|

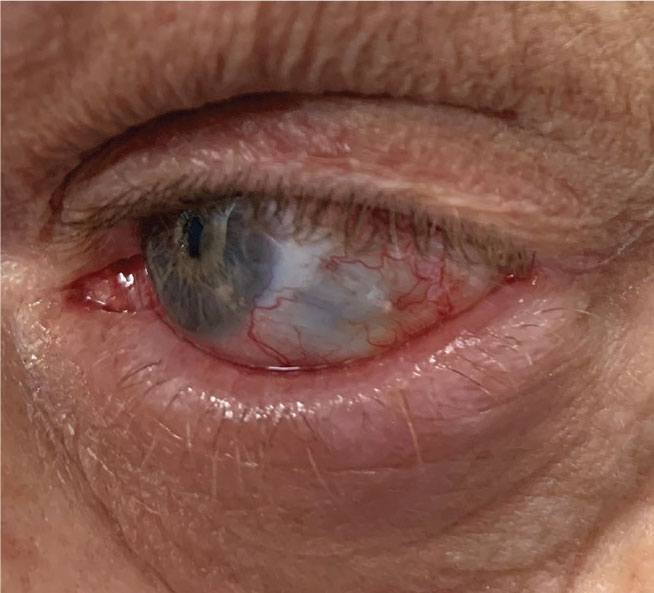

A 59-year-old man presented urgently with a red, painful, photophobic left eye of approximately 10 days duration. His uncorrected visual acuity was 20/40 OD and finger counting OS with no pinhole improvement. His left eye manifested profound deep injection throughout his bulbar conjunctiva. Additionally, there was a mixed papillary and follicular response of the palpebral conjunctiva. There was a grade 3 cell and flare reaction of the left eye with stromal corneal edema and endothelial keratic precipitates.

His crystalline lens manifested an age-appropriate nuclear sclerosis in the right eye but a dense nuclear cataract in the left. His intraocular pressures (IOP)were 18mm Hg OD and 34mm Hg OS. There was also temporal conjunctival and scleral thinning OS and a calcific scleral plaque. His right eye was normal. Cataract and posterior synechia prevented any views of the left fundus.

Based upon signs and symptoms, he was diagnosed with anterior scleritis OS. He was prescribed topical difluprednate 0.05% QID, atropine 1% BID, Combigan (brimonidine/timolol, Allergan) BID and oral ibuprofen 800mg QID PO. His medical history was significant only for diabetes, with no suggestion of autoimmune or rheumatologic diseases. He was referred for medical evaluation with a rheumatologist to find a potential underlying cause.

Painful Reaction

Scleritis is an inflammation of the sclera.1-4 Patients often report ocular pain that may radiate to involve the adjacent head and facial regions. Photophobia and lacrimation are common. Depending on the involvement of the cornea and severity of inflammation, vision can be reduced. While scleritis may be local and idiopathic, most cases are secondary to systemic disease as arthritis, medication side effects or as a complication of ocular surgery.5-7

|

|

Anterior scleritis in a patient post-surgery. Click image to enlarge. |

Although the pathogenesis of scleritis is not entirely understood, evidence points to a deposition of immune complexes within the sclera, leading to a vasculitis with associated inflammatory cell infiltration and edema.8 There typically will be dilation of the scleral vessels as well as the overlying vasculature of the episclera and bulbar conjunctiva.1-4 The affected eye may assume a deep red, almost hemorrhagic appearance.4-6 The presentation may be sectorial but is usually diffuse, differentiating it from the more common and benign episcleritis. Scleritis is bilateral in many cases but is often asymmetric. Corneal involvement in the form of infiltrative stromal keratitis, non-inflammatory corneal thinning or peripheral ulcerative keratitis is possible.9 Glaucoma can occur from inflammation or angle closure secondary to choroidal effusion.10

