In April 2016, optometry lost a giant when the author of the seminal work Primary Care of the Posterior Segment, Larry Alexander, OD, died. In addition to being an optometric physician, author and educator at the University of Alabama Birmingham School of Optometry, Dr. Alexander was a past president of the Optometric Retina Society (ORS). That group chose to honor his legacy by accepting case reports from optometric residents across the country relating to vitreoretinal disease.

This case, selected by the ORS Awards Committee, was co-winner of the sixth annual Larry Alexander Resident Case Report Contest. The contest is sponsored by Topcon, Visionix (Optovue) and Heidelberg.

Bartonella bacteria is transmitted to humans via scratches, bites or licks from flea-infested cats. Bartonella henselae infection is responsible for roughly 22,000 cases of cat scratch disease per year in the United States. Its prevalence is higher in children and young adults, aged 21 to 35, and those who have daily close contact with cats, such as veterinarians.1,2 Patients commonly have systemic symptoms including a vesicle/papule forming at the site of inoculation, lymphadenopathy, fever and malaise. Ocular involvement occurs in 5% to 10% of patients, with blurry vision being the most common symptom. Ocular signs can vary from mild anterior chamber reaction and vitritis to severe optic nerve head edema, macular star, exudative retinal detachment and retinochoroiditis. Diagnosis for Bartonella henselae is made via blood testing for Bartonella antibodies.

This case report will discuss a young patient with severe bilateral neuroretinitis serologically confirmed to be caused by Bartonella henselae and will walk you through ways to detect the condition, potential differentials to consider and which treatment and management options are available.

Case Presentation

| Check out the other winning submission of the ORS resident case report contest on multifocal vitelliform dystrophy. |

An 18-year-old female presented to the urgent care clinic complaining of a dark spot with a shadow in the superior temporal portion of her right eye as well as a circular shimmering in her left eye that began five days ago and was worsening. She also reported mild blurry vision, discomfort and a sense of heaviness in her right eye. The patient denied any ocular pain or flashes of light. Systemically, the patient reported transient headaches with tinnitus in both ears, and she was sick for four days with a 103-degree fever approximately eight days prior to presenting to the urgent care clinic. Upon further questioning, the patient did report that she had cats that were currently being treated for fleas. Her medical records were positive for generalized anxiety controlled with Zoloft, Sprintec for birth control and ketoconazole for eczema in the ears.

|

|

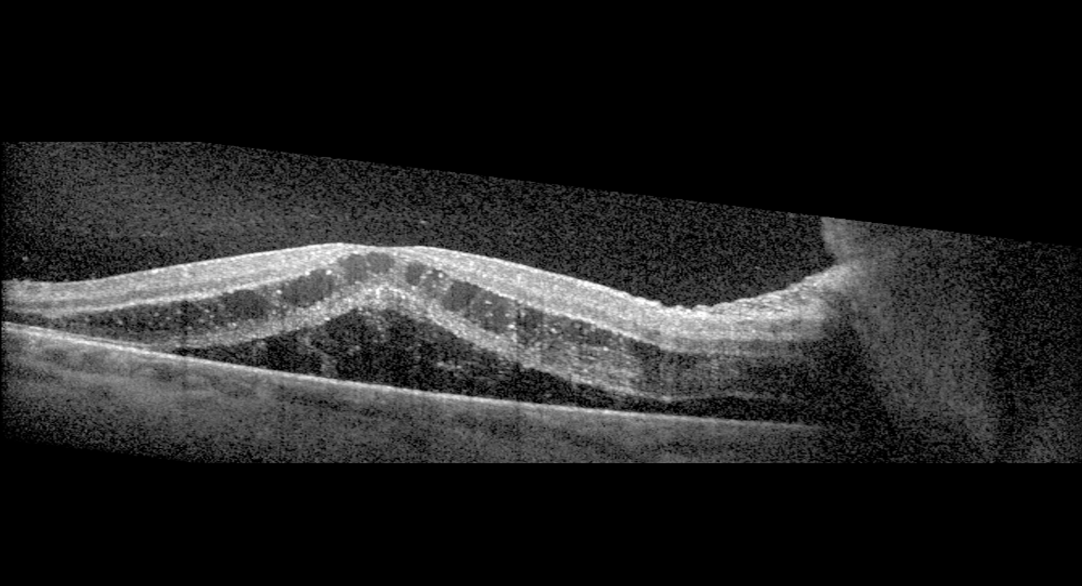

Figure 1. Right eye with 4+ optic nerve head edema with overlying granuloma, cystoid macular edema, and myelinated retinal nerve fiber layer with possible retinitis. Click image to enlarge. |

