10th Annual Cornea ReportFrom advice on diagnosing and treating infections to managing trauma and limiting recurrent erosion, the April 2023 issue is full of clinical pearls to help you up your corneal management skills. Check out the other articles featured in this issue:

|

In any sporting event, knowing your opponent is the key to developing a game plan to defeat them. When you have a case of keratitis in your chair, the task is no different—you need a solid game plan to help your patient heal. Unfortunately, we, as doctors of optometry, don’t always know who our opponent is when the patient walks into the office. However, we do have plenty of previous game film on the most common causes of keratitis to rely on when planning our treatment approach. This is vital, as early, accurate diagnosis and treatment will improve the patient’s chances for a winning outcome.

Know Your Opponent

Before you can decide how to treat your opponent, or your patient, you must figure out if you are confronting an infectious or a non-infectious process. You’ll need a different set of plays lined up for an infectious presentation such as a bacterial keratitis secondary to Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus than you will for a corneal infiltrative event that can be managed with a topical corticosteroid or steroid/antibiotic combination drug. While the majority of infectious keratitis cases are microbial in nature, you need to keep fungi, viruses and parasites on your radar screens as potential offending pathogens.

As the majority of pathogens are unable to invade a structurally intact corneal epithelium, learning what was occurring before the patient decided to present is very important. Do they recall any trauma to the eye? If yes, what was it that hit or got in their eye? Dirt or vegetative matter greatly increases the chance you are dealing with a polymicrobial process with high risk of fungal infection. Do they work in a hospital or health care setting? If yes, you need to keep Methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) in your differential. Are they immunocompromised or diabetic, both of which increase their risk for infection? Do they have a history of oral herpes? Have they had similar episodes in the past? Last, but most importantly, are they a contact lens wearer? If so, are they caring for their lenses appropriately?

Your patient’s symptoms can help further guide your differential diagnosis. The degree of pain is usually greater when there is an epithelial defect present. Significant pain may point toward a microbial origin while less pain than might be expected for their clinical presentation could point toward a herpetic or acanthamoebic origin. The timing and progression of the pain is also informative. Pain that has been low to moderate and nagging is usually associated with a less virulent pathogen compared with acute symptoms that escalated quickly.

|

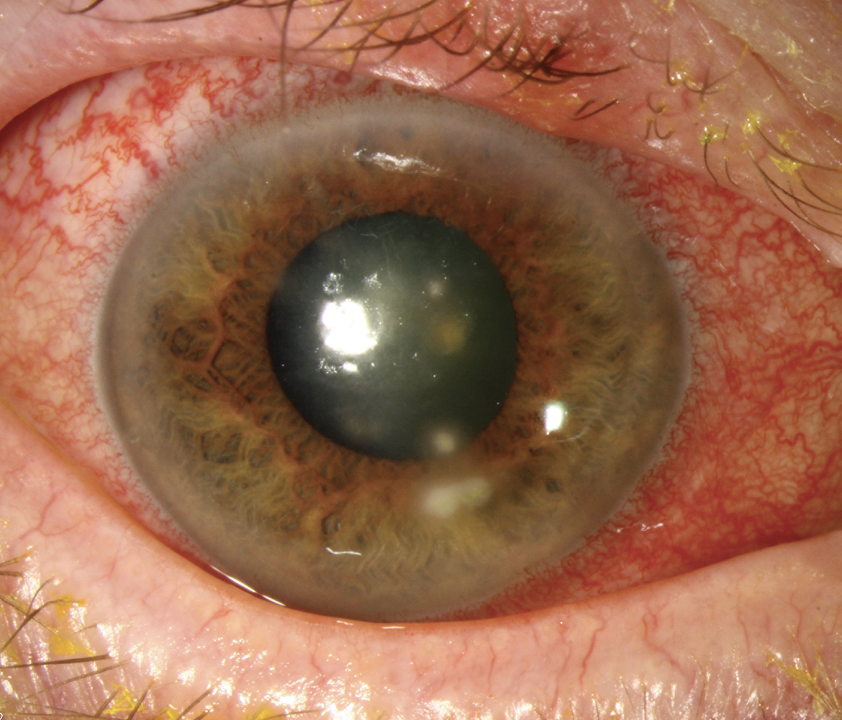

Fungal lesions tend to have dry, elevated infiltrates with feathery margins. This patient has a Fusarium ulcer. Click image to enlarge. |

