12thAnnual Pharamaceuticals ReportCheck out the other feature articles in this month's issue: |

The red eye continues to be a common problem in both ophthalmic and primary medical care practices. Although little epidemiological data exists on the red eye presentation, it doesn’t take a comprehensive study to recognize the socioeconomic impact it has on our population. Lost school and work time and the cost of medical visits and prescriptions often exacerbate patient suffering. When the condition presents, optometrists can minimize these red eye burdens with an accurate diagnosis and prompt initiation of treatment, even if it is palliative.

Table 1. Taking a Red Eye History | |

| Symptoms | Itching, burning, tearing, discharge (purulent, mucous, serous), pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, diplopia, blurred vision |

| Onset and Course | Duration, acute vs. chronic, progressive or stationary |

| Location | Unilateral or bilateral |

| Ocular History | Previous episodes, prior exposure to infected people, trauma or chemical injury, contact lens wear, use of topical or over-the-counter drops; current attempted therapies |

| Medical History | Recent upper respiratory infections or illness, atopy, dermatology conditions, thorough review of systems, current medications |

| Social History | Environmental factors (computer use, occupation, hobbies, smoke exposure, sexual history, if applicable) |

Getting Started

As with any office visit, a thorough history is crucial (Table 1). After the history, clinicians should start the localization process with a gross examination outside of the slit lamp with the room lights on. Specifically, take note of the patient’s skin, face, hands and nails. Sometimes the answer can be right in front of us, as in cases of rosacea-related rhinophyma. Most importantly, have the patient look in all positions of gaze. This provides a de-magnified view, which can help you detect intra- or inter-eye asymmetries, in addition to an adequate adnexal observation.

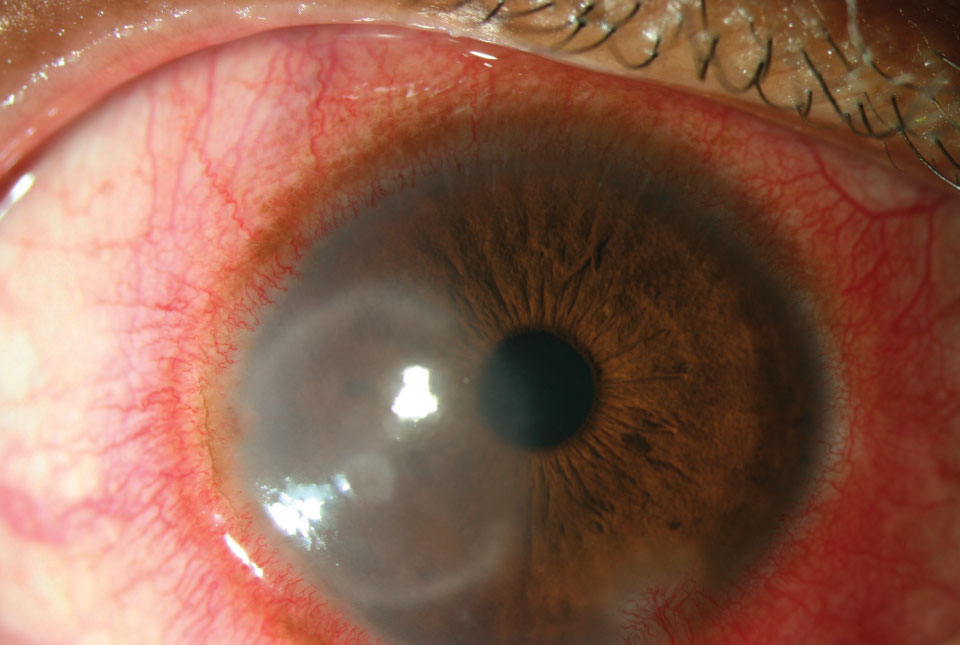

The eye appears red due to blood vessel dilation. Ciliary injection, which results from dilation of anterior ciliary artery branches, implies inflammation of the cornea, iris or ciliary body (Figure 1).1 Conjunctival injection, however, is due to dilation of the more posterior and superficial conjunctival vessels, which causes a more dramatic injection.1 Though not often used, conjunctival grading scales exist to help get an accurate and consistent assessment of bulbar redness both between visits and among group practitioners.2 External photography is another option.

