| About this Series To help optometrists strengthen their protocols for managing conditions that require ongoing—perhaps life-long—care, this series explains the steps to take after confirming a diagnosis, from day one through long-term management. Each installment in the five-part “Now What?” series will cover a different chronic condition: My Patient Has Recurrent Corneal Erosion...Now What? My Patient Has Diabetic Retinopathy...Now What? July—AMD |

For many clinicians, the diagnosis and treatment of scleritis can be daunting tasks. This troubling condition frequently requires an arduous course of treatment and brings significant risk for destruction of ocular structures and permanent vision loss. The diagnosis of scleritis is based primarily on clinical observation and the patient’s presenting constellation of symptoms. Pain will be the hallmark, and it is constant, may radiate to the periorbital region and will be exacerbated by eye movement.1 A duration of one to two months is not uncommon, as the onset of scleritis is often insidious and patients may not seek care until the pain becomes severe.2 Slit lamp and dilated fundus examinations, optical coherence tomography (OCT), B-scan ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) are all helpful diagnostic tools to confirm even the most difficult cases.

Although diagnosis is often straightforward, properly classifying and identifying the cause of a patient’s scleritis isn’t always easy—and yet it is critical in determining the treatment regimen and obtaining the best possible visual outcome.

|

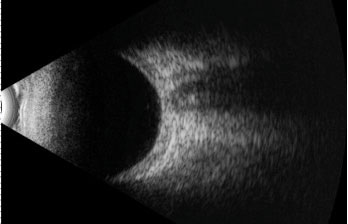

| This B scan ultrasound demonstrates scleral thickening in the absence of the pathognomonic “T sign”. |

Classification

After the initial diagnosis, the next essential step in managing scleritis is determining the type the patient is manifesting. Clinical signs and symptoms vary significantly between anterior and posterior, diffuse and nodular, necrotizing and non-necrotizing scleritis. The likelihood and type of ocular sequelae is also determined according to type.

Diffuse anterior scleritis is the most common but relatively benign form of scleritis and presents with extensive redness and edema.2,3 Inflammation of the trabecular meshwork may occur, causing trabeculitis and secondary elevated intraocular pressure (IOP).4 In isolated anterior scleritis, no posterior segment findings are present. It is uncommon for these patients to progress to more aggressive forms.

Nodular anterior scleritis is characterized by localized areas of inflammation that present as distinct, tender nodules on the sclera. The nodules are deep red, immobile and can vary in size and number. Of patients diagnosed with nodular anterior scleritis, 42% present with multiple nodules and 20% have superimposed conjunctival congestion and episcleritis involving the entire anterior episclera.2,5

Necrotizing anterior scleritis is the most severe and destructive form of the disease, posing a significant threat to vision. Compared with the other forms, this condition more commonly affects females and has a higher incidence of associated systemic inflammatory conditions. Necrotizing scleritis is characterized by intense pain, which may become excruciating with time. Localized or generalized necrosis is the result of areas of intense vasculitis that close the deep episcleral plexus. Progression may occur rapidly to expose the choroid. These patients have acute congestion of the conjunctival, episcleral and scleral vasculature surrounding the necrotic areas. Inflammation commonly spreads to involve the cornea (peripheral ulcerative keratitis), ciliary body (anterior uveitis) and trabecular meshwork (ocular hypertension).3,5,6

|

| This slit lamp photo demonstrates diffuse anterior scleritis in a 58-year-old male with a subsequent negative systemic workup. The inflammation resolved completely with oral indomethacin. |

Scleromalacia perforans is a rare form of necrotizing anterior scleritis without adjacent inflammation caused by an obliterative arteritis in the deep episcleral plexus. Patients are typically asymptomatic with no pain or injection but may present with blurred vision from high astigmatism caused by loss of scleral integrity. The sclera will be thin and may have a white, marble- or porcelain-like appearance. The choroid can become exposed, and staphyloma may form, particularly in the presence of elevated IOP. Consistent with those diagnosed with necrotizing scleritis, these patients typically have long histories of systemic inflammatory disease.3,5,6

