Editors note: The following letter from Joe Sicari, president and CEO of Paragon Vision Sciences, is in response to a previously published letter signed by 11 doctors from Canada, the United States, United Kingdom and Australia.

Editor: I read with great interest the letter from Dr. John Rinehart and colleagues, CRT: Is It or Isnt It the O Word? (April 2002). Since Paragon Vision Sciences choice to refer to our contact lens corneal reshaping technology as Corneal Refractive Therapy (CRT) has apparently caused some distress, I thought it might be useful to present our rationale for doing so.

We respect practitioners rights to refer to contact lens

corneal reshaping in any way they choose. Our effort was simply to choose a designation that addressed several issues that surfaced during our consumer and practitioner market research.

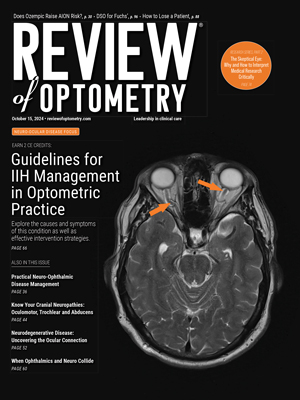

This corneal map shows central flattening achieved with orthokeratology.

First, let me confirm that what Paragon is designating CRT and what some others call orthokeratology are conceptually the same. Both have precisely the same intended outcomecontact lens corneal reshaping to improve refractive error. Here, I will outline some of the reasons Paragon chose to change the designation of this science.

We do believe that Paragon CRT is a superb product with very clear distinctions from all other traditional orthokeratology products. The key points of meaningful differentiation will be disclosed to the eye-care community following final FDA clearance. Until then, I can confidently communicate the single key difference in one word: science.

Secondly, as far as the consumer is concerned, our research was rather conclusive that the terms orthokeratology or ortho-k provided little to no description of the technology. We also learned, as we anticipated, that only a fraction of consumers in our sample had ever heard of orthokeratology or, for that matter, the science of contact lens corneal reshaping. This suggested that a change to some alternate terminology provided a valuable opportunity to educate consumers and support professional eye care.

Among several alternate designations, the term Corneal Refractive Therapy seemed to resonate with consumers. Many consumers in the marketing research study understood the word cornea. Second, the word refractive was more widely understood as having to do with vision than we expected, perhaps because of the broad promotion of refractive surgery. Finally, the term therapy suggested to consumers that some form of continual eye care was required. It was Paragons belief that the notion of continual eye care made good sense for patient eye health, and supported eye-care professionals.

As for the eye-care practitioner: Paragons research indicated moderate to strong feelings of skepticism about orthokeratology or ortho-k. Practitioners had a sense that the claims of the safety and efficacy of orthokeratology were purely anecdotal since, to their knowledge, no scientific studies had been conducted in the 30-40-year history of the modality. Under those conditions, practitioners suggested, such a modality should not be practiced.

Additionally, the research indicated that many practitioners felt that those practicing orthokeratology were a relatively small group outside the mainstream of practice. It is not Paragons position to agree or disagree with these perceptions. What we know is that perceptions, whether fact or not, whether deserved or not, are as real as if they are facts.

At the practitioner level, considering that Paragons goal is to have CRT become a substantial part of the eye-care industry, we did, as Dr. Rinehart, et al. suggested, make a marketing decision. Guilty as charged. It was Paragons contention that the use of the designation orthokeratology or ortho-k would add a significant hurdle to bringing this modality into the mainstream of the professions, and would require considerable time and money to defend. It is a term that had little marketing value and, quite arguably, negative equity. Paragon chose to invest in continued and expanded CRT scientific study instead.

Fourth, there is a difference between the traditional reverse geometry lenses for orthokeratology and Paragon CRT. We believe in the merits of the Paragon CRT product and its associated prescribing and dispensing system. We have completed the most comprehensive scientific research and clinical studies done to date relative to this modality. The FDA Advisory Panel, resulting in a unanimous vote recommending approval, has reviewed these studies. To our knowledge, this alone differentiates Paragon CRT from orthokeratology.