|

| Fig. 1. Intense ciliary flush from pepper spray exposure. Click image to enlarge. |

As always, start the visual exam with an acuity assessment. If needed, use a topical anesthetic with a patient with corneal abrasion or foreign body. The only acceptable deferral would be with acid or alkali injuries, which are a true ocular emergency and prompt irrigation takes precedence over acuity measurement. Pupil and extraocular motility evaluation is key to check for a mid-dilated pupil seen in angle closure or muscle restriction consistent with orbital cellulitis.

During slit-lamp biomicroscopy, gauge the severity of any photophobia. Evert both upper and lower lids and pay particular attention to the lower lid, as sometimes a conjunctival foreign body hides within a fold in the palpebral fissure. For conjunctivitis, identify the type of morphological response: papillary, follicular, membranous/pseudomembranous, cicatrizing or granulomatous.

Next, instill staining agents such as fluorescein, and remember that rose bengal stings more than lissamine green. Always evaluate the other eye in cases of unilateral disease but be careful about cross-contamination in suspected viral cases.

Table 2. Other Possible Red Eye Causes |

|

When measuring intraocular pressure (IOP), disinfect the applanation tonometer properly with 1:10 diluted bleach, as recommended by both tonometer manufacturers and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.3Alcohol wipes with 70% isopropyl alcohol and 3% hydrogen peroxide are not advised. Alternatives to determine IOP include disposable tonometer tips, rebound tonometry and devices with protective covers.

Following a thorough anterior segment evaluation, the decision to dilate varies between practitioners and depends on the exam findings or history. For instance, reduced vision would certainly be a reason to fully evaluate the fundus. Another example would be the report of a high-speed foreign body, which could potentially penetrate the eye.

Clinical acumen determines the next course of action. Following red eye algorithms—plenty of which exist—may be beneficial. While not an all-inclusive list, some common diagnoses include (Table 2):

Viral Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is the most common cause of red eye, and viral is the most encountered variant. Follicles are the classic clinical sign, though they can also be seen in chlamydia and medicamentosa. The adenovirus serotypes are responsible for acute nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis, chronic keratoconjunctivitis, pharyngoconjunctival fever (PCF) and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC). All forms exhibit preauricular lymphadenopathy, so palpate lymph nodes for all suspected cases.

Nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis displays mild signs and symptoms, including conjunctival hyperemia and lid edema. The disease course, which lasts about three weeks, can range from self-limiting to severely visually debilitating. Adequate caution should be stressed to prevent spreading the virus to the patient’s immediate family and coworkers. Chronic conjunctivitis lasts longer, may recur after months of dormancy and usually coincides with an upper respiratory infection. PCF presents with pharyngitis and fever, is highly infectious and is often transmitted through personal contact, swimming pools or fomites.