Necrotizing scleritis is a particularly severe form where the sclera thins to the point that the underlying dark hue of the choroid is visible.11 The most destructive form of necrotizing scleritis is scleromalacia perforans, presenting insidiously without substantial pain or visible inflammatory signs with uveal herniation through a perforated scleral wall.12

Scleritis can be associated with both infectious and non-infectious causes. While the etiology remains idiopathic for many cases of scleritis, most are associated with a causative systemic disease. The most common related disorders are rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, tuberculosis, herpes zoster and syphilis.13 Assume that there is an underlying systemic disease until proven otherwise. Patients should undergo a comprehensive medical evaluation. A rheumatologist is the best comanagement source.

Treatment

Topical therapy alone is typically insufficient to manage most cases of scleritis and should be considered adjunctive to ameliorate initial acute symptoms. Initial topical therapy involves potent cycloplegia with atropine 1% BID and topical steroids such as prednisolone acetate 1% Q2h to QID or difluprednate TID-QID.

Systemic treatment begins with oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for mild to moderate, non-necrotizing anterior scleritis.1 Therapy may include ibuprofen 600mg to 800mg QID or naproxyn sodium 250mg to 500mg TID. If insufficient, oral prednisone 60mg to 80mg PO QD can be given for two to three days and then slowly tapered to 10mg to 20mg daily. Immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine or methotrexate are sometimes necessary in the most severe or recalcitrant cases.14,15

Based upon lack of insurance, the patient was resistant to rheumatologic consultation or any systemic medical testing. During the course of his therapy and follow-up, he casually mentioned that he had undergone a cosmetic conjunctival whitening procedure called “I-BRITE” approximately five years prior in another state. Initially, this elicited no recollection, but later investigation of this procedure proved very informative and ultimately the likely cause.

Dangers of Whitening

Eye whitening procedures were introduced around 2008 and have been offered as a treatment of chronic conjunctival hyperemia. Patients variably undergo conjunctivectomy with topical mitomycin C (MMC) 0.02% application to achieve a whitened appearance from bleaching of the avascular sclera. In some procedures, MMC is combined with antiangiogenic bevacizumab during the procedure.

|

|

Scleral thinning in a patient with scleritis. Click image to enlarge. |

The literature has noted complications of cosmetic eye whitening, including chronic conjunctival epithelial defects, scleral thinning, avascular zones in the sclera, dry eye syndrome and diplopia requiring strabismus surgery.16 One review of 1,713 patients undergoing cosmetic whitening procedures noted an overall complication rate of 83%, of which 55.6% cases were considered severe. These severe complications included fibrovascular conjunctival tissue proliferation, scleral thinning with calcified plaques, IOP elevation, diplopia and recurrence of hyperemic conjunctiva.17

Another study found that the average time from the procedure to diagnosis was 51 months, and all patients had unilateral findings. There was no underlying systemic autoimmunity or infectious etiology found. The authors noted that, because of the large area of the ocular surface that is treated in eye whitening with MMC, the necrotizing scleritis that can ensue may be more extensive and severe than the surgically induced necrotizing scleritis following other periocular surgeries.18

One study reported on a patient who developed bilateral necrotizing scleritis within the nasal region of both eyes. The patient also developed calcified plaques within the areas of scleromalacia, along with an epithelial corneal defect four years after undergoing I-BRITE. It found a delayed development of complications.19

In an attempt to raise awareness of the complications for surgical conjunctival eye whitening procedures, one study reviewed the medical records of patients who received cosmetic conjunctivectomy plus postsurgical topical MMC treatment to eliminate conjunctival injection in a single facility. They found that of the 48 patients undergoing the procedure, 44 had complications related to the procedure. These complications included fibrovascular conjunctival adhesion at the muscle insertion site, chronic dysfunctional tear syndrome, abnormal vessel growth, lymphangiectasis, adhesions of Tenon’s capsule and the conjunctiva at the extraocular muscle insertion site, extraocular muscle fiber exposure and diplopia.20

For this patient, topical and oral anti-inflammatory therapy, physical removal of the calcific plaque and cataract extraction ultimately were able to restore ocular health and visual function after several months. He was informed that a similar situation could still develop in his fellow eye as the I-BRITE procedure was done bilaterally.

