|

Nearly 30 years ago, a staff member knocked on my exam door and said I had a call from a referring physician. I normally don’t let anything interrupt my appointments, but my coworker was very insistent. I relented and excused myself to take the call in my office. I picked up the phone and said my usual, “Dr. Harris speaking, what can I do for you?” And the voice on the other end hit me with, “Doctor, what did you do to my patient?”

I was too caught off guard to know how to respond, and the silence that followed was deafening. Thankfully, the referring physician saved me from that awful moment and followed up with, “I think I might be able to reduce my patient’s medication for his Parkinson’s, and I need to understand what you did to him.” I took a deep breath and, knowing exactly what she was talking about now, knew things were going to be just fine. So, what did I do for this patient? Let me tell you the story about how prism caused a domino effect in his life.

|

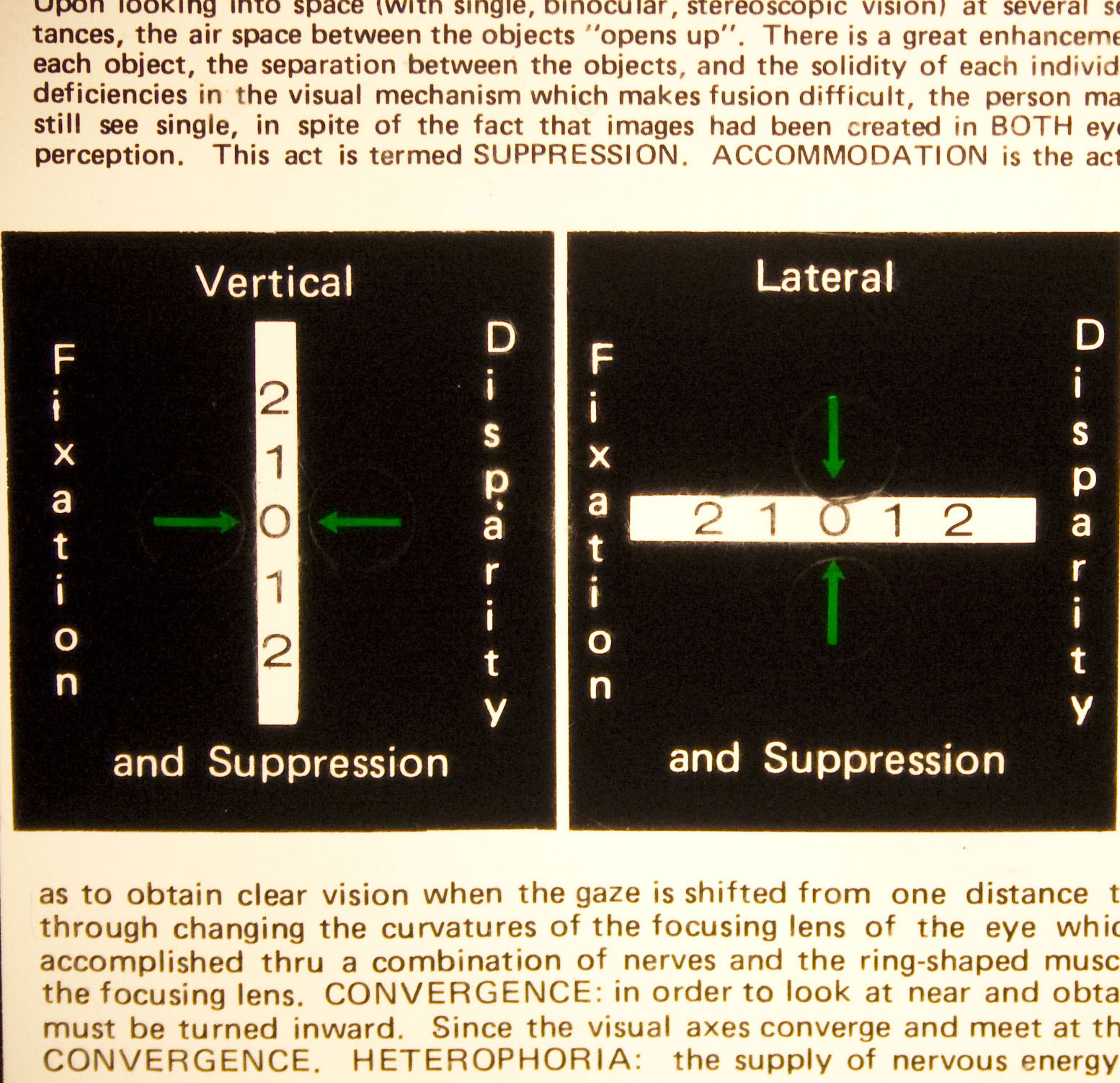

| This is the central part of a Mallett card. Each of the green arrows has a circular-shaped Polaroid material over it. When viewed with Polaroid glasses, the arrow to the right on the vertical test and the upper arrow on the lateral test can be seen with the right eye, and the other two can be seen with the left. Everything else is seen with both eyes and acts as fusion locks. Click image to enlarge. |

