The eyes are one of the biggest markers of facial attractiveness, and everyone has taken notice. The beauty industry is more than happy to aid consumers in enhancing their eyes.1,2 Salon and at-home eyelash augmentation procedures are projected to continue expanding and growing in popularity in the market, and false eyelashes alone are expected to bring in almost two billion dollars by the end of 2024.3,4

The quest for longer, thicker and darker eyelashes and eyes that appear larger, however, does not come without risk. This is a risk many patients don’t mind taking, as they are often unwilling to give up their beauty regimen. In a study of 1,292 women, 44% of participants reported experiencing negative feelings when they weren’t able to wear make-up.5 Even knowing the risks might not be enough for patients to discontinue eye-enhancing procedures. Educating patients about healthier practices and alternatives could be the next best option.

|

| Fig. 1. Magnetic lashes with added mascara. Click image to enlarge. |

False Eyelashes

These are categorized as strip lashes, individual flare lashes and single individual lashes, and are made from real hair or synthetic material. These lashes are applied at the lid margin above the existing lashes with glue, which often contains harsh ingredients with allergenic properties, including formaldehyde and latex. False lashes are associated with allergic contact dermatitis, blepharoconjunctivitis and abrasions secondary to application, removal and lash-fall.6

A newer false eyelash alternative created to avoid glues is the magnetic false eyelash (Figure 1). These lashes can be applied in two ways—either small magnets sandwich a patient’s real lashes between a set of upper and lower false lashes or the magnetic false lashes attach above the lash line to a thick line of metallic-based eyeliner. Risks include application abrasion, lash-fall due to the weight of the magnets and metal allergies in the case of the eyeliner version.

If patients choose to use false eyelashes, recommend that they use glues that do not contain formaldehyde, choose lashes of a natural length—1/3 the eye width to facilitate the best ocular health by maintaining proper aerodynamic flow and avoiding funneling air and debris into the ocular surface—and use partial strips instead of ones that extend the full lash line to avoid using more material than necessary.7 Patients should take breaks in false lash wear or reserve them for special occasions. Placing a small amount of glue or metallic eyeliner on the inside of the wrist for a “patch test” could alert patients to potential allergies before contact dermatitis occurs on their eyelid.

Lash and lid procedures were created to enhance and rarely replace make-up. Mascara is often used in conjunction with false eyelashes to help “blend” them with the real ones. The addition of ocular cosmetics further increases the risk of irritation, allergic reaction and infection. Eye cosmetics themselves can contain allergenic and toxic additives.8-21 The non-profit Environmental Working Group has a free online database that rates more than 70,000 cosmetics and ingredients in terms of safety for doctors and patients alike to learn more about different products.22