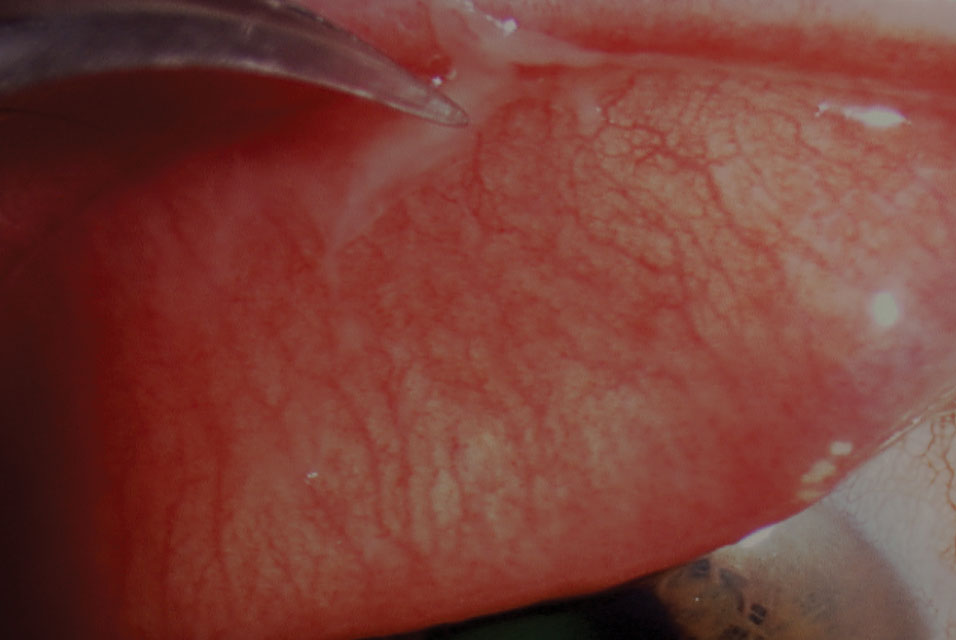

PCF treatment is mostly palliative, unless pseudomembranes are present (Figure 2). Patient education is crucial and should include avoiding shared contact, disinfecting and cleaning any potential viral reservoirs and frequent hand washing. Children and adults should avoid any school or work duties for as long as permissible until the condition resolves due to the propensity of the adenovirus to spread.

Povidone-iodine—traditionally used for disinfection prior to surgery—shows strong promise as a method of controlling adenovirus populations in EKC. One study found povidone-iodine dramatically reduced adenoviral titers compared with 0.1% dexamethasone and artificial tears.4 The treatment also improved discharge, hyperemia, superficial punctate keratitis and pseudomembrane formation. Although povidone-iodine comes in a 5% sterile solution, the researchers found no benefit for concentrations higher than 1% against adenovirus.4

|

| Fig. 2. Forceps removal of a pseudomembrane in viral conjunctivitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Allergic Conjunctivitis

A dramatic increase in allergic disease has occurred in the last few decades, making allergic conjunctivitis a frequently encountered condition.5 This bilateral pathology, which can be seasonal (90% of cases) or perennial, exhibits eyelid edema, conjunctival injection and serous to mild mucous discharge.6 Periorbital venous congestion, known as “allergic shiners,” appears as dark circles in the lower adnexa and results from a pooling of blood secondary to swelling in the sinus cavities. Itching represents the hallmark symptom. Typical associated factors include environmental allergens such as grasses and pollens, outdoor pollution, smoke exposure and contact with animals such as dogs and cats. A history of atopy in the presence of corneal signs of disease and decreased corrected spectacle acuity may warrant a corneal topography to assess for atopic-related keratoconus.

As an initial treatment for allergic conjunctivitis, practitioners may counsel patients to take simple steps such as reducing exposure to an allergen and using cold compresses, artificial tears and eyelid hygiene. Research shows a therapeutic effect on the signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis using cold compresses and artificial tears alone after controlling for pollen exposure.6 Topical ocular agents—alone or in conjunction—are another option. The decision for prescription or over-the-counter medications varies with practitioner and disease severity. An allergy consult may be indicated for patients who fail to respond to treatment.

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

This is the second most common cause of infectious conjunctivitis, with one study estimating an incidence of 135 in 10,000 individuals annually in the United States.7 The true incidence of bacterial conjunctivitis, however, is more difficult to determine, as practitioners treat most cases empirically without culture, and many cases are self-limited and resolve without intervention.

The most common etiologies include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenza.8 Straightforward cases can be treated with a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone. For pediatric cases, Polytrim (Allergan) is an excellent first option because of its additional coverage of H. influenza.

Patients typically present with purulent discharge and bilateral involvement. Further classification is based on severity and presence of membranes, papillae or follicles, as well as culture, if appropriate. Knowing the duration of illness and onset (i.e., acute, hyperacute or chronic) is key when obtaining a history and can quickly narrow the list of differentials.