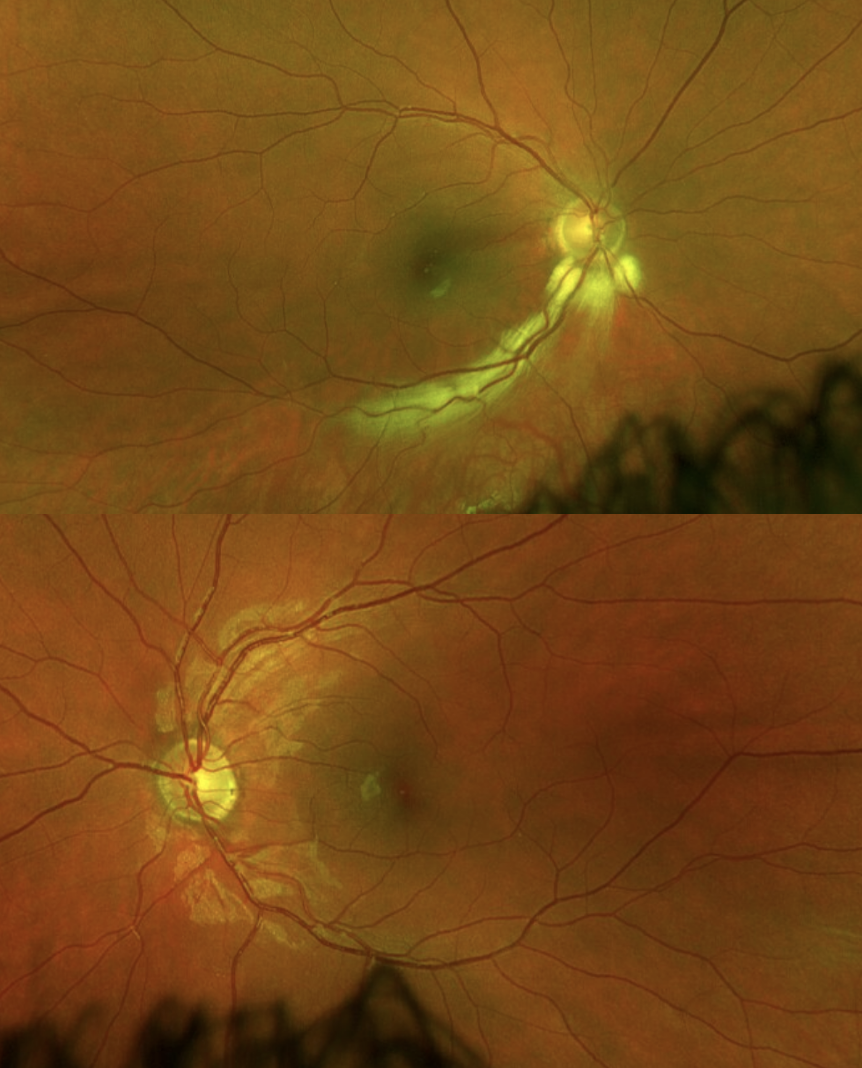

The patient’s last eye exam was 12 years prior, and aside from having ‘extra tissue’ in the back of one of her eyes, the exam was overall unremarkable. She denied ocular problems prior to the urgent care visit. Upon clinical examination, the patient’s visual acuities were 20/250 OD, with no improvement with pinhole, and 20/20 OS. Extraocular motilities and confrontation visual field were both normal. Intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 10 mmHg OD and 11 mmHg OS. Anterior segment was remarkable for trace to 1+ cell and trace flare in the anterior chamber of the right eye and trace cell in the left eye, likely due to a spillover from the posterior inflammation. Posteriorly, for the right eye, the patient had 4+ optic nerve head edema with an overlying granuloma, myelinated retinal nerve fiber layer extending inferior temporal from the optic nerve head, macular edema and scattered snowballs in the periphery with 1+ vitreous cells (Figure 1). In the left eye, there was 2-3+ optic nerve head edema with disc hemorrhages and trace vitreous cells. No macular edema was noted (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2. Left eye with 2-3+ optic nerve head edema with disc hemorrhages and no cystoid macular edema. Click image to enlarge. |

