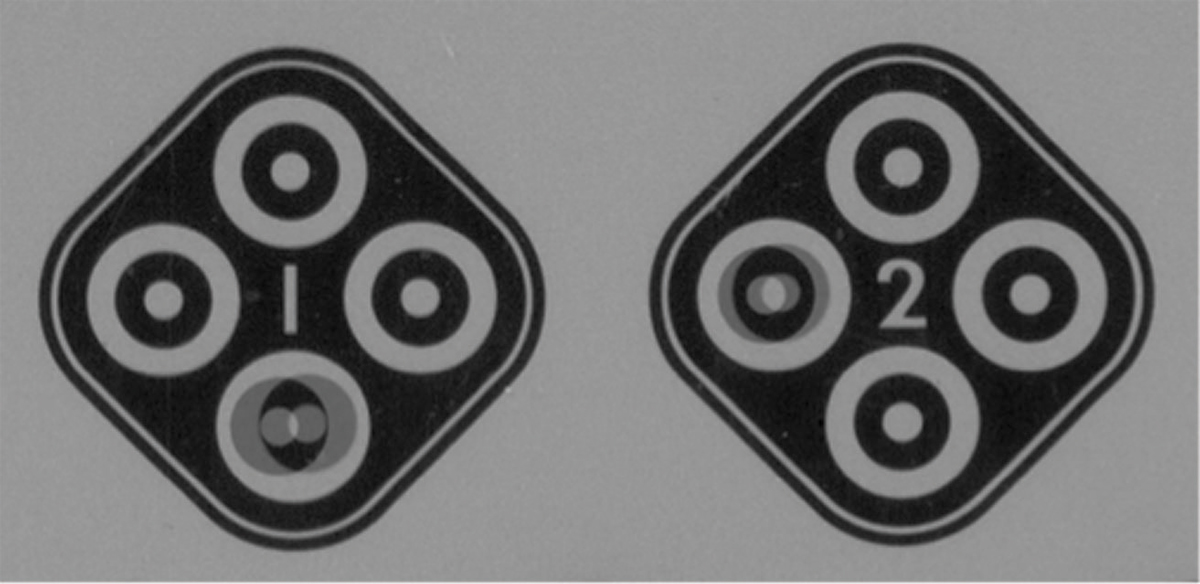

When conducting the Wirt circle test, few of us concern ourselves with monocular cues to depth. The lower circles in the diamond with the “1” in the center look fuzzy or appear in twos when viewed without the stereo glasses (Figure 2). With the stereo glasses on, only one of the two circles shifts to the right or left, depending on which eye the person is looking through centrally. These monocular cues to depth tend to work well until about 70 seconds of arc on the Wirt circle test. Measures up to 70 seconds of arc may or may not be actual measures of binocular stereopsis and may represent excellent use of monocular cues.

