Scope Expansion SeriesRead the other articles featured in this series:

|

Scope of practice gains continue across the country, allowing a growing number of optometrists to expand the level of care they provide. As discussed in the first article of this four-part series on scope expansion—“Bringing Incisions and Injections to Your Clinic,” featured in our May issue—having the option to practice to the full extent of their clinical abilities is crucial not just for ODs but also for the patients they serve. One new, high-profile responsibility being advocated for is allowing optometrists to perform laser procedures, including YAG capsulotomy, selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) and laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI). Fortunately, in recent years, several states have reached success in their legislative battles to get a laser bill passed, including Alaska (2017), Arkansas (2019), Mississippi (2021), Wyoming (2021) and most recently Virginia and Colorado (2022).

“As a profession, we have come a long way,” notes Nate Lighthizer, OD, associate dean at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry, a longtime laser-use advocate and educator. “At the time of my residency in 2009, Oklahoma was the only state that allowed laser privileges for optometrists. As we sit here today, there are currently nine states where optometrists have laser authority. This is a clear indication of the progress that has been made and the expansion we will continue to see moving forward.”

As this momentum continues and more ODs gain the ability to perform laser procedures, it is important that you and your practice are prepared to offer these services to your patients. In this article, the second in our scope expansion series, we delve into the logistics of implementation and practical tips for success.

Setting Up for Success

As with any new service, there are logistical considerations to address when integrating laser procedures into clinical practice. These include determining if any additional education or certification is needed, purchasing the necessary tools and staff training, to name a few.

Specific education, training and certification requirements will vary state by state, so it lies on your shoulders as the OD to confirm which procedures are allowed under the legislation in your practicing state and which rules and regulations are in place. It’s also important to find out what is required in your state for an OD to maintain the necessary licensure and certification.

|

|

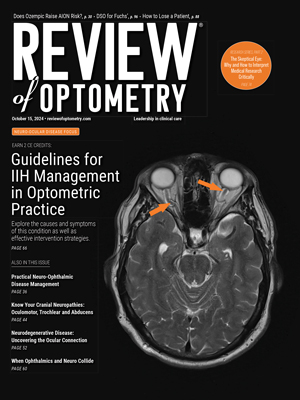

A patient after (left) vs. before (right) undergoing a YAG posterior capsulotomy. All photos: Nate Lighthizer, OD. |

Regardless of your specific state’s requirements, Chris Wroten, OD, of the Bond-Wroten Eye Clinics in southeast Louisiana, highly recommends participating in continuing education courses that review laser protocols and procedures as you begin adopting these services. Check with your state’s optometric association to see if there are any trainings being offered.

In addition, take advantage of the expertise of your optometric colleagues, adds James Hunter, OD, an adjunct clinical professor at the Indiana University School of Optometry. “If you have a question or are unsure how to proceed, ask a fellow optometrist who is already offering these services,” he recommends. “Learning from one another helps us grow as individual practitioners as well as a profession as a whole.”

“Staff training is also important to ensure confidence in assisting with each procedure,” notes Joe Sugg, OD, immediate past president of the Arkansas Optometric Association. “We keep a step-by-step guide available for the staff to reference and have found staff members are as excited as we are to offer this care to our patients.”

Stocking the Equipment

Aside from the laser itself, there are very few additional things you will need to purchase that aren’t already on hand in the office, according to Dr. Wroten. “Laser lenses are required to perform SLT and LPI, but are optional for YAG laser posterior capsulotomy,” he explains. “The use of laser lenses necessitates having conditioning fluid on hand (e.g., Goniosol, Goniovisc, Celluvisc), while topical ocular hypotensives (e.g., brimonidine) and topical anesthetics (e.g., tetracaine, proparacaine) are also needed.”