|

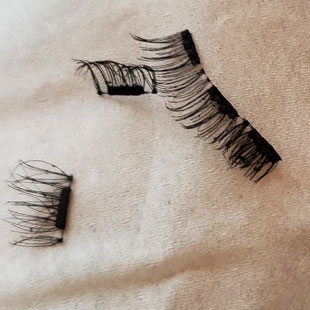

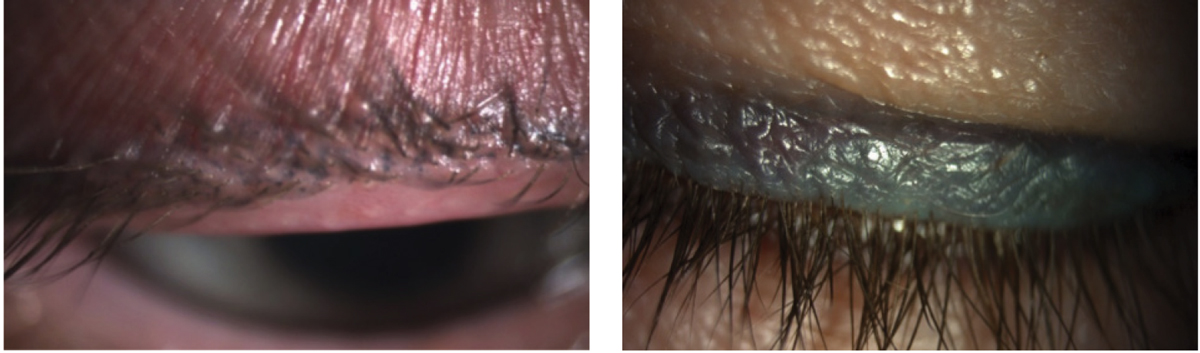

| Fig. 2. During (left) and after (right) an eyelash extension procedure. Note this patient’s ocular irritation post-application. Click image to enlarge. |

Eyelash Extensions

This approach differs from false eyelashes in their application. Extensions are applied by gluing a single hair or synthetic lash to an existing anatomic eyelash (Figure 2). This is a long process and takes a trained esthetician between one and three hours to apply 50 to 200 lash extensions individually with forceps. The glues involved with application contain the same allergenic ingredients as false lashes, sometimes in even stronger concentrations.23,24 Post-application ocular irritation is common.

Most professional estheticians recommend re-doing or “filling” extensions every two to four weeks to replace lashes that have fallen as part of the natural lifecycle of an eyelash—four to 11 months depending on ocular health—and achieve the best look.24 In order to “fill” extensions, old extensions must first be removed. Removal is often achieved by using ocular-irritating glue solvents combined with fragrances. Even in the best case scenario, some of the remover will make its way to the ocular surface, as it would with traditional eye makeup remover.25 A closed eye is not an air- or water-tight seal. Hygiene may become an issue, as these lashes are meant to be worn for weeks at a time. Extensions have the same potential complications as false eyelashes, with added infective risks of chalazia/hordeola and blepharitis.6

Safer practices for eyelash extensions include using glues that do not contain formaldehyde and removers that are oil-based. Patients need to practice lid hygiene and understand that extensions are not like jeans that you don’t wash in an effort to protect the look. Over-the-counter (OTC) hypochlorous acid is a cleaning option that will not dissolve the glues. More natural lash lengths are also preferable.

|

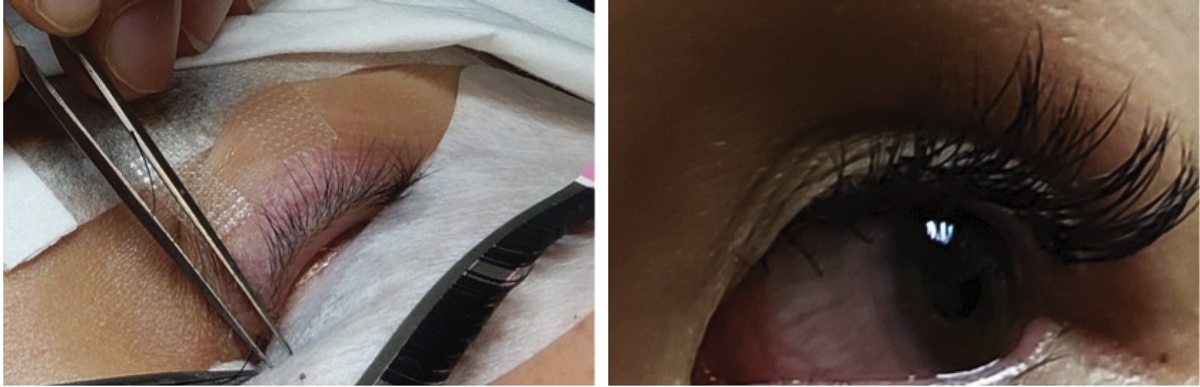

| Fig. 3. Eyelash perming procedure.Click image to enlarge. |

Should you encounter a patient with “extensions gone wrong,” you can remove the extensions quite easily in-office. Start by clearing the lid margins of excess infective debris with an oil-based tea-tree lid cleanser. Next, generously apply a non-irritating oil, such as argan, jojoba, fractionated coconut and macadamia nut, to the lid margin. Have the patient close their eyes for five minutes under a heated micro-bead eye mask. The combination of heat and oil will loosen the glue bonds. You can then use a little mechanical action and jeweler’s forceps to remove the extensions.

