|

An epiretinal membrane (ERM) is a fine layer of tissue that forms on the surface of the retina. Because it has contractile properties, the underlying retina can reshape, leading to visual symptoms of blurred vision, metamorphopsia, macropsia or monocular diplopia that do not always improve with refraction.

The prevalence of ERM varies and may be seen in up to 7% of the population, although the annual incidence of newly identified cases increases in patients with retinal disorders. With improved diagnostic capabilities with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) imaging, clinicians can more easily identify an ERM in the absence of significant visual symptoms—likely indicating the actual incidence is much greater. But being able to identify them earlier doesn’t necessarily mean we need to remove them earlier, if at all.

|

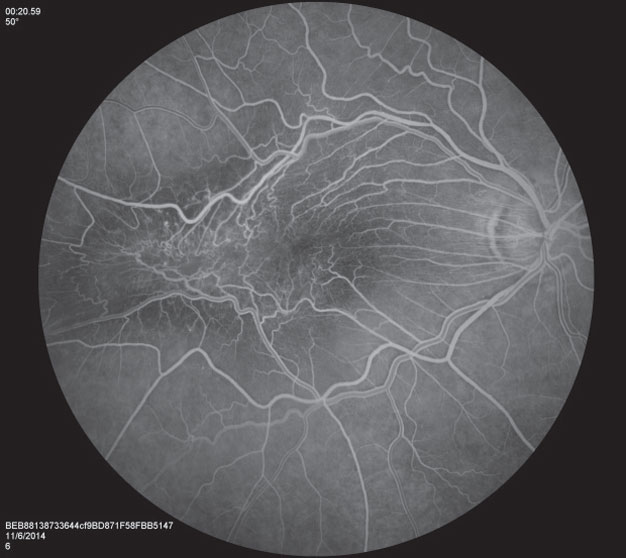

| Fig. 1. The patient’s fundus image reveals a surface ERM in the right eye. |

|

| Fig. 2. FA shows surface retinal traction and vascular tortuosity. |

|

| Fig. 3. FA also highlights the presence of CME. |

ERMs occur secondary to vitreous changes, contraction or an incidental posterior vitreous detachment in most cases, although other potential causes include peripheral retinal breaks, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, trauma, uveitis and intraocular surgery. An ERM can be associated with surface retinal traction that causes lamellar macular changes, partial-thickness macular holes and cystoid macular edema (CME). ERMs rarely cause a full-thickness macular hole, however.

Once an ERM is diagnosed, questions of management and when to refer for retinal surgery are of utmost importance.

ERM management can include medical treatment of any CME with topical steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or surgical removal of the membrane. The primary goal of treatment is to reduce symptoms and any associated frustration. Unfortunately, even with surgical removal some patients will continue to have blurred vision with macropsia, although the metamorphopsia may resolve entirely.

Clinicians often struggle to know when a referral is appropriate for these patients. The top concern for any treating OD is whether the patient has symptoms or is frustrated with their vision. If not, ODs can continue to see these patients once or twice yearly for primary care, SD-OCT imaging and follow up. If the patient is experiencing symptoms and reduced visual quality, a retina referral is warranted. Some retina surgeons require a reduction in visual acuity to a level of 20/60 to 20/80 before considering surgery, although most patients are more bothered by symptoms of distortion than blurred vision, and this experience most often drives the decision to remove an ERM.

Distortion Deterred

Case by Dr. Haynie

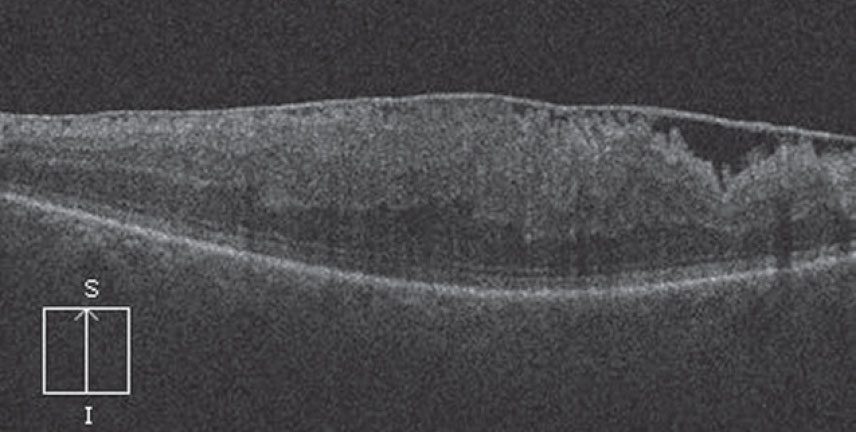

A 74-year-old Caucasian male was referred for an evaluation of poor vision in the right eye for the past year. His medical history included hyperlipidemia treated with Lipitor (atorvastatin, Pfizer). His ocular history included prior cataract surgery in both eyes and retinopexy for a peripheral retinal tear in the right eye. His best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/300 OD, and Amsler grid testing revealed central metamorphopsia. Dilated examination revealed a prominent surface ERM in the right eye (Figure 1), while fluorescein angiography (FA) confirmed surface retinal traction, vascular tortuosity (Figure 2) and cystoid macular edema (Figure 3). SD-OCT demonstrated increased macular thickness with a surface ERM and macular traction (pucker) in the right eye (Figure 4).

