|

Second-guessing another doctor’s clinical care should not be taken lightly, but if you do, be judicious in your approach. Here are several takeaways from when I found myself in this position.

Case

I was examining a 55-year-old Caucasian female a couple of weeks ago. During the evaluation, she mentioned her mother and how hard of a time she was having with her glaucoma. Alarm bells went off in my head while she was giving me her version of events. We should always take a secondhand impression of events with a grain of salt, but there were several items mentioned that were, unfortunately, all too familiar. One thing led to another and I agreed to see the patient’s mother for a second opinion.

|

|

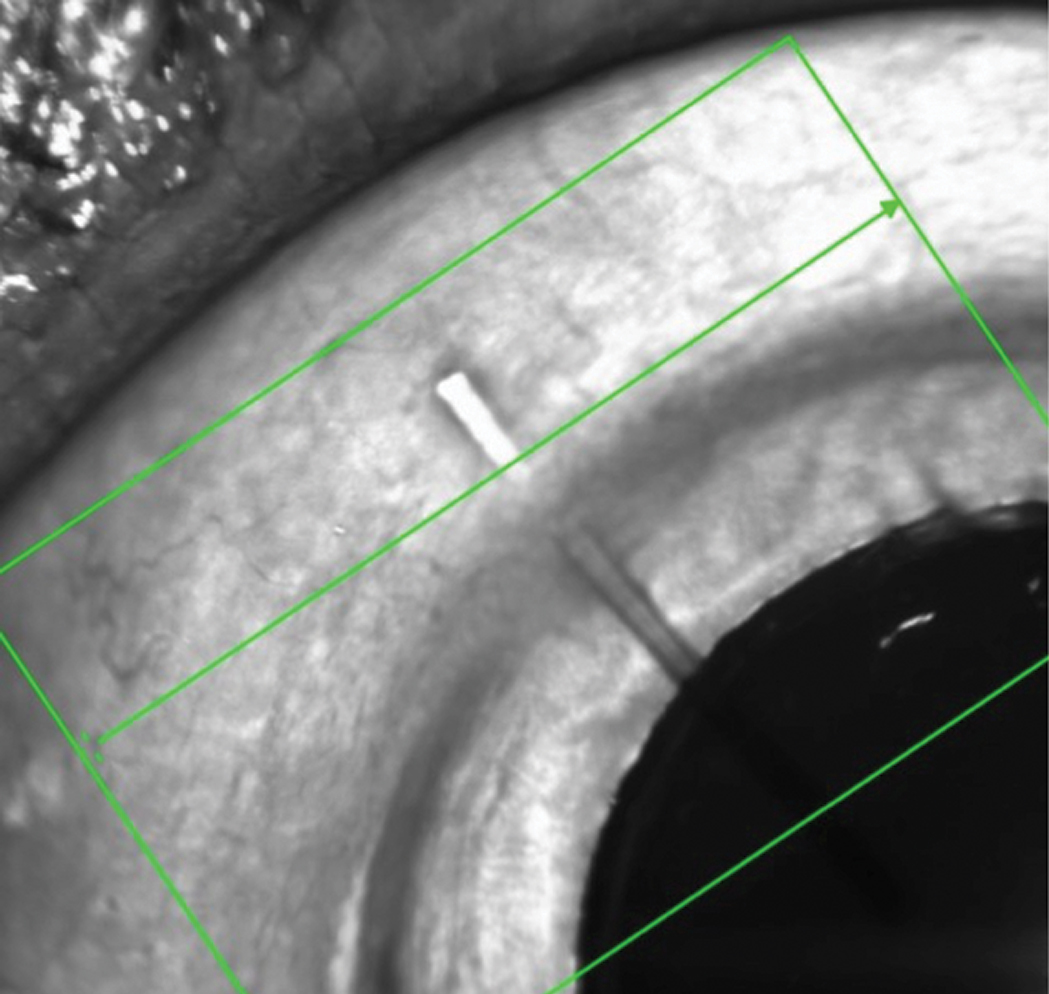

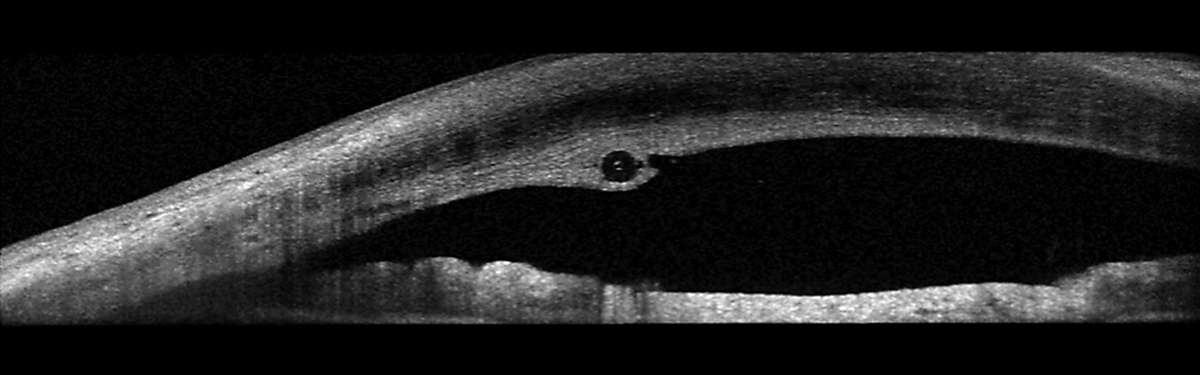

This MIGS device is designed to facilitate drainage of aqueous from the anterior chamber into the subconjunctival space. Click image to enlarge. |

She was an 81-year-old woman who presented anxiously about her “failed glaucoma surgery” in her left eye. She had been treated for approximately 10 years for bilateral glaucoma, which she reported was now well controlled with daily Rhopressa (netarsudil, Aerie). After moving to the area, she noted a decline in vision in the left eye and sought the care of a local OD who immediately referred her to a glaucoma surgeon. The surgeon changed her glaucoma medications and scheduled her for surgery the following week. Post-op, the patient was told the procedure had failed, there was some bleeding and there was nothing more that could be done. After her third follow-up, she sought my care.

