It is estimated that more than one in five adults 18 and older in the United States live with a mental illness—nearly 57.8 million, representing 22.8% of all adults—and this increases to nearly 50% for adolescents.1 Given these staggering statistics, ODs will see psychological issues in the exam chair often, and points to why our role of screening and participation in full-scope care is critical for our patients.

We are not trained psychotherapists, but as primary care physicians (PCPs) for the eye, how do we navigate these issues that manifest in our patients during an exam? As an OD turned psychotherapist, I’m going to help answer this question and provide suggestions to address and defuse psychological issues when they happen.

Intake Forms

We have medical conditions and the medications that go along with them on our intake forms. It is important that we have a place on the form to write down psychological conditions and the psychotropic medications our patients are taking. As ODs, this gives us a useful snapshot of the mental health conditions our patients have, which can help us anticipate some of the issues that may come up during the exam.

Taking it a step further, we could also have patients fill out short mental health screening tools—GAD-7 for anxiety and PHQ-9 for depression, as examples—both of which many PCPs use now.

To illustrate this, let’s talk about bipolar disorder and one medication our patients may be taking for this condition, lithium. If you have a new patient who lists bipolar disorder on the intake form and takes lithium, what should you be on the lookout for? This medication may cause eye irritation and dry eye during the first few weeks of treatment. A contributing factor is that lithium can increase sodium concentration in the tear film. Knowing this can prompt you to check tear film osmolarity and treat the underlying irritation while the patient is adjusting to lithium.2There are other ocular side effects of psychotropic medications, and optometrists should follow individuals placed on agents such as this and antidepressants diligently. A standardized approach for monitoring ocular toxicities from these medications and others would be helpful.2

|

| Be aware of certain psychotrophic medications that can cause ocular side effects. Photo: Getty Images. Click image to enlarge. |

Basic Awareness

So, you have a mental health section on your intake form—now what? Start to recognize the importance of encountering and caring for patients with mental health conditions, the medications that go with them and their ocular side effects. These include:

- Anxiety disorders/depression.

- Phobias.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- ADHD.

- Schizophrenia.

- Substance-related and addictive disorders.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorders.

- Abuse in children, the elderly and those with a disability.

While this is not an exhaustive list, basic knowledge of these major conditions will set you up well to navigate psychological issues that may come up. Let’s take a look at each of the mental health conditions above and how they may manifest in your exam chair:

Anxiety disorders/depression. Research shows that patients with retinitis pigmentosa, keratoconus, Sjögren’s syndrome and glaucoma have higher levels of anxiety and/or depression than age-matched controls.3-6 How does knowing this help us as optometrists? Let’s say you have a patient with keratoconus and you are the third OD they have seen because not one has provided a reason for their fluctuating vision loss. They appear nervous, sad and frustrated, and their responses are very short. Knowing that patients with keratoconus can have higher levels of anxiety and depression allows you to anticipate how they might present ahead of time and tailor how you interact with them as a result.

Ask more open-ended questions to get them talking more and validate their frustration so they feel heard. Allay their anxiety by answering any questions they have and let them know you will do your best to help them, rather than just jumping into the exam. Yes, this is basic rapport building, but taking a bit more time and care in engaging can go a long way in reducing their anxiety, helping them feel more comfortable with you.

As a psychotherapist at a university counseling center, I had a keratoconus patient referred to me for anxiety and depression by an OD who worked at the same clinic. It turns out the client had suicidal ideation, until they were referred by that OD for corneal crosslinking. Prior to that, the patient had seen several optometrists and ophthalmologists who were not able to help and the patient was severely depressed because they felt unheard and hopeless that their vision would never improve. The OD in this case not only made the right referral for corneal crosslinking, but may have saved this patient’s life by referring for therapy.