Posterior scleritis represents scleral inflammation posterior to the insertion of the rectus muscles. The inflammation may be localized or diffuse in nature, similar to diffuse and nodular scleritis.7 An associated anterior scleritis may be present, or the posterior scleritis may occur in isolation. If isolated, anterior segment findings are rarely present, though an inflamed sclera may be visible in gaze extremes. Presentation varies widely based on location and severity, but vision loss and pain are common to all posterior scleritis diagnoses.8 Patients with posterior scleritis may experience diplopia or decreased visual acuity due to swelling around the optic nerve or retinal changes. Extraocular motilities will exacerbate the patient’s pain, and in the gaze extremes you may note inflammation of the posterior sclera. Other findings in posterior scleritis include chorioretinal granulomas and serous retinal detachments.9 Retinal OCT can be helpful in differentiating retinal pathology and determining whether macular edema is present.

B-scan ultrasonography is essential in visualizing the posterior scleral thickening and fluid accumulation that can occur. The scan will show increased thickness of the eye wall, whether widespread or localized. Scleral thickness greater than 2mm is considered abnormal.7 Fluid may accumulate in the episcleral space and can extend posteriorly around the optic nerve. This fluid in Tenon’s capsule forms the characteristic “T sign” considered pathognomonic for posterior scleritis.1,8

Posterior scleritis patients are typically younger, and a unilateral presentation occurs twice as often as bilateral involvement.6,8