If you aren’t able to remove the extensions with these materials, you can obtain online the same lash solvents used by salons. Exercise proper infection and inflammation control with topical steroids and antibiotics as needed and amniotic membranes for corneal involvement.

Eyelash Perming

Sometimes known as a “lash-lift,” lash perming is a trend that may be a bit harder to detect, as there are no false lash materials involved (Figure 3). The only way to know if a patient has undergone a lash-lift is via their case history. The goal with a lash-lift is for the natural eyelashes to curl up and outward.

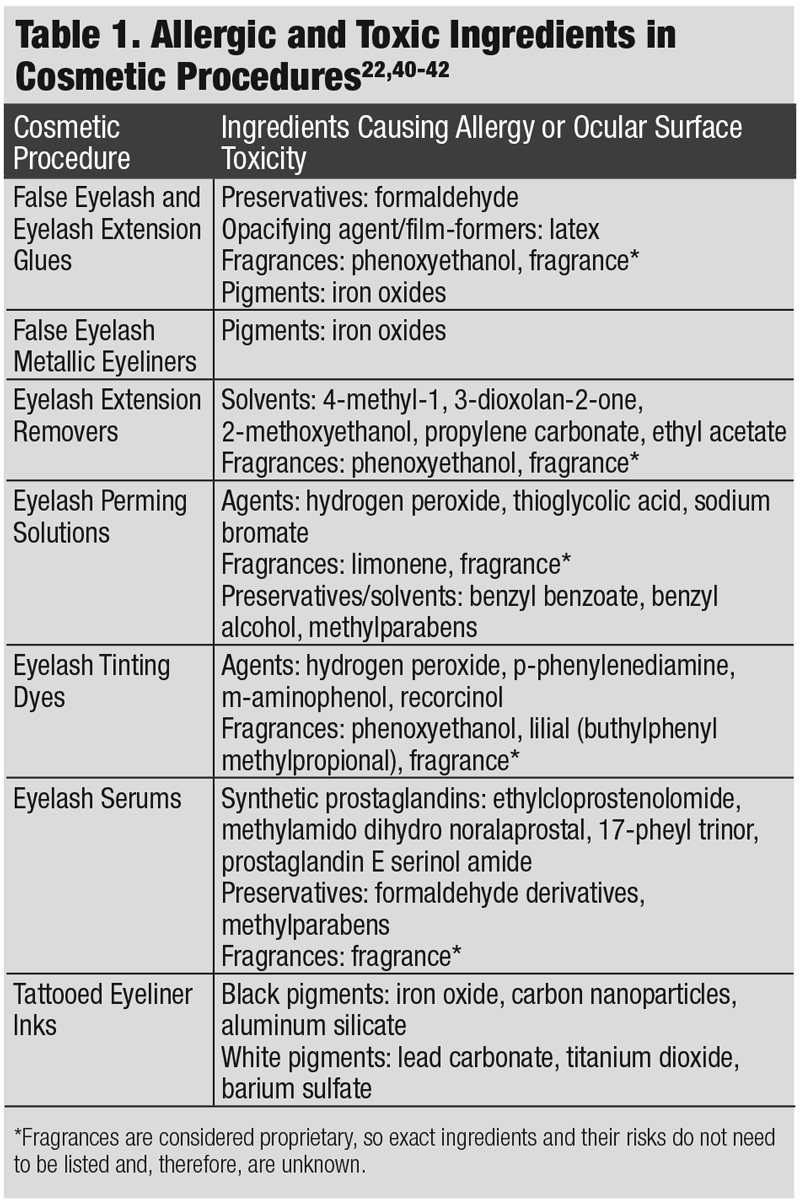

During this procedure, the eyelashes are wrapped around a metallic or plastic rod that either is coated in adhesive or comes with an adhesive for the patient/esthetician to paint on the rod. Some kits use plastic “clips” to keep the lashes in place. Then, perming and neutralizer solutions containing highly ocular toxic active ingredients—hydrogen peroxide and thioglycolic acid—and other irritating additives are applied (Table 1).22 The entire process takes 10 to 15 minutes.

