Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema can be a confounding complication of even the most carefully planned cataract procedure. Although pseudophakic CME doesn’t occur a lot postop, this means it’s not studied a lot, so surgeons often must go on their own clinical acumen when treating it.

In this article, experts explain how they work up and treat cases of pseudophakic CME, from the mild to the recalcitrant.

Risk Factors

The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Preferred Practice Patterns defines this condition as retinal thickening of the macula due to a disruption of the blood-retinal barrier, causing leakage from the perifoveal retinal capillaries. The leakage leads to fluid accumulation in the retina, distorting the architecture of the photoreceptors and potentially causing central vision loss.

How big a problem is this among cataract surgery patients? Phoebe Lin, MD, PhD, a retina and uveitis specialist and an associate professor at Casey Eye Institute, at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, notes that some studies have found that about 2.4 percent of small-incision phaco patients develop pseudophakic CME. “Of course, people with pre-existing diabetic retinopathy can get diabetic macular edema,” she says. “However, even without a risk factor like that, it still seems to occur about 2 percent of the time. Why it occurs when you don’t have diabetic retinopathy or a prior history of inflammation is a little unclear.”

Sruthi R. Arepalli, MD, a uveitis and vitreoretinal surgeon at Tennessee Retina in Nashville, points out that it’s difficult to say exactly how many cataract surgery patients develop postop CME. “It depends on how you define it,” she explains. “For example, you can define it clinically. That means looking at it with a slit lamp; I can see the edema, and it’s causing some sort of visual decline. But you can also find cysts on OCT or fluorescein angiogram; those may not be visually significant, and they may not be things that we need to treat. As a result, risk calculations based on OCT and fluorescein angiograms are higher than numbers based on clinical exam.”

Naturally, surgeons would like to know which patients are more likely to develop CME post-cataract surgery. “Risk factors for CME after cataract surgery include diabetic retinopathy; an epiretinal membrane; a history of uveitis; and/or a prior history of macular edema related to something like a retinal vein occlusion,” notes Chirag P. Shah, MD, MPH, a vitreoretinal surgeon at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston, an assistant professor at Tufts University School of Medicine and a lecturer at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Arepalli lists a number of things that lead her to warn patients that postop CME is a possibility. “First, patients with diabetes are at higher risk, even if they don’t have retinopathy, because their vessels are leakier,” she says. “Second, if a patient has a very small pupil or posterior synechiae, I know there will be pupillary manipulation during the cataract surgery; that can release a cascade of cytokines, resulting in CME. Third, a person with an epiretinal membrane is more at risk. Fourth, if I’m following a patient for retinal vein occlusion, even if they haven’t had macular edema in the past, their risk is higher; like patients with diabetes, their vessels are leakier than normal. Also, if the patient has a history of uveitis, their eye already tends to be more inflamed, making them more susceptible.

“Other things that can increase the risk of postop CME include differences in eye architecture,” she continues. “If the posterior capsule ruptures during the surgery for any reason and the vitreous is unstable—it comes forward or even gets stuck in the cataract wound—that can lead to CME. The risk also increases if there’s an iris-sutured lens, or an anterior chamber lens that’s causing some chafing and moving around, or the lens placed in the bag becomes dislocated and falls back.

“I always tell patients, as well as our residents and fellows, that CME following cataract surgery can occur in both complicated and uncomplicated surgeries,” she says. “It involves the release of prostaglandins and inflammatory markers, causing an influx of fluid via leakage from the perifoveal capillaries and other sources. It can happen even when the surgery goes flawlessly, but it happens more often in patients who require a lot of manipulation inside the eye or have some sort of a surgical complication.

“Also,” she adds, “some reports have suggested that patients who are on prostaglandins such as latanoprost may be predisposed to CME development, although this is a subject of debate.”

Dr. Lin points out that most cataract patients do get some limited degree of postop inflammation. “Unfortunately, there’s no test you can do ahead of time to predict who’s going to get pseudophakic CME,” she says. “Luckily, it’s not very common, and typically it’s self-limiting. However, that means it’s not something anyone would perform a huge study on to try to identify the risk factors. Pseudophakic CME can present with scant vitreous and/or anterior chamber cells and optic disc leakage.”