|

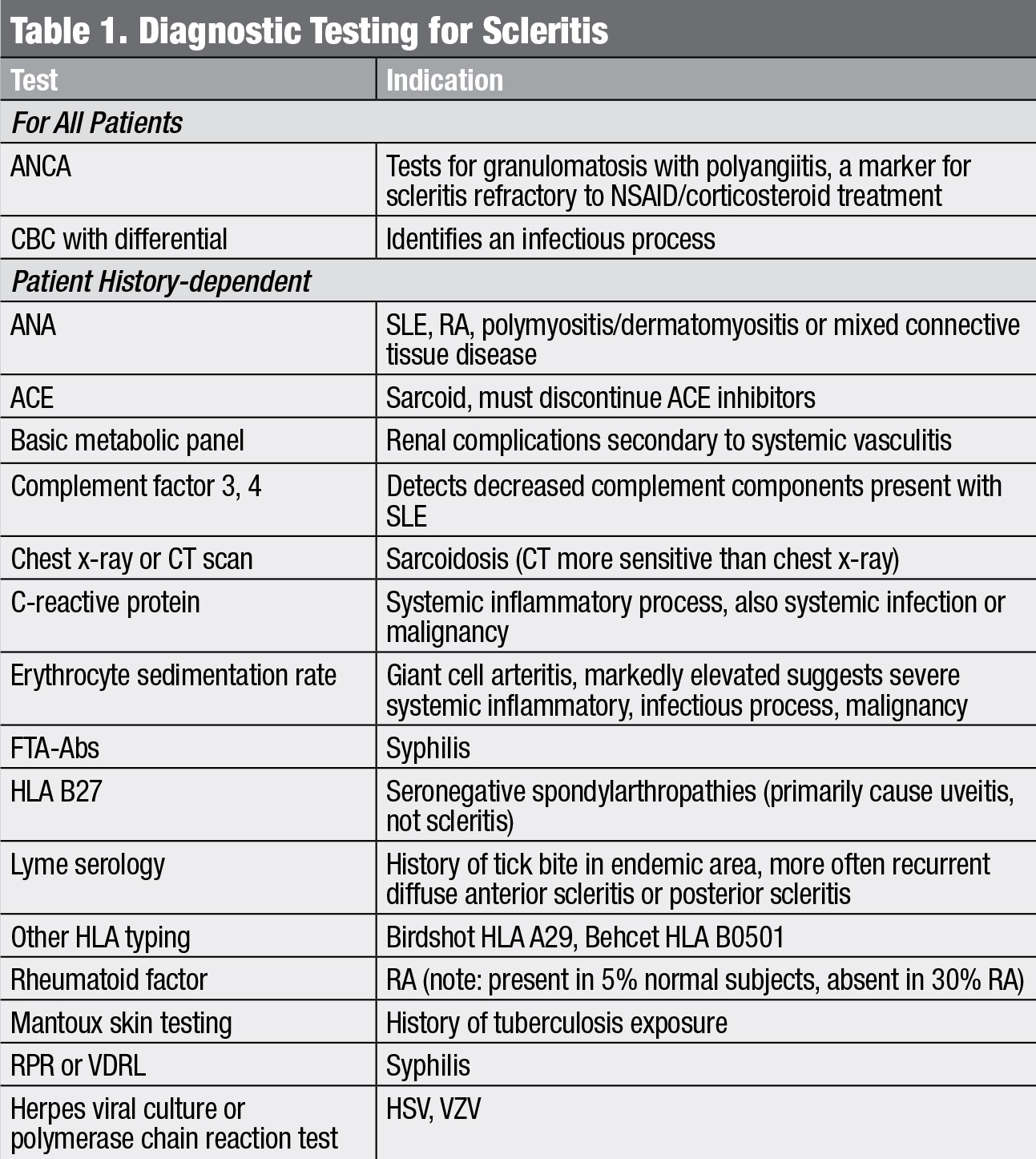

| Diagnostic testing for scleritis. Click table to enlarge. |

Cause

Once you have identified the type of scleritis, your next step is determining the cause of the patient’s inflammation. While many cases of scleritis are idiopathic, up to 50% will have an associated systemic disease.10 Accounting for 40% to 50% of cases, autoimmune conditions are the most common conditions associated with scleritis. While rheumatoid arthritis (RA), particularly with vasculitis such as Wegener granulomatosis, occurs most frequently, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and relapsing polychondritis are all associated with scleritis.11

Infectious scleritis is rare, comprising 4% to 10% of cases. While this is a relatively low percentage, it is imperative to rule out infectious etiologies prior to initiating treatment, particularly with steroids. Recent trauma or surgery may serve as a source for infection, as can extension of a corneal keratitis.3,12 Potential pathogens include viral, fungal and bacterial, although the most common agent is herpes zoster, implicated in 8% of infectious scleritis cases. Herpetic cases are typically unilateral, sudden onset and associated with moderate to severe pain.3,13 Any systemic history of herpes simplex, Lyme, tuberculosis or syphilis is a potentially significant finding.14 Infectious etiologies should be addressed with an antimicrobial agent appropriate to the condition.

|

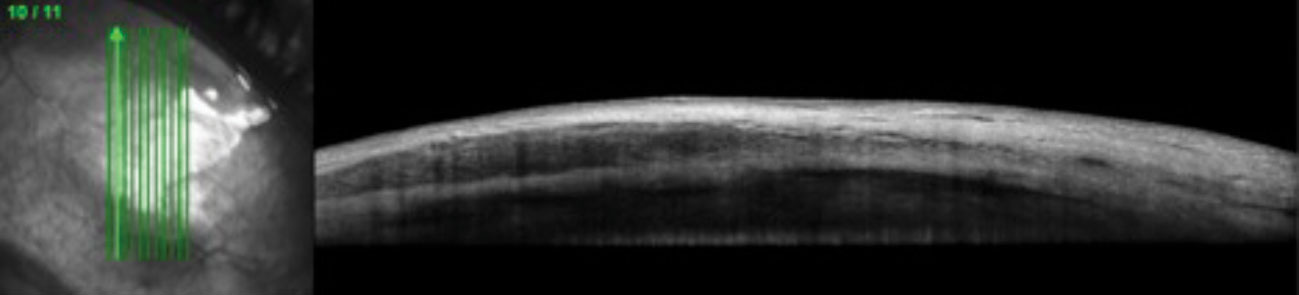

| This 51-year-old female with a systemic history of rheumatoid arthritis was diagnosed with nodular anterior scleritis. Anterior segment OCT through the scleral nodule superior nasal OD demonstrates low reflectivity spaces consistent with edema. Click image to enlarge. |

Surgically-induced necrotizing scleritis (SINS) is a non-infectious granulomatous inflammation that can occur months, even years, after intraocular surgery. Procedures most commonly associated with SINS include pterygium removal, cataract extraction and scleral buckle.3,14,15 It can be difficult to differentiate from postoperative infectious causes of scleritis; thus, cultures, biopsies and empiric treatment with antibiotics is critical, particularly following pterygium surgery. Of those who develop SINS, 75% have undergone two or more surgical procedures.16

Malignancies do not cause a scleritis in the truest sense, but conjunctival tumors, lymphoma or malignant deposits from melanoma may mimic the inflammation seen in scleritis. In the absence of a therapeutic response, an early biopsy should be considered to identify these rare cases.3,5

