|

Infectious keratitis—a common cause of visual impairment—occurs when the cornea’s integrity is compromised by a bacteria, fungus, virus or parasite. In the United States and other developed countries, these infections are typically associated with contact lens use or poor lid hygiene.1 Ocular trauma involving vegetative or organic matter is more common in underdeveloped areas.1-3 Identifying the causative microorganism in a case of infectious keratitis is essential for initiating the most efficacious topical treatment and eventual resolution of the infection.

Here we review the differential diagnoses of the different kinds of infectious keratitis and treatment options through a real-world case example.

|

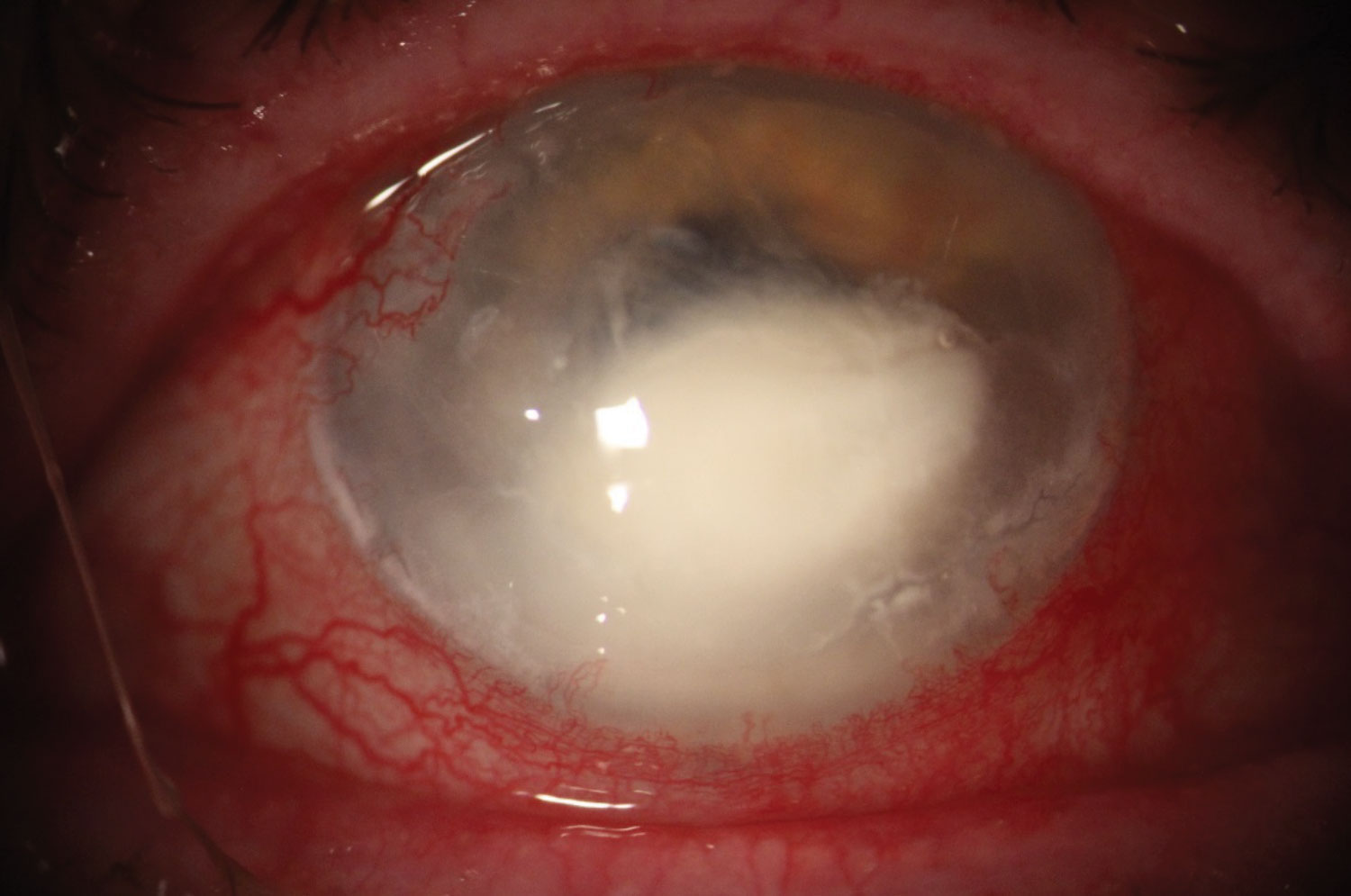

| This image shows a bacterial ulcer caused by the gram-negative rod Serratia marcescens. Click image to enlarge. |

Patient History

A 51-year-old Caucasian female presented with a painful, photophobic right eye. She had a history of extended soft contact lens wear and denied any previous incidence of trauma. One week prior, an optometrist had diagnosed her with a corneal ulcer of unknown etiology and initiated treatment with Tobradex ST (tobramycin and dexamethasone, Eyevance). After an exacerbation of symptoms and a second local opinion, the patient was referred to our clinic for further evaluation.