As for the lasers themselves, there are several different companies that offer equipment to lease or purchase. “Some lasers are stand-alone for each type of procedure and others are combination lasers,” says Dr. Sugg. “It is up to the individual doctor to decide which laser type best meets the needs of their patients and the clinic space they have available to house the laser.”

|

|

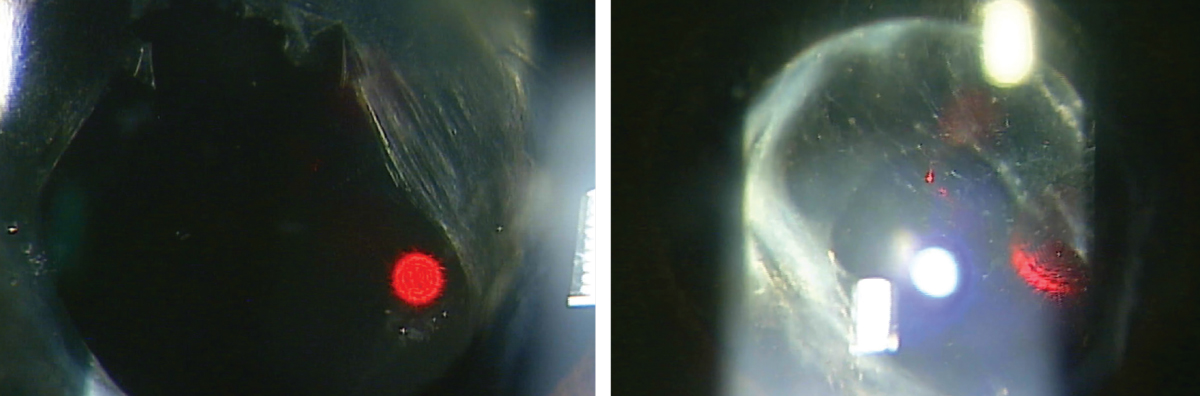

A laser peripheral iridotomy patient before (left) and after (right) the procedure. Click image to enlarge. |

While lasers involve a significant financial investment, there are some misconceptions regarding their overall cost, according to Dr. Wroten. “Most new YAG/SLT combo lasers cost less than $40,000,” he notes, “which is much less than a new OCT scanner. Additionally, new standalone YAG lasers can be purchased for under $20,000, with refurbished, warrantied units costing even less.”

You need not go it alone, he says. “Given their portability, multiple doctors/practices can purchase and share a laser, or laser rental services can be used where the laser is serviced, transported, set up and taken down by the rental company, and the doctor pays a per-patient usage fee,” he advises. “Keep in mind that while reimbursements vary by procedure type, carrier and geographic location, they are also significantly higher than for OCT procedures by comparison.”

For ODs who are hesitant to offer these new procedures due to cost, Dr. Lighthizer urges them to consider the professional value and satisfaction of adding a new service like lasers. “It is very rewarding—finances aside—to do something in the office that provides a great benefit for our patients,” he notes. “The more care you can provide for your patients—whether it’s a drop, oral medication or procedure—the more fulfillment you will have as a doctor, and the happier your patients will be.”

Virginia: A Recent Success StoryThanks to a bill that passed in March of this year, optometrists in Virginia will now have the ability to perform three types of laser surgery— YAG capsulotomy, LPI and SLT. This scope of practice expansion is beneficial for both ODs and their patients, notes Lisa Gontarek, OD, president of the Virginia Optometric Association (VOA). Not only does this ensure timely care, but it also allows patients to remain in the care of a provider they know and trust. “Because optometrists outnumber ophthalmologists 2.5 to 1 in Virginia, ODs are typically closer to patient’s homes and can get the patient in for treatment sooner,” says Dr. Gontarek. “This is especially beneficial in rural areas. As the largest state that permits optometrists to use lasers, we hope that our success in Virginia will help to pave the way for other states to expand their scope of practice as well.” The bill will finally go into effect on July 1st after four years of planning and advocacy for scope expansion by the VOA. From the very beginning, they encouraged active members to complete an advanced procedure and laser certification course, explains Dr. Gontarek, who noted that by the time the bills were taken to the General Assembly, close to 150 doctors were already certified. The Virginia Board of Optometry is now working on setting a regulatory process, and once that is completed, the VOA will be able to help its members navigate the process of certification and implementation. When asked what contributed to the success of Virginia’s legislative efforts, Dr. Gontarek emphasized the importance of an organized and well-executed plan that included a strong grassroots network, outstanding legislative committee leadership and a hardworking executive director and lobbyists, in addition to the full and loyal support of VOA members. “It was a team effort from start to finish. I highly recommend that any state working toward scope expansion be fully prepared before pressing forward,” she says. “The process is a huge investment of time and money. It is just too important to take on halfheartedly.” |

Another consideration for ODs is coding and billing. While this is fairly straightforward for laser procedures, Dr. Wroten explains that it may require amending some claims initially based on individual carrier requirements and/or insuring carrier protocols. For example, some insurers require a visual field and gonioscopy within the 12 months prior to SLT being performed.