The Case

A previous vision therapy patient of mine had come in for her yearly exam and questioned me about her father. She explained that he was experiencing some odd symptoms that she didn’t understand and that he was being treated for Parkinson’s disease. She asked if I would examine him, and I immediately agreed.

The exam proceeded naturally through the history and data collection, with no glaringly abnormal findings. I noticed on the cover test that there appeared to be a slight vertical deviation along with an exophoria. The exophoria was larger at near, and the vertical deviation seemed to occur at both distance and near.

As part of the analytical exam, I usually perform phorias at distance and near and horizontal base-in and base-out at distance and near. The phorias matched the cover test with 5∅ of exo at distance and 14∅ of exo at near. The base-in and base-out ranges had strayed from normal, showing very reduced break points. The base-out break at distance was 5∅ instead of 19∅, and the base-in break at distance was 3∅ instead of 9∅. At near, with the fused cross-cylinder of +2.50 add in place, the reductions were similar.

I conducted vertical phoria testing and found 4∅ of left hyper at both distance and near. I redid the horizontal prism testing with the vertical compensating prism in place. I put 4∅ in front of the left eye and used the Risley prism on the right eye to find the ranges. I knew that the patient might perceive the target moving right and left as I put in asymmetric lateral prism, and that’s exactly what happened. However, his break points nearly tripled in both directions. These improvements confirmed I should indeed prescribe the prism.

|

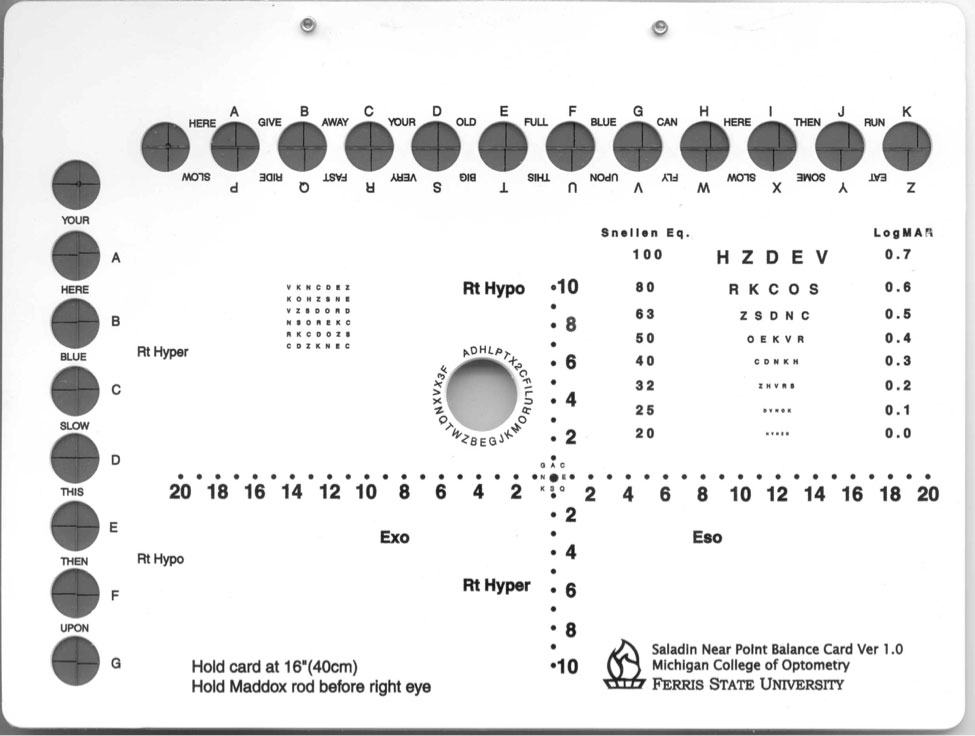

| The Saladin card has targets for measuring fixation disparities in both the horizontal and vertical directions. Click image to enlarge. |