At her initial visit, her best-corrected visual acuities (BCVA) were 20/50 OD and 20/25 OS. Slit lamp examination of the right eye revealed a 1.5mm by 1.5mm epithelial defect overlying a similarly sized infiltrate. The anterior chamber contained few rare cells, but no hypopyon was noted. Pupils, extraocular motility and intraocular pressures (IOP) were normal. Clinical examination of the left eye was unremarkable.

We diagnosed the patient with a presumed bacterial central corneal ulcer and determined it was likely related to soft contact lens wear based on the patient’s case history. We decided to hold off on culturing because the ulcer had already been treated with antibiotics. At her initial visit with us, the patient was using Vigamox (moxifloxacin, Novartis) four times a day in her right eye. We increased her dosage to once every hour around the clock and expressed the importance of monitoring the condition closely over the next few days.

On follow up, the BCVA of her right eye had reduced to 20/500. Slit lamp examination of the right eye showed that the infiltrate had nearly doubled in size with the overlying epithelial defect measuring 3mm by 3mm. Diffuse corneal edema was now surrounding the central lesion. We performed a corneal culture and prescribed fortified tobramycin along with fortified cefazolin to be alternated every hour around the clock. The patient was asked to return in 24 hours.

|

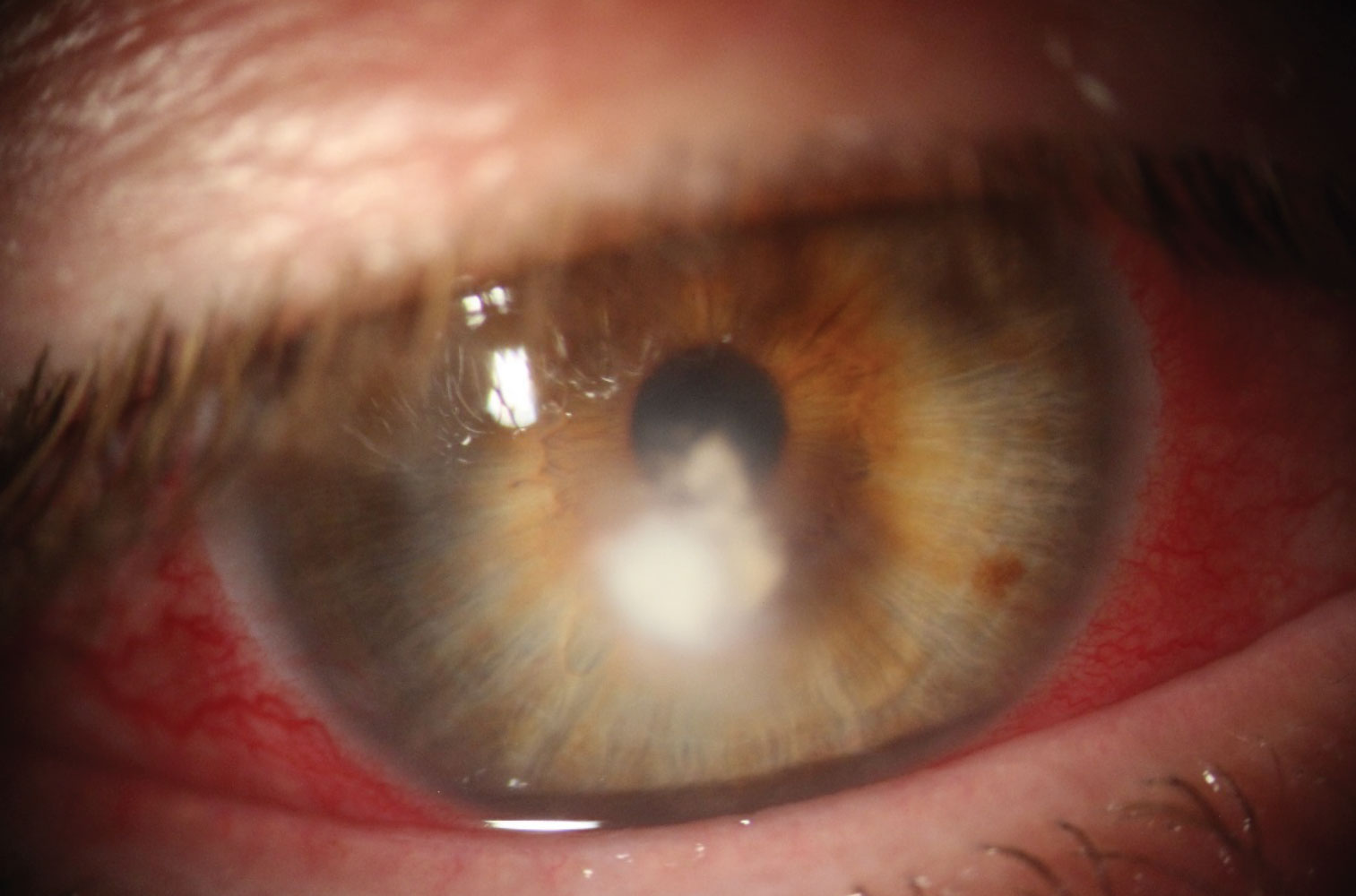

| The feather-like borders of this lesion are indicative of a fungal ulcer. Click image to enlarge. |