Practical Advice for ODs

Before embarking on the task of incorporating lasers into your practice, again, it is important to consult your state board to determine the specific procedures that are permitted under your state’s scope expansion legislation.

Successful laser procedures begin with the basics, including something optometrists have been doing for years, according to Dr. Hunter, which is diagnosis. “For instance, the appropriate use of lasers in glaucoma is centered around the appropriate diagnosis of the type of glaucoma,” he says. “Then, the application of the laser treatment becomes the use of a slit lamp, which optometrists have used for decades, followed by applying the scientific-based settings for the laser for each individual condition.”

As with any intervention, a thorough medical history is required. “With rare exceptions, laser procedures are contraindicated if active intraocular inflammation is present, retinal issues exist (e.g., macular edema, macular hole, epiretinal membrane), patients are unable to fixate or if corneal opacities prevent adequate visualization of the surgical site,” notes Dr. Wroten.

Optimizing Laser Procedures: Advice From a ProLooking for clinical tips and advice as you incorporate lasers into your practice? Dr. Wroten offers step-by-step recommendations to optimize three common ocular laser procedures below. YAG laser posterior capsulotomy. The common initial laser settings for this procedure are single pulse, ~250μm posterior offset, starting energy of 1.2-1.8 mJ (higher for capsular fibrosis/denser opacification), moderate magnification and relatively high illumination for both the slit lamp light and for the focusing beam. The most common YAG posterior capsulotomy treatment pattern is the cruciate/cross-shaped pattern; alternatively, the hinged, circular, spiral or star patterns may be used, all with the goal of creating a visible opening in the posterior capsule that is slightly larger than the scotopic pupil size (thus the surgery is performed with the pupil dilated). Intraoperatively, should the doctor have difficulty determining the focal plane due to reflections, one technique to assist is to focus the HeNe beam on the iris, then move over to the pupil without changing the plane of focus, and finally move the beam toward the patient to focus on the posterior capsule. To decrease the chance of pitting the IOL, since there is a shockwave of energy that travels back toward the doctor from the laser’s focal plane, a posterior offset is often used. Additionally, the OD can intentionally defocus the HeNe beams behind the capsule initially, then pull the HeNe beam anteriorly to focus on the capsule before firing. If total energy used exceeds 100-150mJ in a single session, consider bringing the patient back on another day to finish. Whether or not to use a YAG laser capsulotomy lens is solely at the discretion of the doctor. Using a lens may increase accuracy, reduce the number of shots and totally energy required and provide better control of the eye during the procedure. On the flip side, it also adds time, requires conditioning fluid and increases the number of reflections in the doctor’s view. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT). Common initial energy settings include power at 0.8-1.0 mJ; moderate magnification and high illumination settings for the slit lamp and focusing beam; the counter is set to zero and the spot size and other laser settings are fixed. An SLT laser lens is necessary to visualize the angle of the eye and treatments are generally applied 360 degrees to the trabecular meshwork using adjacent, non-overlapping spots (typically about 100 shots total). The goal during surgery is to see tiny “champagne bubbles” in the anterior chamber when the laser is fired. Keep in mind that SLT is contraindicated for neovascular glaucoma, and energy settings can be decreased for patients with heavily pigmented trabecular meshwork. Laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI). The common initial energy settings for this procedure are single, double or triple burst setting; energy = 2.5-3.0 mJ with no offset; and use of an iridotomy lens to focus laser energy, provide magnification and help identify an iris crypt (i.e., thin area of the iris) for creating the iridotomy. Keep in mind that an LPI can less commonly be performed using an argon laser, but settings will differ from the ones just outlined. Pilocarpine may be used preoperatively to tighten the iris, and the iridotomy is created about one-third of the way from the limbus toward the pupillary margin, located at either 11:00 or 9:00 OD, and at either 1:00 or 3:00 OS, with some studies suggesting the chances of postoperative dysphotopsia are lessened with the 9:00 OD and 3:00 OS locations. The endpoint is reached when a “plume” of aqueous is observed entering the anterior chamber after a laser shot, then the opening is enlarged to approximately 1mm in diameter. |

