Conjunctivitis is a common infection in primary optometric care. Often, children experience more severe side effects associated with conjunctivitis than adults, such as preseptal cellulitis and even orbital cellulitis/osteomyelitis.1,2

Conjunctivitis is a common infection in primary optometric care. Often, children experience more severe side effects associated with conjunctivitis than adults, such as preseptal cellulitis and even orbital cellulitis/osteomyelitis.1,2

Indeed, statistics show that acute conjunctivitis is the most common eye disorder in young children.3,4 Here, we examine research pertinent to the diagnosis and management of conjunctivitis in children and review new insights, key therapies and specific guidelines for more effective treatment strategies.

Typical Pathogens in Children

Adult conjunctivitis is often caused by gram-positive organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis.5 In children, however, conjunctivitis is caused by the nontypeable forms of Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis and adenovirus.5,6

Many clinicians thought that fewer cases of Haemophilus influenzae conjunctivitis would surface following the advent of a Haemophilus flu vaccine in 1985. However, this has not been the case because the Haemophilus flu bacteria that cause conjunctivitis are the nontypeable form, which are not accounted for by the vaccine.7

Diagnosing Bacterial Conjunctivitis

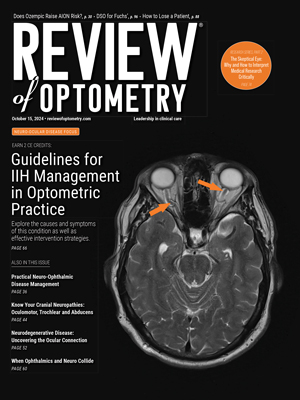

This child presented with conjunctivitis.

Culturing is not typical in cases of acute conjunctivitis because most infections are self-limiting. Also, most clinicians treat the patient based on in-office findings regardless of culture results. So, clinical findings are often critical and can help indicate potentially serious bacteria.

You must first rule out trauma in any child who presents with a red eye because it can alter the management plan and increase the risk for gram-positive infection, such as MRSA or Streptococcal cellulitis.8 Once trauma is ruled out, differentiate bacterial conjunctivitis from allergic or viral conjunctivitis by looking for the presence of a mucopurulent discharge and concurrent adenopathy as well as by examining the degree of redness and overall presentation.

As previously noted, preseptal cellulitis is one of the most common complications associated with acute bacterial conjunctivitis. When considering preseptal cellulitis, examine the skin and adnexa around the orbit for a discrete reddish sheen. Patients with a preseptal cellulitis typically have ethmoidal or maxillary sinus involvement, which results in orbital tenderness.9

One of the more common causes of preseptal cellulitis is Pneumococcus. So, depending upon disease severity, white blood cell count and the presence of fever, high-dose Augmentin (amoxicillin clavulanate, GlaxoSmithKline) or an intramuscular injection of Rocephin (ceftriaxone, Roche) should be dispensed by a pediatrician or a pediatric ophthalmologist.10

When to Refer to a Pediatrician

Some, but not all, patients should be referred to a pediatrician. In general, a timely referral is essential when children with conjunctivitis present with severe complications, such as cellulitis. Additional findings that often require referral to a pediatrician include:3,11

• Fever or general malaise.

• Acute earache or ear infection. (Approximately one-third of all childhood cases of conjunctivitis present concurrently with ear ache.)

• A notable red sheen around the eyelids.

• Noted purulent rhinorrhea or an upper respiratory infection associated with any fussiness or sleeplessness.

Treatment

Treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis in all neonates as well as in children who present with earaches, systemic involvement, or preseptal cellulitis and/or cellulitis should be facilitated by a pediatrician. Infants with bacterial conjunctivitis are typically treated with Polytrim (polymyxin B sulfate and trimethoprim, Allergan). In children older than two years, treatment may be initiated with Polytrim, AzaSite (azithromycin, Inspire) and/or topical fluroquinolones, such as Besivance (besifloxacin, Bausch + Lomb). In a recent study, Besivance showed significant bactericidal activity against many common pathogens associated with both childhood and adult forms of conjunctivitis, including MRSA.12 Because t.i.d. dosing of Besivance is permissible every four to 12 hours, children can be dosed in the morning, when they return home from school/daycare, and before bed. So, this particular regimen fosters improved compliance and effectively eliminates potential issues associated with the use of medications at school.

The treatment of children with conjunctivitis is quite different than the treatment of adults. Generally, children exhibit respiratory pathogens, such as H. influenzae or S. pneumoniae. You must also be vigilant for secondary key findings, such as redness around the orbital area, earache/ear infection, mucopurulent rhinorrhea or the presence of a fever. Prompt referral to a pediatrician for any of these key findings helps facilitate successful management.

Dr. Karpecki is a paid consultant for Inspire Pharmaceuticals and Bausch + Lomb. Neither he nor Dr. Shechtman have any direct financial interest in the products mentioned. They thank Stan L. Block, M.D., F.A.A.P., professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine and the University of Louisville Medical School, for contributing to this article.

1. Donahue SP, Khoury JM, Kowalski RP. Common ocular infections. A prescriber’s guide. Drugs. 1996 Oct;52(4):526-40.

2. Pomeranz HD, Storch GA, Lueder GT. Pediatric meningococcal conjunctivitis. J Pediatric Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1999 May-Jun;36(3):161-3.

3. Buznach N, Dagan R, Greenberg D. Clinical and bacterial characteristics of acute bacterial conjunctivitis in children in the antibiotic resistance era. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005 Sep;24(9):823-8.

4. Buck JM, Lexau C, Shapiro M, et al. A community outbreak of conjunctivitis caused by nontypeable Streptococcus pneumoniae in Minnesota. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Oct;25(10):906-11.

5. Cavuoto K, Zutshi D, Karp CL, et al. Update on bacterial conjunctivitis in south Florida. Ophthalmology. 2008 Jan;115(1):51-6.

6. Wald ER. Conjunctivitis in infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997 Feb;16(2 Suppl):S17-20.

7. Klein JO. Role of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in pediatric respiratory tract infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997 Feb;16(2 Suppl):S5-8.

8. Babar TF, Aaman M, Kahan MN, et al. Risk factors of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009 Jan;19(1):39-42.

9. Herz G, Gfeller J. Sinusitis in pediatrics. Chemotherapy. 1977;23(1):50-7.

10. Donahue SP, Schwartz G. Preseptal and orbital cellulitis in childhood. A changing microbiologic spectrum. Ophthalmology. 1998 Oct;105(10):1902-5.

11. Bingen E, Cohen R, Jourenkova N, et al. Epidemiologic study of conjunctivitis-otitis syndrome. Pediatr Infec Dis J. 2005 Aug;24(8):731-2.

12. Karpecki P, Depaolis M, Hunter JA, et al. Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% in patients with bacterial conjunctivitis: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, 5-day efficacy and safety study. Clin Ther. 2009 Mar;31(3):514-26.