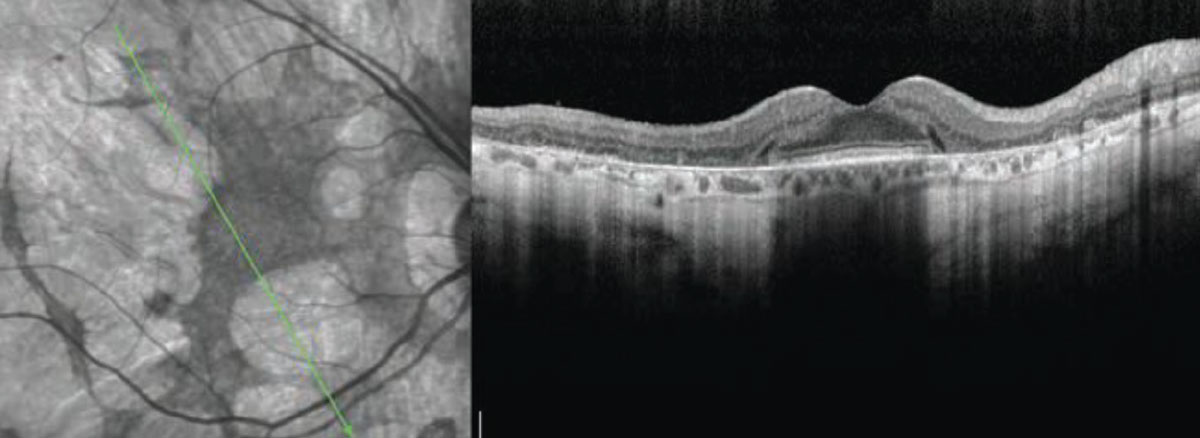

|

|

A 54-year-old Black female with pertinent history of clozapine 100mg PO daily use for schizophrenia. No previous history of typical antipsychotic medication use. Her best-corrected visual acuity is 20/20 OU. Note the fine golden-brown dust-like deposits on the corneal endothelium, greatest inferiorly and anterior subcapsular opacity in a stellate pattern in both eyes. No pigmentary retinopathy was noted. Photo: Bhawan Minhas, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Phobias. As an optometrist, I had a new patient who told me he had a phobia of being dilated, which I had never heard of at the time. He explained that when doctors tried to dilate him, he’d get extremely anxious and fearful. I asked him if he was willing to try it again—taking it slow—and he agreed. I told him I would start with a drop of an artificial tear to see how that felt before instilling the first dilation drop; this made him feel comfortable with me. The patient then started to feel anxious and I reassured him that it was just an artificial tear with no medication in it, and he calmed down.

I asked if he was comfortable with me instilling the first dilation drop, and he agreed. The patient started to get anxious again and we did a grounded breathing exercise together, directing him to feel his body supported by the chair and I would be here to help him if he needed it, reassuring him that this is a safe place and reminding him to focus on his breath. With this exercise, he was able to ride through his anxiety and felt more comfortable doing the second drop. We did the same exercise after administering the second drop and successfully completed the dilated fundus exam.

Using the artificial tear first established that it was not the medication causing the anxiety, but the sensation of the drop hitting his eye. Pairing that with a grounded breathing exercise helped him get through it and the following year we had no issues dilating him. Emergency room physicians and nurses use grounded breathing frequently with their anxious patients and it can be used in the OD office successfully as well.

PTSD. When working with a patient who has PTSD, it’s important to be aware that certain procedures and/or sudden movements can be triggers for symptoms, such as Goldmann tonometry and the bright lights of the BIO. The tonometer coming towards them and the bright lights of the BIO can cause a startle response such as jumping up or shaking, common among those with PTSD. Knowing this ahead of time, make sure to adequately explain what they will experience beforehand, answer any questions about the procedure and let them know you can stop if they need you to, so that the startle response can be minimized or not occur at all. Effective communication between doctor and patient here is critical.

Schizophrenia. A hallmark symptom is visual hallucinations. If you have a patient with a history of schizophrenia, knowing this can help with discerning ocular symptoms from mental symptoms.

As a psychotherapist, I had a patient diagnosed with schizophrenia who reported seeing things regularly in his periphery. Is this an ocular condition or a mental health-related visual hallucination? It could be one or the other, or both, so I referred him to an OD for a dilated fundus exam to have a baseline of retinal health assessed. The patient might be frustrated, angry or feel unheard if their PCP just assumes these symptoms are psychological, which could lead to dire consequences if it is an ocular condition that goes undiagnosed. Be the clinician that listens to them and rules out an ocular etiology to this symptom.