Keratitis

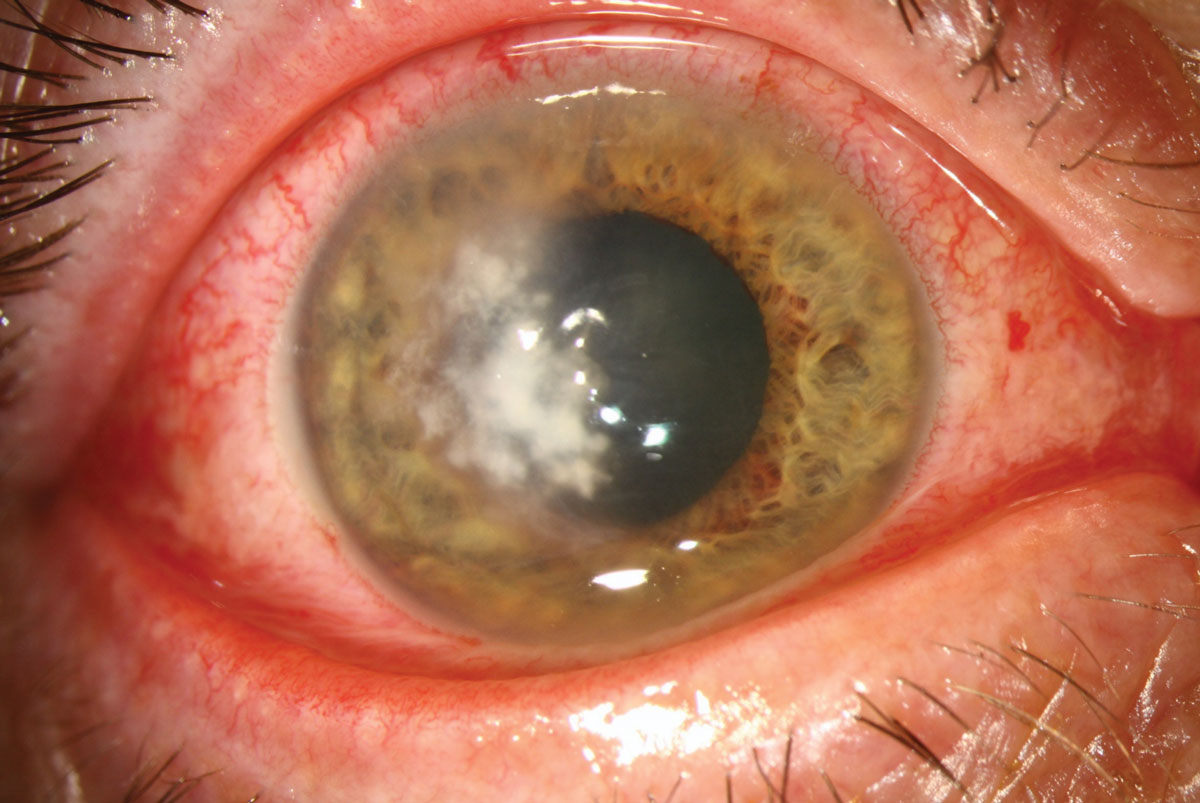

The vast majority of microbial keratitis cases are associated with contact lens wear. It is estimated that the incidence of microbial keratitis is 10 times higher in contact lens wearers compared to non-wearers.1 Improper care of lenses, extended wear and lens abuse are typically the cause of infection. Gram-negative Pseudomonas and gram-positive Staph. aureus are your major offenders in these situations. Pseudomonas, which readily attaches itself to the surface of a contact lens, requires rapid and aggressive treatment as it can penetrate the corneal stroma within days as it secretes proteases that induce stromal necrosis.

Carefully question contact lens wearing patients to determine if there has been any exposure of the eye, lens or storage case to water leading up to the infection. If there has been, Acanthamoeba must be in your differential. Acanthamoeba is a free-living amoeba and 85% of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) cases occur in contact lens wearers.

While you often hear about the ring-shaped infiltrate with AK, that finding actually does not present until late in the process, which often makes this a diagnosis of exclusion when antibiotic treatment proves ineffective. Early signs of AK include epithelial pseudodendrites, radial perineuritis with inflammatory cells surrounding the corneal nerves and a stromal appearance similar to stromal herpes simplex keratitis. While pain out of proportion to clinical signs is a common presentation with AK, some patients will present with little subjective symptoms.