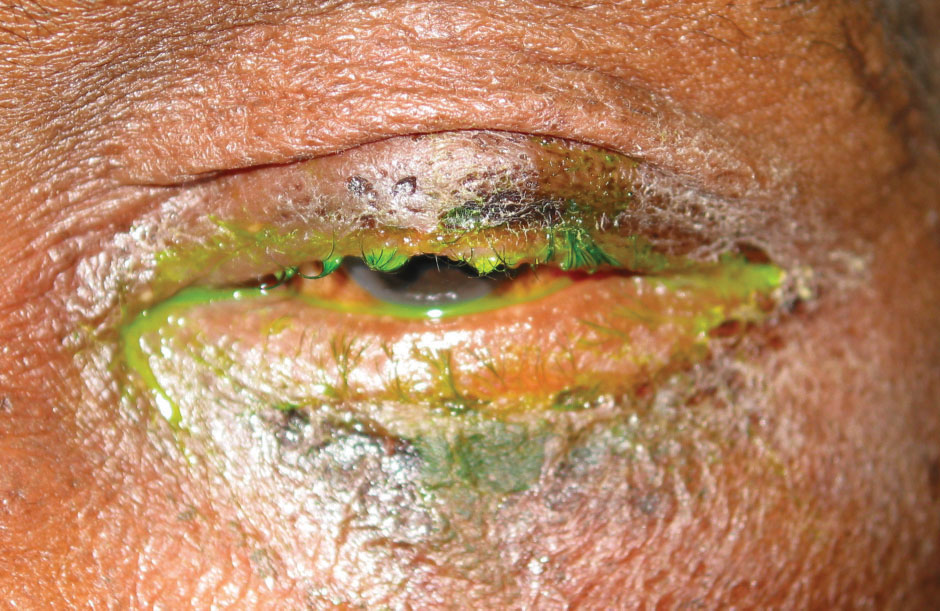

Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis often involves matted, crusted lashes, which provide a large surface area for bacteria to reside (Figure 3). This leads to trichiasis, telangiectasia, hordeola and madarosis. Predictably, this sizable bacterial load can cause inferior corneal staining and accumulation of discharge. S. aureus is the most common cause of chronic cases, followed by Moraxella lacunata, a rod-shaped gram-negative bacterium. In addition to the lids and lashes, the canaliculi and lacrimal sac can act as a reservoir of bacteria for Actinomyces israelii and S. pneumoniae, causing canaliculitis or dacryocystitis, which may present similarly to chronic conjunctivitis.

|

| Fig. 3. Madarosis and purulent discharge in a patient with a bacterial infection. Click image to enlarge. |

Acute bacterial conjunctivitis has a rapid onset with mucopurulent discharge, inflamed bulbar conjunctiva and papillae. Symptoms typically resolve within 14 days. Swollen lids, chemosis and excessive mucopurulent discharge indicate the rarer hyperacute form. Hyperacute cases may also present with pseudomembranes and tender preauricular nodes. Due to its strong association with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis, culture may be warranted in severe presentation. Explore the history for any sexually transmitted disease (STD) and consider blood work if the presentation rapidly progresses despite treatment.

Chlamydia is the most common reportable STD in the United States and has an incidence of 2.9 million individuals.9 Infection is caused by C. trachomatis, C. pneumoniae and C. psittaci. C. trachomatis, the causative organism for trachoma, produces a follicular response of both the upper palpebral and limbal bulbar conjunctiva. Eventual scarring of the latter area leads to Herbert’s pits. Though rare in the United States, it poses a substantial risk in other countries with limited access to healthcare and hygiene.10 However, adult inclusion conjunctivitis caused by C. trachomatis serotypes D-K is fairly common in the United States. This presentation is characterized by follicles of the palpebral conjunctiva—more so in the lower fornix—and discharge. Treatment options include 100mg of oral doxycycline twice daily or a single azithromycin dose of 1,000mg.11

A new broad spectrum antiseptic—povidone-iodine 0.6% with dexamethasone 0.1%—under investigation for both adenoviral and bacterial conjunctivitis is showing promise. In a Phase II trial, QID dosing showed a statistically significant improvement in rates of clinical cure and viral eradication compared with vehicle by day six.12

Dry Eye

Patients who complain of dry eye often also present with red eyes. But just because a patient complains of dryness doesn’t automatically mean a diagnosis of dry eye. Practitioners must initiate a full dry eye workup that includes a validated dry eye questionnaire and tear break-up time, in addition to meibography (photography) or meiboscopy (transillumination) and expression to determine the meibomian gland status. An incomplete workup could lead to inappropriate and ineffective treatment (e.g., prescribing doxycycline in a patient with significant gland loss).