While a patient’s medical history and clinical picture can provide a clear indication of a potential cause, certain baseline laboratory investigations, and possibly imaging, are indicated. Regardless of presentation, clinicians should obtain a complete blood count (CBC) and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test for all scleritis patients prior to initiating treatment (Table 1). The CBC is imperative for identifying infectious processes. ANCA positivity is a marker for vasculitis, which typically has a grimmer clinical picture.3 Even in the absence of clinical evidence of vasculitis, a positive ANCA may be a marker for refractory scleritis.3 Additional systemic workup should be guided by patient history, review of systems and the physical examination.

|

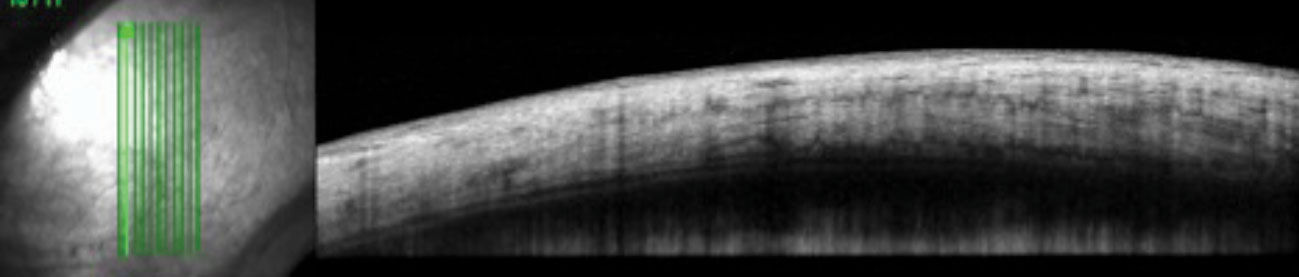

| The control image of the same quadrant in the patient’s fellow eye shows homogenous reflectivity throughout the layers. Click image to enlarge. |

Management

Now that you have determined the type and cause of the scleritis, it’s time to establish an initial treatment protocol. Systemic treatment is required because scleral inflammation is rarely affected by topical treatments.17 A number of patients respond to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) alone, but one study showed that 67% of patients required either high-dose glucocorticoids or a combination of high-dose glucocorticoids and another immunosuppressive agent to establish control.11

Diffuse and nodular types of scleritis are the most likely to respond to NSAIDs alone. Frequently used agents include indomethacin, naproxen, ibuprofen, piroxicam, diclofenac and celecoxib. Studies show nonselective COX inhibitors (indomethacin) and selective COX inhibitors (celecoxib) are equally effective in controlling inflammation in 78% to 81% of scleritis patients.18 In Europe, flurbiprofen is an option, but many investigators maintain that indomethacin is more effective than any other available NSAID.11,19 Thus, your first step will likely be prescribing indomethacin 25mg orally four times a day. Be aware that gastrointestinal side effects from indomethacin occur in 22.2% of patients. Patients at high risk for NSAID gastropathy may benefit from a selective COX inhibitor or be prescribed a histamine H2 receptor antagonist (e.g., ranitidine) or a proton pump inhibitor.18

Necrotizing anterior scleritis, posterior scleritis and refractory anterior scleritis all necessitate more aggressive treatment. For these patients, initial therapy will consist of oral corticosteroids given as a one-time dose of oral prednisone 1mg/kg up to a maximum of 80mg. For these forms of scleritis, many practitioners advocate for a combined treatment of steroids plus an immunosuppressive agent from the start.

Subconjunctival corticosteroid injections in the management of scleritis have historically been met with controversy due to reports of scleral thinning, though a more recent study shows complete resolution with no cases of scleral melting.3,20,21 Ocular hypertension is the main side effect encountered with the use of subconjunctival injections and may require hypotensive agents or surgical intervention.21

Be sure to coordinate care with rheumatology and uveitis specialists when necessary—especially for patients presenting with necrotizing scleritis, scleromalacia perforans and posterior scleritis—as rheumatologic disease should be considered in all scleritis patients. Immunosuppressive agents are often indicated when treating these forms and should be administered by providers well versed in their use. A variety of immunosuppressive agents can aid in managing inflammation while decreasing the need for corticosteroids, including antimetabolites (methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil), alkylating agents (chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide), T-cell inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus), tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab) and the chimeric monoclonal antibody rituximab.19,23-26

