|

I (Dr. Taub) was interviewing for a job early in my career, and I was asked a question that I occasionally now use in my resident and faculty interviews. The answer I gave was instantaneous and, perhaps in hindsight, a little smug, but ultimately, I got the job. The question from the interviewer was, “If you were stranded on a deserted island and could have one piece of equipment to help you give an eye exam, what would it be?” Of course, you might be thinking of things like a slit lamp, phoropter or retinoscope. Those are all answers I have heard as the questioner. My answer: “Me!” Keep in mind that this was 20 years ago when I was a snot-nosed punk, but even today, I would still give the same answer.

My reasoning was, and remains, that through a good history with proper questioning and sleuthing, almost every condition can be diagnosed without picking up a single piece of equipment. This is not just hubris; according to Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bernard Lown, medical history provides enough information in about 75% of patient encounters to make the diagnosis even before the physical examination and additional testing is completed.1 One study revealed that the initial (upon reading the referral letter and taking the history) and final diagnoses matched in 83% of new patients.2 Another found a success rate of 76%.3 Confidence in the correct diagnosis in this investigation increased from 7.1 on a scale of one to 10 after the patient history to 8.2 after the physical examination and 9.3 after the laboratory testing.3

|

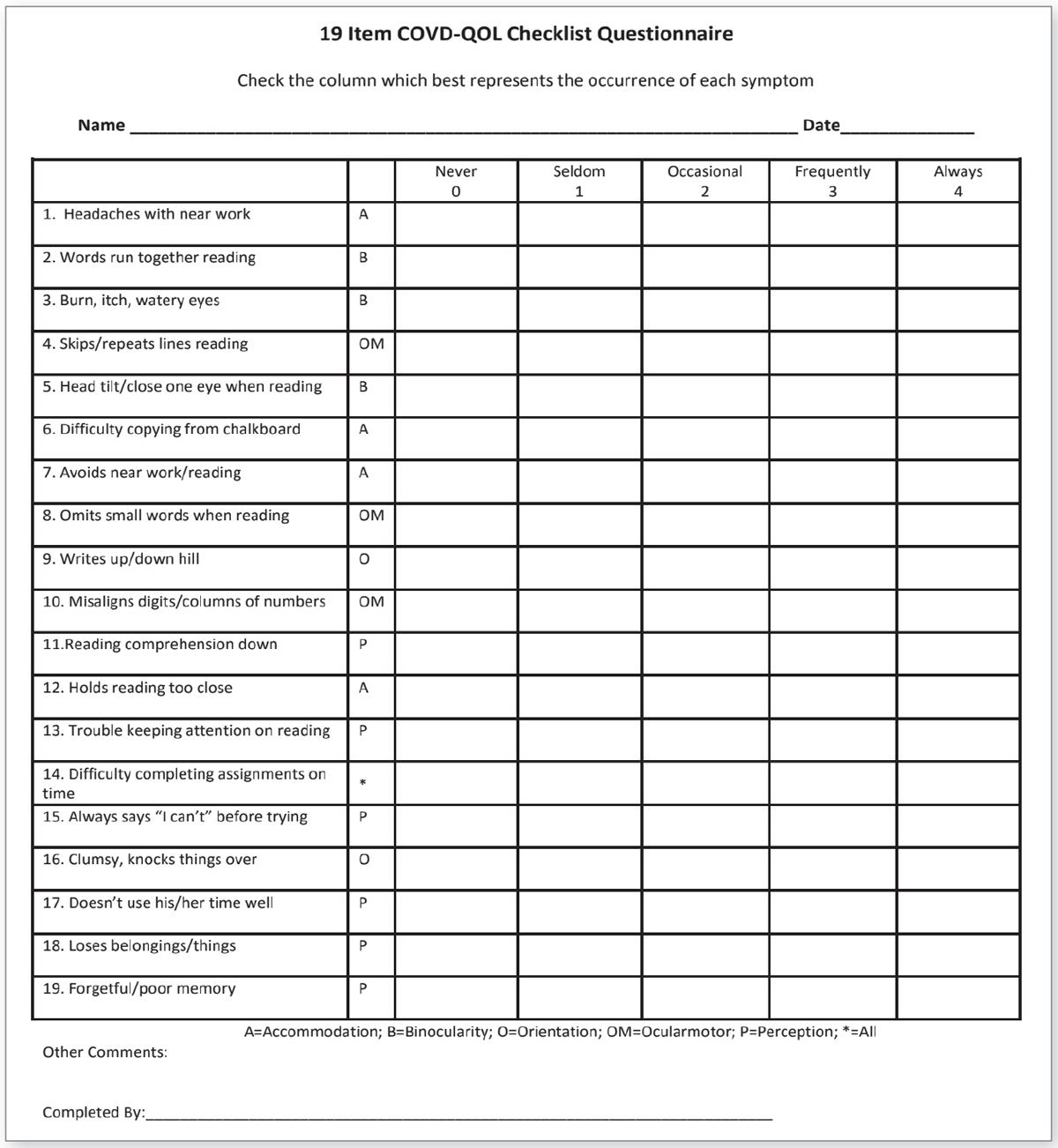

| This checklist focuses on quality-of-life for those suffering from vision impairment. To download a full-sized copy, click here. |

The Trio

History-taking, for most optometrists, starts when the examination begins and hopefully lasts throughout the entire process. However, it can also start before the patient even steps into the room through symptom surveys. These assist by guiding the exam and helping patients make connections between their symptoms and their vision. There are quality-of-life surveys for dry eye, computer vision syndrome and almost every other visual condition in the book. Since this column concentrates on prescribing and binocular vision topics, we will narrow our focus a bit and introduce you to several surveys that you might consider adding to your paperwork when you see a pediatric patient on your schedule.