|

|

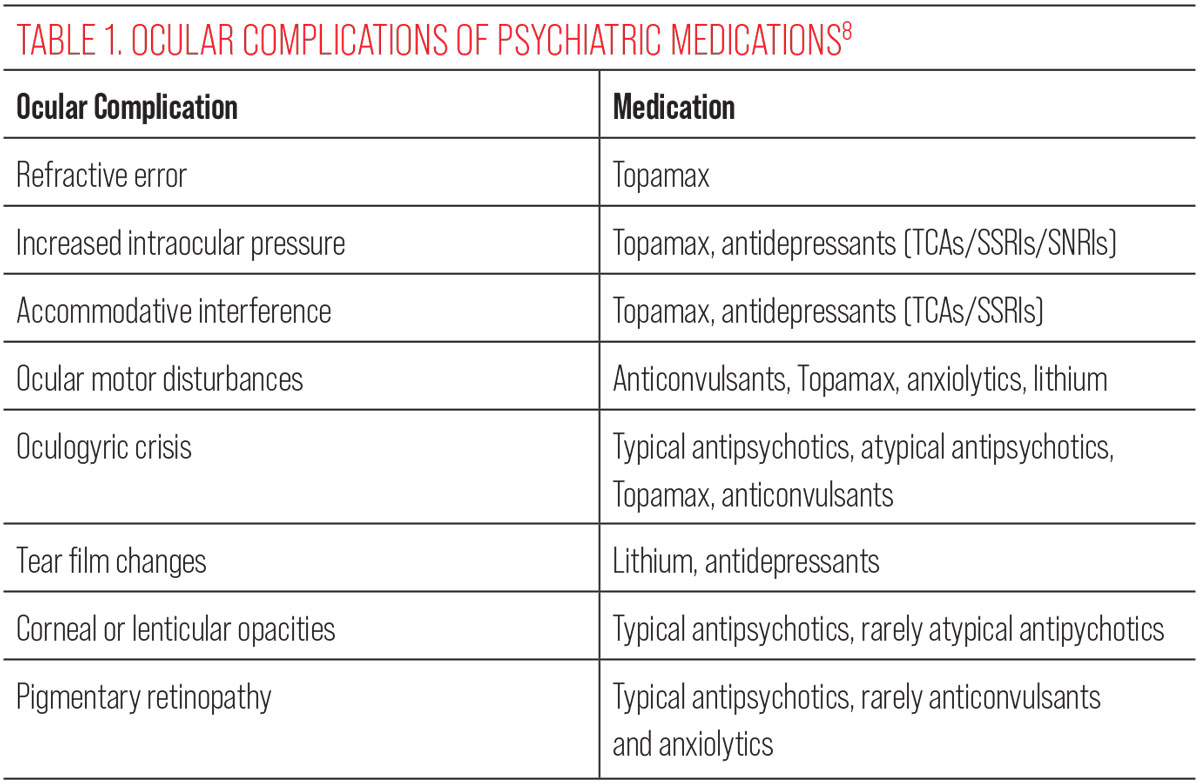

Clinical signs and symptoms of thioridazine toxicity include decreased visual acuity, visual field defects and retinal pigment epithelial disturbances. There is selective uptake of thioridazine in pigmented uveal tissue and the retinal pigment epithelium, which results in toxicity. Photo: Christine W. Sindt, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

|

| Clinical signs and symptoms of thioridazine toxicity include decreased visual acuity, visual field defects and retinal pigment epithelial disturbances. There is selective uptake of thioridazine in pigmented uveal tissue and the retinal pigment epithelium, which results in toxicity. Photo: Christine W. Sindt, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Obsessive-compulsive disorders. Some of your patients will come to you undiagnosed with a mental health condition. An example of this can be trichotillomania, which is an obsessive-compulsive disorder. We may be the first to notice this, especially in the early stages. How do we deal with this during an exam? Don’t jump right into labeling! Ask the patient if they have noticed their eyelashes are missing or if something happened to their eyebrows to explain why they are thinner. Give them an opportunity to explain why they think this is happening and to hopefully explain that they are plucking. Only after that should you discuss what trichotillomania is and refer them to a therapist for treatment.

Self-harm. Evaluate the whole patient, not just their eyes. With rates of depression increasing since the pandemic, incidences of self-harm have also increased. Self-injurious behaviors may include cutting, scratching, burning and bruising. When we greet a patient and during the exam, look for marks on the body that may be suspicious of self-injurious behaviors. Again, we may be the first to notice this, especially if it is new behavior.

