|

|

Malnutrition in some low-BMI glaucoma patients removes the antioxidant protections conferred by certain vitamins, researchers propose. Photo: Brian D. Fisher, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Although obesity predisposes individuals to numerous systemic health problems, the relationship between weight and risk of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is more complex. In a recent study, researchers investigated associations between body mass index (BMI) and glaucoma in an African ancestry cohort from the Primary Open-Angle African American Glaucoma Genetics study; they found that low BMI increases POAG risk due to nutrient deficiencies and hormonal insufficiencies among some subjects. The team’s paper on the work was recently published in American Journal of Ophthalmology.

A total of 6,634 individuals (2,977 cases and 3,657 controls) were included. Ocular and demographic data were collected from on-site exams, standardized interviews and electronic medical records. BMI was calculated by weight(kg)/height(m)2 and categorized as low (<18.5), moderate (18.5 to 24.9), high (25.0 to 29.9) or very high (≥30).

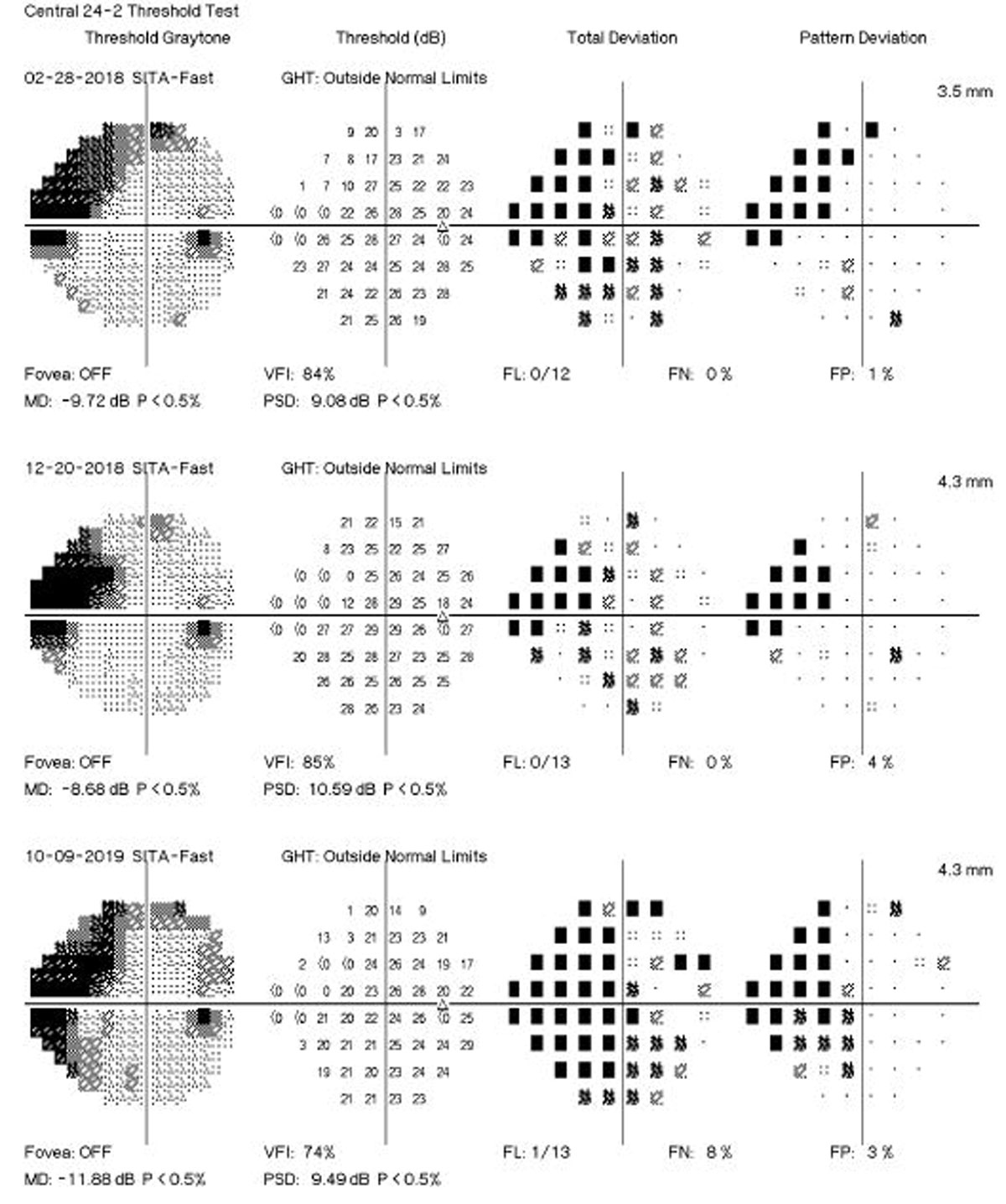

Low BMI was associated with increased POAG risk and subjects were more likely to have larger cup-to-disc (c/d) ratios, worse visual acuity and faster functional progression, indicating more severe glaucoma. This is similar to previous studies that have found a similar relationship between BMI and c/d ratio.

The authors noted that because lower BMI is associated with faster functional progression and other variables that indicate more severe disease, it’s possible those with lower BMI are more likely to require glaucoma surgery.

Additionally, these observations and findings from previous studies support the theory that low BMI increases POAG risk because of a deficiency in vitamins and nutrients that have potential neuroprotective benefits. Specifically, an association between VA and vitamin D insufficiency in POAG was found.

Previous studies have also found that cerebrospinal fluid pressure could be one of the reasons for the correlation between BMI and POAG, as it affects the translaminar pressure gradient, which leads to increased deformation of the lamina cribrosa, decreased neuroretinal rim area and increased visual field defects.

“Another suggested explanation for the negative correlation between BMI and POAG is nutrient intake,” the authors wrote in their AJO paper. “One study proposed that a lack of nutrients in POAG subjects’ diets causes disruptions in regulation (e.g., impaired calcium regulation and oxidative stress) and loss of neuroprotection, as vitamins can act as antioxidants with protective effects.” Another found that higher intake of fruits and vegetables was protective while higher intake of meats and nuts was harmful in oxidative stress–related diseases like glaucoma.

Lastly, an alternative explanation involves hormones. The researchers explain in their paper that activation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptors has been shown to have neuroprotective effects against retinal ganglion cell damage. Because of this, individuals with less body fat—the major site of estrogen production—could be at greater risk for glaucoma, the authors explained.

They acknowledged that these results could have been affected by comorbid conditions common in glaucoma patients, including diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea, which are both associated with high BMI.

“Further research into the relationship between BMI and POAG, as well as a better understanding of the effects of nutrient deficiencies and hormonal insufficiencies on neuroprotection, could provide additional insights into the pathogenesis of POAG,” the authors concluded.

| Click here for journal source. |

Di Rosa I, Halimitabrizi M, Salowe R, et al. Low body mass index poses greater risk of primary open-angle glaucoma in African ancestry individuals. Amer J Ophthalmol. October 16, 2024. [Epub ahead of print.] |