Patients should avoid lash lifting due to the potential risks. However, if a patient is adamant about attempting a lash-lift, only a highly trained professional esthetician should perform this procedure to mitigate the amount of perming and neutralizing solutions on the ocular surface.

The main risk involved in lash lifting is toxic keratoconjunctivitis, and allergic reactions to perming solutions and adhesives are known to occur.22 Patients should see their eye doctor immediately if significant irritation ensues. As water deactivates perming solutions, the patient will likely have been told not to get their lashes wet for 24 hours.26,27 If a patient presents with a reaction within 24 hours, you can flush the ocular surface and lashes. Unfortunately, after that time, these allergens will stick around for the natural lifecycle of an eyelash.24 Patients who experience a “lash-lift gone wrong” will likely need to be treated similarly to patients with basic, mild chemical burns with topical steroids, antibiotics and amniotic membranes.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Eyelash Tinting

In this cosmetic procedure, permanent dyes are applied to darken the eyelashes. Similar to lash perming, the lashes are wrapped around a sticky plastic or metal rod and permanent dye is applied and allowed to set. Ocular toxic and allergenic ingredients commonly found in lash tinting products include hydrogen peroxide, dyes and fragrances. The main risk associated with the procedure is an allergic reaction.28 Again, these allergens will persist for the natural lifecycle of an eyelash.24

Stripping the dye out comes with the risk of permanent damage to the follicle. The best option here is anti-inflammatory control with topical steroids until the lash lifecycle has turned over. Like lash lifting, lash tinting should be avoided, but if a patient is adamant about proceeding, only a highly trained esthetician who is willing to “patch test” prior to the tint should perform the procedure. Lash tinting is often combined with lash lifting, so the risks are twofold, and extra caution should be taken.

While eyelash extensions, perming and tinting are all highly recommended to be done by a licensed esthetician, all the products necessary for patients to self-administer are available online and don’t require a medical or esthetician license. With these lash procedures costing hundreds of dollars, the number of home attempts is high, as is the risk for mistakes.

|

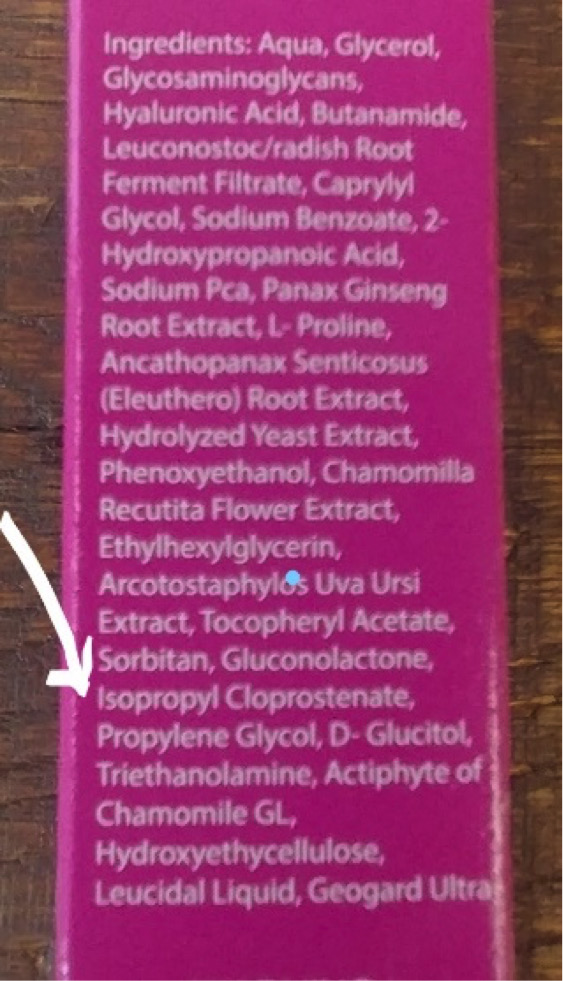

| Fig. 4. One of the most common synthetic prostaglandins is isopropyl cloprostenate. Click image to enlarge. |