Be aware of cosmetic surgical conjunctival whitening procedures that can have an unacceptably high attendant complication rate and risk of serious vision-threatening outcomes, even years after the procedure.

Dr. Sowka is an attending optometric physician at Center for Sight in Sarasota, FL, where he focuses on glaucoma management and neuro-ophthalmic disease. He is a consultant and advisory board member for Carl Zeiss Meditec and Bausch Health.

1. Rachitskaya A, Mandelcorn ED, Albini TA. An update on the cause and treatment of scleritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(6):463-7. 2. Moreland LW, Curtis JR. Systemic nonarticular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: focus on inflammatory mechanisms. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39(2):132-43. 3. Galor A, Thorne JE. Scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33(4):835-54. 4. Kirkwood BJ, Kirkwood RA. Episcleritis and scleritis. Insight. 2010;35(4):5-8. 5. Ahn SJ, Oh JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical features, predisposing factors, and treatment outcomes of scleritis in the Korean population. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2010;24(6):331-5. 6. Zlatanović G, Veselinović D, Cekić S, et al. Ocular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis-different forms and frequency. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2010;10(4):323-7. 7. Smith JR, Mackensen F, Rosenbaum JT. Therapy insight: scleritis and its relationship to systemic autoimmune disease.Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(4):219-26. 8. Fong LP, Sainz de la Maza M, Rice BA, et al. Immunopathology of scleritis. Ophthalmology 1991; 98(4):472-9 9. Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS, Jabbur NS, Baltatzis S. Ocular characteristics and disease associations in scleritis-associated peripheral keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120(1):15-9. 10. Ikeda N, Ikeda T, Nomura C, Mimura O. Ciliochoroidal effusion syndrome associated with posterior scleritis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2007;51(1):49-52. 11. Moreno Honrado M, del Campo Z, Buil JA. A case of necrotizing scleritis resulting from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cornea. 2009;28(9):1065-6. 12. Wu CC, Yu HC, Yen JH, et al. Rare extra-articular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis: scleromalacia perforans. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21(5):233-5. 13. Pavesio CE, Meier FM. Systemic disorders associated with episcleritis and scleritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001; 12(6):471-8. 14. Kaplan-Messas A, Barkana Y, Avni I, Neumann R. Methotrexate as a first-line corticosteroid-sparing therapy in a cohort of uveitis and scleritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2003;11(2):131-9. 15. Hillenkamp J, Kersten A, Althaus C, Sundmacher R. Cyclosporin A therapy in severe anterior scleritis. 5 severe courses without verification of associated systemic disease treated with cyclosporin A. Ophthalmologe 2000; 97(12):863-9. 17. Tran AQ, Hoeppner C, Venkateswaran N, et al. Complications of cosmetic eye whitening Cutis. 2017 Sep;100(3):E24-E26. 16. Lee S, Go J, Rhiu S, Stulting RD, et al. Cosmetic regional conjunctivectomy with postoperative mitomycin C application with or without bevacizumab injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(3):616-22. 18. Ji YW, Park SY, Jung JW, et al. Necrotizing scleritis after cosmetic conjunctivectomy with mitomycin C. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;194:72-81. 19. Moshirfar M, McCaughey MV, Fenzl CR, et al. Delayed manifestation of bilateral scleral thinning after I-BRITE procedure and review of literature for cosmetic eye-whitening procedures. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:445-51. 20. Rhiu S, Shim J, Kim EK, Chung SK, Lee JS, Lee JB, Seo KY. Complications of cosmetic wide conjunctivectomy combined with postsurgical mitomycin C application. Cornea. 2012;31(3):245-52. |