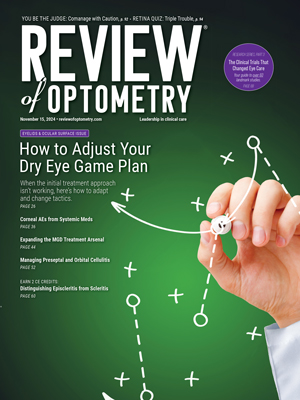

|

| A 73-year-old male previously followed for dry macular degeneration was sent for evaluation for supposed pseudophakic CME versus conversion to neovascular macular degeneration following cataract surgery. Fundus examination revealed drusen in the macula and edema, but no signs of choroidal neovascular membrane on optical coherence tomography or fundus examination. Inferotemporally, the vessels appeared sclerotic and a fluorescein angiogram was useful in diagnosing a branch retinal artery occlusion with macular edema which was treated with anti-VEGF therapy. |

Initial Treatment

“It’s not uncommon to develop minimal macular thickening after cataract surgery,” Dr. Shah points out. “CME will usually manifest within a few months after the operation. Often, it’s mild and not visually significant, causing no symptoms. It may be apparent on OCT or angiography, but not to the patient. Typically, I only treat if the patient is symptomatic from CME, or if it’s significant on OCT. If it’s not affecting or harming the vision, it’s reasonable to monitor it.”

Dr. Shah believes any treatment should be based on the apparent cause of the macular edema. “I employ a stepwise approach,” he explains. “First, I do a comprehensive exam to determine if there are any other underlying risk factors for the macular edema. If it’s just Irvine-Gass pseudophakic macular edema, it will often respond well to topical anti-inflammatory drops; once the macula is dry, I gradually taper the patient off the drops. If the cataract surgery exacerbated a patient’s diabetic macular edema, one can start treatment with anti-inflammatory drops. However, one might need to treat the diabetic macular edema. The same is true for other underlying causes such as retinal vein occlusion or macular puckering.”

Dr. Lin says patients referred to her typically have developed unexpected residual CME about one month after cataract surgery. “In most cases these patients are already on a topical steroid like prednisolone and an NSAID like ketorolac or diclofenac,” she says. “A steroid with an NSAID is a pretty reasonable first-line treatment for pseudophakic CME; it’s routinely employed for diabetic patients post-phaco. Usually, patients are tapered off by one month, although if the referring physician still sees CME, they might prolong the use of those drops.

“When I see the patient, treatment is typically a step-wise protocol, but individualized,” she adds. “If the patient isn’t already on prednisolone and ketorolac, I usually try that for about a month.”

“Most surgeons I’ve encountered feel very comfortable starting with a topical NSAID—generally ketorolac, though there are other options as well—and Pred Forte, four times a day,” says Dr. Arepalli. “Generally, they follow the patient for a month to see if it starts to get better. If it doesn’t, they may send the patient to a specialist.

“If I see a patient with a little bit of pseudophakic CME, and their vision is generally 20/30 or 20/20, I’ll first do a fluorescein angiogram and OCT to make sure I’m really treating pseudophakic CME,” she continues. “If it really is CME, but the patient has good vision and only trace fluid, we can treat or we can watch for a while—whichever the patient prefers. I usually give them about a month to show that they’re improving before moving ahead with treatment. If the patient gets better over time, I usually keep them on a four-times-a-day regimen until their fluid resolves. Then I’ll start to taper off the drops.

“I don’t advise tapering before the fluid is completely gone,” she adds. “I’ve tried that, and in some patients the fluid starts to come back.”

Why do many surgeons opt for using steroids and NSAIDs together? “NSAIDs are anti-inflammatory, but they’re not very potent medications, in terms of treating cells or macular edema,” says Dr. Lin. “However, they’re not completely inactive, and they don’t cause elevated eye pressure. They can treat mild CME, and they have nice adjunctive properties when used along with topical steroids; they can sometimes reduce the amount of steroid you use. Some patients are steroid responders, so adding NSAIDs can be a benefit to the patient, lowering their steroid burden and thus reducing steroid-related side effects.”

“I use both Pred Forte and Acular because published studies have looked at steroid drops alone, vs. topical NSAIDs alone, vs. both used together,” notes Dr. Arepalli. “Although there are no randomized controlled trials looking at this question, it’s clear that the greatest benefit comes when both are used together. The steroid drops also let us see if the patient has a steroid response, in case we consider more invasive steroids in the future.”