Sizable differences exist in the prevalence of microorganisms endemic to the environment in different geographic locations. Gram-positive bacteria are more prevalent in northern California, the Northeast and mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. Gram-negative infections are more prevalent in Florida, Texas and central and southern California. Concerning fungal infections, yeasts such as Candida are more prevalent in colder, northern environments. Filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus and Fusarium are generally found in warmer, more humid southern environments.2

Examination. Once you gathered all of the patient’s history, have them sit behind the slit lamp and see what you are up against. Examination with both white light and sodium fluorescein is required. Infectious ulcers tend to present as a round epithelial defect with a corresponding stromal infiltrate of a similar size. An infiltrative presentation with minimal or no epithelial defect may be inflammatory as opposed to infectious. Pay attention to the depth of the lesion, as superficial defects have a better prognosis—either you’ve caught a bad actor early or the pathogen is less virulent. When the lesion is deeper in the stroma, the cascade of immune cellular pathways has likely begun. Inflammatory mediators and proteases promote the progression of the infection, enable tissue necrosis and impair healing.

Culture the eye. If you are lucky, the lesion is peripheral, potentially inflammatory in nature, but certainly less visually threatening. Central ulcers require you to make quick, more decisive treatment decisions. For the average OD in practice, any lesion on the visual axis and/or greater than 2mm to 3mm in diameter, especially with an associated anterior chamber reaction and significant stromal excavation, might be something not worth trying a “Hail Mary” to treat yourself. These eyes are at extremely high risk of visual loss and may best be treated by a tertiary care cornea specialist. Always have their number in the back of your playbook—that’s what they are there for.

If you want to treat eyes at this level of severity, you need to have the ability to culture the eye to identify the specific pathogen involved. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2018 Bacterial Keratitis Preferred Practice Pattern, while the majority of bacterial keratitis may be treated empirically, cultures are indicated in the following situations:3

(1) a corneal infiltrate is central, large (>2mm) and/or associated with significant stromal involvement or melting

(2) the infection is chronic in nature or unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy

(3) there is a history of corneal surgeries

(4) atypical clinical features are present that are suggestive of fungal, amoebic or mycobacterial keratitis

(5) infiltrates are in multiple locations on the cornea

Ideally, cultures are obtained prior to starting any form of antimicrobial therapy. Since it will take time for culture results to come back, you must initiate therapy empirically as the infection can progress rapidly without treatment. If you start empirical therapy and want to culture later, it can still be valuable, especially if your treatment does not seem effective.

|

Treatment. Whether treating empirically or while cultures are in process, starting with a broad-spectrum antibiotic such as a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone (gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, besifloxacin) is indicated. The fourth-gen agents have very good broad spectrum coverage against the most commonly encountered gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. Be cautious with third-generation fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin, as significant resistance is developing to this class of medication. If your patient has a large (>2mm diameter) or central ulcer, start them on a loading dose in the office (one drop every 10 minutes for one hour) and then have them instill one drop every hour for the next 24 hours.

While some doctors will prescribe an ointment in place of the drop when the patient goes to sleep, it is more beneficial to have the patient wake up every hour through the night and instill a drop of antibiotic. This level of compliance must be emphasized to the patient. If the ulcer is smaller or more peripherally located after the in-office loading dose, instilling an antibiotic every one to two hours while awake may be adequate. Use size, location and depth of the ulcer to make the decision on dosing frequency.

The most common reasons for failure are undertreatment or patient non-compliance with your treatment schedule. If a family member or acquaintance has brought the patient to your office, recruit them as a part of your treatment plan. If the patient is in significant pain and has an anterior chamber reaction, consider cyclopleging them to reduce their discomfort and to reduce the risk of posterior synechia development. Never patch the patient or apply a bandage contact lens, no matter how large the epithelial defect. Trapping the necrotic material from a microbial ulcer will keep the proteases and inflammatory mediators generated by the infectious process in contact with the stroma for a longer period of time, potentiating tissue damage and slowing healing.

Patients with suspected microbial ulcers must be seen daily. The amount of improvement you see within the first few days is inversely proportional to the severity at presentation. What you are watching for is any worsening of the infection in the first few days. An infection that is worsening on fluoroquinolone monotherapy may require addition of fortified antibiotics such as tobramycin 14mg/mL and/or vancomycin 10mg/mL to 25mg/mL. If necessary, be aggressive with these drugs, alternating them every 30 to 60 minutes around the clock.

