|

Q:

A patient presented with progressive bilateral vision loss and swollen optic nerves OU. What are some considerations?

“All optometrists should be comfortable with neuro cases so that a presentation that raises suspicion can be addressed quickly,” says Steve Holbrook, OD, of The Eye Center of Southern Indiana.

Dr. Holbrook received an emergency Sunday call from a frantic daughter whose 78-year-old mother was experiencing gradual bilateral loss of vision for seven days that continued to worsen. She had been seen by her optometrist four days prior with best-corrected acuity of 20/50 OD and 20/80 OS. She was pseudophakic and had mild atrophic AMD and early nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy without macular edema. Her main finding at that visit was bilateral swelling of the optic nerves. Her health history included hypertension, high cholesterol, atrial fibrillation, anemia and obstructive sleep apnea on CPAP. She was sent to the local emergency department (ED) with the working diagnosis of papilledema and underwent CT, CTA and MRI scans, which were all negative. With no mention of her optic nerves, she was released to her primary care physician in three to five days. With her vision continuing to decline, she called her OD back the following day.

“The optometrist referred her to us but we were unable to get the patient on the phone that same afternoon,” Dr. Holbrook noted. “Her vision continued to decline until two days later, when the daughter called the after-hours service not wanting to wait until Monday.”

|

|

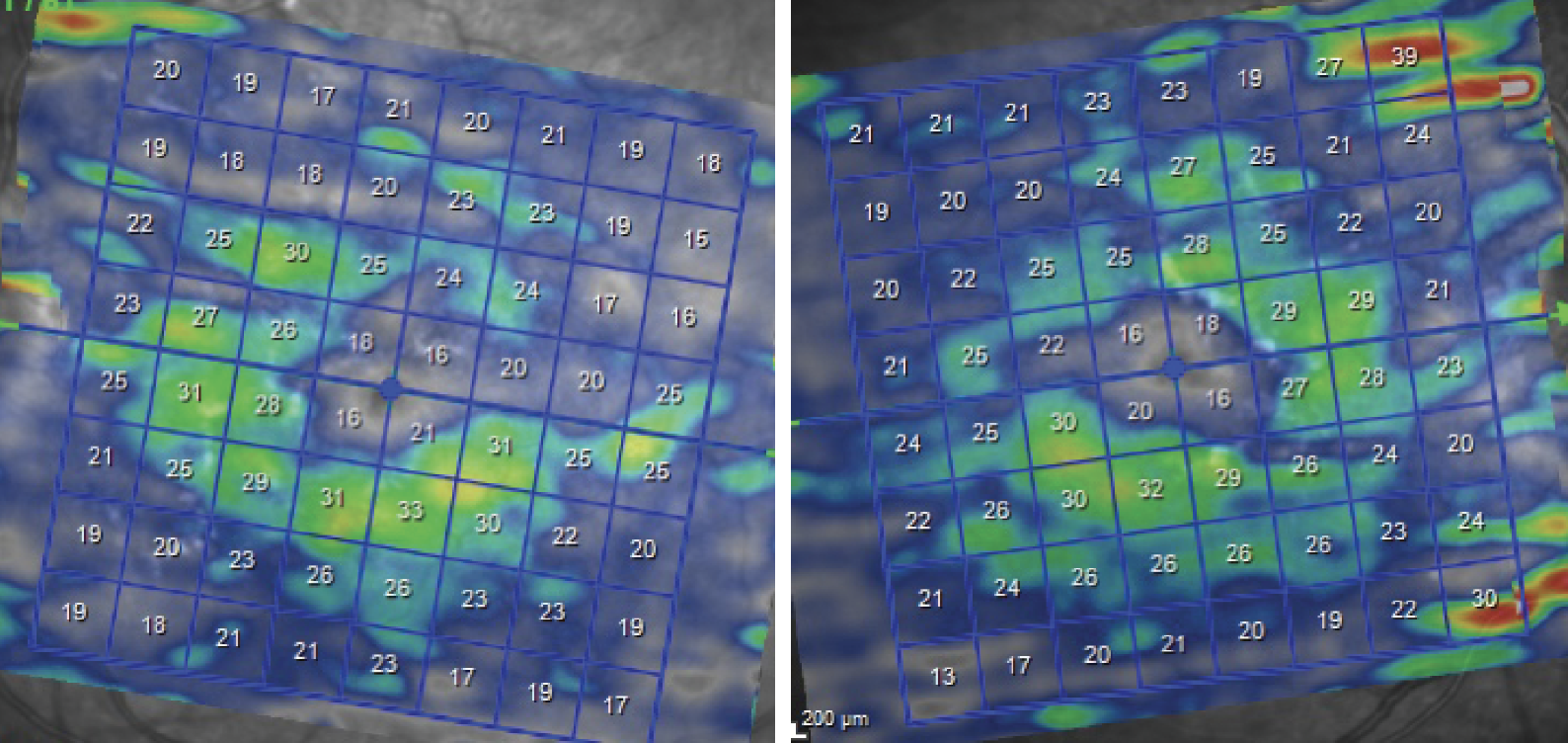

Heidelberg OCT of the ganglion cell layer shows extreme thinning in both eyes. Click image to enlarge. |

Scanning in the Wrong Places

After realizing over the phone that the patient now had counting fingers vision in each eye, Dr. Holbrook sent her to the regional teaching hospital in Indianapolis for an urgent neurologic evaluation. The patient had blood work done, a repeat MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast and was scheduled for a lumbar puncture.

The MRI of the orbits was consistent with bilateral optic neuritis, showing abnormal enhancement in the intraorbital segment of the optic nerves with perineural inflammatory changes. She was further evaluated for paraneoplastic syndromes with CT chest, abdomen and pelvis, cerebrospinal fluid analysis and an MRI of the cervical and thoracic areas. Her myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody titer came back positive at 1:640 (normal is <1:10). The antibody for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (aquaporin-4 or anti-AQP4) was negative.

“Our patient was diagnosed with MOG optic neuritis,” Dr. Holbrook says. “This is a fairly newly described condition that optometrists should be more aware of.”

Demyelination Diagnosis