|

| Fig. 2. The first two Wirt circles. Click image to enlarge. |

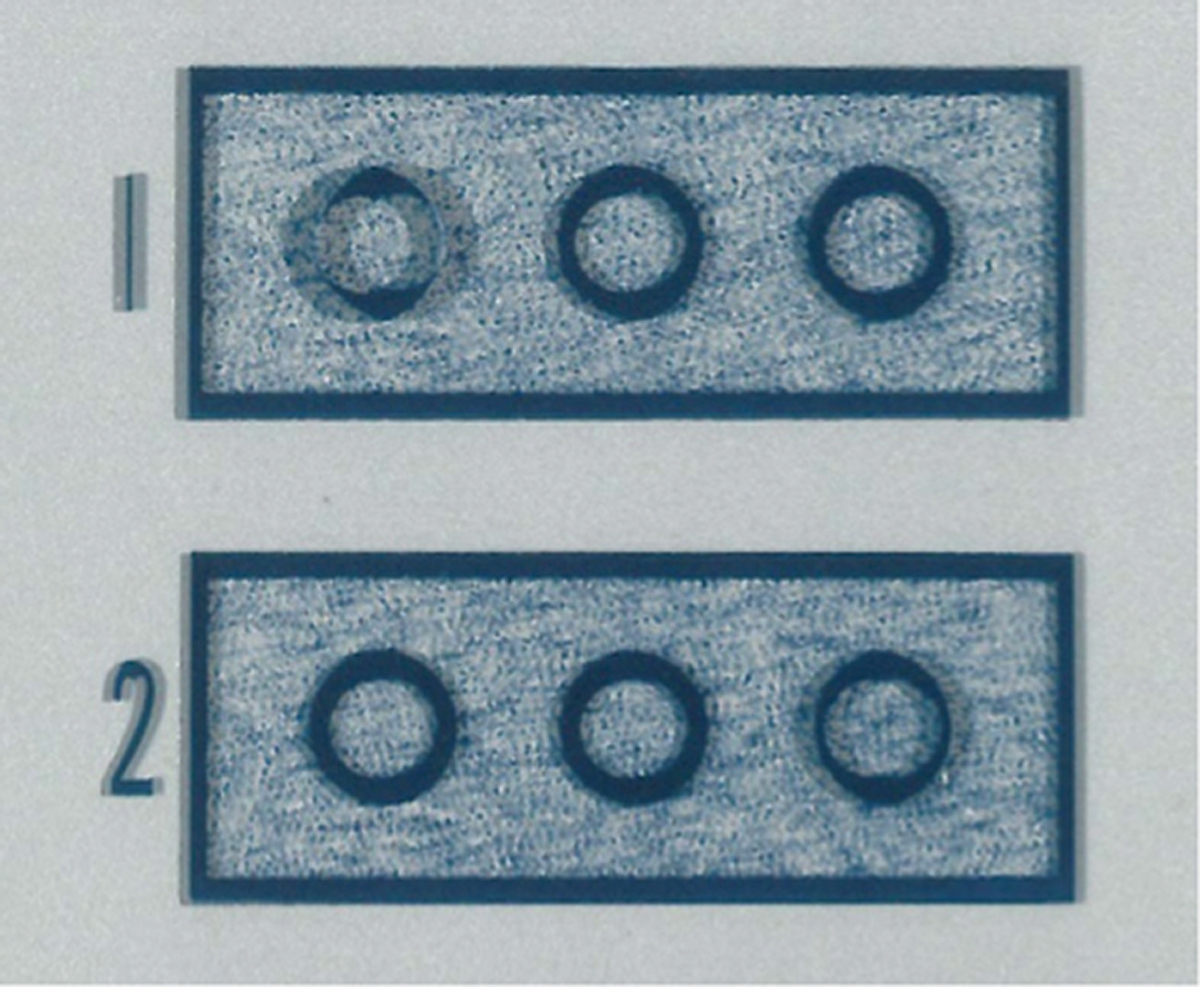

Then came random dot tests, of which there are two different kinds. In one, the Wirt circles lie on top of the random dot pattern background (Figure 3). Here again, the monocular cues are easily discernible. Of the three circles, one clearly looks blurred without the stereo glasses. Put the glasses on, cover one eye—or suppress the central vision through one eye—and now one of the circles has shifted slightly. You can guess well down to 70 seconds of arc without really having good binocularity or, therefore, good stereopsis.