Should you treat preoperatively? Sruthi R. Arepalli, MD, a uveitis and vitreoretinal surgeon at Tennessee Retina in Nashville, says she believes deciding whether to start the patient on drops prior to cataract surgery is largely a question of surgeon comfort. “I’ve seen some cataract surgeons who start drops before the surgery to try to limit inflammation, and some who don’t,” she notes. “I think either choice is appropriate. Presumably, the choice is based on what they’ve seen in their patient population. “If you’re seeing a patient who has a risk factor for postop CME such as diabetes, an epiretinal membrane, a previous retinal vein occlusion or something leading you to expect a complicated surgery or postop course, then placing the patient on a topical NSAID and Pred Forte four times a day in the week or so preceding surgery is totally reasonable,” she says. “This regimen is usually pretty inexpensive and well-tolerated, with a very low side-effect profile. “Of course,” she adds, “if the patient is uveitic, it makes sense to defer to their uveitis provider to make sure the eye is totally quiet before you do the cataract surgery. You don’t want to be entering a hot eye.” -CK |

Stepping It Up a Notch

“If a patient referred to me is already on a topical steroid and an NSAID and still has CME, that tells me the problem is more severe than what those two drops can handle,” says Dr. Lin. “My next step would be to put them on a more potent steroid drop. There’s one called difluprednate, which is more highly penetrating, and it can also be used at a lower frequency than prednisolone. So, I’ll typically escalate to that first and give the CME about one month to improve. We don’t put patients on that drop initially because it has a higher rate of elevated IOP as a side effect.”

Dr. Lin says that if the severity of the CME is beyond what she thinks can be treated by difluprednate alone, then she might offer a posterior sub-Tenon’s steroid injection or an intravitreal steroid injection. “I also do a very thorough bilateral exam for other signs of inflammation,” she notes.

“For instance,” she continues, “bilateral inflammation would suggest that the patient might have an underlying uveitic process that wasn’t recognized previously. Or, I might see other signs such as chorio-retinal scarring or other signs of prior inflammation. In that situation, I’ll take a step back and start working up the patient for causes of uveitis. However, if it’s run-of-the-mill pseudophakic CME, and the patient doesn’t have any other signs of infectious uveitis or bilateral, systemic endogenous uveitis, then I’ll go up the stepladder of steroid treatment.”

Dr. Shah says that if topical treatment doesn’t resolve the CME, he’ll also consider a sub-Tenon’s Kenalog injection. “This is usually unnecessary,” he says. “However, if it’s needed it will improve the CME in most cases, and it can be repeated. In the small portion of patients for whom a sub-Tenon’s Kenalog injection isn’t helpful, I’d consider an intravitreal steroid injection next.”

Dr. Arepalli says if the topical drops are well-tolerated but produce insufficient response, then she’ll discuss other options with the patient. “Those options would include periocular corticosteroids,” she says. “Those have been shown to be effective in cases of refractory CME.

“Intravitreal triamcinolone has also been used and shown to be effective,” she continues. “The downside of using intravitreal triamcinolone is that it has a short therapeutic window, so you have to keep giving it to patients. And once you start going down the intravitreal route, you’re talking about a more potent corticosteroid with a greater likelihood of triggering an IOP increase. If the patient still isn’t responding, or they have refractory CME that keeps coming back, then you can start discussing long-lasting drug depots, like Ozurdex or Yutiq, which have been approved for posterior uveitis.”

“I do think if it gets into the arena of the patient needing increasing dosages or injections, that’s best left to a retinal or uveitis specialist,” she adds. “They’re very experienced at monitoring the retina and looking for clues about other reasons this might be happening.”