An Illuminating New Therapy for RednessPatients often seek over-the-counter solutions for their red eye. However, the use of topical vasoconstrictors such as tetrahydrozoline and naphazoline only provide temporary relief from hyperemia. They often encourage excessive use due to their rapid tachphylaxis. The release of Lumify (brimonidine tartrate 0.025%, Bausch + Lomb) onto the market provides a safe and effective over-the-counter topical medication for hyperemia with much less risk of rebound hyperemia and tachyphylaxis due to its alpha-2 selective mechanism of action.1 Lower ocular redness scores at one minute suggest a quick onset of action.1 Dosage is one drop in the affected eye every six to eight hours, not to exceed four times daily.

|

The debridement-scaling technique is useful to remove accumulated tissue and debris from the line of Marx (LOM) and keratinized lid margin.13 To accomplish this, use a lateral motion with the golf club spud along the LOM to remove the lissamine green stained cells.

Clinicians must counsel patients about the chronic nature of dry eye disease. Exacerbations occur even with patients who are usually well controlled. Clinicians should recommend a specific artificial tear or lid scrub product to ensure the patient uses the best therapy for their specific dry eye condition (e.g., lipid-based, preservative-free). Other therapies include topical anti-inflammatories, fish oil, tetracyclines and moisture goggles, to name a few.

Episcleritis

This condition is usually diffuse or simple with benign, mild inflammation that resolves within days to weeks.14 It is frequently located between the palpebral fissures.15 Patients complain of mild discomfort or irritation and may present with epiphora. Because epislceritis involves the conjunctival and superficial episcleral plexi, the affected area appears bright red. This is in contrast to the deep episcleral plexus involvement with scleritis and the characteristic bluish-violet hue.16 Additionally, IOP may be elevated due to increased episcleral venous pressure.17

Episcleritis is usually a self-limiting condition with nearly a 20% resolution rate without treatment, and patient education or topical lubricants may suffice.14 Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs provide no benefit over artificial tears.18 Clinicians may elect to treat with a mild topical steroid.

A widely-used technique to differentiate episcleritis from scleritis is using phenylephrine to blanch congested conjunctival and superficial episcleral blood vessels. Some advocate using the 2.5% concentration, while others prefer 10%.14,19 The deep episcleral plexus affected in scleritis should not blanch.

Rosacea

Ocular rosacea occurs in 6% to 50% of patients with cutaneous rosacea.20 Because cutaneous rosacea usually affects the face, simply looking at the patient can lead to its differential. Signs or symptoms include burning or stinging, telangiectaic lid margins, conjunctival injection, photophobia and blurred vision. It only takes one or more of these to diagnose ocular rosacea, according to the National Rosacea Expert Committee.20

About 20% of rosacea patients develop ocular manifestations first.20 Contradicting early studies, reports of ocular rosacea in young children have dramatically increased over the past decade.21 Making the diagnosis in this demographic has its challenges, given both the low suspicion for ocular rosacea and that facial manifestations usually present in patients older than 30 years of age.21 If identified, tetracycline should be avoided.

Demodex infestation—both D. folliculorum and D. brevis—is more common in rosacea patients, though the mite’s role in the condition remains unclear. This should be considered in cases refractory to typical ocular rosacea treatment.22 Patients are often instructed to use lid scrubs for ocular rosacea, and some advocate 50% tea tree oil scrubs to address the Demodex concern.23

Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

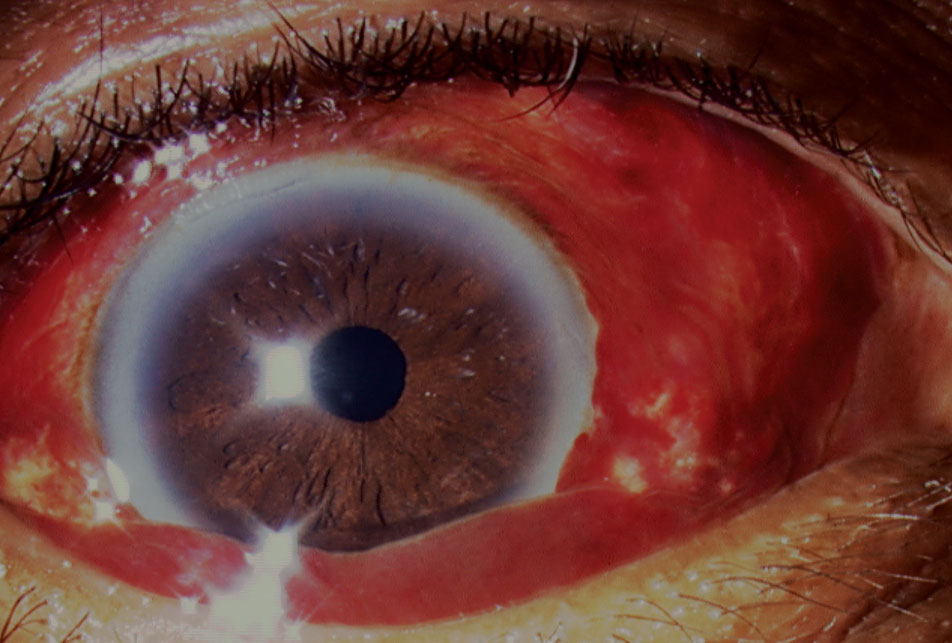

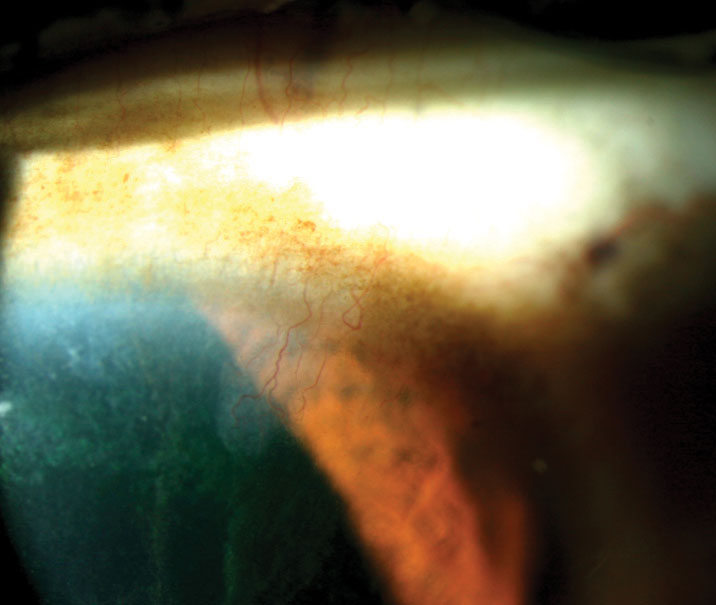

This pooling of blood under the conjunctiva, typically in the inferior and temporal areas, usually does not require treatment and clears within a few weeks (Figure 4).24,25 Etiologies for subconjunctival hemorrhage (SCH) include trauma (e.g., contact lens-induced in younger patients, eye rubbing, blunt injury), infections (e.g., acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis), anticoagulation,

|

| Fig. 4. Ocular lubricants were required in this case due to the bullous nature of the subconjunctival hemorrhage, which caused corneal damage. Click image to enlarge. |

Valsalva maneuvers and systemic disease (e.g., hypertension, bleeding disorders).25 SCHs may result from vascular tumors such as Kaposi’s sarcoma, and cavernous hemangiomas may cause recurrent bouts in early adulthood.24 Reports of SCHs associated with carotid cavernous fistulas exist.26 Unexplained bilateral SCHs in a pediatric patient should flag the clinician to consider nonaccidental or accidental traumatic asphyxia, or Perthes syndrome.27 Here, violent compression of the thorax leads to a sharp increase in venous pressure around the superior vena cava.