Perks of Prism

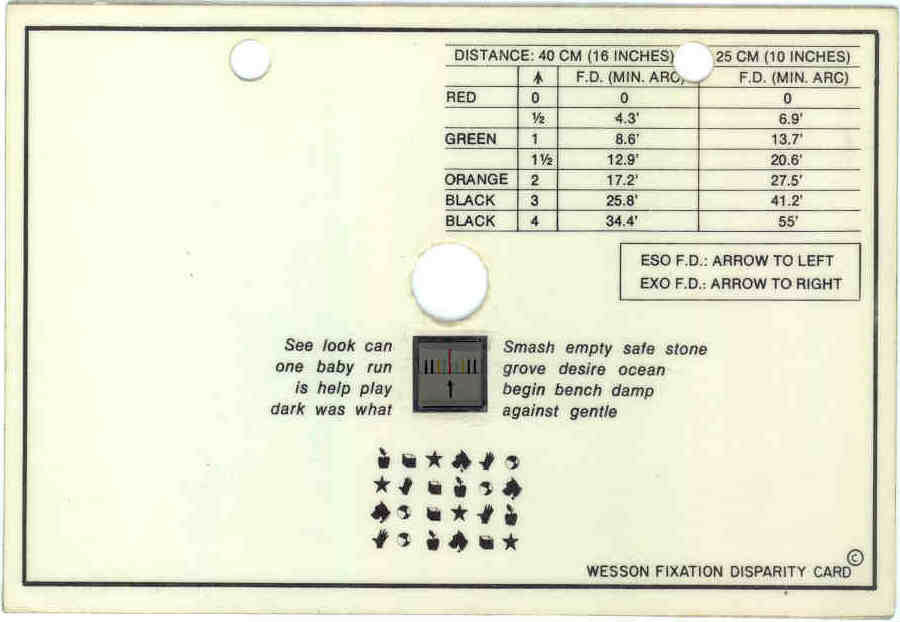

Even though I had determined the amount of prism based on von Graefe testing, I usually try to find a way to prescribe less if possible. I plotted the patient’s fixation disparity curve for the vertical misalignment and found that with the 4∅ of vertical in place, there was no residual fixation disparity. Though the arrows were not perfectly aligned on the Mallett card with 3∅, the misalignment was minimal. With 2∅, the slippage was too much.1

I trial-framed the 3∅ of vertical while the patient was in the chair. He reported less trouble with his vision and felt more relaxed. He did not complain of double vision. However, I found a small vertical misalignment. I decided to try some vertical prism. With it, the patient felt even more relaxed. It also greatly increased his range of clear binocular vision.

When the patient received his new pair of glasses, he again expressed how much better they made him feel. A couple of days later, he had the appointment with his primary care physician that prompted the call to my office. His doctor found that he was far more stable with Romberg testing than he had been in years. According to her assessment, his tremors had subsided as well. She felt that if his improvement persisted or improved further through his next follow-up visit, she might be able to reduce his Parkinson’s medication.

Over time, the patient did remain stable, and his medication was reduced accordingly. He was my patient for over 15 years and continued to love his glasses with the small amount of prism.

|

| At near, fixation disparity and the associated phoria can be found with a Wesson card. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Small vertical misalignments may be present more often than we know. Generally, it is hard to detect misalignments of 4∅ or less on a cover test, even for most well-trained optometrists.

My gut feeling that there was something off about this patient’s cover test results—a slight head tilt if nothing else—along with his very small base-in and base-out ranges, prompted me to perform vertical phoria testing, vertical ranges and vertical fixation disparity testing.

The patient’s daughter, my original patient, thought I might recommend vision therapy for her father, but the lenses took care of his symptoms all on their own, even though they didn’t actually treat his underlying condition. The prism helped meet my patient’s needs more than I could have ever imagined, and his primary care physician made sure I knew it.

This case brought home a theme that is often quite easy to lose sight of: everything is connected. We saw how correcting a small vertical misalignment profoundly changed the life of a patient, so much so that his physician felt she could reduce his medication for his Parkinson’s’ disease.

We truly practice a wonderful profession and have the power to change people’s lives in more ways than one with our simple tools.

Dr. Taub is a professor, chief of the Vision Therapy and Rehabilitation service and co-supervisor of the Vision Therapy and Pediatrics residency at Southern College of Optometry (SCO) in Memphis. He specializes in vision therapy, pediatrics and brain injury. Dr. Harris is also a professor at SCO. Previously, he was in private practice in Baltimore for 30 years. His interests are in behavioral vision care, vision therapy, pediatrics, brain injury and electrodiagnostics. They have no financial interests to disclose.

| 1. Suter PS, Harvey LH. Vision Rehabilitation: Multidisciplinary Care of the Patient Following Brain Injury. Routledge; 2011. |