If the eye is still not responsive, consider a 24-hour treatment break and culture the cornea for atypical pathogens. If you suspect MRSA as your offending agent based on the patient’s history (e.g., they work in a hospital, live in a nursing home or are immunocompromised), understand that fluoroquinolones are not terribly effective; consider going to vancomycin 25mg/mL to 50mg/mL more quickly. Culturing these suspect MRSA infections may also reveal sensitivities to older, more readily available antibiotics, such as bacitracin and gentamicin.4

Bringing a steroid drop off the bench when treating a microbial keratitis can be a controversial move. Steroids will help break the inflammatory cascade and reduce risk of scarring as the eye heals. According to the Steroids in Corneal Ulcers Trial, adding a steroid to quell inflammation has not been shown to significantly improve visual outcomes except in the most severe cases.5 That being said, many cornea specialists recommend delaying steroid use until the eye begins to show a positive response to your treatment, as steroids may worsen fungal, AK and herpes simplex infections. Keep your patient on antimicrobial therapy for several days and watch for signs of healing before considering adding a steroid.

|

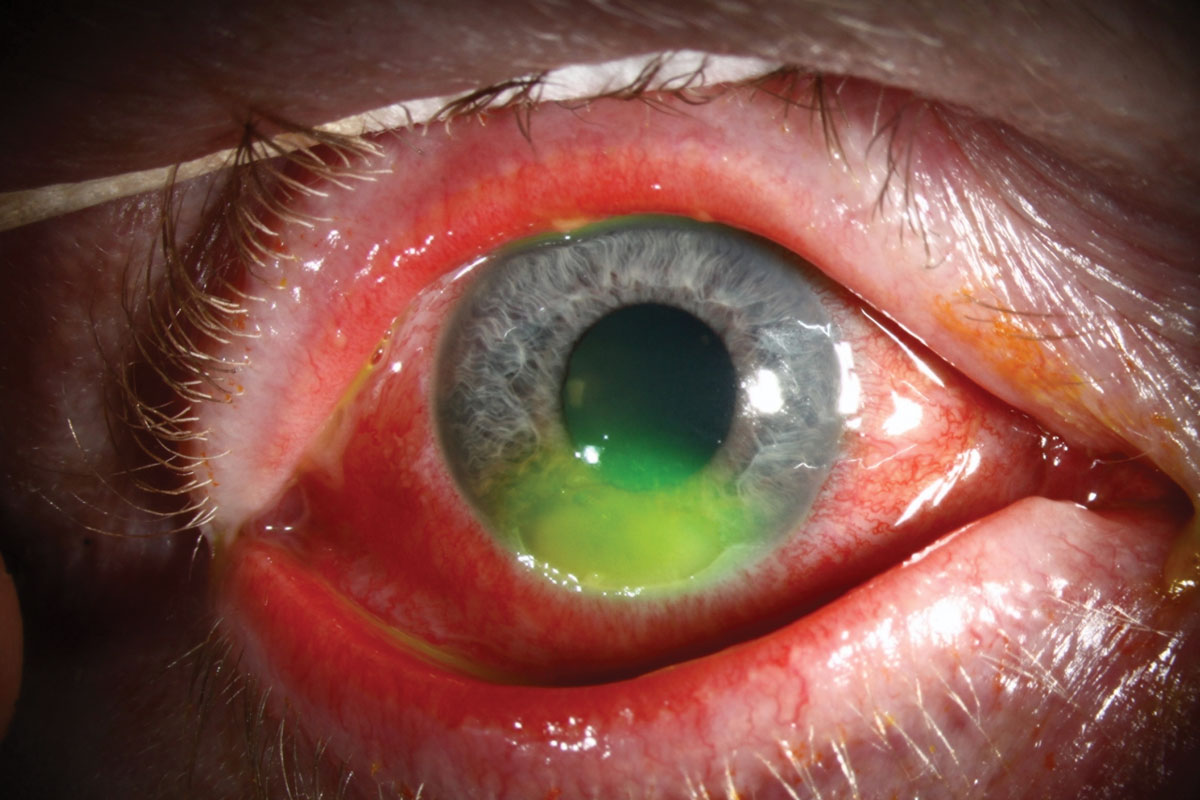

This patient has Pseudomonas keratitis. Given the higher risk of stromal damage in gram-negative bacterial infections, your treatment regmen should be appropriately aggressive. Click image to enlarge. |

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Keratitis

This is another differential in infectious keratitis cases. HSV keratitis can present in two basic forms: an epithelial variant, in which there is active, replicating virus present, and a stromal form that is an immune inflammatory response. Each form requires a very different game plan. A careful history asking about any recent labial cold sores or previous episodes of mild, persistent eye irritation can help narrow your diagnostic focus.

|

This patient has microbial keratitis after abrasion from a cockle burr. Any exposure to vegetative material raises the risk of polymicrobial infection. Click image to enlarge. |

Epithelial. This form of HSV keratitis often presents as a unilateral red eye with mild to moderate symptomatic irritation. It is often very easy to diagnose at the slit lamp when it presents with the classic dendriform lesion. However, HSV keratitis is known as the “great masquerader” because it may not have the easily identifiable lesion and become a diagnosis of exclusion. The central region of the tree-like branching dendritic lesions will stain with sodium fluorescein, as there is a frank, epithelial defect, and the borders will stain with rose bengal or lissamine green, as that is the location of the active viral infected cells.