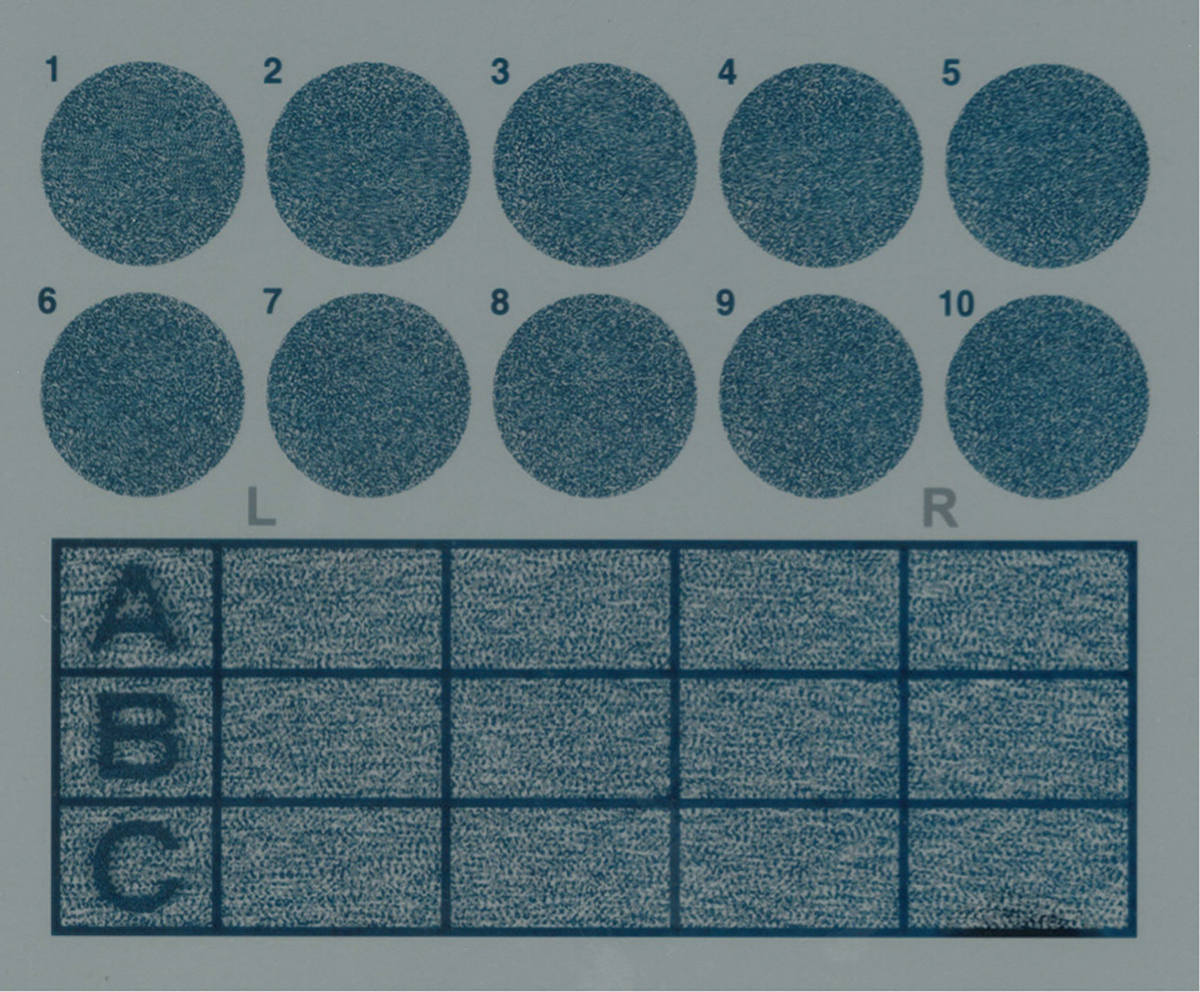

Global stereo targets, on the other hand, are all done with random dot patterns (Figure 4). The background shows the same dots in the same place to both eyes. If you are truly binocular, when figures appear, the dots in that area will shift right in one eye and left in the other, relative to the unshifted dots in the background. Depending on the direction of shift, the person will perceive the dots forming the figure, circles in this instance, as shifting closer or further than the plane of the test.

In each of the circles are four circles, three of which are pushed inward behind the plane of the test and one of which is shifted out closer to the observer by the same amount the other three are inset. Being able to correctly identify the nearer circle is a good sign. The monocular cues, which some claim are still present, are much harder to detect under these circumstances.

One study found that several participants were able to get to about 70 seconds of arc on the Wirt circles but were worse than 400 seconds of arc on the global Random Dot 3 test.1 Another showed that there are no monocular cues to depth with full random dot tests, which are all global.2 These researchers discovered some non-stereoscopic cues that could be used to deceive the test, but they were unique to the design of the Stereo Butterfly test used in their work.2

Before the advent of global stereo testing, we assumed the measurements from the standard tests were accurate. However, now we know that Wirt circles have fairly strong cues that may falsely lead us into believing the prescription we are about to give is a good one, at least as far as binocularity is concerned.

Upon further review, however, we realized that we were overestimating the level of binocular performance of some of our patients. It is important to make sure we don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, so to speak. In this case, the baby is improvement in binocularity and stereopsis, and the bathwater is tests that do not always tell the full story. What we should be doing is continuing to use stereopsis to measure the level of binocular improvement and confirm our refraction. Let’s take a look at a case example to see how this applies.

|

Fig. 3. Wirt circles with random dot background. Click image to enlarge. |

Case Example

A nine-year-old was referred in for a vision therapy evaluation secondary to the diagnosis of amblyopia. Her uncorrected visual acuities were 20/20 OD and 20/30 OS. Her manifest refractions were +0.75 OD and +3.00 OS. The visual acuity in her right eye was still 20/20 with the +0.75, but her left eye only improved to 20/25- with the +3.00. Prescribing was deferred to us following the vision therapy evaluation, but the referring doctor had indicated his desire to give full plus in both eyes.

At the initial evaluation, we used Wirt circles and recorded 70 seconds of arc. This is a routine part of our chair test, which occurs before the refractive data from the rest of the testing is available. Knowing that the patient could have used monocular cues to attain this result, we recommended the global stereopsis test. Without lenses, the patient only made it to 400 seconds of arc on the large global shapes. This shows that she had a functioning binocular and stereo-capable system but could not see the stereo without any plus.

|

Fig. 3. Wirt circles with random dot background. |

We then suggested the patient put +1.25 over her left eye only and repeat the test. The results were surprising, as the stereopsis results came out to 30 seconds of arc with the fully global stereo test. For demonstration purposes, we also did stereo testing through +2.25 and +3.00 over the patient’s left eye. There was no further improvement with more plus.

There are many other factors that must be taken into consideration to derive the amount of plus we should prescribe. We can see that partial plus may yield a large improvement in stereo, but the addition of more plus may change nothing. So don’t be fooled into thinking your patient has good stereo with the prescription you are about to give as measured by the Wirt circles. Using a global stereopsis test will help you help your patient attain a higher degree of binocularity and, therefore, better visual performance.

| 1. Bodack M, Wilcox J, Harris PA. Comparison of three tests of stereoacuity. Poster presented at the American Academy of Optometry; New Orleans, LA; 2015. 2. Chopin A, Chan SW, Guellai B, et al. Binocular non-stereoscopic cues can deceive clinical tests of stereopsis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5789. |