At her first visit with me at the end of April, entering visual acuities were 20/25 OD and 20/200 OS. Best-corrected acuities were 20/25+ OD and 20/80 OS. Pupils were round, equal and without an afferent pupillary defect, and extraocular muscles were full in all positions of gaze. Current medications included Xelpros (latanoprost, Sun Pharma) QHS OU, Cosopt (dorzolamide/timolol, Akorn) TID OU and prednisolone acetate QD OS, along with oral diazepam, trazodone and prednisone. She reported an allergy to indomethacin.

Slit lamp examination of her anterior segments was remarkable for bilateral LASIK flaps, with a clear interface and no striae or epithelial ingrowth bilaterally. She had undergone LASIK approximately 15 years earlier. Pachymetry readings were 522µm OD and 557µm OS. Applanation tensions at 11:06am were 12mm Hg OD and 10mm Hg OS. There were scattered guttatae, and the patient was pseudophakic bilaterally. She’d had cataract surgery about seven years earlier.

In the right eye, there was a tube in the anterior chamber extending to the visual axis on one end, and to about 2mm behind the limbus and beneath the conjunctiva at the other. There was no valve present, nor was the tube cut from a valve that had failed. Close examination of the conjunctiva distal to the tube demonstrated no explanted valve or disrupted conjunctiva. There was no bleb.

The patient was dilated in the usual fashion. Through dilated pupils, her intraocular lenses were clear and centered in their capsular bags. The posterior capsules were clear and intact OU. Bilateral posterior vitreous detachments were present. Posterior pole imaging demonstrated bilateral tilted discs with peripapillary atrophy and myopic stretching. The left disc was tilted much more than the right, and consequently, both cup-to-disc appearances were vertically elongated due to the oblique nasal insertion of the optic nerves OS>OD.

|

|

The patient’s left eye demonstrated an oblique insertion of the optic nerve, along with macular changes and thinning of the neuroretinal rim. Click image to enlarge. |

There was concurrent glaucomatous damage present OU. But my initial impression was that, although damage from glaucoma was evident, neither nerve was at the threshold of complete neuroretinal rim loss. Prior to her LASIK surgery, the patient said she was a -9.00 OU myope. This would certainly account for her myopic optic nerve characteristics.

The right macula was characterized by fine retinal pigment epithelial mottling; that of the left was characterized by more advanced retinal pigment epithelial disruption as well as scattered drusen. Given the symmetric pre-LASIK refractive error and the lack of myopic stretching in the right eye, it is possible that some of the macular changes in her left eye were related to myopic stretching. When asked if she was told about the changes in her maculae, OS>OD, she looked surprised and said no.

The retinal vascular examination was essentially unremarkable, except for expected mild arteriolar changes associated with her age. Her peripheral retinal evaluations were remarkable for 360° cystoid and scattered areas of pavingstone degeneration. I obtained optic nerve images and anterior segment OCTs of the tube/shunt.

|

|

The stent was improperly placed. Here, it runs through the cornea, anterior to the anterior chamber angle. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Examining this patient raised a few questions and brought home several points. First, the patient sought care due to decreased vision OS. Was her vision decreased because of progressive field loss secondary to the glaucoma? Or, was it decreased due to progression of the macular changes in the left eye? The only way to determine the answer prior to glaucoma surgery would have been through completing a visual field study and assessing previous records, neither of which was done.

Second, we must be careful about abruptly changing the meds of a new patient who had been managed by another provider for years beforehand. Obtaining prior records helps tremendously in determining what, if anything, needs to be done differently. Our patient may not have required a medication change. At the very least, the efficacy of the change should have been evaluated prior to surgery. It is certainly possible that her glaucoma was completely stable and her vision changes were related to her macular issues instead. But in any event, the glaucoma surgeon didn’t think twice about proceeding with surgery.

The device implanted was a Xen Gel Stent (Allergan), which is a flexible stent inserted perpendicular to and through the angle and extends into the subconjunctival space. It works to reduce intraocular pressure by facilitating aqueous movement out of the anterior chamber and into the subconjunctival space, similar to a trabeculectomy. The problem is, the stent was not properly placed in this patient, who may not have even needed it in the first place.

Takeaways

It’s important to avoid throwing another provider under the bus; instead, give them the benefit of the doubt. However, when a provider actively works against optometry in scope expansion issues, citing our inability to properly manage glaucoma, and leaves a trail of excessive and unnecessary surgeries in multiple patients over years, you begin to realize that involving this provider in your patients’ care is not in their best interest.

We as ODs can and should facilitate better glaucoma care by becoming more active in patient management, as opposed to immediately referring to a glaucoma surgeon. Lean on the ODs in your area who manage glaucoma for help, if needed, as most glaucoma patients do not require surgery. Becoming more involved in patient care can reduce unnecessary referrals that may ultimately end up doing more harm than good, as well as improve overall outcomes.

Dr. Fanelli is in private practice in North Carolina and is the founder and director of the Cape Fear Eye Institute in Wilmington, NC. He is chairman of the EyeSki Optometric Conference and the CE in Italy/Europe Conference. He is an adjunct faculty member of PCO, Western U and UAB School of Optometry. He is on advisory boards for Heidelberg Engineering and Glaukos.