MOG antibody-associated disease is an inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system characterized by attacks of immune-mediated demyelination predominantly targeting the optic nerves, brain and spinal cord. The disease has a predilection for children although any age group can be affected, as was the case of our 78-year-old. Findings include episodes of optic neuritis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, transverse myelitis or other central nervous system manifestations, either alone or in combination.1

There are overlapping features and important differences clinically, radiologically and on cerebrospinal fluid analysis that distinguish MOG antibody-associated disease from multiple sclerosis (MS) and anti-AQP4 neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. According to Dr. Holbrook, the key eye findings are typically bilateral optic nerve head swelling, decreased vision and a wide age range.

“The MRI was very classic in this case with signs of intraorbital nerve inflammation,” he noted. “The confirmative finding was the antibody titer.”

Treatment Solutions

Intravenous Solumedrol (methylprednisolone sodium succinate, Pfizer) was started 1g/day for five days, along with intravenous immunoglobulin 0.5g/kg for four days. Dr. Holbrook initially saw the patient six weeks later. Her vision had gradually improved to 20/40 and 20/100. She showed resolving nerve head swelling, with no hemorrhages noted. Her OCT revealed some restoration of cupping, temporal nerve fiber layer thinning and significant diffuse ganglion cell loss.

“She will be returning for a baseline visual field, and I scheduled her to see a neuro-immunologist (typically, an MS specialist) for probable long-term immunosuppressive therapy with either azathioprine or rituximab,” Dr. Holbrook said.

Dr. Holbrook also advises col-leagues to make these appointments for patients, and if patients need labs or imaging for acute problems, get them done urgently that day.

“The patient and her daughter are both extremely grateful that a timely workup was done,” he said. “Take the time to help expedite treatment; don’t leave anything to the patient.”

When making referrals to the emergency department, give detailed instructions as to what tests to run. Communicate directly with the shift nurse and doctor verbally if you can but definitely in writing, so that they know what the differential diagnosis is.

Dr. Ajamian is board certified by the American Board of Optometry and serves as Center Director of Omni Eye Services of Atlanta. He is vice president of the Georgia State Board of Optometry and general CE chairman of SECO International. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Chen JJ, Flanagan EP, Jitprapaikulsan J, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-positive optic neuritis: clinical characteristics, radiologic clues and outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;195:8-15. |