Upon reviewing the case with the patient, you notice that the history your front office staff relayed to you changed a bit—his visual acuity curiously measures 20/20 OU.

After reading through his medical history, you learn that the patient had a car accident in a neighboring state––one he was lucky to survive. The patient reported “a cracked ribcage, broken leg and a punctured lung.” Since the accident, the patient has experienced excruciating ocular and neck pain (10 out of 10 on the severity scale).

He tried ibuprofen, but it hasn’t helped. The patient mentions that 800mg ibuprofen upsets his stomach. Interestingly, it seems that the only medication that can help with the eye pain is brand-name OxyContin (oxycodone HCl, Purdue Pharma).

After a comprehensive eye exam with ancillary testing, you cannot determine a rational explanation for the patient’s severe ocular pain. So, what can be done to help this individual?

Drug-Seeking Behavior

Primary care optometrists routinely treat eye conditions with confidence and success. As we’re called on to treat more medical eye conditions and provide postoperative surgical care, we should anticipate a proportionate increase in patient requests for pain medications. Managing pain beyond topical or over-the-counter preparations can be intimidating––especially considering that opioids are some of the most commonly abused prescription medicines.1-3

Illicit and prescription drug abuse certainly isn’t a new problem. Nonetheless, because prescription pain medications are commonly abused, it’s important to know which agents you can prescribe and how long to prescribe them. Also, it is essential to learn and recognize the most common signs of drug-seeking behavior.

Controlled substance abuse typically involves use of pain medications for their pleasurable side effects rather than prescribed analgesic purposes.1,3 Each year, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration releases its National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).3 The most recent report was released in December 2012. Using data gathered from 67,500 respondents age 12 and older, the NSDUH indicated that:3,4

• Nearly 8.7% of respondents abused an illicit drug or misused a psychotherapeutic medication (i.e., pain relievers, stimulants, tranquilizers) in the past month.

• The second most misused substances are prescription psychotherapeutic medications.

• Nearly 1.7 million Americans met the clinical criteria for dependence upon psychotherapeutic medications. Only marijuana exhibited a higher prevalence of dependency.

• About 2.4% of Americans are taking prescribed medications for non-therapeutic purposes.

• When considering prescription psychotherapeutic medications, the incidence of misuse has decreased slightly (2.4% in 2011, down from a high of 2.9% in 2006).

Another major concern is the illicit redistribution of prescription medications.3,5 They can be shared with family and friends, sold or even exchanged (especially name-brand narcotics) for other illegal substances.2,6,7 Patients who attempt to acquire prescription medications for non-medicinal intent are termed “drug-seekers.”7,8 Potentially enabling drug-seeking behavior could make some optometrists hesitant to prescribe controlled substances for pain management, despite being appropriately licensed and qualified within their state.

Controlled Substances

A “controlled substance” is a drug that has been declared to be illegal for sale or use in the open market, but can be dispensed under a physician’s prescription. The basis for control and regulation is to decrease the risk of addiction, abuse, physical and mental harm or death, as well as to protect the public from dangers associated with the actions of those who have used these substances.4,9 (Alcohol, tobacco and caffeine––the three most consumed drugs in the United States––are excluded.)

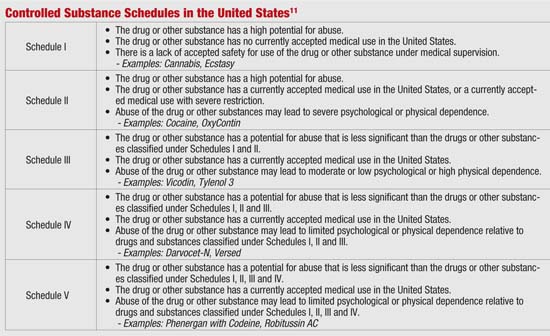

The original Controlled Substances Bill, submitted in 1969, addressed issues involving supply, education, research, rehabilitation, training and communication.10 Its legacy was categorization of controlled substances into schedules depending on their medical usefulness, potential for abuse and relative safety (see “Controlled Substance Schedules in the United States,” above). The schedule in which a substance is placed determines how stringently it is controlled and regulated. For example, street drugs like methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA [a.k.a., “ecstasy,” “E” or “X”]) have no medical use and are categorized as Schedule I agents––the most closely regulated class.