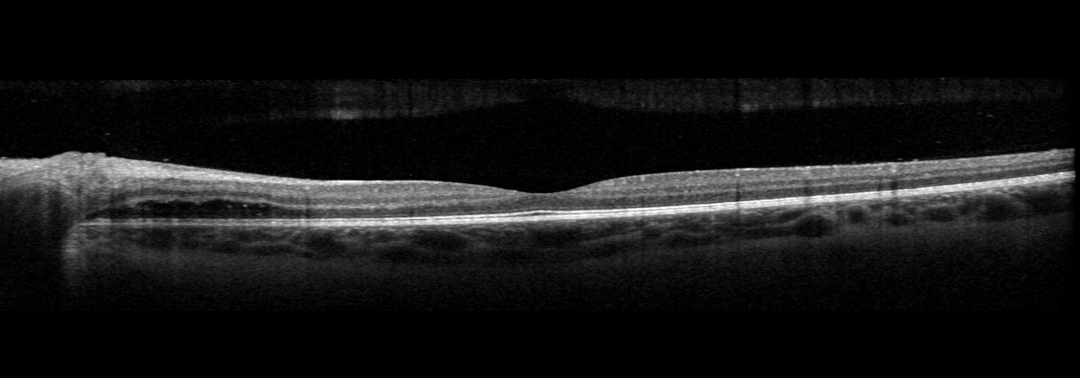

The first scan to be performed was OCT due to the significant amount of macular and optic nerve head edema. The macular OCT for the right eye confirmed the presence of cystoid macular edema with a serous macular detachment (Figure 3). In the left eye, there was subretinal fluid arising from the optic nerve head, but no cystoid macular edema or serous macular detachment was noted (Figure 4). Due to the optic nerve head and macular edema, this patient was diagnosed with bilateral neuroretinitis. Because of the patient's history of having flea-infested cats, Bartonella henselae was high on the differentials list. We also considered HIV/AIDs, HZV/HSV, leptospirosis, Lyme, syphilis, toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis and typhus, as all of these conditions have been shown to cause neuroretinitis. Blood work was ordered, and serological testing showed positive Bartonella henselae IgG of >1:1024 (normal <1:64) and IgM 1:256 (normal <1:64). Typhus Fever IgG was also borderline positive with titers of 1:64 (normal <1:64), but this was likely a false positive. All other blood work was negative.

Due to the bilaterality and severity of the condition, the patient was referred to a retinal specialist. The retinal specialist concurred with the bilateral neuroretinitis diagnosis with high suspicion for Bartonella henselae. Additional blood work was done to rule out sarcoidosis as a cause. The patient was started on doxycycline 100mg po BID for three months and rifampin 300 mg po BID for six weeks. Retinal specialists continued to follow the patient for three months until her condition significantly improved.

|

|

Figure 3. OCT of the right eye: significant cystoid macular edema and serous macular detachment. Click image to enlarge. |

