|

Headache is one of the most common patient symptoms and a frequent condition encountered by optometrists and other health care providers. Millions of Americans are living with the complex, recurrent headache disorder known as migraine.1 The name migraine is derived from the Greek word hemikrania, meaning half of the head, representing one of the most striking features of the condition: In many cases the pain is unilateral.1,2 Migraine often comes with visual signs and symptoms, and patients will present to your office looking for relief. Knowing what to look for is the first step in properly diagnosing migraine and starting patients on the path to better control.

|

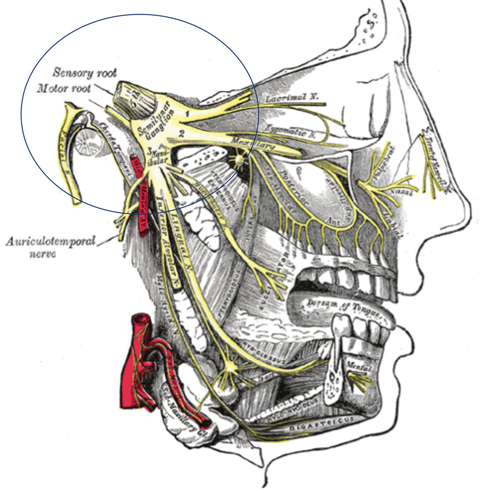

| Fig. 1. The trigeminovascular system may be a prominent component in the circuitry of migraine. Click image to enlarge. Image: Grey’s Anatomy Public Domain |

Headache Basics

The term primary headache describes head pain due to the headache condition itself, and not a result of another cause. A secondary headache is one that is present because of another condition such as sinusitis, for example.

The three types of primary headache are migraine, tension and cluster. Migraine headache is recognized as a distinct neurological disease of complex pathophysiology and is considered the most common disabling brain disorder.1,2

Migraine is further classified into migraine with aura, migraine without aura and chronic migraine.1,2 The typical chief symptom is a severe, unilateral, throbbing head pain or pulsing sensation, which may be preceded or accompanied by visual alterations, difficulty speaking, numbness of the face, nausea, vomiting and extreme sensitivity to light and sound.1-3 About 20% of migraine sufferers experience aura—a complex of neurological symptoms that occurs usually before the headache. Most aura is visual, consisting of a combination of positive visual phenomena (floaters, flashes, zig-zag patterns) and negative phenomena (loss of vision causing blind spots).

Some patients experience a prodrome. One or two days before the attack, they may notice subtle changes, including:

- Constipation

- Mood changes, from depression to euphoria

- Food cravings

- Neck stiffness

- Increased thirst and urination

- Frequent yawning

The Stats

More than 30 million people in the United States experience one or more migraines per year, the majority (75%) of whom are women.1,2 The overall prevalence of migraine is 18% in women and 6% in men.2-4 About 70% of patients have a first-degree relative with a history of migraine, suggesting a genetic component exists.3,4

The Women’s Health Study, which included professional women older than 45, shows that any history of migraine is associated with a higher incidence of major cardiovascular disease.4,5 Those with a history of migraine with aura have the highest cardiovascular risk with a 2.3-fold risk of cardiovascular death and a 1.3-fold risk of coronary vascularization.4,5

Chronic migraine, characterized by the experience of migrainous headache on at least 15 days per month, is highly disabling and may impair a person’s ability to accomplish everyday activities.

Table 1. When It’s Not Migraine: Red Flags1,2

|

The Pathways

Migraine etiology was previously considered a vascular issue resulting from intracranial vasoconstriction followed by rebound vasodilation. However, this contradicts the efficacy of pharmacotherapies that have no effect on blood vessels.2,3,5

More appropriately, studies suggest the origin of a migraine attack is associated with neuronal activation, during which a series of central and peripheral neural and vascular events initiate the migraine.3,4 Proponents describe migraine as primarily a neurogenic process with secondary changes in cerebral perfusion.2,3

A plexus of largely unmyelinated fibers from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve and the upper cervical dorsal roots surround the large cerebral vessels, pial vessels, large venous sinuses and dura mater of the meninges (Figure 1).2,3 When the trigeminal fibers innervating these vessels are activated, a stimulation of nociceptive neurons releases plasma proteins and pain-generating substances such as calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, vasoactive intestinal peptide and neurokinin A.2,3 These substances eventually produce blood vessel dilation, protein extravasation and inflammation. Stimulation of these cranial vessels is quite painful.2-4

Researchers now propose that brainstem activation may be the initiating factor.2,3 Functional brain imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) scans performed during migraine without aura has shown activation of the dorsal midbrain, including the periaqueductal grey and in the dorsal pons, near the locus coeruleus.2,3 Investigators believe the most important receptor in the headache pathway is the serotonin receptor (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]). Immunohistochemical studies have detected 5-HT1D receptors in trigeminal sensory neurons, while 5-HT1B receptors are present on smooth muscle cells found in meningeal vessels.2,3

The Triggers

As there is no known cure for migraine, patients most often rely on avoiding triggers whenever possible.5 For many patients, anything from stress, caffeine, chocolate and alcohol to hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle and foods that contain nitrates, tyramine, monosodium glutamate or aspartame can initiate or aggravate the migraine.1,2 Avoiding such triggers may help to reduce their frequency or severity.5

Table 2. Conditions Associated with Secondary Headache2 | |

| “Thunderclap” Headache | Persistent Worsening Headache |

|

|

Diagnostic Guidelines

The diagnosis of migraine is based on patient history. The International Classification of Headache Disorders diagnostic criteria is as follows:6

1. At least five attacks fulfilling criteria two through four

2. Attacks lasting four to 72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully treated)

3. At least two of the following four characteristics:

a. Unilateral location

b. Pulsating quality

c. Moderate or severe pain

d. Aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity (e.g., walking or climbing stairs)

4. During headache, at least one of the following:

a. Nausea, vomiting or both

b. Photophobia/phonophobia

5. Cannot be attributed to another medical condition

Some signs and symptoms, however, should lead you to suspect a secondary headache such as a “thunderclap” or persistent worsening headache caused by a more serious medical problem (Tables 1 and 2).

It is not uncommon for patients to exhibit characteristics of more than one subtype of migraine, in which case all subtypes that present should be diagnosed. For example, a patient may have frequent attacks with aura but also some attacks without aura.

Stay tuned for our next column, which will discuss the various management strategies you can employ to help these patients overcome the disabling effects of migraine.

| 1. Hildreth CJ, Lynm C, Glass RM. Migraine headache. JAMA. 2009;301(24):2608. 2. Weatherall MW. The diagnosis and treatment of chronic migraine. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 2015;6(3):115-23. 3. Goadsby PJ. Pathophysiology of migraine. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15(Suppl S1):15-22. 4. Van den Maagdenberg AM, Haan J, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD. Migraine: Gene mutations and functional consequences. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:299-305. 5. Estemalik E, Tepper S. Preventive treatment in migraine and the new US guidelines. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:709–20. 6. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. 2013. www.ihs-headache.org/binary_data/1437_ichd-iii-beta-cephalalgia-issue-9-2013.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2017. |