Do not confront or embarrass the patient by accusing them of self-injurious behaviors. Communicate carefully that you noticed these marks and ask the patient if they are aware of them and how they may have come about. It could be from numerous things—a fall, accident or abuse, or maybe they will let you know they are self-inflicted. If it is not obvious how they came about, recommend referral to a therapist. If it is abuse, we are mandated reporters, which I discuss next.

Suspected abuse. Optometrists, like other healthcare providers, are mandated reporters. I was fortunate that in my optometric career I only had to report once, but it was very challenging. When we suspect abuse in the exam room, how do we deal with it? Communication with both the patient and parent/caregiver if they are a minor, must be calm, clear and straightforward. It needs to be explained that we are mandated to report suspected abuse, as parents/caregivers often try to stop you from or talk you out of reporting. We do not want to accuse the parents/caregivers, but rather emphasize that we are mandated if we suspect abuse is a possible explanation of what we are concerned about.

The American Optometric Association Standards of Professional Conduct states: optometrists have the responsibility to identify signs of abuse and neglect in children, dependent adults and elders and to report suspected cases to the appropriate agencies, consistent with state law. Mandated reporting laws vary by state, so it is critical for us to know what our reporting responsibilities are in the state we practice in. This information can be found on the websites specific to your state’s department of children and families, elder protective services and disabled persons protection commission.

Handling Argumentative Patients

As previously stated, the COVID-19 pandemic caused an increase in many mental health conditions. Mask mandates in doctor’s offices, vaccinations, boosters, social isolation and fear of getting COVID-19 were and still are just a few of the things that increase anxiety, depression and fear. When people are more anxious, depressed and fearful, it often translates to anger and abrasiveness, and we have become the target of our patient’s misdirected anger and frustration. As ODs, we are not alone in this; PCPs, ophthalmologists, dentists, nurse practitioners and physician assistants are also experiencing similar situations.

How do we deal with this? First, remind yourself to not take it personally. Misdirected means just that; it is not really meant for us, but we get the heat sometimes. Second, we need to defuse the situation. One suggestion is a mindfulness exercise I learned in my training as a therapist, called the Greeting Exercise, which can be very helpful to the OD experiencing more anger from patients.7

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Before greeting each patient, take a few slow breaths to allow for a transition between patients. Visualize the next patient as a human being who may be anxious about seeing you, concerned about what is going on with their eyes or fearful or vulnerable. Say to yourself, this person is coming to me because I have the unique ability to help them with their eyesight and I am grateful for that. Then, greet the patient. It may sound hokey, but give it a try. You’ll most likely find that it can be extremely helpful to take a minute to transition to the next patient and set yourself up to deal with any anger the patient may exhibit. It’s a preventive approach to deal with this trend we are all experiencing as ODs.

Referral Network

All ODs should have a few mental health professionals they can refer patients to. Just like referring patients to PCPs and ophthalmologists, it’s important to have mental health professionals in our community we feel comfortable referring patients to. There is an opportunity for cross-referral if you establish a relationship with mental health professionals in your community. By referring your patients to a therapist, they will thank you by referring additional patients back to you.

Takeaways

Combining effective communication, intent listening, proper screening, grounded breathing exercises and mindfulness will not only help calm the patient, but ensure a more successful visit to your office.

Dr. Pardo has over 20 years of optometric experience in clinical practice, teaching, lecturing and medical affairs. He currently runs a private mental health practice, as well as conducts lectures and workshops on a variety of mental health topics. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. NIMH. Mental Illness. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness. Accessed April 24, 2023. 2. Minhas B. The Mind’s Eye: Ocular Complications of Psychotropic Medications. Rev Optom. January 15, 2016. 3. Kim S, Shin DW, An AR, et al. Mental health of people with retinitis pigmentosa. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90(5):488-93. 4. Moschos MM, Gouliopoulos NS, Kalogeropoulos C, et al. Psychological aspects and depression in patients with symptomatic keratoconus. J Ophthalmol. 2018;7314308. 5. Valtýsdóttir ST, Gudbjörnsson B, Lindqvist U, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. JRheumatol. 2000;27(1):165-9. 6. Mabuchi F, Yoshimura K, Kashiwagi K, et al. High prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(7):552-7. 7. Germer C, Siegel RD, Fulton PR. Mindfulness and psychotherapy, 2nd ed. (Eds.) The Guilford Press. 2013. 8. Richa S, Yazbek JC. Ocular adverse effects of common psychotropic agents. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(6):501-26. |