As optometry grows at an impressive rate—new grads outpace retirees every year—it becomes more difficult to stand out from the crowd. If yours is a typical practice, what draws patients in beside proximity and the insurance plans you accept? Those may have been enough to help you get by in the past. But sooner or later, you will need more.

There are plenty of ways ODs can spice up their practices. You could buy that expensive piece of equipment you have been eyeing. Perhaps you could look into bringing a ground-breaking new treatment or another doctor on board. Maybe you could even add a specialty.

Specializing allows ODs to differentiate and expand their practices, increase their profit margins and meet more patient needs. Some specialties build on the services a practice already offers. Others completely reinvent a practice. But all come with a few basic requirements.

Practice management guru Gary Gerber, OD, of Treehouse Eyes and the Power Practice, says integrating a specialty into a primary care practice should be done carefully and with plenty of forethought to ensure positive clinical outcomes.

Dr. Gerber says the biggest lesson he has learned and continues to preach is that clinicians interested in specializing cannot dabble. You will be doing your patients and specialty more harm than good, he says, because dabbling prevents patients from receiving the quality of care they need. If you are going to call yourself a specialist, you better make sure you can live up to the title.

Clinicians must learn the ins and outs of the trade and its patient demographic, and staff must be appropriately trained as well, according to Dr. Gerber. You must also understand the time commitment, the equipment investment and the billing process, he notes. By putting in the work before providing care, Dr. Gerber says clinicians are able to plan ahead, better manage and balance competing priorities and pave the way for a successful specialty practice without disrupting the current establishment.

This article discusses several specialties and the fundamental steps clinicians can take to master each, beginning with simpler undertakings and progressing to some of the more ambitious pursuits. What makes one easier to integrate than another? Minimal added expense for maximum gain, services that appeal to abroad swathe of patients and clinical services that build on your existing knowledge base.

|

| Paul Karpecki, OD, performs a slit lamp exam on a dry eye patient. An early interest in dry eye led Dr. Karpecki to devote much of his professional career to the discipline, helping him make a name for himself. Photo: Paul Karpecki, OD |

Dry Eye

Nearly 35% of Americans are affected by dry eye, according to Peter Cass, OD, of Beaumont, TX, and Nevada’s Douglas Devries, OD. This number, however, is conservative because symptoms are misjudged, hard to understand and easily confused with those of other conditions, the doctors noted during their lecture on starting a dry eye clinic at the AOA annual conference in Denver earlier this year.

While the percentage of the population affected by dry eye is increasing, Jennifer Lyerly, OD, of Cary, NC, says clinicians rely on the same simple solutions—like prescribing artificial tears and daily disposable lenses—and fail to provide personalized care that offers long-term relief.

Drs. Cass and Devries argue that specializing in dry eye is cost-effective, is profitable and pays for itself.

To properly motivate a dry eye patient to comply with treatment regimens and prevention strategies, it is important to first educate all members of a practice about dry eye so they can facilitate effective patient education, according to Dr. Lyerly. She adds that tasks should be delegated; technicians must be able to explain the purpose and function of different devices, take images and perform treatment procedures, while clinicians are in charge of identifying candidates for treatment and interpreting images.

Dr. Lyerly suggests focusing on the high rate of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) among patients—a study suggests 86% of dry eye patients have associated MGD—by investing in devices that photograph and treat the glands.1 TearScience’s LipiView and LipiScan meibographers and LipiFlow treatment device, BlephEx (Rysurg), intense pulsed light and MiBo Thermoflo (MiBo Medical Group) are all used by specialists to treat MGD, says Dr. Lyerly.

Once your office is geared up and your staff is trained, Drs. Cass and Devries note that specialists should standardize the process of screening and examining patients with a questionnaire like the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED), which quickly evaluates the frequency and severity of symptoms on a scale from 0 to 28, 0 indicating the least severe form of the disease. These patients will likely need long-term clinical observation and care, so establishing baselines is important for measuring progress.

|

| Dr. Collier helps a specialty contact lens patient insert a custom lens. Photo: Cory Collier, OD |

Specialty Contact Lenses

Fitting custom lenses builds practices, increases referrals, better serves an existing yet underserved patient population and is rewarding on a personal and professional level, says Cory Collier, OD, of Lakewood Ranch, FL. It is also an extension of a clinician’s ability to manage corneal and ocular surface conditions.