Some HSV keratitis lesions are larger in size, similar to a bacterial ulcer, but with scalloped edges there is active viral infection. Use of both vital dyes is essential for the differential in these geographic HSV epithelial lesions. With either lesion morphology, reduced corneal sensitivity is an important finding.

As the virus is resident in the nerves in the trigeminal ganglion and corneal sensitivity is a function of trigeminal innervation, when the virus becomes active, it damages the nerves decreasing corneal sensitivity. When you are uncertain what you are looking at, pull a small wisp of cotton up from the end of a cotton-tipped swab and gently tap at the cornea. Do this with the non-affected eye first to see how the patient reacts, then test the affected eye. If you don’t see that reflexive twitch and blink, you have a hypoesthetic cornea. This explains why many eyes with HSV keratitis look worse than the patient’s symptoms might suggest.

Treatment. Topical and oral antivirals are used to treat the epithelial variant of HSK. Classic therapy is trifluridine 1% one drop nine times a day for seven days, decreasing to five times a day for no more than 21 days total if the epithelial defect is closed at that time. Use of trifluridine for over 21 days total can further damage the cornea due to its inherent cytotoxicity. Ganciclovir gel 0.15% can also be used five times a day until the epithelial defect is healed, then reduced to three times a day for seven days. It has less epithelial toxicity than trifluridine, but is often much more costly to the patient.

While not FDA approved, oral antivirals have been shown to be effective in the treatment of HSV epithelial keratitis.6 Acyclovir 400mg five times a day, valacyclovir 500mg two times a day and famciclovir 250mg two times a day all for seven to 10 days are potential oral routes of treatment for an acute infection. There is no evidence to support that using both a topical and oral antiviral is superior to either route of administration.7 The Herpetic Eye Disease Study also suggested that a long-term prophylactic dose of oral antivirals may be effective at reducing the rate of HSV keratitis recurrence. The prophylactic dose is one half the treatment dose for active disease.8 Steroids should never be used with a suspect HSV keratitis, as the virus replicates much more actively if the host cells are immunocompromised.

Stromal. This variant of HSV keratitis is less common that the epithelial variant and will present with a disc-shaped area of stromal edema with or without an overlying epithelial defect. The stromal variant is thought to represent a delayed cell-mediated immune response to previous epithelial HSV exposure and may follow an episode of frank HSV epithelial keratitis.

Treatment. Aggressive topical corticosteroids with oral antivirals are the treatment, specifically prednisolone acetate 1% drops six to eight times a day for at least 10 weeks with a very slow taper as the cornea heals is indicated.9 An oral antiviral at the same therapeutic dose as for the epithelial variant used concurrently with the corticosteroid has been shown to be effective. Prophylaxis with oral antivirals is indicated once the active infection has resolved.6

Stromal HSV keratitis with epithelial ulceration is rare and more difficult to manage. Topical corticosteroids are still the treatment of choice but must be used judiciously in the presence of an epithelial defect. Doubling the dosage of the oral antiviral is indicated for seven to 10 days. Patients with this variant are often better managed by a tertiary care corneal specialist.

