|

|

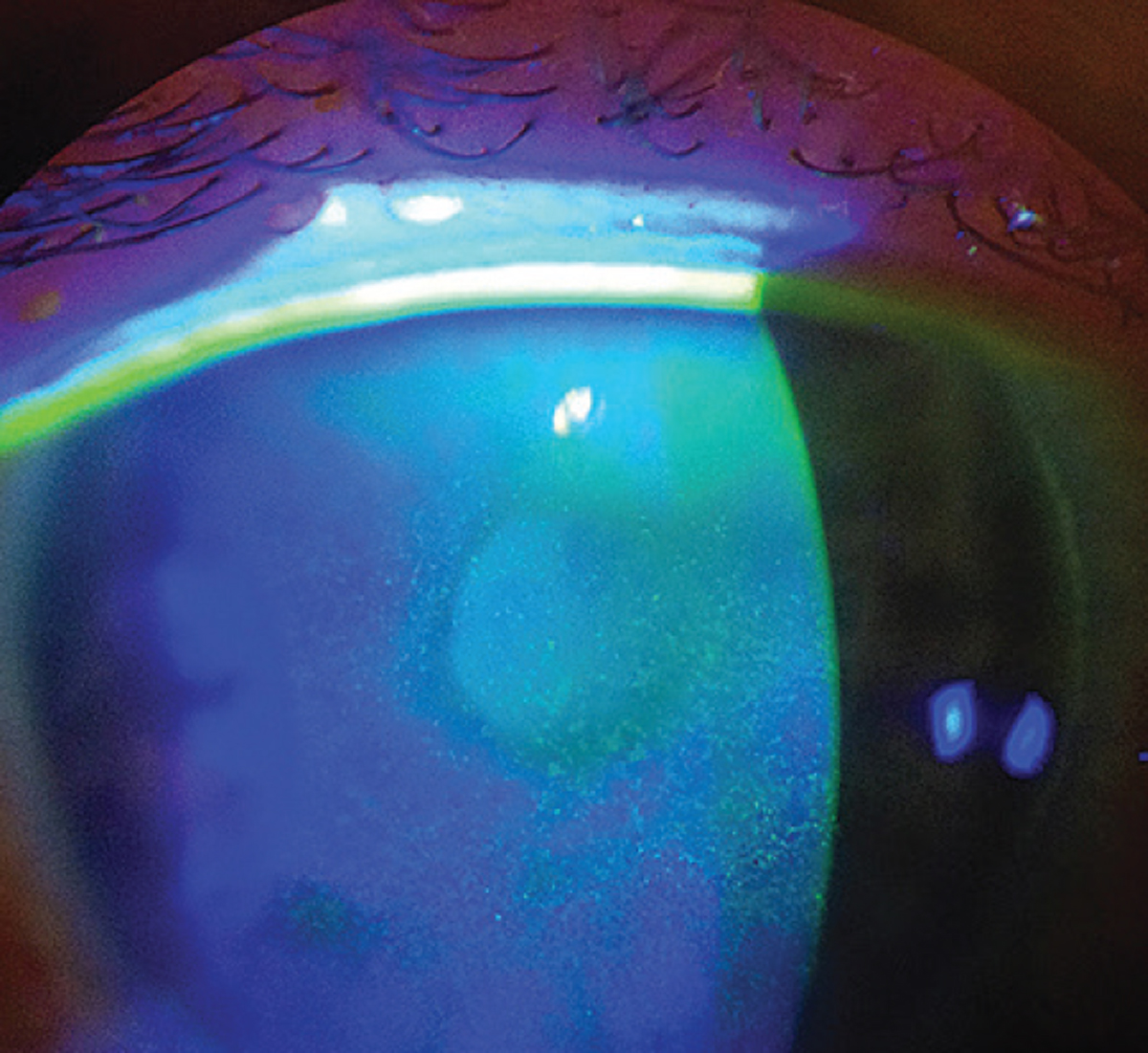

Because signs and symptoms of dry eye don’t always correlate, a clinical exam should always be used to confirm the findings of a questionnaire. Photo: Scott G. Hauswirth, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Busy doctors and distracted patients don’t exactly relish the thought of adding one more step to an optometric visit, but the notion of screening patients for dry eye with a survey tool has merit, experts say. Asking patients to devote a bit of forethought to the state of their ocular surface comfort before their exam can elicit conversations that might not otherwise occur, allowing you to identify some cases that would have gone unaddressed. And when managing a condition as multifactorial as dry eye, keeping a record of when patients feel better or worse helps to identify possible triggers, narrow down the list of potential diagnoses and evaluate response to treatment.

That’s where dry eye questionnaires come in. Since the mid-1980s, when the first symptom survey—the McMonnies questionnaire—was developed, various others have been created and validated as practical screening tools for dry eye disease (DED). This article will explore how to best implement such questionnaires into your practice and walks you through the pros, cons and clinical indications of the various surveys used today to assess this complex condition.