Many specialty contact lens patients have medical conditions that require separate follow-up care and management, creating additional streams of revenue, according to Dr. Collier. It is also an ideal way to insulate your practice from the commodification of soft contact lenses that causes patients to look toward online lens suppliers.

Dr. Collier recommends clinicians gain as much knowledge about specialty lenses as possible prior to investing their time, money and resources into building a practice that may not be of any personal interest or value to them. Brooke Messer, OD, of Edina, MN, says clinicians can do so by making connections, forming relationships and taking advantage of resources, such as conferences and CE courses.

Dr. Messer suggests establishing a rapport with specialty lens labs and their consultants to learn more, understand the warranty process and order the right products for a larger number of patients. Dr. Collier says one of the biggest mistakes he sees is when a specialist acquires a little bit of knowledge about many products rather than a lot of knowledge about a few products. He suggests honing your craft on a lens design you understand and making it your “primary weapon” so you can become an expert in one thing instead of a generalist in a lot of things.

To provide quality care, the entire practice needs to be on board. Staff must be trained and prepared to interact with different patient groups and ocular conditions and educate patients about lenses, fitting and wear and care, says Dr. Messer. Maybe most importantly, staff needs to understand how custom lenses benefit the patient and the practice, notes Dr. Collier.

Because most primary care offices already have the fundamentals, Dr. Collier says the equipment investment is minimal. To ensure a practice has the necessary tools, Dr. Messer notes that it is worth investing in a corneal topographer, an OCT capable of anterior segment imaging and a specular endothelial microscope. You will also need fitting sets for GPs and scleral lenses.

When acquiring patients, Dr. Collier suggests using a mixture of internal and external marketing strategies. Staff must be able to identify candidates from their current patient pool and educate clinicians who do not offer specialty contact lens services, or work with those who do, on the signs of a specialty lens patient, he says.

Dr. Collier recommends reserving initial visits for consults to assess a patient’s condition, and educate them about it and the process so both parties feel comfortable, are on the same page and have similar expectations. Basic fitting and lens information, tips, resources, costs and responsibilities should be outlined in a brochure or contract, and patients should be given the chance to ask questions and express concerns, notes Dr. Messer.

When beginning the process of fitting custom lenses, Dr. Messer says it is smart to start with and learn from patients who have a milder version of the condition for which they are being treated. Only after a clinician completes more fittings and masters the common symptoms of less severe conditions should they start treating conditions that have progressed, according to Dr. Messer.

Each specialist determines their own fitting fee, which could amount to several hundred dollars, and how much to mark up their lenses based on the value they place on their time and expertise, says Dr. Collier.

|

| Dr. Elliott performs retinoscopy on a baby that remains in a car seat to ensure a smoother exam. Photo: Kathleen Foster Elliott, OD |

Pediatrics

One in four children has an undiagnosed vision problem that could lead to adverse effects ranging from chronic headaches to school difficulties, according to the AOA.2 Kathleen Foster Elliott, OD, of Tulsa, OK, says caring for these underserved patients is important because 80% of learning occurs visually, and untreated vision problems in children could be life-threatening.

Specializing in pediatrics is also low-cost and profitable, Dr. Elliott notes, because most primary care offices already have the necessary equipment, and clinicians are able to schedule family members and more appointments of shorter lengths.

However, to treat this young patient demographic, staff must be trained to interact with children and educate parents, according to Dr. Elliott. Accommodating kids can be tricky; they need their own waiting room amenities (toys, coloring books, videos, kid-sized chairs), appropriate diagnostic equipment—and unconditional patience from everyone in the office.

When stocking their practices with appropriate frame sizes, designs and brands, Dr. Elliott says clinicians should take into account the flat nose bridges typical of children. Along the same lines, she notes that clinicians should be mindful of purchasing tools suited for young patient care, including cyclopentolate eye drops to ascertain an exact prescription and lens bars to perform retinoscopy. Dr. Elliott also recommends investing in the Spot Vision Screener (Welch Allyn), which can serve as a portable autorefractor for adults, to pick up early signs of amblyopia, refractive error, strabismus and astigmatism in patients as young as newborns. Using their newly acquired equipment, Dr. Elliott notes that specialists will be able to perform appropriate exams, such as a cycloplegic exam to obtain an accurate refraction and diagnose accordingly.

