In 2005, a 64-year-old white female presented to the office as a new patient with complaints of blur at near and distance. She reported that she had not seen an eye care provider in several years. She was taking no medications, other than OTC vitamin supplements.

In 2005, a 64-year-old white female presented to the office as a new patient with complaints of blur at near and distance. She reported that she had not seen an eye care provider in several years. She was taking no medications, other than OTC vitamin supplements.

Diagnostic Data

Refraction yielded 20/20 acuity OD and OS through an increased hyperopic, astigmatic correction. Pupils and extraocular motilities were full. Slit lamp exam of her anterior segments was essentially unremarkable.

Intraocular pressure measured 23mm Hg OD and 22mm Hg OS at 10:00 a.m. Upon dilation, her crystalline lenses showed incipient nuclear sclerosis, though not interfering with vision. Scattered vitreous floaters were visible.

I estimated her cup-to-disc ratios as 0.50 x 0.55 OD and 0.50 x 0.60 OS. The superotemporal neuroretinal rim was somewhat thinned OD and the inferotemporal neuroretinal rim was thinned OS. Her retinal vascular, macular and peripheral retinal examinations were normal. We took stereo-optic disc photos at this visit.

Given her optic nerve appearance and IOPs in the low 20s,

|

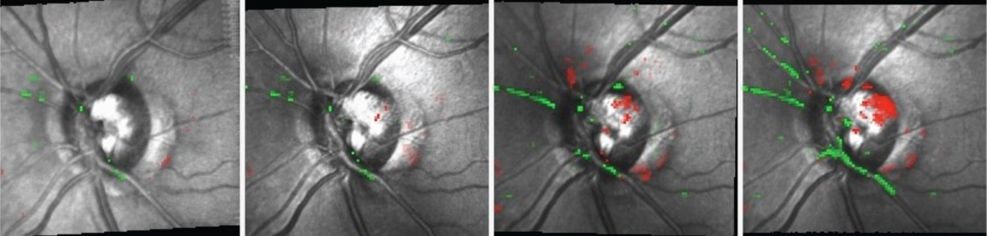

| Over five months, Topographic Change Analysis shows progressive damage to the superotemporal neuroretinal rim OS following a disc

hemorrhage at the same location. |

She returned for follow-up, as scheduled. Pachymetry measured 538μm OD and 535μm OS. Her IOP was 22mm Hg OD and OS at 9:05 a.m. Gonioscopy showed open angles OU to the scleral spur and ciliary body, with minimal trabecular pigmentation. There were no angle abnormalities in either eye. HRT-3 imaging confirmed thinned neuroretinal rims superotemporally OD and inferotemporally OS. Standard white-on-white perimetry showed no glaucomatous field defects OU.

Given the lack of family history for glaucoma, and no other risk factors, the patient appeared to be at risk—albeit low risk—for developing glaucoma.

For the next several years, I followed this patient closely. Ultimately, she developed hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

During this time, her IOP averaged in the low 20s OD and OS, varying from 18mm Hg to 25mm Hg OD and from 16mm Hg to 25mm Hg OS. HRT-3 Topographic Change Analysis confirmed that her nerve fiber layer and neuroretinal rims remained stable in both eyes. Visual fields also remained stable and clear in both eyes.

In 2010, the patient underwent visual field studies on Heidelberg Edge Perimeter (HEP, Heidelberg Engineering), which also confirmed no glaucomatous field loss in either eye. Her optic nerves have remained stable clinically—until recently.

In January 2013, she presented for a scheduled follow-up with a large nerve fiber layer hemorrhage located at 12 o’clock OS. Her IOP was essentially unchanged at that visit, as were HEP field studies.

|

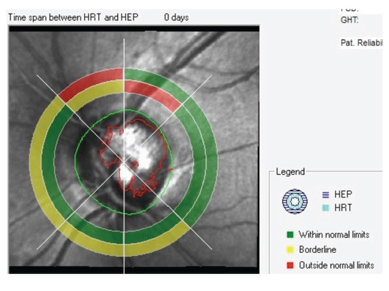

| Structure/function analysis OS indicates damage to the

superotemporal neuroretinal rim, yet the corresponding visual field sector is normal. |

Certainly, the development of a disc hemorrhage in either a glaucoma suspect or a patient with frank glaucoma raises the concern of instability. But, is a disc hemorrhage enough of a clinical finding by itself —with no other discernable changes to the optic nerve or visual fields—to initiate therapy?

While the answer to that question can vary from provider to provider, I think the majority of us would tend not to initiate therapy in this case, especially when all other indices are stable. (Which comes first: disc hemorrhage or optic nerve head progression? Research suggests that structural optic nerve head progression actually presages disc hemorrhage, not the other way around.1)

That said, I also think that the majority of us would watch this patient more closely from this point on. Perhaps more frequent fields and optic nerve imaging are in order, and/or perhaps more frequent office visits. Either way, the development of the disc hemorrhage calls into question the overall stability of the patient’s status.

In situations like these, we should not simply dismiss a hemorrhage as a common event in a patient with glaucoma. Nor should we jump the gun and radically alter the management course. Our plan should be to watch very carefully for any inkling of change to the optic nerve, neuroretinal rim, nerve fiber layer or visual field in each eye.

This is where our newer technology comes in to play. With advances in perimetry and optic nerve imaging, detecting change over time has become easier. Be aware, of course, that not all optic nerve imaging devices consistently yield the same results in the same eye. (See “Don’t Just ‘Treat the Red,’” below.)

For instance, what one instrument calls “normal” may be flagged as “not normal” by a different technology. And, not only are there differences across the industry and across categories of instruments, sometimes even using the same type of instrument over time can give confounding results. That is, the same type of technology (either fields or imaging) may not agree with previous reports of the same eye with the same test.

So, for imaging technologies, image registration becomes incredibly important in assuring that subsequent tests take images in exactly the same location as the baseline image. Some instruments do a better job of this than others.

Management

Management

What does this mean for our patient?

As it turned out, this she eventually did develop demonstrable changes—as measured by tomography, but not by visual fields—to the superotemporal quadrant of her neuroretinal rim OS (where the disc hemorrhage occurred).

Also, from a structure/function perspective, HEP does not yet show functional change at the area of the neuroretinal rim compromise, and OCT still shows the retinal nerve fiber layer adjacent to the compromised neuroretinal rim to be normal. In other words, the only demonstrable change is seen in the neuroretinal rim, not on OCT or on HEP fields.

Given these inconsistencies, what do you do?

Remember, that the development of a disc hemorrhage should cause us to look very critically for any changes in structure or function, or both. So, because at least one method demonstrated structural change over time, I decided to start the patient on therapy, with Zioptan (tafluprost, Merck) HS OS.

Moving forward, we’ll continue to look with a critical level of suspicion for change over time in structure and/or function. Time will tell whether she will be stable enough with this treatment plan.

1. Realini T. Disc hemorrhage and glaucoma progression. Eye World. 2009 Aug; 14(8):60-61.