Understand that Paragons scientific work and clinical studies included both the proprietary Proximity Control Technology contained exclusively in the Paragon CRT lens design, and the traditional reverse geometry designs. The FDA Advisory Panel in January recommended both designs for overnight approval. Having completed the clinical studies for both and having the option to market one or both products, Paragon chose the Paragon CRT.

There are specific and significant lens design, prescribing and dispensing system differences between Paragon CRT and the traditional reverse geometry designs. These differences will be made visible to the eye-care community upon final FDA marketing clearance.

We believe that the Paragon CRT design addresses many of the concerns expressed to us by eye-care practitioners who might consider including CRT in their practices. They range from fitting logic and predictability of Paragon CRT to having the scientific and clinical data to support product claims, and supplying an efficient and effective dispensing system to minimize their time while maximizing patient satisfaction. At the end of the day, Paragon understands and believes that any judgment about meaningful differentiation is best left to the eye-care community. In short, the proof will be in the pudding.

Finally, a word about topography: Paragon Vision Sciences and the Humphrey Division of Carl Zeiss Ophthalmic Systems Inc. recently executed a business agreement for the purpose of educating and encouraging eye-care practitioners to use topography in Paragon CRT patient management. Paragons clinical data suggests that topography is not critically important to the actual lens selection and fitting of Paragon CRT. However, we do urge practitioners to investigate using a topographer for taking patient baseline data and for effective and efficient patient follow-up.

I would think that Paragons action to secure a formal business relationship with an ophthalmic equipment company signals our understanding and support of topography in the management of CRT patients. However, Paragon also believes that requiring an eye-care professional to use topography is not within the purview of a product manufacturer. Paragon believes that each practitioner should be supplied the relevant and available scientific data. It is, then, up to the practitioner to decide whether to purchase diagnostic equipment.

In summary, Paragon took what we believed to be a scientific and thoughtful approach to this project for the past seven years. We honor and respect every practitioners right to choose or support what they feel is in their and their patients best interests. I sincerely hope that this information might lead to a better understanding of Paragons approach to this emerging and dynamic opportunity for all of us.Joe Sicari, president and CEO, Paragon Vision Sciences, Mesa, Ariz.

Be Careful What You Take

When Going Out the Door

Editor: I have no doubt that Dr. Anthony Diecidues advice found in Building the Practice, Part I: Your Declaration of Independence (March 2002) is well intentioned. However, if followed it is also likely to result in a lawsuit by your former employer.

Employees must understand that the patient list is the proprietary information of their employer. Irrespective of whether one has a covenant not to compete, using that list, without the permission of its owner, to solicit the business of the employers patients may lead to a claim for misappropriation of trade secrets, conversion of assets and/or breach of fiduciary duty.

The fallacy is in the belief that, just because one performed an exam on a given patient, that the patient now belongs to the employee. The patient does not. These are patients of the employer, who most likely expended considerable time and money to earn their patronage. The recordsthe names and addressesalso belong to the employer, not the employee.

Instead, after leaving employment, one should purchase a commercially available list of the residents near the new practice location and mail them a general announcement. No doubt many of those receiving the announcement will be patients of the former employer, but because the doctor did not use the former employers patient list, this should eliminate claims of misappropriation.

The best advice Dr. Diecidue gives is to contact an attorney. Whether or not there is a covenant not to compete, it is essential that one know what one can legally do to build the new practice. Consult with an attorney early in the process, before you can make any costly mistakes. The few thousand dollars spent with a knowledgeable attorney is likely to save you many times that amount down the road.Craig S. Steinberg, O.D., J.D., Sherman Oaks, Calif. craig@odlawyer.com.

Dr. Diecidue responds: In the case of an employed optometrist, Dr. Steinberg is correct in stating that the patient list is the property of the employer, and permission (although not likely to be granted) is required before an ex-employee uses that list.

In some situations, however, that permission may not be necessary. For example, an independent optometrist practicing adjacent to a retail optical most likely will own the patient records.

Dr. Steinberg brings up an excellent suggestion in purchasing a list of residents. Even better may be a voter-registration list. In most locales this is public domain and available free or at minimal cost.

Neither of us can emphasize enough the importance of having an attorney advise you every step of the way.