Due to children’s short attention spans, Dr. Elliott suggests performing eye exams in an infant and toddler room and keeping patients occupied with toys or cartoons on a laptop or the Acuity Pro (VisionScience Software), which also enables clinicians to use an eye chart. Dr. Elliott recommends letting young kids sit on their parents’ laps and keeping babies in their car seats to accommodate them comfortably and alleviate fear. Pending parental approval, Dr. Elliott says clinicians could implement a reward system for children who are on their best behavior throughout the exam.

Dr. Elliott recommends specialists develop relationships with local family doctors and pediatricians to educate them on when to refer, raise awareness about their pediatric services and improve patient flow.

|

| To improve their peripheral vision, a patient may use a Marsden Ball during therapy. Photo: Heidi Sensenig, OD |

Vision Therapy

Adding this specialty can differentiate your practice as a referral center, expand your patient base, add an income stream and better serve existing patients, according to Heidi Sensenig, OD, of Reading, PA. Vision therapy is unique because it is one of a few eye specialties that only ODs learn in school, notes Rima Bakhru, OD, of Park Slope Eye. MDs are simply not a competitive factor, and honestly, most ODs are not either; the field is small.

Dr. Sensenig says changing lives for the better and success stories—including a 10-year-old boy who earned his first A on a reading test and a 28-year-old woman who is able to play with her son without getting a headache for the first time since her concussion—are the most compelling reasons to specialize in vision therapy.

To become an expert, Dr. Bakhru suggests clinicians find a specialist to shadow or complete an in-state residency to better understand the specific model. Clinicians can also connect with other practitioners and expand their knowledge through CE courses, Dr. Sensenig notes. Understanding vision therapy from the inside out is especially important if a clinician plans on working with traumatic brain injury patients.

As soon as a clinician has the specialty knowledge they need, they are ready to join a practice interested in vision therapy. Some doctors do their own vision therapy, Dr. Sensenig says, while others hire vision therapists. According to Dr. Bakhru, vision therapy in a private practice is only profitable if a therapist sees patients while a specialist performs exams and evaluations, or if the specialist sees multiple patients at once for therapy.

If a vision therapist is brought on board, they must be trained to care for patients under the direction of the specialist, says Dr. Sensenig. One way they can master their trade is by shadowing the specialist or another vision therapist, notes Dr. Bakhru.

As vision therapy is integrated, Dr. Bakhru recommends holding staff meetings to ensure all members of the practice understand therapy programs and billing processes.

Although specializing in vision therapy requires an investment in equipment, Dr. Sensenig notes that a practice can start with the basics and add products and equipment as necessary down the road. Dr. Bakhru suggests purchasing flippers, prisms and vectograms and looking into modern technology, including the Sanet Vision Integrator (HTS Vision), the Computer Orthoptics VTS4 (HTS Vision) and virtual reality accessories from Vivid Vision. A one-time equipment cost of around $30,000 quickly pays for itself, and the revenue from therapy sessions, products, exams and evaluations increases the profitability of becoming a vision therapy specialist, according to Dr. Bakhru.

Dr. Bakhru notes that it is important to carefully design room features—window placement, chair type, equipment setup—when considering treatment effectiveness in spaces where clinicians care for patients. She recommends using clear doors so parents can check on and reassure their children.

Dr. Sensenig suggests hiring someone who can effectively market your practice and optimize your website, social media pages and general internet presence. In addition, Dr. Bakhru recommends visiting local schools and doctors’ offices to raise awareness about your services and educate staff on the signs and symptoms of a child experiencing binocular vision problems so they are able to point them in the right direction.

Patient education should begin during the initial evaluation, says Dr. Bakhru. She recommends explaining the therapy process in a simple, reassuring way to the parent and the child while performing the exam. Letting parents watch the exam and see the results helps convince them that therapy is necessary to correct their child’s vision problems, notes Dr. Bakhru.