When referring to a specialty provider, include a letter rather than merely forwarding copies of your electronic record. A summary referral letter, which is far more concise, particularly with multiple documented visits related to the scleritis, ensures the specialist knows what tests you have completed and what treatment you initiated. Referrals to subspecialists for corneal, retinal or glaucoma care can be urgent, and providing a summary of care and current ocular status of the patient can help the receiving provider triage the patient and offer timely care. The referral letter should include:

- The reason for referral

- Patient’s age, sex and race

- Patient medical and ocular history (particularly rheumatologic history and prior ocular inflammatory episodes)

- Any diagnostic testing performed and the results

- Timeline of care, including treatments, patient response and complications

Don’t hesitate to specify any diagnostic hypotheses you have developed, as this can provide the specialist with additional perspective, aiding in their diagnostic and treatment decisions.27

|

| Here's a quick guide on scleritis. Click image to download. |

Follow up

The patient’s follow-up schedule varies based on the severity of their signs, symptoms and response to treatment. For mild cases, initial follow ups should be performed every one to two weeks, while severe cases may need to be monitored as frequently as daily when risks of perforation or sight threatening complications exist. Once you note treatment response, follow-up intervals may be extended to monthly or longer. Follow-up visits should include visual acuity, anterior segment exam, Goldmann tonometry and a dilated fundus exam. B-scan should be repeated for any patient with posterior scleritis or for those patients you suspect are progressing.

For diffuse and nodular patients showing improvement on indomethacin, the dosage may be reduced to 25mg orally three times daily until the inflammation has subsided. Indomethacin is typically continued for at least one month, after which it can be discontinued. During NSAID treatment, patients should be monitored for possible gastrointestinal and renal effects. Patients who do not improve on indomethacin may be switched to a different NSAID such as naproxen 250mg to 500mg orally twice daily. If the patient continues to see no improvement, initiate systemic steroids consistent with the treatment regimen suggested for more severe forms.

Continue oral prednisolone at the initial dosage for no longer than four to six weeks until the scleritis is quiescent, then taper in an individualized manner to minimize potential corticosteroid morbidity.3,11,28 Although the exact dosages will vary, an appropriate taper schedule would be to reduce the steroid dosage by 10mg each week from 60mg to 40mg, by 5mg increments weekly from 40mg to 20mg, by 2.5mg weekly from 20mg to 10mg and by 1mg increments every two weeks from 10mg to 5mg.11

Many patients may require an additional immunosuppressive agent, including those who have persistent inflammation after two to three weeks of high-dose steroid treatment, patients who progress to a more severe variant of the disease (demonstrating signs consistent with necrotizing or posterior scleritis) and patients who cannot tolerate steroid treatment.15 Patients typically continue immunosuppressive therapy until they reach a disease-free state for six months to one year.

Extended observation is necessary for these patients so that medications can be adjusted in a manner individualized to the patient’s therapeutic response. Even with proper treatment, a significant number of patients will have a recurrence of inflammation and must continue to be followed closely even after reaching a disease-free state.

Complications may arise throughout the management period both from the scleritis and the treatment regimen. Research shows one-fifth of patients—particularly those with necrotizing scleritis—will experience ocular hypertension stemming from a possible combination of trabeculitis, ciliary body rotation and steroid response.5 Clinicians should strongly consider consulting with an anterior segment/cornea specialist for patients with any degree of scleral or corneal thinning, as grafting may be necessary. Cataracts will occur in 17% of patients over time following the scleritis.5 Some degree of permanent vision loss occurs in 10% of anterior diffuse scleritis, 25% of nodular scleritis and 75% to 85% of necrotizing or posterior scleritis.11,29 A referral to low vision can be of great value for patients with long-term sequelae and vision loss following the resolution of inflammation but can also be considered during active treatment to maximize the patient’s usable vision.

Scleritis is a complex, potentially vision-threatening condition that must be managed aggressively. Clinicians can reduce ocular and systemic morbidity with timely treatment, which can include a combination of non-steroidal, steroidal and immunosuppressive agents. These patients frequently require a multidisciplinary approach and benefit greatly from cooperative care between optometrists, ophthalmology subspecialists and rheumatologists.