|

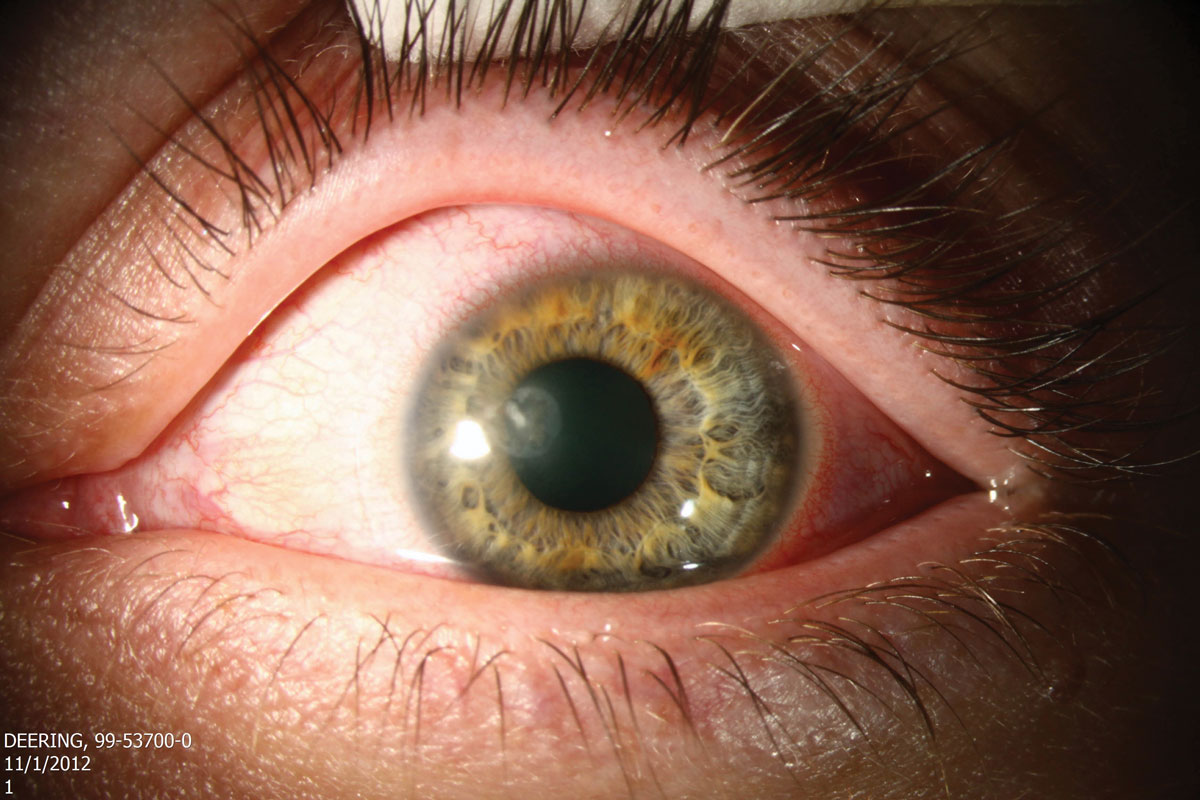

This patient has HSV keratitis with stromal infiltrates. Click image to enlarge. |

Fungal Keratitis

This will present in a similar fashion to a bacterial microbial keratitis. Fungal lesions tend to have dry, elevated infiltrates with feathery margins. You will often see multiple adjacent satellite lesions accompanying the primary lesion. If filamentous fungi such as Fusarium or Aspergillus are the causative organism, the infiltrate may have a dull, gray appearance in its early stages and progress to a lesion that looks more like an advanced bacterial ulcer. If yeasts such as Candida are involved, the lesions may have better defined borders and be smaller in size. Use your history to help determine if what you are seeing is fungal in nature.

|

|

Natamycin, the mainstay treatment for fungal keratitis, is not readily available at most retail pharmacies. Instead, seek out a pharmacy at a local medical center. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment. Natamycin ophthalmic suspension is the treatment of choice for a filamentary fungal infection.10 Natamycin is a polyene amphoteric macrolide antibiotic with antifungal properties and must be dosed according to the severity of the infection, ranging from every four to six hours to every one to two hours. More aggressive dosing is typically not required, as fungi do not replicate as quickly as do bacteria. Treatment may last over a month in some cases and should be continued beyond the observable healing of the corneal lesion. Know that natamycin is not readily available on the shelf of your local pharmacy, so consider reaching out to the pharmacy at a local medical center if it is needed. Often, they will have one or two bottles on hand, especially if they have an ophthalmology department. If you have a confirmed case of a yeast as the causative agent, compounded amphotericin B 0.15% may be the better drug of choice.11