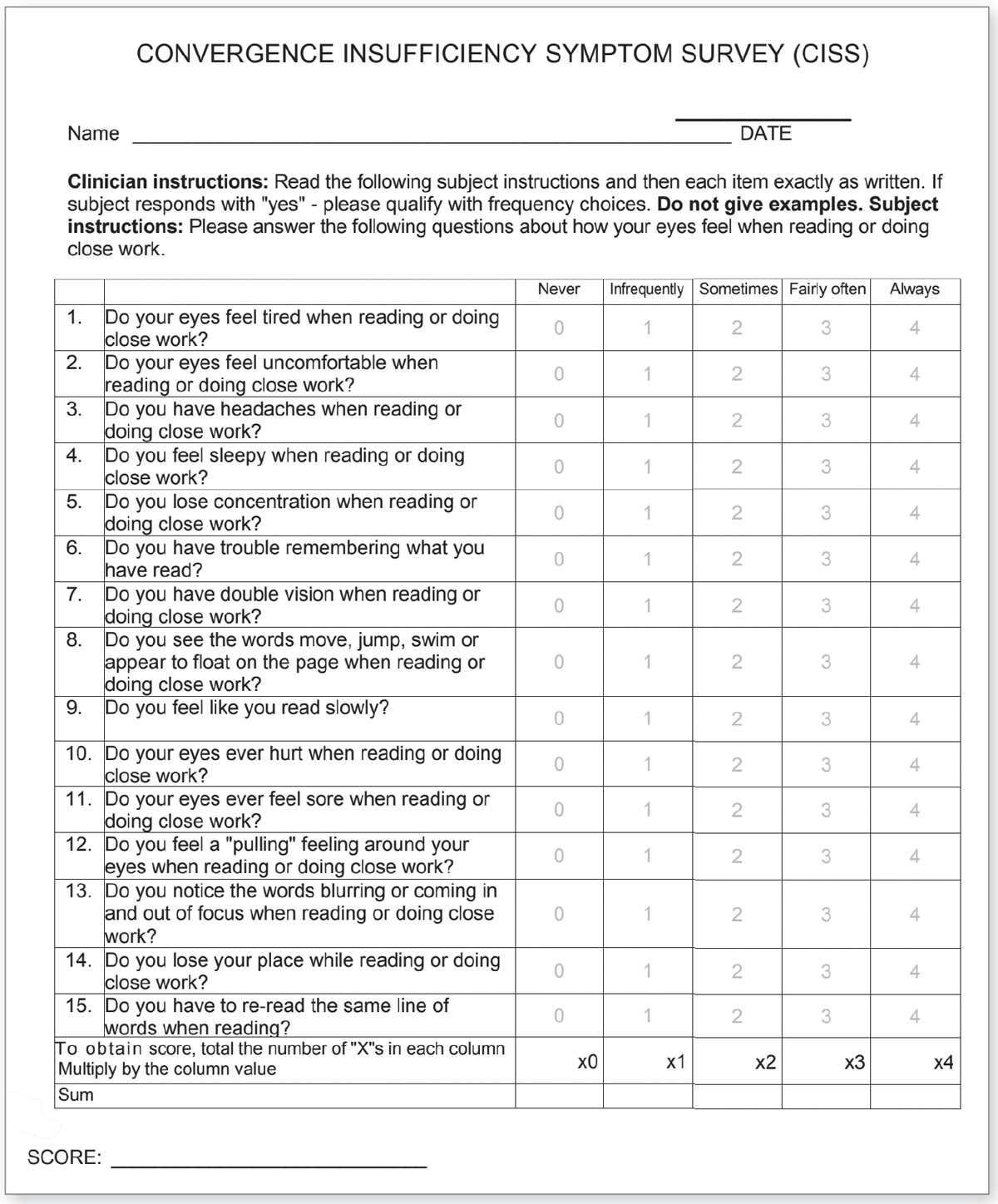

When the landmark Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial found that in-office vision therapy is the superior treatment for convergence insufficiency compared with home therapy and pencil push-ups, the primary measure used to show improvement was the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS).4,5 A 15-question Likert-scale survey, the CISS was designed to quantify the severity of symptoms associated with convergence insufficiency, showing good validity and reliability.6,7

Questions include, “Do you have double vision when reading or doing close work?” and, “Do you have headaches when reading or doing close work?” Each question is rated on a scale of zero to four based on severity, with zero indicating “never” and four indicating “always.” A score of 16 or higher was found to differentiate children with convergence insufficiency from those with normal binocular vision. Even though one study found that children with oculomotor dysfunction, but not those with accommodative insufficiency, had higher CISS scores than those with normal binocular function, the survey remains invaluable in identifying children who suffer from all types of binocular vision issues.8

|

| This form helps pinpoint convergency insufficiency impact. To download, please click here. Click image to enlarge. |

The Quality-of-Life checklist developed by the College of Optometrists in Vision Development (COVD-QOL) was originally a 30-question Likert scale questionnaire but was later shortened to 19 questions. It documents improvement when treating patients with vision therapy, correlates with academic performance and has good test-retest reliability.9-11 We use this checklist as part of all exams that we perform for children older than six. A parent fills it out if the child is younger, but older children can complete it independently. Like the CISS, it uses a zero to four scale, with a four indicating that the symptom “always” occurs. The COVD-QOL overlaps many questions on the CISS but also includes questions relating to forgetfulness, poor memory and saying “I can’t” before even trying a task. A score of 20 or higher indicates the need for a complete binocular vision evaluation.

The largest area of growth that we have seen in our practice involves patients suffering from a brain injury. These injuries can take place shortly before the exam, or they may have happened years to decades earlier. The patient may not realize that their symptoms are linked to the injury, so the Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey (BIVSS) aims to help make that connection and allow the doctor to grade the severity of the visual symptoms. The 28-question, four-point Likert scale survey assesses eight areas of vision, including visual clarity, double vision and photosensitivity. It has been shown to have good validity and test-retest reliability.12,13 A score of 31 is a red flag and an indication that further evaluation must be considered.