Eyelash Serums

When Latisse (bimatoprost 0.03%, Allergan) was first approved by the FDA in 2008, it changed the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries.29 The crucial side effect of darker and thicker eyelashes when this prostaglandin analog was used for glaucoma did not go unnoticed. Daily application along the lash line targets the anagen phase of the eyelash growth cycle, causing longer, thicker and more melanin deposition in the eyelash. This prostaglandin analog may also increase the number of eyelashes in the follicle, cause skin and iris pigmentation, conjunctival hyperemia, pruritus (itching) and lash-loss and lower intraocular pressure.29

OTC eyelash serums have risen in popularity in the beauty industry to compete with Latisse. These OTC options can contain synthetic prostaglandins with identical side effects to the pharmaceutical option. Unlike pharma companies, cosmetic companies are not required to list these potential side effects in their packaging. Synthetic prostaglandins can be difficult to spot unless you are familiar with their common names. The key is to look for “prost” as an indicator of a potential synthetic prostaglandin ingredient (Figure 4). Some OTC lash serums that do not contain synthetic prostaglandins include polypeptide and lipopeptide formulations of amino acids that support eyelash growth.30,31 Even the lipopeptide and polypeptide versions do not necessarily come without risk and may contain other irritating ingredients, so it is important to read the ingredient list.

The healthiest practice for using eyelash serums is to advise patients to choose options that do not include prostaglandins. Any patient using a prostaglandin lash serum should be followed regularly to monitor ocular health. Patients with chronic ocular inflammatory conditions, including dry eye disease, should avoid prostaglandin lash serums.

Case Example: The DIY LiftA 35-year-old Asian female presented with the chief concern of a bilateral eye infection secondary to use of an expired lash perming kit four days prior. She reported bilateral dull-to-sharp eye pain, photophobia, eye and lid redness and mucus discharge that glues her left eye shut overnight. She visited her primary care provider two days ago and was prescribed a topical sulfa-based antibiotic. The antibiotics and artificial tears she was using every hour did not reduce her symptoms. External examination demonstrated scaly, 2+ edema and erythema of the lid margins. Once the mucus was loosened and removed with an oil-based tea-tree lid scrub, a 3+ diffuse keratitis and accompanying conjunctivitis was evident.

The patient had brought her lash perming kit along for inspection. The kit included two tubes—one was a curling cream containing thyioglycolic acid, and the other was a conditioning cream containing hydrogen peroxide—both of which had expired eight months prior to the patient’s purchase and use. She confirmed that while attempting to perm her own eyelashes, she had gotten the contents of both tubes in her eyes. The active ingredients in the lash perming kit were still active, leading to a bilateral toxic keratoconjunctivitis and allergic contact dermatitis. The patient was immediately placed on topical steroids (pred acetate 1%) TID and instructed to use gentle lid scrubs with hypochlorous acid.

She declined a cryopreserved amniotic membrane and was told to avoid all eye cosmetics for the next three days until she could be seen for a follow-up. |

Tattooed Eyeliner

Often referred to as “permanent makeup,” this is a misnomer, as tattooed eyeliner does not last forever. Most tattoos require touch-ups over time as the ink fades. Black eyeliner fades to a bluish tinge, making it easy to detect, and the ink does not always stay contained in the target location, leading to pigment spreading (Figure 5).