Controlled Substances and Eye Care

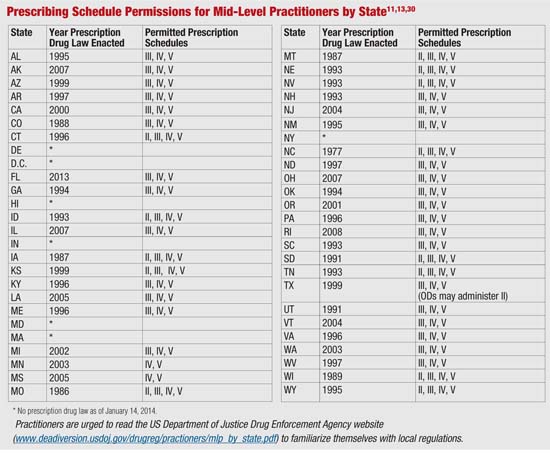

Currently, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classifies optometrists as “mid-level practitioners”—a designation reserved for clinicians who are not veterinarians, physicians, dentists or podiatrists, but are licensed, registered or otherwise permitted to dispense a controlled substance in practice.11 Mid-level practitioners’ prescribing restrictions on controlled substances vary from state to state, and place limits on drug schedule availability, prescribing duration and number of refills.11-13 This is meant to help curtail abuse and/or diversion for illicit use.

Even with these practitioner restrictions in place, patients may decide to abuse or sell their controlled prescriptions to others. For this reason, it is essential to remain alert for drug-seekers, drug-seeking behavior or “doctor shopping.”8,14

To stay abreast of the most current information, refer to your local state board prescription drug guidelines and the DEA’s Office of Diversion Control website: www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugreg/practioners.11

Recognize Drug-Seeking Behavior

Patients who misuse prescription painkillers may be of any age or socioeconomic background.6-8,15 The most common chief complaints associated with patients who exhibit drug-seeking behavior include headache, back pain and dental pain. These symptoms are easily feigned and difficult to evaluate.2,16

On the other hand, patients may present with valid reasons for experiencing these symptoms and request pain relief.2,16,17 A few genuinely painful ocular-related conditions include:

• Scleritis

• Post-herpetic neuralgia and trigeminal nerve pain

• Headache or jaw/tooth pain secondary to arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy

• Acanthamoeba keratitis

• Corneal abrasions and chemical injuries

Keep in mind that patients have different thresholds of pain tolerance for the same injury. Labeling an individual as a “drug seeker” is a diagnosis of exclusion. Such a potentially damaging label should only be assigned after careful examination with appropriate testing and history.

Experienced drug seekers are known to call several offices looking for same-day appointments, often late in the afternoon. Once a drug seeker arrives, he or she may not be able to name prior eye care providers without prompting. Also, the individual may mention that he or she is leaving town early the next morning. This often makes follow-up testing or consultation with previous providers and pharmacies very difficult.16

Prescriptions for narcotic pain medications should not be written at the first examination of a suspected drug seeker.2 As previously mentioned, such individuals often request brand-name pain medications or report a “mysterious” allergy to generic pain medications in order to secure greater street resale value.5,8,9,14

Occasionally, drug seekers attempt to offer an impressive history, intricately describing a very severe initial injury that occurred several years ago. Patients who fabricate such injuries tend to change their stories throughout the examination, so be sure to listen for inconsistences.

Other considerations include how forthcoming the patient is during the history.2,18 Questions that can help identify drug seekers include:

• “When did the symptoms first appear?”

• “If the reported pain is a result of an injury, what was the nature of the injury and when did it occur?”

• “Which other health care providers have you seen about this condition, and when?”

• “Which pharmacy would you prefer us to call a prescription into?” (This lets the patient know you will not be giving them a written prescription that can be altered).

Keep in mind that calling previous health care providers or pharmacists can provide important information about the patient’s “injury” and other characteristics.2

Unlike a patient who sincerely exhibits symptoms, drug seekers often present with a cacophony of improbabilities––a constellation of behaviors and medical history that is difficult to confirm or seems unlikely.2 Often, erratic behavior is evident before the exam. So, be prepared to develop a rational evaluation plan for the cause of the patient’s pain.2,6,8

A patient presenting with extreme pain (10/10 on a conventional pain scale) should exhibit some form of functional or cognitive impairment from the moment of his or her arrival.2 The level of impairment for a patient genuinely in pain should remain consistent throughout the examination. Further, reports of pain intensity from both the patient and accompanying spouse or other family members should be consistent (e.g., a 3/10 at home should not suddenly escalate to 10/10 in the office).

Other warnings include pain descriptions that seem embellished, incongruous and/or anatomically incorrect.2,6,7 For example, a patient may describe intense eye pain and photophobia. While you examine him or her for ocular signs, you employ direct ophthalmoscopy and different types of indirect ophthalmoscopy. Then, he or she may give varied responses to the same stimuli from different instruments––clues that the symptoms are disingenuous.