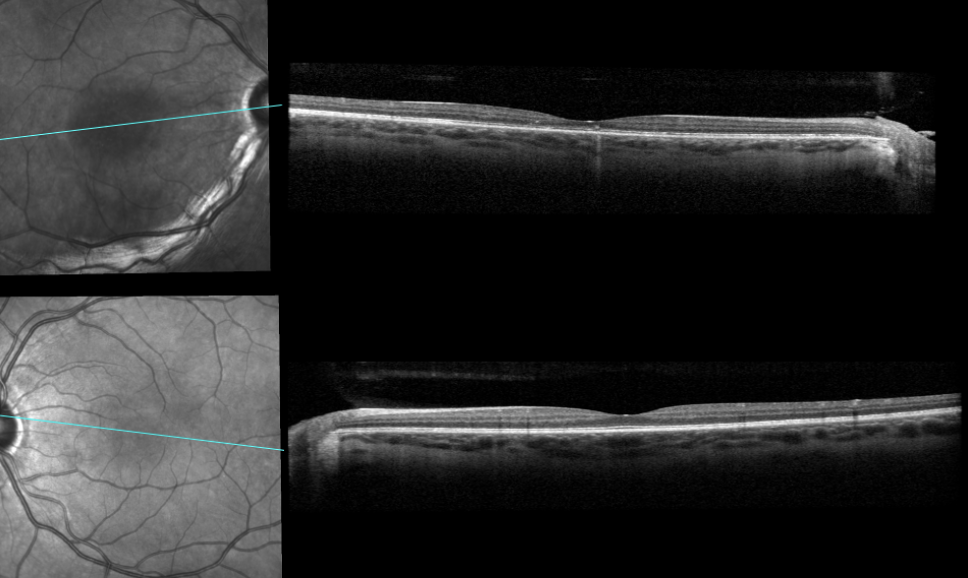

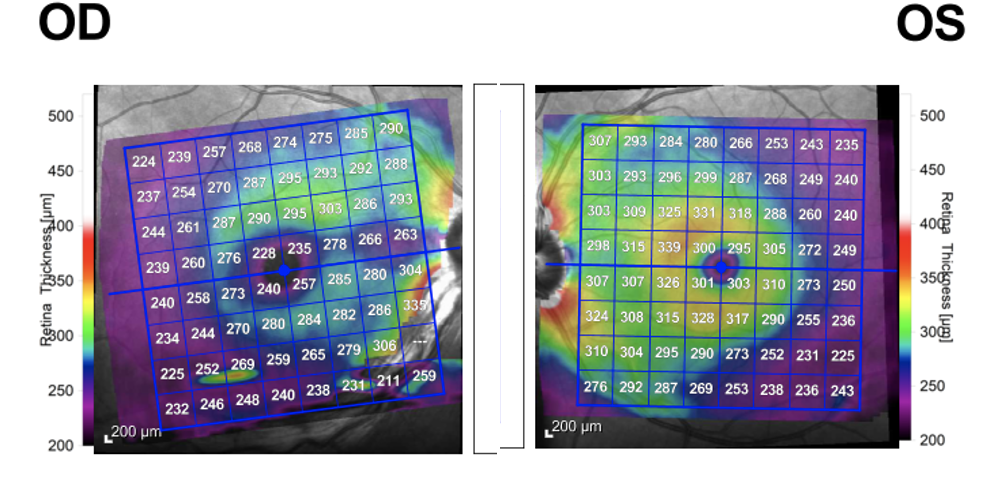

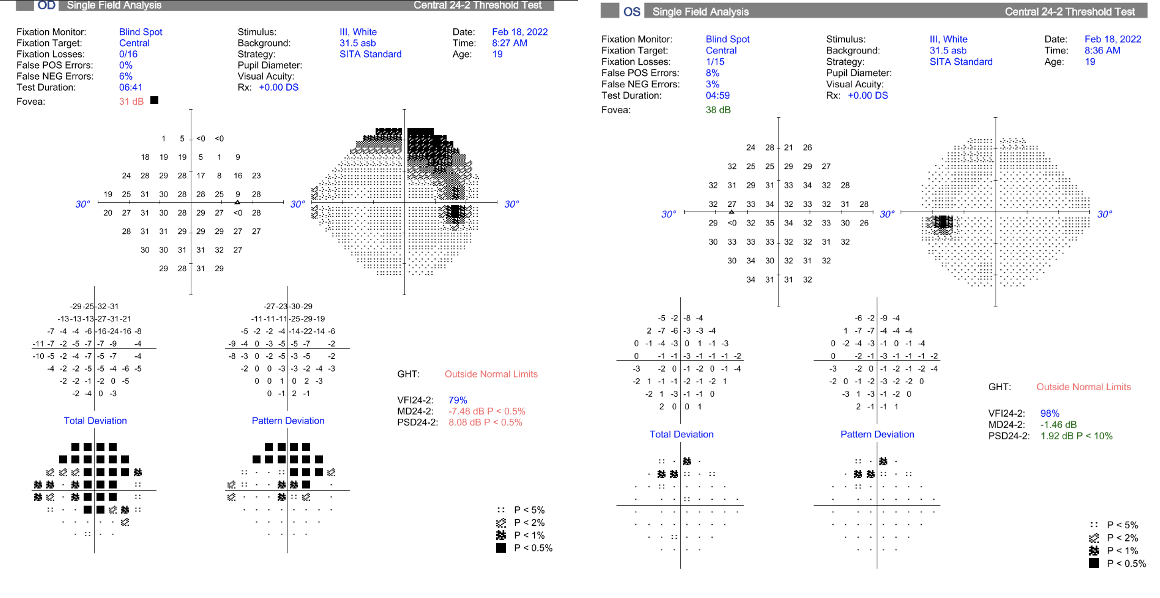

Four months after onset of symptoms, the patient returned to our due to having an increase in flashes of light. Visual acuities were 20/50 OD (20/40 with pinhole) and 20/20 OS. The patient still had a mild anterior vitritis of the right eye with trace to 1+ vitreous cells, but no optic nerve head or macular edema was noted, which was confirmed with OCT (Figures 5 and 6). The OCT did show that the right eye, which had sustained more severe inflammation, showed overall thinning of the retinal thickness, with the inferior retina being slightly worse than the superior retina (Figure 7). A 24-2 visual field test showed a superior arcuate defect that correlates with the area of myelinated nerve fiber layer and was possibly exacerbated by retinal thinning as a sequalae of inflammation (Figure 8).

The patient was started on topical prednisolone acetate 1% in the right eye six times per day for two weeks. At the patient’s follow-up two weeks later, her IOP was 29 mmHg OD and 15 mmHg OS. Brimonidine BID OD was

|

|

Figure 4. OCT of the left eye: note the absence of cystoid macular edema and mild subretinal fluid accumulating underneath the retina arising from the optic nerve head. Click image to enlarge. |

prescribed to lower IOP. One week later, the patient’s IOP remained elevated at 36 mmHg OD and 18 mmHg OS, with little to no improvement in the vitritis. The patient was switched to brimonidine-timolol BID, and the prednisolone acetate was tapered to QID. Since we suspected that the vitritis was likely a smoldering of the Bartonella henselae infection, the patient was prescribed a 30-day