The ink used in tattooing is not regulated or necessarily consistent between professional tattoo artists. Black, white and colored inks contain metallic ingredients, which can be allergy-inducing. In addition, tattooing can cause bruising, swelling, infections, scarring, granuloma formation, photo-toxicity and lamellar keratitis.8,9,32-39

|

| Fig. 5. Pigment fade (left) and spread (right), with the tattooed eyeliner extending upward further than the thin line originally applied, of permanent makeup. Both patients have dry eye with MGD. Click image to enlarge. |

A study examining the association between tattoos and meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) found that tattooed patients demonstrated reduced tear break-up time, loss of meibomian gland architecture and increased corneal staining.32 The impact of the concussive damage and chemical toxicity is also theorized to be contributory to MGD. Permanent makeup on the eyelid should be avoided, as this is not a procedure that can be reversed.

As eye care practitioners, we are well poised to recognize the complications stemming from dangerous beauty trends involving the ocular surface and adnexa. With the cosmetic industry doing everything it can to promote the growth of eyelash and lid enhancement, we need to educate patients about healthier practices and alternatives to strike a better balance between health and beauty.

Dr. Doll is an assistant professor of optometry and the coordinator at Pacific Dry Eye Solutions, a dry eye center of excellence within the Pacific University College of Optometry. She coordinates clinical and didactic ocular surface dryness education, including a course devoted to advanced ocular surface dryness disease clinical techniques, and lectures nationally on ocular surface dryness.