According to Dr. Sensenig, one of the most important parts of opening a vision therapy clinic is creating an environment where patients feel at home and comfortable that their needs are the first priority. Dr. Bakhru says identifying with patients on a personal level and tailoring the therapy process to their interests and needs goes a long way toward making a successful experience possible.

|

| Dr. Diecidue reviews an OCT scan of the retina for any indications of diabetic retinopathy. Photo: Anthony Diecidue, OD |

Diabetes

Data from the World Health Organization shows that nearly 425 million people worldwide have diabetes, and that is not even including those who have prediabetes.3 Paul Chous, OD, of Tacoma, WA, adds that at least half of many offices’ patients could have abnormal blood glucose levels and be at significant risk of developing diabetes-related eye diseases.

As the number of prediabetic and diabetic patients and the demand for services grows, so does the profitability of specializing in diabetes, notes Ansel Johnson, OD, of Blue Island, IL.

To acquire the necessary knowledge, Dr. Johnson suggests finding a mentor and joining the American Association of Diabetes Educators.

Dr. Chous notes that while the majority of diabetes equipment is low-cost, most primary care offices already have the basics. He says investing in imaging technology gives clinicians the ability to detect ocular changes caused by diabetes earlier and predict the onset of associated eye diseases. Dr. Johnson recommends purchasing an OCT, extended color vision testing, a central VF, an ERG and nutritional supplements.

This specialty is tougher than some others because clinicians need to be adept at spotting early diabetic retinopathy, and their knowledge of systemic health and endocrine function must go above and beyond what is expected in general optometric care. It also puts the pressure on you to be the quarterback of care among the patient’s general practitioner, endocrinologist and retina specialist.

Dr. Johnson says taking advantage of the training manufacturers offer staff and the information they give patients helps practices and patients alike understand diabetes and its ocular effects. He recommends providing additional information and further educating patients through handouts and conversations.

Dr. Chous suggests clinicians advertise the services they are offering to current patients and other diabetes care providers to attract a larger patient base. When treating patients, Dr. Chous says it is important to help those who are high-risk monitor and reduce modifiable risk factors—such as what they eat and drink, how often they exercise and how many hours they sleep—and pay attention to factors—including glycosylated hemoglobin levels, duration of poor glucose control and insulin use—that increase the risk of eye diseases like diabetic retinopathy and macular edema.

|

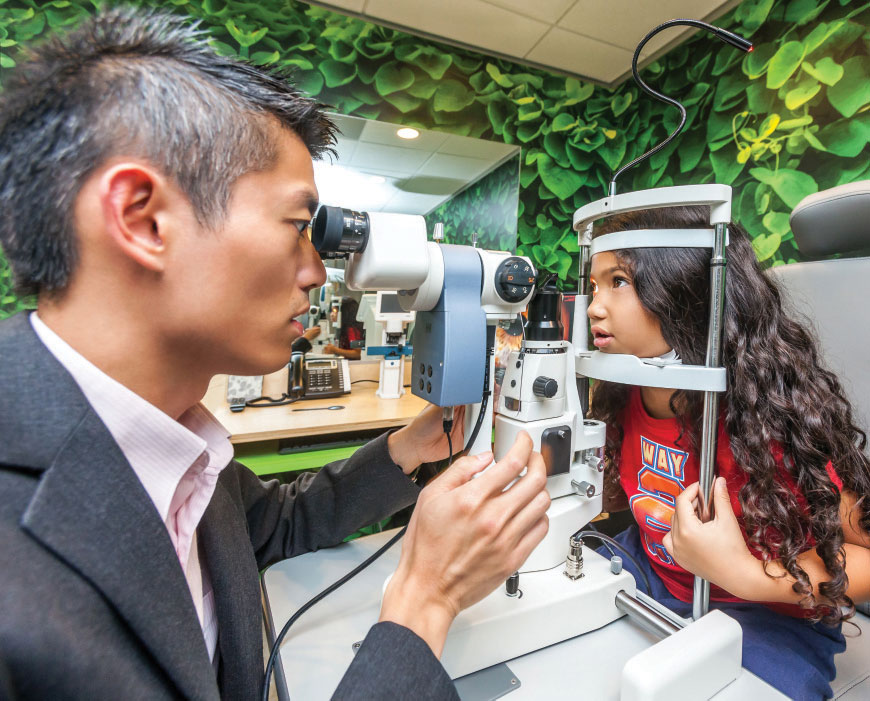

| Dr. Chan examines a young myope. Photo: Gary Gerber, OD |

Myopia Management

This one shouldn’t be hard to specialize in, right? Wrong. The stakes are higher than you may realize and it’s a time-consuming endeavor.

