|

The vast majority of refractive surgery cases go according to plan, but when patients do experience complications, optometrists are there to play an integral role in comanagement. Corneal melting, or keratolysis, is one such complication that may occur after LASIK. It can lead to scarring, irregular astigmatism, photophobia and decreased vision. Improvements in surgical techniques and technology have reduced the incidence of postoperative complications after LASIK, but corneal melt remains an emergent threat to a patient’s vision. Prompt recognition and aggressive treatment can prevent permanent visual loss. In this column, we review the pathophysiology and treatment of this potentially vision-threatening condition.

Pathophysiology

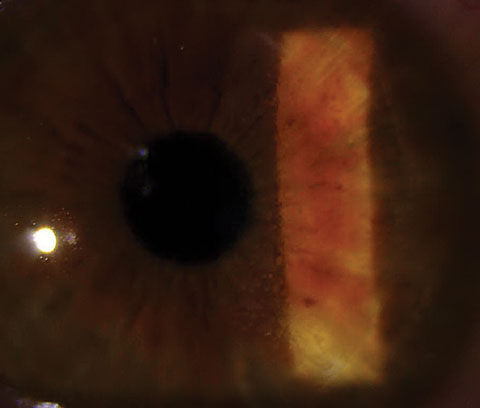

The incidence of a corneal melt following LASIK is difficult to quantify accurately, as reports in published literature are often small series or case reports discussing a single event.1 The melting process often starts at the rim of the flap and is commonly associated with a variety of conditions, such as epithelial ingrowth.1 The migration of epithelial cells under the LASIK flap increases following enhancement surgery, specifically following lifting of the flap.1,2 Patients with certain preexisting corneal conditions present a greater risk of developing ingrowth and are at a greater risk for corneal melting after LASIK flap creation (Figure 1).3,4 These conditions include epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, collagen vascular diseases and autoimmune diseases.3,4 Additionally, dry eye disease creates a poor healing environment of the cornea, which may potentially make corneal melt more likely. These conditions should be resolved before LASIK surgery is performed.

Topical NSAIDs are commonly used for reduction of postoperative inflammation following ocular surgeries. NSAIDs have been associated with corneal toxicity, which is believed to be associated with corneal melting.5,6

|

| Fig. 1. This patient’s corneal condition put him at greater risk for the corneal melt he eventually developed. |

Diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK), which is characterized by diffuse infiltrates at the flap margin, can lead to pain, photophobia, blurred vision and, eventually, corneal melting. Clinically, patients with DLK will present with progressive hyperopia and irregular astigmatism. The stages of DLK, based on clinical appearance relative to the intensity of inflammation, are broken down as follows:7

• Stage I includes an infiltrate in the periphery of the flap.

• Stage II is when the infiltrate involves the periphery and visual axis.

• Stage III is identified by a cluster of inflammatory cells in the central cornea.

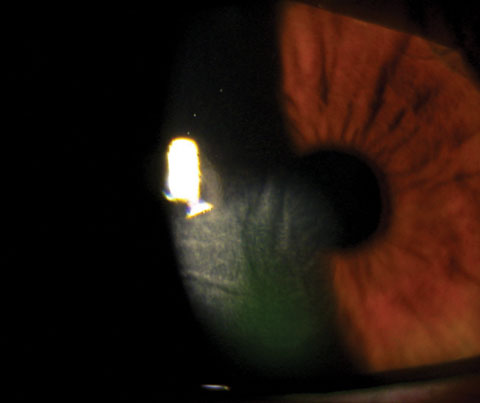

• Stage IV is severe inflammation and the beginning of corneal melting, followed by corneal scarring, loss of visual acuity and irregular astigmatism (Figure 2).

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to remove the agent contributing to the corneal melt process. The cause can be multifactorial and will demand a variable approach.

One approach to treatment is observation only. If the corneal melt is not progressing or causing visual complications, the process may be self-limiting.1 Obtaining accurate slit lamp photographs of the corneal melt will aid in deciding if progression is occurring. If the condition progresses or causes degradation in vision, surgical intervention may be necessary.

|

| Fig. 2. Stage IV inflammation is the most severe DLK classification and shows the beginning of corneal melt. |

Epithelial ingrowth can be aggressive, so the need for treatment is immediate. Since it is more common following LASIK, these patients require careful observation. If the epithelial ingrowth involves 30% of the flap, or is associated with corneal melting proven by clinical or topographical examination, consider treatment.8 If a patient is having changes in vision or if topographical changes are noted, consider surgical intervention. The general procedure for removing epithelial ingrowth requires a surgeon to lift the flap and scrape the epithelial cells from the stromal bed and undersurface of the flap.2,9-11 At the conclusion of the procedure, a bandage contact lens is typically placed and the patient is started on topical antibiotics and steroids.

