|

A 55-year old Hispanic male presented for an evaluation of blurred vision in his right eye. He explained that approximately one year ago, he noted distortion in the right eye and color vision changes. An ophthalmologist noted fluid leaking in the back of his eye. The distortion resolved and his vision improved in a few months.

Then, three months ago he reported another episode of blurred vision and distortion, mostly while driving. He felt the vision had improved, but it still was not “right.” He has never had any eye problems and his medical history was unremarkable.

Upon examination, his entering visual acuity measured 20/30 OD and 20/20 OS. With a manifest refraction of +2.50D he was 20/20 OU. The left eye had a minimal hyperopic correction. Confrontation fields were full to careful finger counting in both eyes. Extraocular motility testing was unremarkable. His pupils were equally round and reactive; there was no afferent pupillary defect.

Anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Dilated fundus examination showed small cups with good rim coloration and perfusion in both of his eyes.

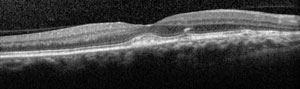

The posterior pole of the right eye showed changes (Figure 1). Fundus images of the left eye are also available (Figure 2).

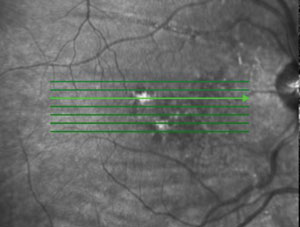

An SD-OCT is also available for review (Figures 3a and 3b).

| |

| Figs. 1 & 2. Fundus images of the right (above) and left (below) eyes of our patient. Note the unusual changes in the right eye. |

Take the Quiz

1. What are the changes seen in the posterior pole of the right eye?

a. Subretinal fluid.

b. Choroidal folds.

c. Retinal stria.

d. SubRPE tracking from a parasite.

2. What is the etiology?

a. Inflammation.

b. Hypotony.

c. Orbital tumor.

d. Idiopathic.

3. What is the likely explanation for the fluid in the back of his eye?

a. Impossible to tell.

b. Cystoid macular edema.

c. Choroidal neovascular membrane.

d. Idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy (ICSC).

4. What additional test would be helpful to confirm the diagnosis?

a. Fluorescein angiography.

b. MRI.

c. Orbital ultrasound.

d. Visual field.

5. How should this patient be managed?

a. Observation.

b. Intravitreal anti-VEGF medication.

c. Refer to neuro-ophthalmologist.

d. Start anti-helminthic medications.

For answers, see below.

Discussion

Our patient has choroidal folds in the right eye. On clinical exam, we can see, throughout the entirety of the posterior pole, horizontal linear lines that alternate in color between light and dark. These are folds, or wrinkles, in the inner portion of the choroid, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and neurosensory retina. They develop as a result of shrinkage of the sclera or from scleral thickening.1 This may occur in a number of conditions including orbital inflammatory disease (posterior scleritis or inflammatory pseudotumor), hypotony following intraocular surgery, choroidal neovascularization and orbital tumors, among others. Any of these conditions can result in shrinkage of the sclera which, in turn, causes a reduction in the area of the inner surface of the sclera.1 When this occurs, the choroid and RPE become redundant relative to the area of the sclera and choroidal folds develop.

In the majority of cases, choroidal folds will result from idiopathic causes. They are usually an incidental finding in patients during a routine eye examination.1 They may involve most of the posterior pole of the eye, or can be confined to an area either above or below the macula and optic disc. Their distribution in both eyes is usually symmetric. In most instances visual acuity is unaffected.1

| |

| Figs. 3a and 3b. Do these SD-OCT images point to the patient’s pathology? |

Choroidal folds can also be seen in moderate or high hyperopia due to these patients’ shorter axial length and thick scleras.1 This can occur at any age, but is most commonly seen in middle-aged adults. They can be unilateral, but are more often bilateral.1

It has been ingrained in most clinicians that unilateral choroidal folds may be the result of an orbital tumor pressing on the back of the globe. However, it is important to note that orbital tumors will not cause choroidal folds, unless scleral thickening or shrinkage occurs.1

The diagnosis of choroidal folds is generally based on the clinical appearance; however, fluorescein angiography may highlight the folds better than what is seen on clinical exam. In our patient, the folds were quite obvious, so we did not feel we needed a fluorescein angiography to confirm the diagnosis. If there was concern of an orbital mass or inflammatory process, an orbital ultrasound would have been helpful. We did not feel there was any resistance to retropulsion so we did not perform an ultrasound. We did perform an OCT, as there was RPE modeling in the macula. The OCT show some irregularity at the level of the RPE but there was no CNV (Figures 3a and 3b).

So why does our patient have choroidal folds? Based on the history our patient provided, we thought he might have had an episode of central serous chorioretinopathy.

The previous doctor told the patient there was fluid in the back of his eye. This may have been a neurosensory detachment. As most cases of ICSC will resolve on its own without treatment, that may very well be what happened.1 The RPE mottling in the macula is consistent with resolved ICSC, and old ICSC has been known to result in choroidal folds.1

We discussed these findings with our patient and explained to him that, should he notice any other changes in his vision, he should return to the office immediately for further evaluation.

1. Gass JD. Choioretinal folds. In: Gass JD, editor. Stereoscopic atlas of macular disease: Diagnosis and treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. pp. 288–301.

Retina Quiz Answers:1) b; 2) d; 3) d; 4) a; 5) a.