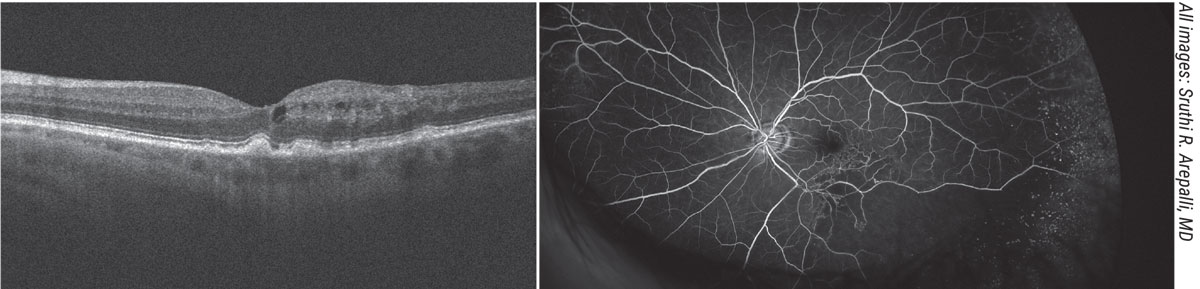

|

| A 68-year-old female presented one month after cataract surgery in the left eye (left) with vision decreased to 20/40 and a small amount of cystoid macular edema. She was treated with a combination of Pred Forte and a topical NSAID, with resolution of the fluid at six weeks (right). |

Treating With Anti-VEGF

One option that may be appropriate to use with some patients is anti-VEGF injections. “Some patients have presumed postop macular edema, but without the other signs of intraocular inflammation,” notes Dr. Lin. “For instance, they don’t have anterior chamber cell or vitreous cell along with the macular edema; they look quiet. Those are good candidates for anti-VEGF.

“I’ve also used anti-VEGF for patients who are very sensitive to steroid-induced elevated eye pressure,” she continues. “Or, I get a referral where other things have been already tried without success. The patient may already have had a spike in eye pressure while using the regular postop drops. In that case, I may go straight to anti-VEGF treatment.”

“I’d consider anti-VEGF injections for patients with macular edema as a result of diabetic retinopathy or retinal vein occlusion,” notes Dr. Shah. “Furthermore, intravitreal steroids might be necessary.”

In this situation, Dr. Lin says it makes sense to treat with close observation. “You usually wouldn’t inject more than once a month, so you’d be bringing the patient back monthly to see how they respond and whether the edema recurs,” she says. “This is not a chronic, progressive disease like macular degeneration; it’s typically self-limited to a year at most. If it lasts more than a year, it’s usually something else completely.

“For that reason,” she explains, “the treatment wouldn’t follow a macular degeneration protocol. You wouldn’t need to have a three-month start-up phase and then go to treat-and-extend. In any case, by the time you’re trying anti-VEGF with one of these patients, the problem has existed for several months, so they’re near the end of the postop inflammation—assuming the problem really is pseudophakic CME.”

Dr. Arepalli says she reserves anti-VEGF injections for use as a last resort. “I save anti-VEGF injections for a more selective group of patients—those I think might have more of a VEGF-driven problem,” she explains. “That would include diabetic patients and those who’ve had retinal vein occlusions or macular degeneration—something that makes me think there’s a cascade of inflammation, and that VEGF would be a good target.”

The other question regarding anti-VEGF injections is: Who should perform the injections? Dr. Shah says he believes the decision about whether to perform intravitreal injections oneself or refer to a retina specialist is mostly a question of availability. “Where I practice, in Boston, cataract surgeons typically don’t do intravitreal injections,” he notes. “They usually refer to retinal specialists, who are readily available. On the other hand, in some parts of the country, comprehensive ophthalmologists do their own anti-VEGF injections because the nearest retinal specialist might be hours away. I think it depends on the region in which one practices.”

If anti-VEGF injections are given, Dr. Arepalli favors having them performed by a surgeon who’s comfortable administering them. “Typically, that means someone who’s been trained to do them, and trained to deal with their possible complications,” she says. “That’s why I wouldn’t want to do glaucoma surgery; I don’t do it every day. If there’s no one available besides the cataract surgeon, and the surgeon feels comfortable doing it, and does injections routinely, I think that’s reasonable. But I’d always prefer to see injections done by someone who does them regularly.”

Systemic Treatment

Dr. Lin points out that most cases resolve within six months or a year. “That’s why I go with local therapy rather than systemic therapy,” she explains. “Some cases are more prolonged, but at that point you’re thinking the patient must have some kind of underlying inflammatory process.