course of doxycycline 100 mg BID. At the next follow-up one week later, the patient had near complete resolution of the vitritis with only one cell noted, and her IOP improved to 21 mmHg OD and 18 mmHg OS. Because the patient reported poor compliance with the prednisolone acetate, the medication was discontinued. Brimonidine-timolol was continued BID for one more week.

Discussion

|

|

Figure 5. Four-month follow-up: resolution of optic nerve head and macular edema of both the right eye and left eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Bartonella henselae bacterial infection typically causes systemic symptoms to arise within two to three weeks after initial exposure, which may include lymphadenopathy, fever, chills and malaise. A vesicle/papule will likely also form at the site of inoculation. If it does occur, ocular involvement will present another two to three weeks after systemic symptoms, which is what the patient in this case experienced (her systemic symptoms began eight days prior to onset of ocular symptoms). Blurry vision is the most reported ocular symptom.1-4 Ocular signs include relative afferent pupillary defect, centrocecal visual field defects and color vision changes, in addition to mild anterior chamber reaction and vitritis. Additionally, in moderate to severe cases, ocular signs may include optic nerve head edema with telangiectatic vessels, exudative retinal detachment, retinal infiltrates, retinochoroiditis and a macular star that develops one to six weeks after the onset of optic nerve head edema.1,4,5 It is possible to have residual visual defects due to the significant amount of inflammation causing a branch retinal artery occlusion, although it is not common.5

