|

While traveling recently in Italy, I received an email from an acquaintance who lives in Florence. I’ve known him for several years and have been a patron of his shoe store countless times. But we’ve never communicated by email, so I was curious why he was contacting me.

As you can see, it was an urgent issue for him and his family:

I am writing you on behalf of my nephew. He is 22 years old and in his last year of pharmacy school. His doctors recently told him he has problems with his eyes and probably has only a year left of sight. The doctors say he has a lot of pressure behind his eye and they can operate, but it’s a temporary fix. My sister and I are both distraught and we are wondering if you would be able to just take a quick glance at it and see what your opinion is. I am so sorry to bother you but I don’t entirely trust the doctors there. Below are his results from his tests.—Leonardo

Several documents were attached to this email, including a visual field report, optical coherence tomography, retinal nerve fiber layer scans and optic nerve images, along with concise data—including IOPs, medications and follow-up visits—from the nephew about his visits to a local ophthalmologist.

While the circumstances of this particular “social consult” are unique, we’ve all been asked for our opinion on a particular patient’s glaucoma (or corneal, retinal or other) condition. How should we respond? Or, should we decline to respond? Let’s look at this patient’s problem as a case example of how to handle such encounters.

Diagnostic Data

Fortunately, the information from the nephew was substantial.

In February 2015, the patient, a 22-year-old white male, was seen by a local ophthalmologist and diagnosed with glaucoma. Initial IOPs measured 34mm Hg OD and 32mm Hg OS.

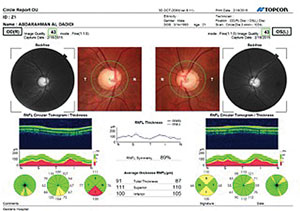

Looking at the optic nerve photos that accompanied the email, I estimated the cup-to-disc ratios to be approximately 0.90 x 0.90 OD and 0.80 x 0.80 OS.

| |

| Clinical data for this patient was limited, but images did show large optic nerves in anatomically large optic cups. |

OCTs of both the right and left retinal nerve fiber layer TSNIT scans showed some flattening of the superotemporal and inferotemporal nerve fiber layers. Macular scans demonstrated some thinning of the ganglion cell complex superiorly in the right eye, but were normal in the left eye. Threshold visual fields demonstrated only a slight enlargement of the blind spot OD and a normal visual field in the left eye.

There was no mention of related medical conditions, if any, or of the remainder of the ophthalmic exam. But I had enough information to see how and why the initial practitioner made the diagnosis of glaucoma.

Management

The patient was initially medicated with Xolamol (dorzolamide 2%/timolol 0.5%, Jamjoom Pharma) BID OU for two weeks. On return visit, IOPs were 20mm Hg OD and 18mm Hg OS. The provider then added Lumigan (bimatoprost, Allergan) HS OU.

On follow-up two weeks later, IOPs were 32mm Hg OD and 30mm Hg OS. The patient was instructed to discontinue Xolamol and Lumigan and was started on Alphagan (brimonidine 0.2%, Allergan) TID OU, Ganfort (bimatoprost 0.03%/timolol 0.5%, Allergan) QD OU, and 500mg acetazolamide PO BID initially, which was reduced to QD after one week.

Two weeks after that visit, the patient’s IOP was 22mm Hg OD and 20mm Hg OS. He was maintained on this dosage until mid-May, at which time his IOPs were “greater than 30mm Hg OU.” At this point, the treating physician discussed surgical options with the patient. Apparently, the discussion centered on the severity of the disease, the inability to adequately maintain acceptable IOP and the suggestion that surgical intervention may offer some temporary relief. But, the provider told the patient the overall visual prognosis was not good and visual impairment was likely to occur in the near future.

Needless to say, such a prognosis was upsetting for this 22-year-old and his family. Ultimately, they reached out to me to provide an independent opinion on the matter.

When looking over the information provided, one thing jumped out at me immediately: both optic discs were anatomically large, with the right larger than the left. Closer examination of the photos showed relatively symmetrical neuroretinal rims, devoid of any notching or damage consistent with advanced glaucoma. In short, the patient had big optic nerves with accompanying big cups. In fact, given the data available, the nerves looked rather normal. So, perhaps the treating physician may have labeled these particular optic nerves as glaucomatous, rather than large physiological nerves?

However, IOP was elevated above 30mm Hg on initial presentation. Even more importantly, post-treatment IOPs were not stable and varied considerably. What was lacking in the initial information provided to me were pachymetry readings. It’s quite possible that the elevated IOPs were simply a result of thick corneas; in the presence of a large cup, maybe this was just a case of an anatomical situation mimicking glaucoma, rather than frank glaucoma.

But even if his central corneas were thick, which would account for the IOP readings above 30mm Hg, that would not explain the variability in the post-treatment IOP readings. With fluctuations as wide as they have been recorded, it made me wonder what the anatomy of the anterior segment looked like—the angle anatomy in particular. While his optic nerves did appear to be normal though large in appearance, it’s possible that the patient may in fact have a mixed mechanism or narrow angle component to his condition.

Ultimately, two important items quickly rose to the surface:

• First, while the actual diagnosis of glaucoma is not firm, the patient does not seem to be in imminent danger of losing vision as his neuroretinal rims appear healthy.

• Second, as in most cases of “social consults,” more information is needed—CCT readings and gonioscopic examination, in this particular case. But, when asked to render an opinion about a patient you’ve never seen, you’ll invariably be handicapped by some lack of information, and what information you do have will be secondhand.

So, what did I tell my shoemaker friend? What was I comfortable saying, and what was I comfortable in declining to say?

Discussion

Given that I know the acquaintance well, I felt I could speak frankly. I reassured him that his nephew did not seem to be in danger of “going blind” in the next few months. This was a major relief to him, his family and the patient, as this was their main concern at this time.

But I did explain to him that some information was missing, so making a firm diagnosis was impossible. I also warned him that his nephew was at risk and needed further evaluation. Although medications used in Europe may differ from those in the United States, that doesn’t sufficiently explain why this patient’s IOPs are so variable, given the broad coverage of medications he is on—a question I could not answer with the information I had.

Here are my suggestions on how to handle the situation when you’re asked to render an opinion on a patient you haven’t seen:

- Remember, any information you are given is secondhand at best and may be incorrect.

- You will probably not be given all the information you need.

- Extenuating circumstances will likely affect what you are comfortable divulging, such as your relationship with the individual asking the question, the patient and the provider rendering the care.

- Try to put a positive spin on the case and be encouraging, although that’s sometimes hard to do.

- Try not to disparage another provider. You can work around a situation when the rendered care appears substandard simply by suggesting that in “difficult cases such as this, a second opinion is always a good thing to consider.”

- If you’re not comfortable with the line of questioning for whatever reason, just tell the other person that it’s not good practice to proffer advice without being able to examine all the facts.

- Lastly, always treat the questioner as you would want to be treated—the “golden rule” of patient care and life.