Drug seekers may become conspicuously flattering, especially when they receive the requested prescription.16 Other telling signs include disappointment at the suggestion of non-pharmacological treatment. If the patient expresses disappointment or agitation upon recommending spectacles for headache relief or non-narcotic medications for postoperative pain, strongly suspect drug-seeking behavior.2,16

| A Brief History of US Drug Laws

In 1970, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act and the Controlled Substances Act were passed in an effort to curtail illegal use of drugs in the United States.10,20-22 The origins of the Controlled Substances Act can be traced back to the late 1800s, when several American cities enacted ordinances designed to combat opium dens and the use of other unauthorized narcotics, hallucinogenics and cocaine.10,20,22 The first major federal drug laws were passed in 1906. What resulted was a patchwork of statutes and regulatory agencies. Over time, it became evident that more coordinated reform was needed. In the late 1960s, the Bureaus of Narcotics and Drug Abuse Control merged to form the Bureau of Narcotic and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD). Then, in 1973, the BNDD merged with several other government agencies to create what we know today as the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). |

| Tools to Combat Drug-Seeking Behavior

• PDMPs. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs are designed to support proper use of controlled substances, while deterring diversion.19,23,24 They also may be helpful in identifying drug interactions. These programs are not administered on the national level, and vary from state to state. Likewise, determining which agency oversees program administration and who has access to the information within the PDMP is at each state’s discretion. In addition, not all states presently have a PDMP in place. In an effort to eliminate drug diversion and improper use of controlled substances, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs has amended its regulations to participate in state-run PDMPs.25 • REMS. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy is a method of managing serious, known drug risks. The program is administered on a national level by the FDA, which has required a REMS for all extended-release and long-acting opioid analgesic drugs. The drugs pertaining to REMS include extended-release oral dosages of hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, analgesic methadone and tapentadol. A REMS is also required for transdermal fentanyl patches used in long-term pain relief.26 • ADMs. The development of Abuse Deterrent Medications has been challenging. In 2005, the College on Problems of Drug Dependence was tasked to look at methods to decrease prescription drug abuse.27 Since then, multiple pharmaceutical companies have been investigating how to make medications with a high abuse potential relatively “tamper proof.” The underlying belief behind ADM research is that by making such medications resistant to crushing for the purposes of injecting or snorting, it will reduce the likelihood of abuse or diversion.27-29 |

Address Drug-Seeking Behavior

When you believe that a patient is exhibiting drug-seeking behavior, your response should be firm but non-accusatory. Make an effort to consider his or her particular situation seriously. Patients who believe that they are being judged could become agitated or even confrontational.2

You may wish to offer the patient a non-narcotic pain medication. If he or she questions you, explain why you believe that this medication will be equally effective for the pain. And, if rebuffed, you can always offer a copy of that day’s visit note or patient chart and arrange for a second opinion with a consulting physician. This documentation confirms that you didn’t ignore the patient’s pain, but rather expressed a difference in opinion that required an ancillary consultation.

Illicit narcotic pain medication use and diversion is detrimental to the patient and the public at large. Writing a prescription for controlled substances––even in limited quantities and/or for short duration––should be carefully considered. Any negative patient reaction to the suggestion of using lower-schedule substances or non-narcotic pain medications should be noted. If necessary, access your state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program and follow the FDA-mandated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy when prescribing controlled substances in these cases.

Complex chronic pain is a real condition that can be easily confused with drug seeking. There is always the possibility that your suspicion is wrong and the patient has a legitimate reason for pain management that was not evident during your exam. Above all, take care of the patient and stress that your decisions are being made with the highest regard to his or her safety.2

Often, these steps are not necessary. Most patients are not drug seekers and those who are don’t want to raise suspicions or cause alarm before attempting to obtain pain medications from another doctor in the same geographic area.1,2,7,8

Since 1976, when the first therapeutic law for optometry was passed in the United States, optometrists have proven to be competent care providers. Subsequently, other states have instituted therapeutic drug laws for optometry.13,19 Because there is no single federal prescribing law governing optometrists, each practitioner must learn the specific prescribing authority of the state or states in which he or she practices.

Prescription drug addiction is a chronic medical condition. Narcotic agents for pain management have strong addictive properties. Drug-seeking behavior is a manifestation of addiction, not a reflection on that person’s character. In order to truly care for these patients, drug counseling may be necessary. Patients who truly need long-term pain medication will do best under the supervision of a licensed, accredited and well-regarded pain management clinic.8,14,16-18

|

|

Dr. Meers practices at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System in Seattle. Dr. Alldredge works at Pacific Cataract and Laser Institute in Portland, Ore.