Even though the BIVSS was designed for traumatic brain injuries, we use it for all acquired injuries, as well as for patients suffering from neurological conditions like MS and ALS. We also use it to determine potential treatment benefits from vision therapy, tints and occlusion.

Takeaways

There is no one data point on which an entire diagnosis can be based. The same can be said for symptom surveys. They are yet another tool at your disposal to enhance and create a complete patient history that can, in turn, be used to guide your exam and the testing choices that you make, allowing for more effective and efficient diagnosis and treatment.

Since these surveys represent only one data point, there are times when the results match the objective data and times when they do not. If the survey score is high but the objective data is normal or relatively normal, look closely at who filled out the survey. We have seen circumstances in which the parent fills out the survey quite differently than their child does, and vice-versa. As there are three sides to every story, perhaps there are also three sides to every survey. Take the time to consider each to help paint a fuller picture.

If the survey score is low but the objective data indicates a problem, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the survey is wrong; keep in mind that the patient may not be symptomatic yet or ever. The absence of symptoms may in fact be a symptom. The entirety of the examination must be considered altogether in the decision-making process.

The amount of output needed to start using surveys is minimal, but the impact on your clinical exams and patient outcomes can be enormous. Incorporating these tools into your care process in the clinic should be a no-brainer.

Dr. Taub is a professor, chief of the Vision Therapy and Rehabilitation service and co-supervisor of the Vision Therapy and Pediatrics residency at Southern College of Optometry (SCO) in Memphis. He specializes in vision therapy, pediatrics and brain injury. Dr. Schnell is an associate professor at SCO and teaches courses on ocular motility and vision therapy. She works in the pediatric and vision therapy clinics and is co-supervisor of the Vision Therapy and Pediatrics residency. Her clinical interests include infant and toddler eye care, vision therapy, visual development and the treatment and management of special populations. They have no financial interests to disclose.

1. Lown B. The Lost Art of Healing: Practicing Compassion in Medicine. New York: Ballantine Books, 1999. 2. Hampton JR, Harrison MJG, Mitchell JRA, et al. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 1975;2:486-9. 3. Peterson MC, Holbrook JH, Von Hales D, et al. Contributions of the history, physical examination, and laboratory investigation in making medical diagnoses. West J Med. 1992;156:163-5. 4. Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group. The convergence insufficiency treatment trial: Design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(1):24-36. 5. Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(10):1336-49. 6. Borsting EJ, Rouse MW, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in children aged 9 to 18 years. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:832-8. 7. Rouse MW, Borsting EJ, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in adults. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:384-90. 8. Pang Y, Tan QQ, Gabriel H, et al. Application of the convergence insufficiency symptom survey in oculomotor dysfunction and accommodative insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2021;98(8):976-82. 9. Harris P, Gormley L. Changes in scores on the COVD quality of life assessment before & after vision therapy: a multi-office study. J Behav Optom. 2007;18(2):43-7. 10. Vaughn W, Maples WC, Hoenes R. The association between vision quality of life and academics as measured by the college of optometrists in vision development quality of life questionnaire. Optometry. 2006;77(3):116-23. 11. Gerchak D, Maples WC, Hoenes R. Test retest reliability of the COVD-QOL short form on elementary school children. J Behav Optom. 2006;17(3):65-70. 12. Laukkanen H, Scheiman M, Hayes JR. Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey (BIVSS) Questionnaire. Optom Vis Sci. 2017;9(1):43-50. 13. Weimer A, Jensen C, Hannu Laukkanen H, et al. Test-retest reliability of the Brain Injury Vision Symptom Survey. Vis Devel Rehab. 2018;4(4):177-85 |