|

In early August this year, a 90-year-old Caucasian male presented for a health examination complaining of acute vision loss in the right eye of four weeks’ duration. He reported he had gotten some hand lotion in both eyes; subsequently, the vision in one of his eyes had remained blurred. He reported that both eyes felt irritated for several days, which eventually cleared, while the blurred vision remained unchanged. He was already a patient of mine; I previously saw him in early 2019, when he was then found to have optic nerve characteristics associated with glaucoma, especially in the right eye. Unfortunately, he did not return that year for follow-up care as scheduled.

Recently, I wrote a column describing a patient who did not comply with my previous plan and proffered some suggestions on how to get the patient to ‘buy into’ your renewed management. This case was a bit different; in this situation, the patient was accompanied by his son, with whom the father was living. His son is a longstanding patient I have been monitoring for several years as a glaucoma suspect. The son reported he had tried coaxing his father to seek care shortly after vision of the right eye was affected, but the father declined until this day.

Case

The father only reported use of guaifenesin (Mucinex) 40mg twice daily and 81mg aspirin once daily, with no other medications taken and no allergies to medications. Entering visual acuities were 20/40 OD and OS with his habitual prescription; best-corrected acuities were 20/40 OD and 20/25-2 OS. Pupils were ERRLA with no afferent pupillary defect noted. Confrontation visual fields OD were slightly constricted superiorly, but there also was mild bilateral dermatochalasis noted.

|

|

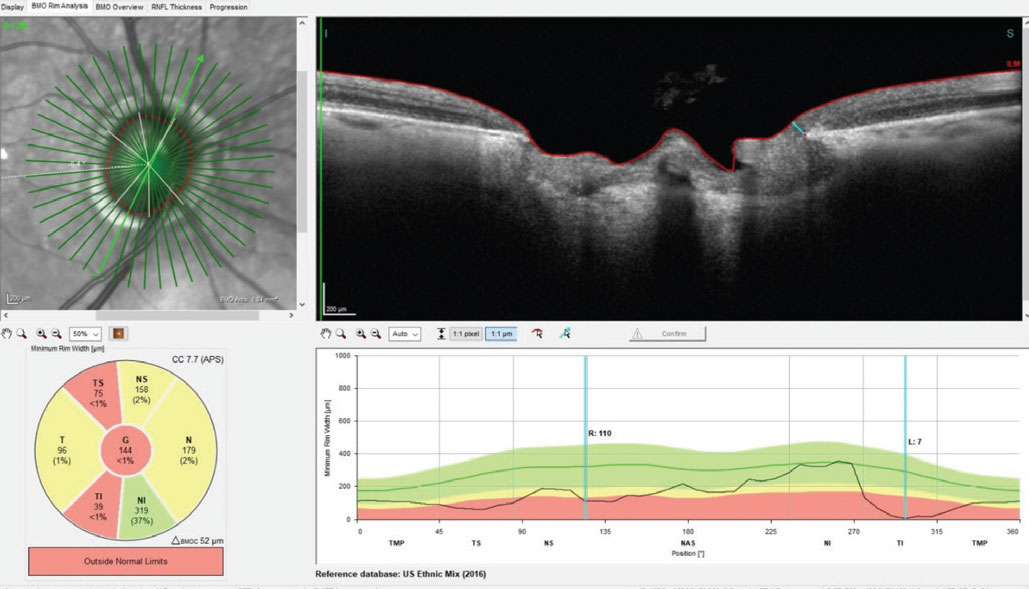

Fig. 1. A Bruch’s membrane opening-minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) scan of the right optic nerve. Note in the section provided, erosion of the inferotemporal neuroretinal rim at the seven o’clock position to a paltry 7µm of remaining axons. Click image to enlarge. |

The slit lamp examinations of the anterior segments were essentially unremarkable, with deep quiet chambers and no corneal abnormalities. Pachymetry readings from his 2019 visit were 634µm OD and 595µm OS. Applanation tensions at the current visit were 26mm Hg OD and 21mm Hg OS. These intraocular pressure readings were 4mm and 3mm Hg higher than in 2019—essentially unchanged.