On the day of surgery, the laser should be properly focused by the doctor and the type of surgery, as well as the eye to be operated on, should be verified multiple times, according to Dr. Wroten. He also notes that appropriate informed consent should be obtained to include alternatives to the procedure and potential complications.

|

|

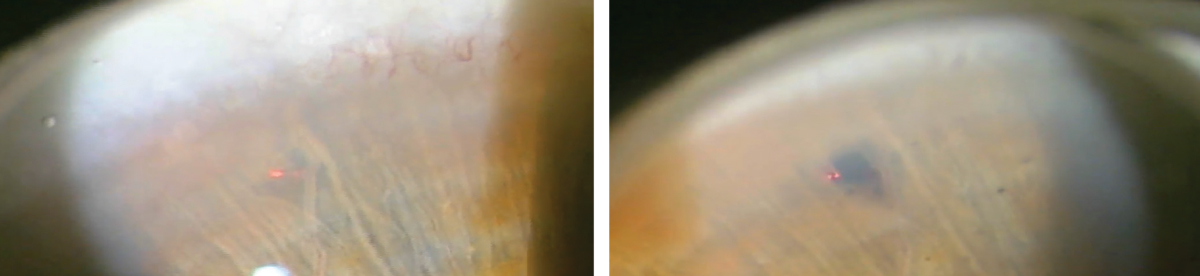

Another patient before (top) and after (bottom) YAG posterior capsulotomy. Click image to enlarge. |

“After the laser counter is zeroed out and the laser settings are adjusted appropriately, the patient should be educated on what to expect during the surgery,” he explains. “For instance, YAG posterior capsulotomy is typically painless, but the patient may hear a ‘snap’ when the laser fires. SLT may produce a mild stinging sensation during the procedure with slight soreness the following day, and YAG LPI may also be slightly uncomfortable for the patient.” Eliminating surprises during and after the procedure will help ease a patient’s anxiety and increase their trust in you as their doctor.

On the day of the procedure, intraocular pressure (IOP) should be measured prior to surgery for YAG posterior capsulotomy, SLT and LPI to ensure it’s safe to proceed, advises Dr. Wroten. A topical ocular hypotensive—most commonly brimonidine—is instilled in the eye at least 20 minutes prior to surgery and then shortly after the procedure is completed.

“IOP is reassessed 20 to 60 minutes postoperatively to monitor for spikes, which are then treated if indicated,” Dr. Wroten says. He also notes that verbal and written instructions should be provided to the patient and include any postoperative medications that need to be taken, as well as their appropriate dosage amounts. For example, in cases of YAG posterior capsulotomy and LPI, this is typically a topical steroid QID for one week. For SLT, either no drops, a topical NSAID or a topical steroid may be prescribed QID for five to seven days.

These instructions should also outline potential complications, such as pain, redness, blurred vision, photopsia, dysphotopsia and floaters, in addition to how, when and whom the patient should contact if complications arise and when to return for follow-up. See the sidebar on the previous page for other clinical pearls from Dr. Wroten.

When performing YAG laser capsulotomy, Dr. Sugg emphasizes the importance of staying on plane and continually advancing the opening. “It’s always tempting to chase the capsule posteriorly and to try and make it look perfect, but it’s just not going to look as clean and perfect as you want it to immediately,” he explains. “If you keep moving on plane and advancing the capsulotomy, those capsular flaps will open and move further posteriorly with time, and it will look more like you want it to by the one-week follow-up appointment. This allows you to put less overall energy in the eye.”

Also, he urges ODs not to be afraid to increase the energy setting because this can allow for a more efficient capsulotomy, and you might actually put less overall energy in the eye by increasing the amount of energy per pulse.

“Regarding SLT, your ability to perform this procedure is tied directly to your gonioscopy skills,” Dr. Sugg says. “If you are confident in these skills, or if you take the time to become confident in these skills, then there really isn’t much more to performing an SLT. Of course, you must be familiar with the proper settings and how to adjust them.”