One in four, or 10 million, children in the United States is myopic, according to Kevin Chan, OD, of Treehouse Eyes. Dr. Chan notes that childhood myopia is seen so often that clinicians usually default to advising parents to order a stronger prescription for their child—a temporary remedy for clearer vision before the child’s prescription changes again. Relying on this course of action may do kids a clinical disservice, says Dr. Chan, and can potentially put them at an increased risk of irreversible ocular consequences like myopic retinal detachment in adulthood.

As the number of myopic patients increases—a study suggests half of the global population will be myopic by 2050—so does the need for specialized care.4 Myopia management, however, is time-consuming and requires unique expertise, technology and resources, according to Dr. Chan. He advises clinicians who want to commit to managing myopia to be prepared to give up other areas of their practices to ensure quality care and patient satisfaction. Dr. Gerber says untreated progressive myopia may come with clinical consequences, and dabbling only reinforces the problem and its risks.

The first order of business is learning everything there is to know about myopia management from the clinical and business perspectives, according to Dr. Gerber. Staff must be trained to explain myopia and its treatment options to parents, he says. He adds that it is important for specialists to be proactive about communication so they can keep parents informed and up-to-date on options for their children.

Clinicians must then obtain technology that helps meet the goal of myopia management: slowing down axial length growth. Dr. Chan says quality technology can objectively measure changes in axial length to a finer degree. He adds that having a reliable, accurate and reproducible way of measuring length helps demonstrate how well a treatment is working. Dr. Chan recommends clinicians invest in a corneal topographer and look into open field autorefraction, peripheral autorefraction and wavefront aberrometry.

To acquire patients and establish a reputation, Dr. Chan suggests combining social and digital marketing, using testimonials, treating local physicians’ kids and doing consumer research. Because there are no FDA-approved treatments at this time, Dr. Gerber says an attorney who specializes in healthcare and consumer law should vet all marketing ideas.

Dr. Chan says thorough myopia management consultations and assessments could take at least an hour with parent discussions adding half an hour, while follow-ups could take twice as long as routine contact lens appointments. Ultimately, Dr. Gerber says the time spent caring for a myopic patient amounts to six to eight times the time spent caring for a regular patient. For these reasons, Dr. Chan encourages clinicians to schedule appointments for myopic patients on the same days.

Due to a lack of understanding about the consequences of myopia, Dr. Chan notes that it is important to communicate the differences between refractive changes and eye complications with patients and parents and focus on the long-term benefits of myopia treatment. He also suggests specialists conduct pre-testing for younger patients instead of technicians to engage young, anxious patients and establish a rapport.

|

| In a glaucoma specialty practice, a handheld tonometer makes taking IOP readings a breeze. Photo: Nathan Stevens, OD |

Glaucoma

About half of patients with glaucoma are undiagnosed and undertreated, according to Eric Schmidt, OD, of Omni Eye Specialists. As the prevalence of glaucoma grows with an aging population, he says ODs will have to step in to satisfy the larger demand for treatment.

Dr. Schmidt adds that glaucoma practices are profit centers because each patient is seen so frequently and requires consistent testing.

Because the need for services is increasing and the majority of practices already see glaucoma patients, Dr. Schmidt suggests group practices appoint the doctor most knowledgeable about glaucoma as the specialist. He recommends acquiring knowledge and hands-on experience through a mentorship or fellowship. Dr. Schmidt adds that students who are interested in specializing in glaucoma should complete a residency to witness care protocols for every form of the disease—from how it presents to how it progresses to medical and surgical management. Specialists can continue to acquire knowledge and brush up on their skills through programs and CE courses, he notes.

Dr. Schmidt recommends allocating time and resources to train and educate staff on what glaucoma is, whom it affects and its blinding nature. He says technicians or assistants should be hired and trained to administer tests and explain the importance of eye drops, compliance and follow-up to patients.