Dr. Sanford is an attending optometrist at the Memphis VA Medical Center.

1. Levin LA, Albert DM. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010. 2. Watson PG, Hayreh SS. Scleritis and episcleritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60(3):163-91. 3. Diaz JD, Sobol E, Gritz D. Treatment and management of scleral disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(6):701-17. 4. Wilhelmus KR, Grierson I, Watson PG. Histopathologic and clinical associations of scleritis and glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;91(6):697-705. 5. Okhravi N, Odufuwa B, McCluskey P, et al. Scleritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(4):351-63. 6. Cunningham E, McCluskey P, Pavesio C, et al. Scleritis. Ocular Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24(1):2-5. 7. McCluskey PJ, Watson PG, Lightman S, et al. Posterior scleritis: clinical features, systemic associations, and outcome in a large series of patients. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(12):2380-86. 8. Lavric A, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Majumder PD, et al. Posterior scleritis: analysis of epidemiology, clinical factors, and risk of recurrence in a cohort of 114 patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24(1):6-15. 9. Benson WE. Posterior scleritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32(5):297-316. 10. Sims J. Scleritis: presentations, disease associations and management. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88(1046):713-18. 11. Jabs DA, Mudun A, Dunn JP, Marsh MJ. Episcleritis and scleritis: clinical features and treatment results. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):469-76. 12. Bowling B. Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2015. 13. Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Molina-Prat N, Doctor P, et al. Clinical features and presentation of infectious scleritis from herpes viruses: A report of 35 cases. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1460-4. 14. Ramanaden ER, Raiji VR. Clinical characteristics and visual outcomes in infectious scleritis: a review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:2113-22. 15. Doshi RR, Harocopos GJ, Schwab IR, et al. The spectrum of postoperative scleral necrosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(6):620-33. 16. O’Donoghue E, Lightman S, Tuft S, et al. Surgically induced necrotising sclerokeratitis (SINS)- precipitating factors and response to treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76(1):17-21. 17. Lachmann SM, Hazleman BL, Watson PG. Scleritis and associated disease. Br Med J. 1978;1:88-90. 18. Kolomeyer AM, Ragam A, Shah K, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors in the treatment of chronic non-infectious, non-necrotizing scleritis and episcleritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamml. 2012;20(4):293-99. 19. Tuft SJ, Watson PG. Progression of scleral disease. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(4):467-71. 20. Ahn SJ, Oh JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical features, predisposing factors, and treatment outcomes of scleritis in the Korean population. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2010;24(6):331-35. 21. Sohn EH, Wang R, Read R, et al. Long-term, multicenter evaluation of subconjunctival injection of triamcinolone for nonnecrotizing, noninfectious anterior scleritis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(10):1932-37. 22. Rachitskaya A, Mandelcorn E, Albini T. An update on the cause and treatment of scleritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:463-67. 23. Sen N, Sangave A, Hammel K, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of active scleritis. Canadian J Ophthalmol. 2009;44(3):e9-12. 24. Gangaputra S, Newcomb CW, Liesegang TL, et al. Methotrexate for ocular inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2188-98. 25. Suhler EB, Lim LL, Beardsley RM, et al. Rituximab therapy for refractory scleritis: results of a phase I/II dose-ranging, randomized, clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):1885-91. 26. Albini TA, Rao NA, Smith RE. The diagnosis and management of anterior scleritis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45(2):191-204. 27. Bachali A, Sahli H, Tekaya R, et al. Analysis of referral letters to rheumatology consultation in Tunisia. The Egyptian Rheumatologist. 2017;39(3):179-82. 28. Albini TA, Zamir E, Read RW, et al. Evaluations of subconjunctival triamcinolone for nonnecrotizing anterior scleritis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(10):1814-20. 29. Pakrou N, Selva D, Leibovitch I. Wegener’s granulomatosis: ophthalmic manifestations and management. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35(5):284-92. 31. Calthorpe CM, Watson PG, McCartney AC. Posterior scleritis: a clinical and histological survey. Eye. 1988;2:267-77. 30. Snell R, Lemp M. Clinical anatomy of the eye. Malden: Blackwell; 1989. |