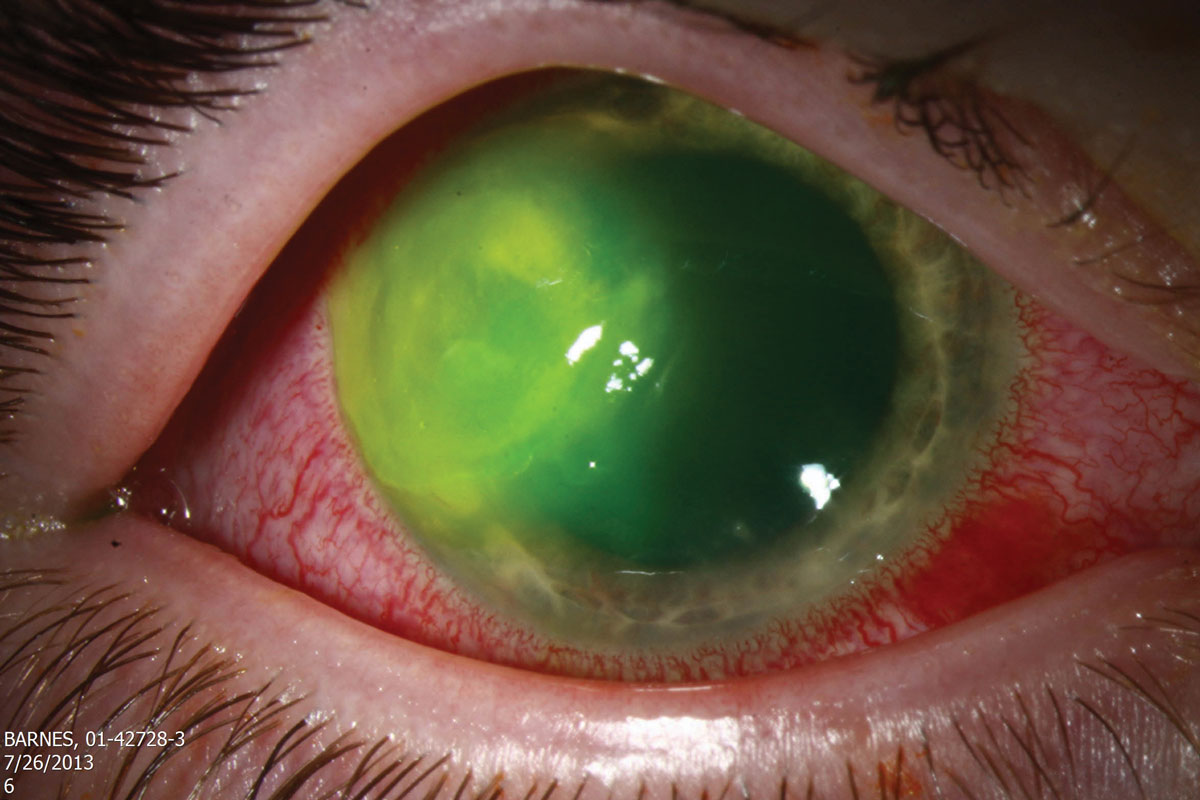

If you think your patient is presenting with an Acanthamoeba infection, traditional antibiotics are ineffective. It is always recommended that you obtain appropriate cultures to confirm that you are dealing with AK. First line treatments include the topical antiseptic biguanides polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.02% and chlorhexidine 0.02%. Both agents disrupt cytoplasmic membranes and are cysticidal. The biguanides are synergistic with diamidines propamidine isethionate (Brolene) 0.1% and hexamidine 0.1%. Diamidines denature cytoplasmic proteins and enzymes, inhibiting DNA synthesis. They are effective again both the trophozoite and cyst form of Acanthamoeba but can be more toxic to the corneal epithelium over time than the biguanides.12 Some corneal surgeons will opt to perform a superficial keratectomy prior to starting topical therapy to debulk as much of the organisms as possible. Topic treatment must be started hourly around the clock for the first 48 hours. The frequency of dosing is gradually reduced over days and weeks as resolution of the infection becomes apparent. Often patients are on topical treatment for four to six months and significant scarring is an end result, require a penetrating keratoplasty to restore functional vision.