Starting a glaucoma practice is costly, as investing in the right equipment to properly treat patients is key. According to Deepak Gupta, OD, of Milford, CT, spending between $50,000 and $60,000 on the first round of purchases buys an applanation tonometer, a gonioscope, a fundus camera and a threshold VF analyzer. Dr. Gupta also recommends investing in a nerve fiber analyzer—an OCT costs between $60,000 and $80,000—and a corneal pachymeter.

To begin the patient acquisition process, Dr. Schmidt notes that specialists should broadcast their services to current patients and local practices. He says it is important to establish your specialty practice as safe and trustworthy when setting it apart from others and encouraging referrals from doctors.

Dr. Schmidt says the hardest part of treating glaucoma is ensuring patients understand the disease and its sight-threatening implications. Educating patients through conversations, brochures and videos is important for compliance; patients who understand the sight-threatening nature are more likely to adhere to treatment and see better results.

|

| This elderly patient wears bioptics to drive, but is more independent and self-sufficient as a result. Photo: Richard Shuldiner, OD |

Low Vision

Some would argue that this specialty should be listed first, as every practice has patients not correctable to 20/20 who yearn to see better. Leaving no stone unturned in the pursuit of better vision is also a fundamental part of what it means to be an OD. Yet low vision remains intimidating to many, sometimes out of concerns that it is too much work or fear of interprofessional friction as doctors compete for patients. Inadequate insurance coverage for visual aids also adds complexity to the experience, as out-of-pocket costs for patients can sometimes be high.

Beside the overwhelming need for services—research shows that just under 255 million people worldwide suffer from vision impairment— Richard Shuldiner, OD, of Corona, CA, says reasons to specialize in low vision include the professional satisfaction of helping someone who feels helpless, the ability to build and differentiate your practice and the financial rewards.5 To reap the benefits, however, clinicians have to know where to start. This is where things get challenging.

Dr. Shuldiner says specializing in low vision is difficult because there is no standard process. At the very least, specialists must be able to conduct low vision exams, be knowledgeable about rehabilitation devices and techniques and understand what it takes to be a low vision doctor and care for patients with vision impairment, according to Dr. Shuldiner. He adds that it is important to shadow local experts and take advantage of learning opportunities to ensure the best, most efficient quality of care.

Staff must have a similar comprehension of low vision to answer questions, provide information and promote patient satisfaction and a reputabe practice, says Alexis Malkin, OD, of Baltimore, MD.

Specialists should put their newly acquired knowledge to work by purchasing low vision equipment for their offices. Dr. Malkin says essential items include an ETDRS chart, a contrast sensitivity chart, a continuous text reading card, materials to test patients’ spot reading abilities and visual-assistive equipment.

Dr. Shuldiner recommends clinicians market their specialty practices to the public rather than eye care providers so patients know what low vision is and that services exist and are available.

Once a patient expresses an interest in low vision services, Dr. Shuldiner notes it is then up to the specialist to determine if the patient qualifies for and can be helped by low vision care and set practical expectations of cost, options and what can and cannot be done. Dr. Malkin adds that patients must report their functional history, which measures the impact of vision impairment on reading, visual information and sight, mobility, daily activities and driving.

After qualifying a patient, Dr. Shuldiner then performs a one-hour exam and prescribes a custom-made device, such as a telescope, microscope, prism or filter.

Specialists bill for visits based on time spent interacting with patients rather than medical complexity, notes Dr. Malkin. Medicare covers low vision as a rehabilitation service for patients with medical diagnoses, but Dr. Malkin says patients must pay for the refraction cost. Thus, she adds that it is important to discuss all options and coverage plans with patients.

Follow Your Bliss

These specialty focuses are by no means an exhaustive list. In a sense, anything can become a specialty if you care enough about it.

Provided you are passionate about pursuing a specialty and have access to a large enough patient population to make becoming a specialist financially worthwhile, you will be well on your way to carving out a niche in your practice in no time.

1. Nichols KK, Foulks GN, Bron AJ, et al. The international workshop on meibomian glan dysfunction: executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1922-9. 2. American Optometric Association. School days: time for comprehensive eye exams. www.airoptix.com/contact-technology.shtml#ultra-smooth. Accessed September 15, 2018. 3. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1513-30. 4. Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):1036-42. 5. Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, et al. Magnitude, temporal trends and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(9):888-97. |