However, with the patient in this case, since her visual field defect correlated with the area of myelinated nerve fiber layer, and since myelinated nerve fiber is a known cause of visual field defects, it is difficult to determine if her field defect is a result of the retinitis, the myelinated nerve fiber layer or a combination of the two.4,6 Because Bartonella henselae is not due to direct inoculation of the eye, it is thought that ocular signs and symptoms occur due to an immune response to Bartonella or due to parainfectious mechanisms.1 Bartonella henselae neuroretinitis is typically a unilateral condition with only 2% of patients demonstrating a bilateral neuroretinitis which is even rarer in children.2,7 Due to the bilaterality of the optic nerve edema, it can be difficult to differentiate between a bilateral case of neuroretinitis or a co-condition of increased intracranial pressure due to another disease process such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH).4 IIH was considered as another differential for this patient, as she was in the age and weight demographic, but this differential was low on the list. An MRI was ordered for the patient; however, the patient did not wish to have the MRI completed.

|

|

Figure 6. Four-month follow-up: The macular OCT of the right eye (top) shows resolution in macular edema and serous macular detachment. The macular OCT of the left eye (bottom) shows resolution of the subretinal fluid accumulation. Directly comparing the right to the left eye, you can observe retinal thinning of the right eye (also see Figure 7) with a flatter foveal contour leading to decreased visual acuity in the patient. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis for Bartonella henselae is typically made based on clinical findings of young age, history of close contact with cats being treated for fleas and having systemic symptoms prior to the onset of ocular symptoms. Diagnosis is confirmed by blood testing for Bartonella antibodies. Additional differentials should include other infectious diseases that cause neuroretinitis including HIV, HZV/HSV, leptospirosis, Lyme, syphilis, toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis and tuberculosis, all of which were tested, in addition to Dengue virus and chikungunya virus in endemic areas. Autoimmune conditions such as Sarcoidosis and Bechet’s disease should be considered as well.1,4

Treatment and Management

In mild cases, the disease is self-limiting. In moderate to severe cases, there are no standardized treatment guidelines due to a lack of completed clinical trials.3 However, most case reports and studies report positive outcomes from treatment with doxycycline 100 mg BID for two to six weeks in addition to rifampin 300 mg BID for two to four weeks in more severe cases. The treatment period may need to be longer depending on the severity of the case or if the patient is immunocompromised.1,3 Rifampin is typically added in severe cases because it is better able to penetrate the central nervous system.4 Other antibiotics such as azithromycin, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and gentamicin may also be considered instead of doxycycline, especially in young children for whom tetracyclines are contraindicated. The use of oral corticosteroids is considered to be controversial, but one study showed improved visual acuity outcome in severe cases with the combined use of corticosteroids and antibiotics.2

|

|

Figure 7. Four-month follow-up: Macular OCT shows retinal thinning of the right eye compared to the left eye leading to decreased visual acuity in this patient. Click image to enlarge. |

The patient was ultimately treated with both doxycycline 100 mg BID for three months and rifampin 300 mg BID for six weeks. Any patient with suspected Bartonella henselae should be followed closely to monitor for improvement until complete resolution is shown. Generally, prognosis is good for most patients, who should achieve complete recovery and normal visual acuities within a few weeks to months after onset of symptoms.1 At the end of this patient’s treatment, she showed complete resolution of the left eye with no residual side effects. The right eye also showed complete resolution after additional doxycycline treatment with mild proteinaceous material remaining in the macula, but she sustained mild vision loss with a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/50. This decreased visual acuity correlates with the significant macular thinning as shown in Figure 7 as well as the flattening of the foveal contour in Figure 6.

|

|

Figure 8. Visual field of right eye (left image) showing superior temporal arcuate defect extending from optic nerve head correlating to area of myelination. Left eye (right image) shows scattered defects. Click image to enlarge. |

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the importance of considering multiple differentials for a patient who presents with bilateral neuroretinitis when Bartonella henselae is suspected. Blood work should be promptly completed to determine the cause of inflammation and initiate appropriate treatment as quickly as possible to allow for resolution and adequate visual prognosis.

1. Ksiaa I, Abroug N, Mahmoud A, et al. Update on Bartonella neuroretinitis. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):254-61. |