|

| Fig. 4. The right eye’s OCT imaging shows both increased macular thickness and macular traction in addition to the surface ERM. |

|

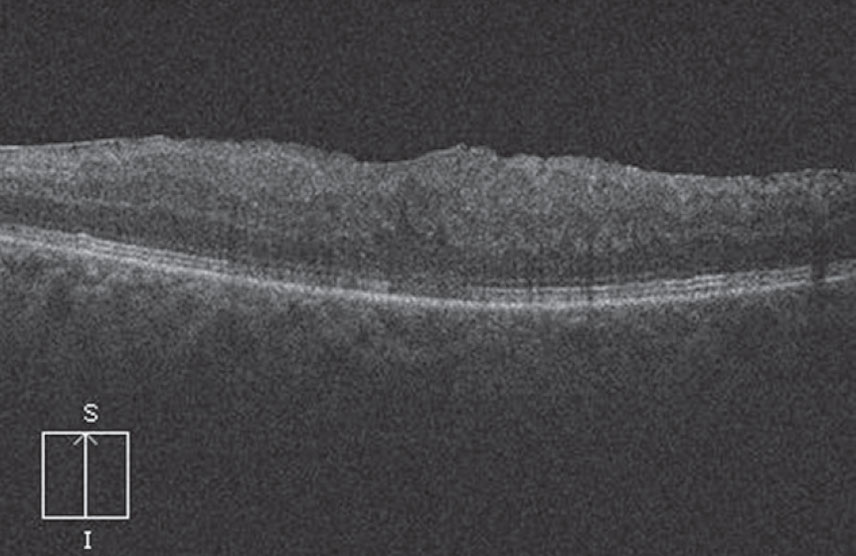

| Fig. 5. Six months post-PPV, the patient’s OCT shows significant improvement: reduced macular thickness, a smooth retinal surface and some restored foveal contour. |

After reviewing the risks, benefits and alternatives to retinal surgery—including that postoperative visual acuity and symptoms may take up to 12 months to reach maximal improvement—he elected to undergo pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with peeling of the ERM and internal limiting membrane (ILM) and fluid-gas exchange.

He was positioned face down during the first 72 hours post-op. After six months, his visual acuity improved to 20/50 OD with resolution of metamorphopsia. SD-OCT images revealed a reduction in macular thickness, a smooth retinal surface and some restoration of the foveal contour (Figure 5).

Membrane Management Compared

Commentary by Dr. Shechtman

The extent of visual impact for the individual patient is what truly drives our retina specialists to proceed with surgical intervention. Overall, most patients experience visual improvement following surgical intervention, although complete restoration of visual function is not always achieved. Thus, when we recommend surgical intervention, the patient’s symptomology is always considered. I often recommend our referring ODs seek a consult when the ERM begins to impact the patient’s daily activity or when they note a correlating visual acuity of less than 20/40. We do not customarily operate on patients with mild and non-progressive symptoms (especially in a patient who is not complaining), as results may be unsatisfactory.

The determination to proceed with surgical intervention varies on an individual basis. We may recommend surgery to a patient whose visual acuity is 20/40 but is significantly bothered by the associated metamorphopsia, while we may simply observe a patient with a visual acuity of 20/60 who is not visually impacted by the ERM. Other considerations may include the status of the contralateral eye (e.g., is the patient a monocular patient?), the potential for further progression (particularly if it is associated with visual deterioration) and progression of structural changes.

Where I practice, treatment for ERM includes PPV with membranectomy (with or without intravitreal Kenalog to identify posterior hyaloid) and with or without ILM peel. If we choose to include ILM peel, we tend to use indocyanine green angiography to stain the ILM.

Surgery is often associated with excellent restoration of the normal retina architecture. However, many variables impact visual restoration, including: onset of symptoms, preoperative symptoms and visual acuity and secondary complications following surgery.

When surgery is recommended, patient education is critical. The patient needs to be aware of possible complications such as iatrogenic retinal breaks, retinal detachments, paracentral choroidal neovascularization or macular hole formation, cataract formation, etc. Furthermore, the patient should be aware of the small possibility of recurrence. Proper expectations regarding long-term visual function recovery are crucial for overall patient satisfaction with the management approach.