|

|

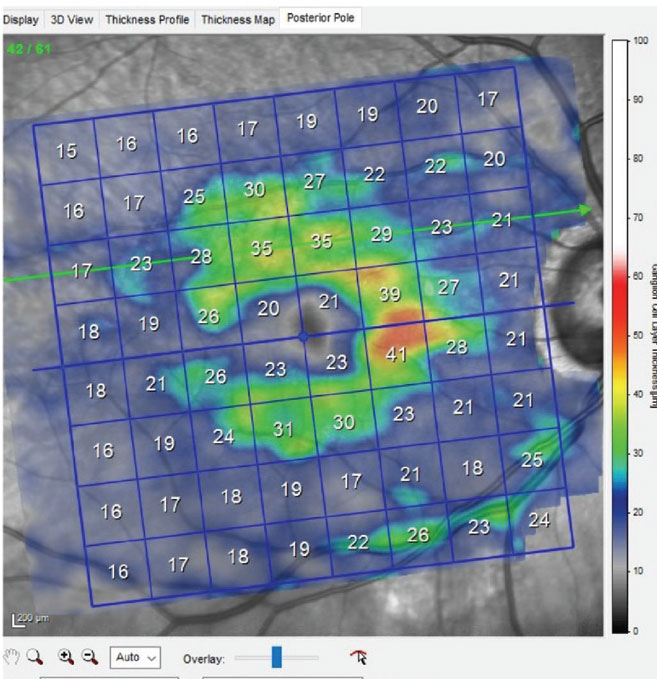

Fig. 2. Ganglion cell layer scan of the patient’s right macula, showing significant loss of ganglion cells in the inferior right portion, which is consistent with inferotemporal neuroretinal rim thinning. Click image to enlarge. |

Through dilated pupils, the patient was pseudophakic OU with clear, centered intraocular lenses and bilateral opened capsules. His cup-to-disc ratio was estimated to be 0.75x0.95 OD and 0.45x0.60 OS. The neuroretinal rim OD was eroded temporally from six o’clock to 11 o’clock with no rim tissue appreciated inferotemporally (Figure 1); that of the OS was thinned, but what remained was mildly pink and decently perfused. The retinal vasculature was characterized by moderate arteriosclerotic retinopathy OU. Both maculae were reasonably healthy, with mild retinal pigment epithelium granulation and scattered drusen, with an epiretinal membrane observed OS (Figure 2). Posterior vitreous detachments existed bilaterally and the peripheral retinal evaluations were normal.

When reviewing the patient’s vision loss history, he recounted first noticing decreased vision when rubbing his eyes after the hand lotion incident and not before. The decrease was more noticeable when rubbing his left eye, a common phenomenon that eyecare practitioners regularly hear. My assumption was the vision loss he noticed had most likely been present for a while due to uncontrolled glaucoma and was only recently noticed upon covering the fellow eye. This reasoning was due to his lack of a pupillary defect, no funduscopic appearance of acute non-glaucomatous optic neuropathy and a previous history of suspected untreated glaucoma. Furthermore, erosion of his right temporal neuroretinal rim was consistent with glaucomatous damage. As such, I was not completely convinced of an acute neuro-ophthalmic cause of unilateral vision loss, though the possibility certainly existed.