Laser Laws and Access to CareA recent study suggests that adding optometric laser privileges in Oklahoma, Louisiana and Kentucky has not expanded access to such care for patients, according to findings presented during the 2022 ARVO annual meeting in Denver.1 The data showed that optometrists cover an area similar to that covered by ophthalmologists for SLT and YAG procedures, according to the study authors. They reported that for SLT the percent of the population covered within 30 minutes of driving time by optometrists and ophthalmologists was 73.4% and 84.1%, respectively. For YAG procedures, it was 84.8% for optometrists compared with 85.3% for ophthalmologists. The research also found that for both procedures, the percent of the population covered exclusively by optometrists was 5.6% compared with 6.1% by ophthalmologists. These findings, the study authors conclude, suggest that expansion of laser authority for optometrists has not resulted in a statistically significant increase in access to these procedures for patients. Commenting on these findings, well-known Kentucky optometrist Ben Gaddie emphasized that scope of practice legislation was never about replacing or overtaking the volume of laser being performed, but rather a way to augment the care delivered by their ophthalmological colleagues. “Access to care isn’t necessarily a volume game; keep in mind that there is a reason why these smaller population areas don’t have as much access,” says Dr. Gaddie. “In these settings, optometric laser care has been an essential benefit, and I can personally attest to this,” he notes. “Even in more metropolitan areas, patients don’t like to go through the hassle and expense of being treated in the physician-owned surgery center. They pay a facility charge and physician charge, as well as having to wait in an ASC setting. Patients appreciate having their own doctor perform the procedure right in the office.” Over the last decade, Dr. Gaddie has witnessed firsthand the impact of expanded scope of practice in Kentucky. “We have an office in a county of 10,500 people where we are the only eye care providers in the county (we have an ophthalmologist that comes in and does cataract surgery twice a month) and the only providers in a contiguous six counties thereafter,” he notes. “The socioeconomic reality in many of our rural communities is that $5.00/gallon gas prices and a two-hour plus round-trip drive for a laser isn’t feasible. We are providing an alternative for those who don’t want to or can’t drive to Louisville or Lexington.” 1. Shaffer J. Evaluating access to laser therapy by driving distance using Medicare data and geographic information systems mapping. ARVO 2022 Denver. |

Advocating for Change

While scope expansion progress continues at a healthy pace, many states still do not recognize the full extent of education and training ODs possess to successfully perform laser procedures. Therefore, it is important that optometrists continue to advocate for themselves and their profession.