|

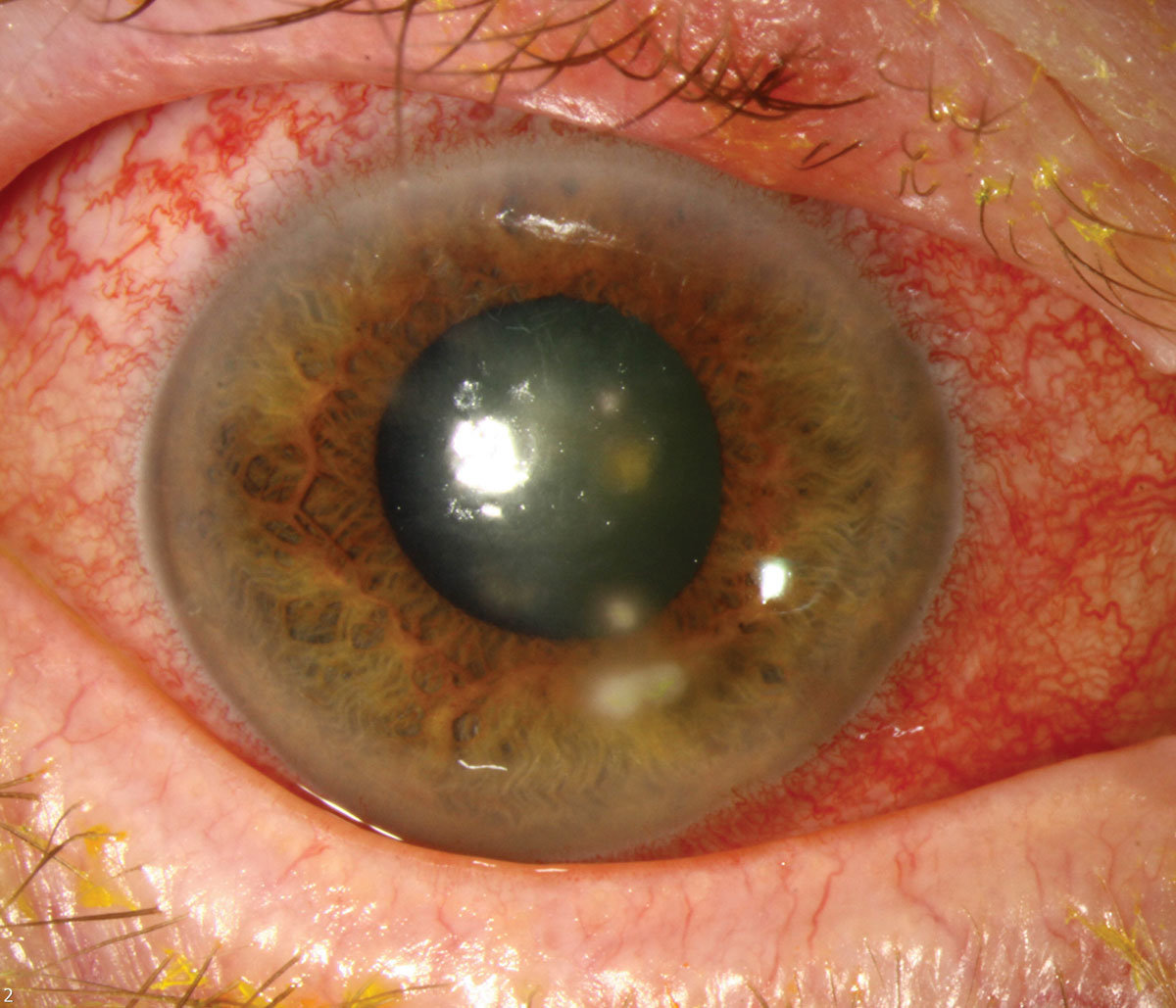

If diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis is delayed, the amoeba will have already penetrated further into the corneal stroma, which causes therapy to be more difficult. Click image to enlarge. |

Takeaways

Before implementing a treatment plan, you must be certain of your opponent. It is often said in health care that the treatment is easy, it’s the diagnosis that is difficult. Use your clinical acumen to carefully assess the situation before initiating treatment. Having an assortment of game plans ready to implement once you’ve made your diagnosis is key to providing the best care possible for your patients

1. Durand ML, Barshak MD, Chodosh J. Infectious keratitis in 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(13):1319-20. 2. Estopinal CB, Ewald MD. Geographic disparities in the etiology of bacterial and fungal keratitis in the United States of America. Sem in Ophthal. 2016,31(4):345-52. 3. Lin A, Rhee MK, Akpek EK, et al. Bacterial keratitis preferred practice pattern. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):1-55. 4. Confronting corneal ulcers. EyeNet Magazine. www.aao.org/eyenet/article/confronting-corneal-ulcers?july-2012. July 2012. Accessed January 29, 2023. 5. Srinivasa M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, et al. Corticosteroids for bacterial keratitis: The Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT). Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(3):143-50. 6. White ML, Chodosh J. Herpes simplex virus keratitis: a treatment guideline. American Academy of Ophthalmology Compendium of Evidence-based Eye Care. June 2014. 7. A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for prevention of stromal keratitis or iritis in patients with herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(6):703-12. 8. Wilhelmus KR, Beck RW, Moke PS, et al. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex eye disease. N Engl J Med. 1998:335(5):300-6. 9. Wilhelmus KR, Gee L, Hauck WW et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study: A controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(12):1883-95; discussion 1895-6. 10. Cabrera-Aguas M, Khoo P, Watson SL. Infectious keratitis: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;50:543-62. 11. Thomas PA. Fungal infections of the cornea. Eye. 2003;17:852-62. 12. Maycock NJR, Jayaswal R. Update on acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Cornea. 2016;35:713-20. |