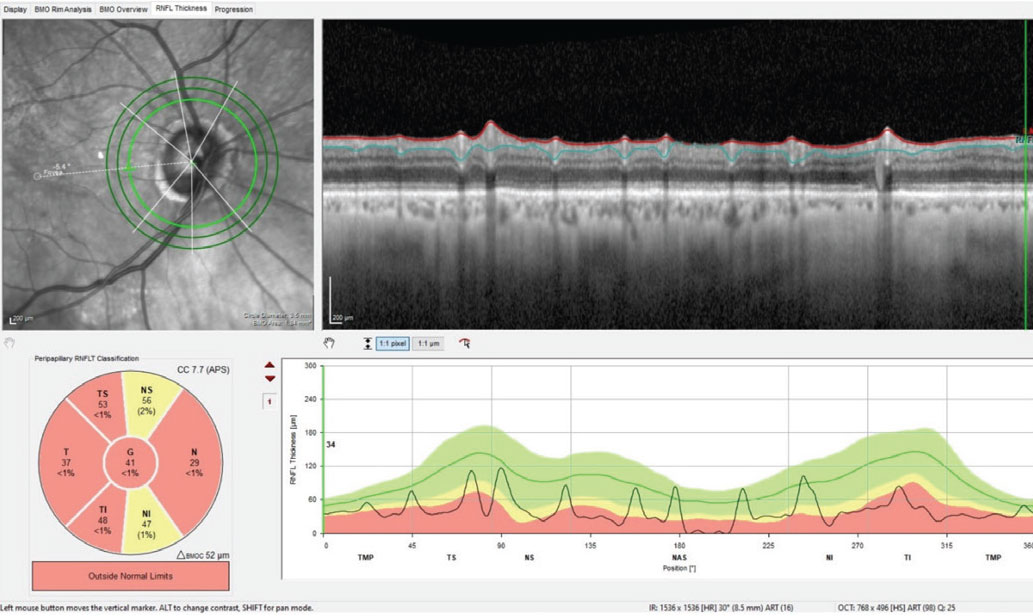

However, upon looking at his previous records and comparing the state of his optic nerves then vs. now, his pachymetry readings and seeing no frank evidence of a neuro-ophthalmic origin, pressure-independent glaucoma moved to the top of the list. This was coupled with the awareness that many cases of normal-pressure glaucoma present with a vascular component to the disease process. The possibility of a concurrent vascular issue is highlighted in the diffuse retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) loss seen in Figure 3.

|

|

Fig. 3. Note the generalized loss of perioptic RNFL tissue in the 3.5mm diameter RNFL circle scan of the right eye; this is consistent with advanced glaucomatous disease. However, taken with the BMO-MRW scan seen in Figure 1, this does call into question the possibility of a concurrent vascular etiology of the observed damage. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

At this point, I enlisted the help of the patient’s son to stress the importance of appropriate follow-up care, given that the son and I had a good doctor-patient relationship and he was a compliant patient himself. While it appeared as though the decreased vision in the right eye was caused by pressure-independent advanced glaucoma, I was not 100% certain that was the only underlying pathology, which in and of itself warranted further investigation. I made my case to the patient and his son; the son made his case to his father, and the father apparently bought into the management plan of a follow-up visit. After a lengthy discussion with the father regarding the need for this follow-up care to assess visual fields for both neuro-ophthalmic field defects and glaucomatous defects, I was able to work the patient into my schedule the following morning.

That next morning, the patient did not show up. Just before his scheduled appointment, the son called and stated that his father simply refused to go to and that he would “live with it.” The son was honest that his father had simply dug in his heels and wanted nothing to do with being seen again.

This unfortunate scenario plays out occasionally in each of our offices. Despite my best efforts back in 2019 and again this August to impart upon the patient the importance of further evaluation to mitigate continued vision loss, some patients simply do not want to nor will follow through. I don’t completely understand that thought process, but it does exist.

Interestingly, a recent study conducted at Duke University looked at the incidence and reasoning for loss to follow-up care of glaucoma patients.1 I was expecting to read that many patients bail out of due to medication noncompliance, but two unrelated findings were fascinating. Establishing the first, the retrospective study was done at a tertiary care facility which receives referred patients from both in- and out-of-state. The researchers found most patients lost to follow-up were actually in-state; individuals closer to the facility were more likely to be lost to follow-up than those further away. I found this interesting but somewhat expected the reverse to true. Of course, there are several reasons why this may be the case, but it was intriguing nonetheless.

The most riveting finding, in my opinion, is that patients with a more advanced disease stage were more likely to be lost to follow-up than patients with milder forms. Again, I would have expected just the opposite. Perhaps patients with more advanced disease feel as if there is no or little hope in management or improvement? I can only conjecture. But as the authors of this study concluded, further investigation as to why this happens is warranted.

So, what do you and I do? How can we help reduce loss to follow-up care for our patients? The simple answer is to do your best. Do your best to offer the highest level of care you can, to stay at the forefront of glaucoma care, to educate your patients as to the importance of disease management and to present material in a way that resonates with them. The simple truth of the matter is that you can lead a horse to water but you cannot make it drink, as the old saying goes. Patients must assume a certain amount of responsibility for their own care.

Dr. Fanelli is in private practice in North Carolina and is the founder and director of the Cape Fear Eye Institute in Wilmington, NC. He is chairman of the EyeSki Optometric Conference and the CE in Italy/Europe Conference. He is an adjunct faculty member of PCO, Western U and UAB School of Optometry. He is on advisory boards for Heidelberg Engineering and Glaukos.

| 1. Williams AM, Schempf T, Liu PJ, Rosdahl JA. Loss to follow up among glaucoma patients at a tertiary eye center over 10 years: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2023;30(4):383-91. |