Contact Lens Wear

Newer materials and wear schedules have reduced the incidence of this, but contact lens use, especially in cases of excessive wear, can predispose patients to a host of red eye issues. Over-wear leads to a greater susceptibility to bacterial conjunctivitis as bacteria may accumulate in microcystic areas created by the hypoxic cornea. First-line therapy for contact lens-related red eye should be discontinuation of lens wear unless the issue was caused by a poor fit or an insertion problem.

Conjunctival hyperemia occurs in both new and established wearers. Injection is typically diffuse, circumlimbal and can have multiple etiologies, including improper fit, poor lens maintenance, non-adherence to disposal regimen and adverse reaction to a lens solution. This may lead to more severe complications such as superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, which presents with marked injection of the superior limbus. Contact lens-induced acute red eye—an acute inflammation characterized by sudden pain and photophobia—results from overnight wear and is more likely to occur with H. influenzae colonization.28 Clinicians should rule out early microbial keratitis by scanning carefully for infiltrates. Pain and photophobia frequently accompany this finding. Contact lens-induced peripheral ulceration may also present with infiltration but usually has milder symptoms.29

Corneal Complications

When examining the red eye patient, the entire limbus and cornea should be evaluated to determine the extent of the injection as well as to rule out any corneal lesions that may be obscured by the lids in primary gaze (i.e., phlyctenules, infiltrates). Corneal involvement is possible in many types of conjunctivitis, with some exception to allergic conjunctivitis, and is more likely in chronic and aggressive cases. Herpes simplex keratitis can manifest in several different ways, including vesicles, dendritic ulceration, stromal keratitis and endotheliitis. An ulcerative presentation may appear daunting, but many of the same methods of a red eye examination still apply. Determining whether the ulcer is infectious guides treatment and management. Infectious ulcers tend to be larger and central, with symptoms of pain and photophobia and signs of anterior chamber reaction.

Examination of a mechanical injury, whether from an abrasion or a foreign body, should start with a pointed history to determine the nature of the incident. Similar to anterior uveitis, signs include pain, epiphora, photophobia and ciliary flush. Vital tests include lid eversion and instillation of fluorescein dye to assess the cornea and track marks. Treatment of a corneal abrasion typically involves prophylactic topical antibiotics, patching and cycloplegia until the cornea re-epithelializes. Interestingly, a study in Nepal found that 96% patients with a corneal abrasion healed without infection.30

|

| Fig. 5. Note the classic “icicle” staining pattern extending toward the pupil in this patient with limbal stem cell deficiency. Click image to enlarge. |

Uveitis

This should always be among the top differentials in a patient presenting with acute conjunctival hyperemia. Injection is characteristically circumlimbal and engorged variably with cells and flare in the anterior chamber. Corneal findings, including keratic precipitates, typically occur in the lower half of the cornea. Suspected cases warrant a dilated exam to assess the vitreous and retina for signs or lesions suggestive of intermediate and posterior involvement.

Grading of cells and flare is important to maintain consistency, especially in practices with multiple practitioners. In these settings, consider using grading scales from the standardization of uveitis nomenclature group, which used a 1mm x 1mm slit beam to stage the number of cells and level of flare.31 Topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of anterior uveitis treatment. The instillation interval depends on disease severity, and aggressive early therapy is common practice.

Practice Pearls

For unresolved or recurrent cases, reconsider the working diagnosis. The dilated exam can help to rule out posterior disease. Revisit the review of systems to spot any missed items or symptoms. Additional diagnostic tests such as cultures for purulent discharge, biopsies for suspected neoplasm and blood tests for sarcoidosis, thyroid or autoimmune conditions may be helpful.