|

|

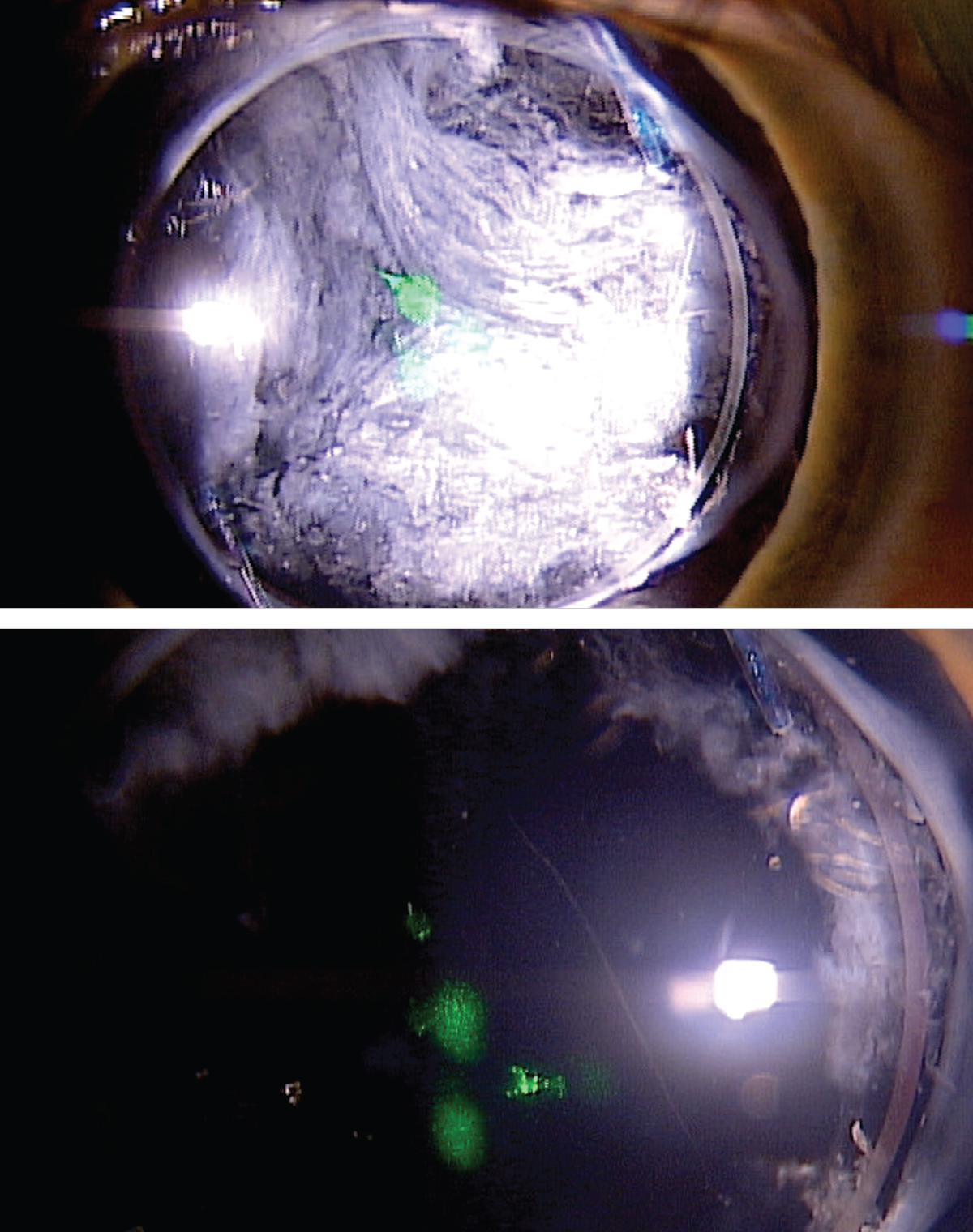

SLT during the procedure. Notice the difference between tissue about to be treated (up and to the right of the red beam) compared to the tissue already treated (down and to the left of the red beam). Click image to enlarge. |

Lisa V. Gontarek, OD, who serves as president of the Virginia Optometric Association, urges optometrists to get involved at the local, state and national levels. “Organized optometry is the only way we move our great profession forward,” she says, while noting that involvement looks different for everyone. “Some are able to do more than others, and that’s okay. Do what you can. We will always be stronger together.”

Actively advocating for optometric practice begins by joining your state association, notes Dr. Hunter, while also emphasizing the important role ODs play in the profession’s growth. Other ways to get involved include donating to state and AOA PAC, building relationships with legislators, participating in Legislative day or volunteering in your local optometry society.

“To keep optometry pertinent and at the forefront of the healthcare arena, it is incumbent upon us to keep moving our profession forward. In order to do that, we must educate the public and our patients about what we do,” says Dr. Gontarek. “While not all optometrists will necessarily incorporate every scope expansion into their practices, we should all support those who want to. Otherwise, our profession will become stagnant, and our patients will suffer for it.”

Continued Expansion

As the role of optometrists continues to grow with the ongoing scope of practice expansion, it is important that ODs take advantage of these practice authority wins. Dr. Lighthizer recognizes that incorporating laser procedures can be daunting, but he reminds optometrists that they have the knowledge and skills to be successful.

“Remember, this is within your education and training,” he says. “But, just because you have a laser and a patient doesn’t mean you have to perform that procedure. Take your time when you first start offering these services. Choose your patients wisely. It’s okay to start with straightforward cases and refer more complicated ones out until you build your confidence. And if you have no interest in providing these procedures, refer to your optometric colleagues who do.”

When ODs practice to the full extent of their clinical abilities, everyone benefits, notes Dr. Hunter. “As the general population continues to age, there is going to be an increasing need for eye care services, including laser treatments. Coupled with a decreasing number of ophthalmic surgeons, optometrists will need to expand within their scope of practice to meet this demand,” he says. “ODs are perfectly positioned to provide this care, and doing so offers significant value to our patients.”

Next month: Part 3 of this series will delve into glaucoma medication prescribing privileges and optometric glaucoma comanagement more broadly.