Searching for a Cause

Being the most common etiology of infectious keratitis, bacterial ulcers are most often related to contact lens use.1,3 These ulcers typically present with well-defined, dense infiltrates that coincide with similarly sized epithelial defects. Extensive conjunctival injection, mucopurulent discharge and an anterior chamber reaction are common signs.

On the contrary, fungal keratitis typically presents with a feather-like infiltrate with poorly defined borders. These infiltrates may have overlying epithelial defects; however, it is not uncommon for fungal infections to have closed or even heaped epithelium overlying the infiltrate. Satellite lesions located around the main lesion are also a good indication of possible fungal etiology.2

For our patient, the case history did not align with a typical fungal onset. A clinical red flag occurred when her condition remained unresponsive to aggressive, broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment alone. The culture results confirmed some type of fungal etiology, but the exact microorganism could not be identified at first. Due to the patient’s location, she was unable to locally fill a prescription for Natacyn (natamycin, Eyevance), so we started fortified voriconazole therapy as an alternative.

|

| This cornea shows a central depressed opacity after the resolution of a fungal ulcer. Note the scleral lens. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnostic Techniques

Corneal culture should be performed when the infected area is large (>1mm to 2mm), centrally located and worsens after initial treatment. Sabouraud’s agar and fungal smear microscope slides are best at demonstrating fungal growth, while blood and chocolate agar are typically used for bacteria. Gram stains are also helpful in determining bacterial causes.

Avoiding the eyelids and eyelashes while performing a culture will decrease the risk of potential contamination. If the epithelium is closed, debridement is recommended to access the infiltrative area where active invasion is occurring.1-5 Research shows that infectious keratitis should be treated as bacterial until a fungal etiology can be confirmed.2,3 Primary reasoning supporting this approach is due to the high toxicity of topical antifungal agents to the cornea.

Currently, the only topical antifungal commercially available is Natacyn. Any other topical antifungal must be made by a compounding pharmacy. Sometimes geographic location, cost and limited resources make obtaining appropriate medications challenging.

Knowing the type of microorganism that caused the infection is critical in prescribing the most effective treatment.3 According to the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial (MUTT) I, natamycin was more efficacious in treating filamentous fungal keratitis, particularly Fusarium, over topical voriconazole.6 Amphotericin B is another compounded alternative treatment that is beneficial in treating keratitis caused by Candida.5 Oral antifungals like voriconazole may be added as adjunctive therapy; however, the MUTT II trial determined that it is not a superior alternative for faster resolution.7

After four months of topical antifungal treatment, copious artificial tears and a lot of patience, our patient’s fungal infection resolved. On final examination, a large depressed central corneal opacity remained. After a specialty contact lens fitting, our patient’s BCVA was 20/20 with her scleral lens and she was pleased with her vision. Although infectious keratitis seems daunting at first, careful case history and proper corneal culturing are the most simple and important aspects to guide the management of infectious keratitis.

Dr. Delaney Kent completed a residency in refractive surgery and ocular disease at Vance Thompson Vision in South Dakota. She currently practices at Chu Vision Institute in Bloomington, MN.

1. Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmol. 2017;124(11):1678-89. 2. Tanure MA, Cohen EJ, Sudesh S, et al. Spectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cornea. 2000;19:307-12. 3. Ray KJ, Prajna L, Srinivasan M, et al. Fluoroquinolone treatment and susceptibility of isolates from bacterial keratitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(3):310-3. 4. Alfonso EC, Rosa RH. Fungal keratitis. In Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea and external diseases: clinical diagnosis and management. St Louis: Mosby, 1997:1253-66. 5. O’Day, D.M., Head, W.S., Robinson, R.D., and Clanton, J.A. Corneal penetration of topical amphotericin B and natamycin. Curr Eye Res. 1986;5:877-82. 2. Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Mascarenhas J, et al. The mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs. voriconazole. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:422-9. 3. Prajna NV, Krishnan T, Rajaraman R, et al. Adjunctive Oral Voriconazole Treatment of Fusarium Keratitis: A Secondary Analysis From the Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial II. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(6):520-5. 8. Deorukhkar S, Katiyar R, Saini S. Epidemiological features and laboratory results of bacterial and fungal keratitis: a five year study at a rural tertiary-care hospital in western Maharashtra, India. Singapore Med J. 2012;53:264-67. |