“Sometimes it takes additional testing to tease out the fact that the patient has an underlying inflammatory condition,” she notes. “There have been times when we thought a patient had pseudophakic CME, but we weren’t sure because the patient had such a complex surgical history. “Usually within two visits I’d do a fluorescein angiogram and discover that the patient had bilateral asymmetric inflammation from an underlying uveitic condition such as sarcoidosis; it just wasn’t detected by run-of-the-mill testing and examination. It happened to worsen postoperatively.”

“If the patient has uveitis,” says Dr. Shah, “you can start with topical anti-inflammatory drops, but the patient might need more potent anti-inflammatory treatment to resolve the edema. This could include periocular or intravitreal steroids, or systemic immune suppression. It depends on the overall picture.”

Dr. Lin adds she never uses a systemic immunosuppression treatment for typical pseudophakic CME. “I only go that route if the patient has other signs of inflammation,” she explains. “Those are the patients who were misdiagnosed as having pseudophakic CME.”

Strategies for Success

Surgeons offer these tips for ensuring the best possible outcome:

• If possible, do a preop dilated exam of both eyes. “Sometimes the patient has a dense cataract, making this impossible,” Dr. Lin notes. “However, a bilateral dilated exam can identify an indolent, undetected factor such as diabetic retinopathy or an underlying uveitic process, which you obviously want to know before proceeding with the surgery.”

• Consider adding the possibility of CME to your consent. “As surgeons, we typically focus on the most consequential possible complications when getting patient consent,” notes Dr. Lin. “We may not consent for some things like inadvertent ptosis after surgery, or pseudophakic CME, because they’re usually not as visually consequential as something like endophthalmitis. However, it’s good to let the patient know that such things can occur. You can explain that there’s a possibility of CME, even if the surgery goes perfectly and everything looks great ahead of time. It’s an unpredictable potential complication.”

Dr. Arepalli says she believes it’s reasonable that the possibility of postop CME be included in the consent discussion. “It’s a tough call because providers have to walk a line,” she admits. “You want to give the patient all the information you can, but you don’t want to overwhelm them, and there’s no way to talk about every single possible complication. However, I think it’s very reasonable to mention this when a patient has high-risk factors.”

• Set realistic patient expectations. “If your patient has a pre-existing condition that could trigger postop CME, I think it’s appropriate to have a quick conversation to explain that they’re at higher-than-average risk of CME, and tell them why,” says Dr. Arepalli. “You can explain that if it occurs—which is possible even when the surgery goes perfectly—it could prevent them from reaching their ideal vision, and you might have to send them to a retina specialist. It’s a good way to set realistic patient expectations.”

Dr. Lin agrees. “I explain that it can continue for six months, in some cases up to a year,” she notes. “I emphasize that we’re typically able to get it under control. It’s not something anyone will have to deal with for the rest of their lives.”

“Also,” Dr. Arepalli adds, “make sure they understand that if CME occurs, it’s not your fault. Patients in the cataract surgery age range usually have friends whose cataract surgery left them with 20/20 vision on day one, so they’ll be frustrated if their postop course is longer and more complicated. You don’t want the patient to think that postop CME means you did something wrong during the surgery.”

• If you find CME, do a very thorough work-up. “I’ve seen patients present for a pseudophakic CME evaluation and it turns out to be something else,” says Dr. Arepalli. “Of course it is inflammation, but it may turn out to be associated with an underlying condition that should be treated. In one patient the problem turned out to be sarcoidosis; they needed systemic immunosuppression to quiet it down permanently. I’ve caught anterior chamber cell, vitreous cell, chorioretinal scarring and vasculitis. Those can all happen in the setting of pseudophakic CME—albeit rarely.

“I also do very careful retinal exams,” she continues. “I’ve seen post-cataract-surgery patients who develop a retinal vein occlusion or some other sort of occlusive event that comes with fluid, and it looks like pseudophakic CME. It’s really important to rule those things out. I also look for other reasons for intraretinal and subretinal fluid. If the person has dry macular degeneration, have they converted to the wet kind? Should we get a fluorescein angiogram again and make sure there’s no choroidal neovascularization?

“The point is that it’s important to make sure that nothing else is going on in the eye,” she concludes. “If some kind of active inflammation is happening, we need to figure out why it exists. We can treat it locally, but if the patient needs systemic treatment, we should be doing that as well. So I’ve learned to be very diligent about working these patients up.”

Drs. Lin, Shah and Arepalli report no relevant financial ties to any product mentioned in the article.