| 1. Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, et al. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2003;25(4):199-205. 2. McCurdy JA Jr. Beautiful eyes: characteristics and application to aesthetic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2006;22(3):204-14. 3. Crawford SK. ABC News. How false eyelashes have become a must-have, everyday accessory and a booming market. abcnews.go.com/Lifestyle/false-eyelashes-everyday-accessory-booming-market/story?id=55019597. May 8, 2018. Accessed September 17, 2019. 4. Market Research Future. False eyelashes market research report-global forecast till 2024. www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/false-eyelashes-market-2921. July 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019. 5. Cison PR Newswire. New survey results indicate there’s more to makeup use than meets the eye. www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-survey-results-indicate-theres-more-to-makeup-use-than-meets-the-eye-140012233.html. February 22, 2012. Accessed September 17, 2019. 6. Amano Y, Sugimoto Y, Sugita M. Ocular disorders due to eyelash extensions. Cornea. 2012;31(2):121-5. 7. Amador GJ, Mao W, DeMercurio P, et al. Eyelashes divert airflow to protect the eye. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(105):20141294. 8. Adams RM, Maibach HI. A five-year study of cosmetic reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(6):1062-9. 9. Meynadier JM, Meynadier J, Mark Y. True cosmetic-induced dermatitis. In: Baran R, Maibach HI, 1st ed. Textbook of Cosmetic Dermatology. London, UK, Martin Dunitz, 1994:551-6. 10. Dawson NL, Reinhardt DJ. Microbial flora of in-use, display eye shadow testers and bacterial challenges of unused eye shadows. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42(2):297-302. 11. Pack LD, Wickham MG, Enloe RA, et al. Microbial contamination associated with mascara use. Optometry. 2008;79(10):587-93. 12. Wilson LA, Julian AJ, Ahearn DG. The survival and growth of microorganisms in mascara during use. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79(4):596-601. 13. Lundov MD, Moesby L, Zachariae C, et al. Contamination versus preservation of cosmetics: a review on legislation, usage, infections, and contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60(2):70-8. 14. Steinberg DC. 2010 frequency of preservative use. Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2010;125:46-51. 15. De Groot AC, Flyvholm MA, Lensen G, et al. Formaldehyde-releasers: relationship to formaldehyde contact allergy. Contact allergy to formaldehyde and inventory of formaldehyde-releasers. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61(2):63-85. 16. Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(4):424-30. 17. Orecchinoi AM. Eye make-up. In: Baran R, Maibach HI, eds. Cosmetic. Dermatology. London, UK, Martin Dunitz, 1994:143-9. 18. Hunter M, Bhola R, Yappert MC, et al. Pilot study of the influence of eyeliner cosmetics on the molecular structure of human meibum. Ophthalmic Res. 2015;53(3):131-5. 19. Lodén M, Wessman C. Mascaras may cause irritant contact dermatitis. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2002;24(5):281-5. 20. Draelos ZD. Eyelash cosmetics. In: Cosmetics in Dermatology. New York, NY, Churchill Livingstone, 1995:41-52. 21. O’Donoghue MN. Eye cosmetics. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:633-9. 22. EWG’s Skin Deep Cosmetics Database. www.ewg.org/skindeep. September 17, 2019. 23. Winks Eyelash Boutique. The truth about unlimited lash sets. winksboutique.com/how-many-lashes-are-in-a-full-set-of-extensions. February 19, 2018. Accessed September 17, 2019. 24. Aumond S, Bitton E. The eyelash follicle features and anomalies: a review. J Optom. 2018;11(4):211-22. 25. Debbasch C, Ebenhahn C, Dami N, et al. Eye irritation of low-irritant cosmetic formulations: correlation of in vitro results with clinical data and product composition. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43(1):155-65. 26. Rodulfo K. Elle. Everything you need to know about lash lifts (and why they’re better than lash extensions). www.elle.com/beauty/makeup-skin-care/a19409536/what-is-lash-lift. March 13, 2018. Accessed September 17, 2019. 27. Mychaskiw M. This treatment gives you mega lashes without extensions. InStyle. www.instyle.com/beauty/lash-lift-treatment-curled-eyelashes. October 6, 2017. Accessed September 17, 2019. 28. Vogel TA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar, MLA. Allergic contact dermatitis presenting as severe and persistent blepharoconjunctivitis and centrofacial oedema after dyeing of eyelashes. Contact Dermatitis, 2014;71(5):304-6. 29. Allergan. Latisse (bimatoprost ophthalmic solution) 0.03% package insert. www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/latisse_pi.pdf. July 2017. Accessed September 17, 2019. 30. Pyo HK, Yoo HG, Won CH, et al. The effect of tripeptide-copper complex on human hair growth in vitro. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30(7):834-9. 31. Iwabuchi T, Takeda S, Yamanishi H, et al. The topical penta-peptide Gly-Pro-Ile-Gly-Ser increases the proportion of thick hair in Japanese men with androgenetic alopecia. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15(2):176-84. 32. Lee YB, Kim JJ, Hyon JY, et al. Eyelid tattooing induces meibomian gland loss and tear film instability. Cornea. 2015;34(7):750-5. 33. Bee CR, Steele EA, White KP, et al. Tattoo granuloma of the eyelid mimicking carcinoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(1):e15-7. 34. Peters NT, Conn H, Côté MA. Extensive lower eyelid pigment spread after blepharopigmentation. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;15(6):445-7. 35. Hurwitz JJ, Brownstein S, Mishkin SK. Histopathological findings in blepharopigmentation (eyelid tattoo). Can J Ophthalmol. 1988;23(6):267-9. 36. Goldman A, Wollina U. Severe unexpected adverse effects after permanent eye makeup and their management by Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1305-9. 37. ThoughtCo. Helmenstine AM. Tattoo ink chemistry. www.thoughtco.com/tattoo-ink-chemistry-606170. September 13, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019. 38. Lu CW, Liu XF, Zhou DD, et al. Bilateral diffuse lamellar keratitis triggered by permanent eyeliner tattoo treatment: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(1):283-5. 39. Schwarze HP, Giordano-Labadie F, Loche F, et al. Delayed-hypersensitivity granulomatous reaction induced by blepharopigmentation with aluminum-silicate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(5 Pt 2):888-91. 40. Hazard. 2-Methoxyethanol. hazard.com/msds/mf/baker/baker/files/m2327.htm. Accessed September 17, 2019. 41. PubChem. (S)-4-Methyl-1,3-dioxolan-2-one. pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/S_-4-Methyl-1_3-dioxolan-2-one. Accessed September 17, 2019. 42. Toxnet. Hazardous substance data bank (HSDB). toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/hsdb.htm. Accessed September 17, 2019. |