Dr. Vo is an assistant professor at Western University in Pomona, California

Dr. Williamson is the residency supervisor at the Memphis VA Medical Center.

|

1. Bhatia K, Sharma R. Eye Emergencies. In: Adams J, ed. Emergency Medicine Clinical Essentials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2013:209-26. 2. Macchi I, Bunya VY, Massaro-Giordano M, et al. A new scale for the assessment of conjunctival bulbar redness. Ocul Surf. 2018;16(4):436-40. 3. Junk AK, Chen PP, Lin SC, et al. Disinfection of tonometers: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(12):1867-75. 4. Kovalyuk N, Kaiserman I, Mimouni M, et al. Treatment of adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis with a combination of povidone-iodine 1.0% and dexamethasone 0.1% drops: A clinical prospective controlled randomized study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(8):e686-e692. 5. Mantelli F, Lambiase A, Bonini S. Clinical trials in allergic conjunctivits: A systematic review. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;66(7):919-24. 6. Bilkhu PS, Wolffsohn JS, Naroo SA, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacologic treatments for acute seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):72-8. 7. Smith AF, Waycaster C. Estimate of the direct and indirect annual cost of bacterial conjunctivitis in the United States. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009;9(1):1-11. 8. Cavuoto K, Zutshi D, Karp CL, et al. Update on bacterial conjunctivitis in South Florida. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):51-6. 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The state of STDs in 2017. www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/infographic.htm. Accessed January 27, 2019. 10. Allen SK, Semba RD. The trachoma menace in the United States, 1897-1960. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(5):500-9. 11. Georgalas I, Rallis K, Andrianopoulos K, et al. Evaluation of single-dose azithromycin versus standard azithromycin/doxycycline treatment and clinical assessment of regression course in patients with adult inclusion conjunctivitis. Curr Eye Res. 2013;38(12):1198-1206. 12. Shire initiates phase 3 clinical trial program for shp640 in infectious conjunctivitis for adults and children. Eyewire. eyewire.news/articles/shire-initiates-phase-3-clinical-trial-program-for-shp640-in-infectious-conjunctivitis-for-adults-and-children. Accessed February 25, 2019. 13. Korb DR, Blackie C. Debridement-scaling: a new procedure that increases meibomian gland function and reduces dry eye symptoms. Cornea. 2013;32(12):1554-7. 14. Daniel Diaz J, Sobol EK, Gritz DC. Treatment and management of scleral disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61:702-17. 15. Bowling B. Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2015. 16. Okhravi N, Odufuwa B, McCluskey P, Lightman S. Scleritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(4):351-63. 17. Pikkel J, Chassid O, Srour W, et al. Is episcleritis associated to glaucoma? J Glaucoma. 2015;24(9):669-71. 18. Williams CPR, Browning AC, Sleep TJ, et al. A randomised, double-blind trial of topical ketorolac vs artificial tears for the treatment of episcleritis. Eye (Lond). 2005;19(7):739-42. 19. Sims J. Scleritis: Presentations, disease associations and management. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88(1046):713-18. 20. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: Part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(5):749-58. 21. Suzuki T, Teramukai S, Kinoshita S. Meibomian glands and ocular surface inflammation. Ocul Surf. 2015;13(2):133-49. 22. Brown M, Hernández-Martín A, Clement A, et al. Severe Demodex folliculorum-associated oculocutaneous rosacea in a girl successfully treated with ivermectin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(1):61-63. 23. Wladis EJ, Adam AP. Treatment of ocular rosacea. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63(3):340-46. 24. Tarlan B, Kiratli H. Subconjunctival hemorrhage: Risk factors and potential indicators. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1163-70. 25. Wu AY, Kugathasan K, Harvey JT. Idiopathic recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhage. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47(5):28-9. 26. Pong JCF, Lam DKT, Lai JSM. Spontaneous subconjunctival haemorrhage secondary to carotid-cavernous fistula. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 36(1):90-91. 27. Spitzer SG, Luorno J, Noel LP. Isolated subconjunctival hemorrhages in nonaccidental trauma. J AAPOS. 9(1):53-56. 28. Sankaridurg PR, Vuppala N, Sreedharan A, Vadlamudi J, Rao GN. Gram negative bacteria and contact lens induced acute red eye. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1996;44(1):29-32. 29. Alipour F, Khaheshi S, Soleimanzadeh M, Heidarzadeh S, Heydarzadeh S. Contact lens-related complications: A review. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12(2):193-204. 30. Upadhyay MP, Karmacharya PC, Koirala S, et al. The Bhaktapur eye study: Ocular trauma and antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(4):388-92. 31. Jabs DA. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):509-16. |