Other treatments, such as ethanol, mitomycin and phototherapeutic keratectomy, have been suggested for epithelial ingrowth, but adverse events are possible.2,8,10,12 These should all be considered secondary options, if the risk associated with scraping is too great.

DLK treatment in the early stages (I or II) involves a topical steroid to reduce the inflammatory event and decrease the likelihood of a corneal melt process. If a patient presents with advanced stage III or IV DLK, surgical intervention of lifting the LASIK flap, cleaning the interface, and treatment with both a topical corticosteroid and an antibiotic will be necessary.

A Corneal Melt Case ReportA 28-year-old female presented to clinic urgently with a complaint of an irritated right eye for about three days. Her ocular history was significant for LASIK in both eyes in 2012, and a LASIK enhancement in the right eye in 2015. Her general medical history was unremarkable. Visual acuity uncorrected was 20/40 OD and pinhole visual acuity was 20/20 OD. Examination of the anterior segment identified a small amount of epithelial ingrowth superior to the nasal, along the flap edge, as well as an inferior temporal corneal melt along the flap edge with a small amount of epithelial ingrowth present. Treatment options discussed with the patient included lifting the flap and removing the epithelial ingrowth or, a more conservative approach, aggressive ocular surface treatment with close observation. Ultimately, an initial conservative approach was decided on and a treatment of topical corticosteroid, topical cyclosporine, punctal plugs and preservative artificial tears was initiated. The patient was monitored on a weekly basis for six weeks. No changes of the epithelial ingrowth or corneal melt were noted. Her vision improved from 20/40 OD uncorrected to 20/20 OD uncorrected after six weeks. The foreign body sensation resolved and the patient was tapered off the topical steroid. Topical cyclosporine was continued and no changes of the cornea melt process or epithelial ingrowth has been noted in four months. |

Before treating post-LASIK patients who have autoimmune disorders, corneal dystrophies or dry eye syndrome—all conditions that can lead to a corneal melt or have led to a corneal melt episode—you must address the underlying condition first. This may involve consultation with the patient’s rheumatologist in regards to more specifically targeted control of the patient’s autoimmune disorder. In the case of dry eye syndrome and other corneal ocular surface diseases, treatment may include artificial tears, punctal plugs, topical cyclosporine drops, topical corticosteroid drops, autologous serum topical drops, meibomian gland dysfunction treatment or the use of amniotic membrane grafts.

Corneal melting following LASIK is a significant complication that requires prompt recognition. A detailed preoperative examination for refractive surgery patients is necessary to identify underlying systemic and ocular conditions that can predispose a patient to a corneal melt process. Patients who have undergone refractive surgery and have conditions that predispose them to corneal melting should have close follow up. Early identification and prompt treatment can prevent permanent vision loss from this rare but serious refractive complication.

Dr. Schweitzer is a cornea, glaucoma, cataract and refractive surgery specialist at Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, SD.

|

1. Guell J, Gris O, Gaytan J, Marero F. Melting. In: Alió JL, Azar DT, eds. Management of Complications in Refractive Surgery. New York:Springer;2008. 2. Wang M, Maloney R. Epithelial ingrowth after laser in situ keratomileusis. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;129:746–51. 3. Dastgheib K, Clinch T, Manche E, et al. Sloughing of corneal epithelium and wound healing complications associated with laser in situ keratomileusis in patients with epithelial basement membrane dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 2000 Sep;130(3):297-303. 4. Seiler T, Wollensak J. Myopic photorefractivekeratectomy with the excimer laser. One-year follow- up. Ophthalmology 1991;98(8):1156–63. 5. Congdon N, Schein O, von Kulajta P, et al. Corneal complications associated with topical ophthalmic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Cataract Refract Surg 2001;27(4):622–31. 6. Flach A. Corneal melts associated with topically applied non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2001;99:205–12. 7. Linebarger E, Hardten D, Lindstrom R. Diffuse lamellar keratitis: diagnosis and management. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26(7):1072–7. 8. Haw W, Manche E. Treatment of progressive or recurrent epithelial ingrowth with ethanol fol- lowing laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2001;17(1):63–8. 9. Walker M, Wilson S. Incidence and prevention of epithelial growth within the interface after laser in situ keratomileusis. Cornea. 2000 Mar;19(2):170-3. 10. Helena M, Meisler D, Wilson S. Epithelial growth within the lamellar interface after laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) Cornea. 1997 May;16(3):300-5. 11. Lahners W, Hardten D, Lindstrom R. Alcohol and mechanical scraping for epithelial in-growth following laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2005 Mar-Apr;21(2):148-51. 12. Vroman D, Karp C. Complication from use of alcohol to treat epithelial ingrowth after laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001 Sep;119(9):1378-9. |