They thank Katie Meers, RNC, of Tacoma, Wash., and Terri Oneby, OD, of Albuquerque, NM, for their contributions to this article.

1. Beck M. Doctors Challenge: How real is that pain? Wall Street Journal. July 5, 2011.

2. Pretorius RW. A systematic approach to identifying drug-seeking patients. Fam Pract Manag. 2008 Apr;15(4):A3-5.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Facts: Nationwide Trends. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/nationwide_0.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2013.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Facts: Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medications. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/prescription-over-counter-medications. Accessed December 6, 2013.

5. Thompson CA. Prescription drug misuse highlighted as national problem. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001 Jun 1;58(11):956, 960.

6. Grover CA, Close RJ. Quantifying drug seeking behavior: a case control study. J Emerg Med. 2012 Jan;42(1):15-21.

7. Grover CA, Elder JW. How frequently are classic drug-seeking behaviors used by drug-seeking patients in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2012 Nov;13(5):416-21.

8. McCaffery M, Grimm MA, Pasero C, et al. On the meaning of “drug seeking.” Pain Manag Nurs. 2005 Dec;6(4):122-36.

9. Garcia A. State laws regulating prescription of controlled substances. Balancing the public health problems of chronic pain and prescription painkiller abuse and overdose. J Law Med Ethics. 2013 Mar;41 Suppl 1:42-5.

10. Shapiro RS. Legal bases for the control of analgesic drugs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1994 Apr;9(3):153-9.

11. US Department of Justice: Drug Enforcement Administration. Mid-level Practitioners Authorized by State. Available at: www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugreg/practioners/. Accessed December 6, 2013.

12. Betses M, Brennan T. Abusive prescribing of controlled substances. N Engl J Med. 2013 Sep 12;369(11):989-91.

13. Cooper SL. News from the American Optometric Association. 1971-2011: Forty-year history of scope expansion into medical eye care. Available at: http://newsfromaoa.org/2012/03/23/1971-2011-forty-year-history-of-scope-expansion-into-medical-eye-care/. Accessed December 6, 2013.

14. Pierce GL, Smith MJ. Doctor and pharmacy shopping for controlled substances. Med Care. 2012 Jun;50(6):494-500.

15. Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008 Jan 2;299(1):70-8.

16. US Department of Justice: Drug Enforcement Administration. Don’t be Scammed by a Drug Abuser. Available at: www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/brochures/drugabuser.htm#whattodo/. Accessed December 6, 2013.

17. Arnstein P, Herr K. Risk Evaluation and mitigation strategies for older adults with persistent pain. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013 Apr;39(4):56-65; quiz 66-7.

18. Craig DS. The pharmacists’ role in patient-provider pain management treatment agreements. J Pharm Pract. 2012 Oct;25(5):510-6.

19. Reed L. Pharmaceutical practice management. J Am Optom Assoc. 1998 Apr;69(4):241-54.

20. McAllister WB. The global political economy of scheduling: the international-historical context of the Controlled Substances Act. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Oct 5;76(1):3-8.

21. Spillane JF. Debating the Controlled Substances Act. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Oct 5;76(1):17-29.

22. Courtwright DT. The Controlled Substances Act: how a “big tent” reform became a punitive drug law. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 Oct 5;76(1):9-15.

23. Mutembi A, Warholak TL, Hines LE, et al. Assessing patients information needs regarding drug-drug Interactions. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013 Jan-Feb;53(1):39-45.

24. Logan J, Liu Y, Paulozzi L, et al. Opioid Prescribing in emergency departments the potentially inappropriate prescribing and misuse. Med Care. 2013 Aug;51(8):646-53.

25. Department of Veterans Affairs. Disclosure to participate in state prescription drug monitoring programs. Interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2013 Feb 11;78(28):9589-93.

26. US Department of Health and Human Services. US Food & DrugAdministration. List of Extended-Release and Long-Acting Opioid Products Required to Have an Opioid REMS. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm251735.htm. Accessed December 6, 2013.

27. Bannwarth B. Will abuse-deterrent formulations of opioid analgesics be successful in achieving their purpose. Drugs. 2012 Sep 10;72(13):1713-23.

28. Romach MK. Update on tamper resistant drug formulations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 Jun 1;130(1-3):13-23.

29. Kirsh K. Characterization of prescription opioid abuse in the United States: Focus on route of administration. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2012 Dec;26(4):348-61.

30. The Florida Senate. Practice of Optometry. Bill #: CS/CS/HB 239. Available at: www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2013/0239/Analyses/h0239d.HHSC.PDF. Accessed December 6, 2013.