Enteroviruses are most well-known for how they infect the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory system, and although it’s possible for them to infect the eye, these manifestations have rarely been described in the current literature. However, a new retrospective cohort study observed enteroviruses (EV) in 0.66% of its polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive ocular infections. Researchers stated this is the first time EV has been implicated in cases of conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis and corneal endothelial failure.

This study, published in Ophthalmology Science, included 12,289 ocular viral multiplex PCR specimens collected at The Royal Victorian Eye & Ear Hospital in Australia between April 2015 and May 2020. Specimens were tested for Herpes simplex virus type 1, Herpes simplex virus type 2, Varicella zoster virus, Cytomegalovirus, adenovirus and EV. A total of 3,687 specimens were positive, of which 81 (0.66%) were EV positive. Of those, 52 came from conjunctival samples, 28 from corneal samples and one from an aqueous sample.

|

|

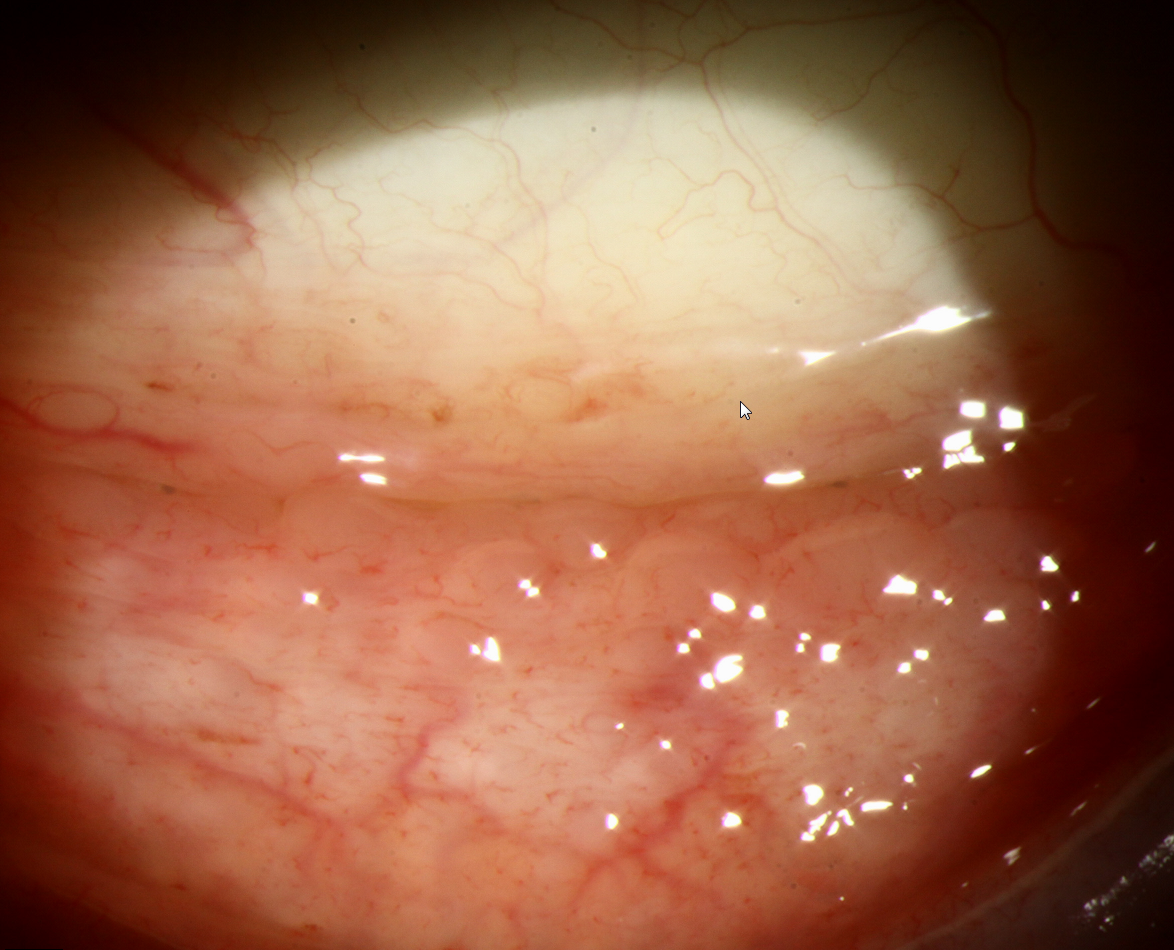

For the first time researchers identified enteroviruses in 0.66% of specimens tested for viral polymerase chain reaction, which manifested mostly as unilateral conjunctivitis and keratitis. Follicular response was common in the cases documented in this study. Photo: Chris Sindt, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Conjunctivitis was the most common presentation of EV, followed by corneal signs. Seventy-two of the 81 patients presented with unilateral signs; nine presented with bilateral disease, including one patient with a co-infection with streptococcus pneumoniae and one patient who was also adenovirus PCR positive.

The authors stated that EV is usually self-limiting, although persistent infection in non-ocular infections have been reported. “In our cohort, the ocular signs were similarly self-limiting, except patients with concurrent HSV disease who were treated with antivirals (acyclovir ointment or oral valaciclovir) and patients with concurrent bacterial infection who were treated with topical ofloxacin as per standard clinical practice,” they wrote.

There’s no known effective treatment for EV infections, and in this cohort, EV conjunctivitis and keratitis patients who attended a follow-up appointment resolved clinical signs with a median of seven and 13 days, respectively. Four patients had a prolonged recovery period, each of whom has a concurrent viral or bacterial infection.

There has been no prior study on the presence nor duration of EV shedding in the tear film, the authors said. “While PCR testing is sensitive in detecting the presence of viral RNA, it does not indicate active infection or prolonged infectiousness, nor equate to its ability to transmit infection, which may be influenced by numerous factors, such as virus load, exposure time and host situations,” they wrote in their paper. “Interpreting the difference between ongoing viral shedding of non-infectious RNA and ongoing replicating viable virus is difficult.”

Although this is the first study to implicate EV in these cases, diligence on the part of physicians will help further recognize their prevalence in ocular infections.

Boynes A, Pham C, Jardine D, Chan E. Ocular manifestations of enterovirus: An important emerging pathogen. Ophthalmol Sci. May 28, 2024. [Epub ahead of print.] |