Why and When Should You Use Questionnaires?

When a patient comes to your practice complaining of eye dryness, the actual culprit could be one of many possibilities. Having the ability to know the basic information about the case—such as symptom severity, frequency, pain level and potential triggers—even before the person sits down in your chair is incredibly valuable and can help steer your clinical evaluation in the right direction.

Despite worries that surveys might slow down office flow, “dry eye questionnaires are actually huge time-saving tools,” says dry eye guru Paul Karpecki, OD, of Lexington, KY. “Patients can fill them out online before they come into the office, and the score can be transferred into your electronic medical records. There’s a lot of value in implementing something that doesn’t require staff to administer. That helps increase your efficiencies and diagnostic capabilities.”

In addition to having patients complete the questionnaire beforehand, Dr. Karpecki asks them two questions once they enter the room: what is their worst symptom, and when is it worse? “First, I’ll glance at the score, and if that indicates the patient may have DED, I’ll go through the completed questionnaire and see what it says. Then, I’ll ask those two key questions. Now, I have the information I need to pinpoint which kind of dry eye—or alternative condition—I might be dealing with, and I can go ahead with the examination and diagnosis.”

Another option is to have the patient fill out the questionnaire as they sit in the waiting room, which is what Pam Theriot, OD, of Shreveport, LA, does at her practice. “I can see pros and cons to distributing the survey in either of these ways. If the patient completes it at home, they wouldn’t be able to ask a question or get help if they got stuck on or didn’t understand something. Also, it fills up the time when they would otherwise just be sitting in the waiting room.”

How to Obtain The SurveysWhile most dry eye questionnaires can be used in clinical settings at no cost, there are exceptions. For surveys that are copyrighted, you’ll need to contact a local rep of the company or organization to inquire about how to gain access or rights to distribute the survey at your practice. We have included links on our website to downloadable PDFs of each of the freely available ones mentioned in this article. Some questionnaires offer alternative methods of access. The OSDI can be completed using an app by Allergan called “Dry Eye OSDI Questionnaire.” One catch: it’s currently only available on Apple devices. “Having a patient fill out the survey beforehand on their phone and then having them send or bring in their score could be really efficient,” ICO associate professor Lindsay Sicks, OD, points out. The app could also save time by calculating the scores for you, she adds. “Plus, if you have an iPad at your practice, you could download the app on the device and have the patient fill the survey out that way while they’re in the waiting room. Then, your technician could enter that result right into the EMR,” says Dr. Sicks. Because not every patient owns an Apple device, this may be the more accessible option if you opt to go this route to use the OSDI. For the remainder of the surveys that aren’t app-compatible or accessible to the public via the internet, be sure to reach out to the owner or developer to inquire about usage restrictions. |

Repeating the survey at subsequent visits allows you to quantify how the patient is feeling and responding to treatment. “The biggest benefit of questionnaires is that most of them provide you and the patient with a number that you can use to keep track of what level of improvement is occurring over time,” says Dr. Karpecki. “For example, if a patient scores a 15 on the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED) test, and when they return they score an 8, we know they are at least headed in the right direction.”

Dr. Theriot adds that patients are usually very number-oriented. “Not all of them are, but often they’re very interested in knowing if they’re making progress. I can tell them if they look better, but the questionnaires help them figure out if they feel better.”

Lastly, Dr. Karpecki notes that some patients who wear contact lenses may not provide truthful responses when asked in the exam room to describe their symptoms for fear of having to give up their lenses. “Most patients tend to be more honest about symptoms on a questionnaire, which is less intimidating than face-to-face questioning and can help you address the issue in a way that allows them to also keep their lenses.”

When Aren’t Questionnaires All That Helpful?

Subjective tests can inform doctors on factors of a condition that can’t be observed during a physical exam, such as the level of pain a patient is experiencing or disruption it is causing in their life; however, the tests are not fool-proof, and in some circumstances, the results can be misleading.

For example, take a neurotrophic patient who has been dealing with dry eye for many years and no longer experiences bothersome symptoms due to the gradual downregulation of ocular nerves that has occurred. Though this patient’s questionnaire would likely suggest they don’t have dry eye, they may actually show signs of disease upon examination. Relying heavily on a questionnaire as clinical evidence without factoring in the physical findings would fail to detect disease in some patients such as those with nerve damage, which, according to Dr. Karpecki, happens more often than it should.

“Dry eye is one of the rare diseases where signs and symptoms don’t correlate,” says Dr. Karpecki. “If you look at macular degeneration, the worse the disease, the more vision loss the patient has. In glaucoma, the worse the disease, the more peripheral vision loss that is present. But in some cases of dry eye, as it progresses the patient could actually experience fewer symptoms. For these individuals, having them complete surveys about how their eyes feel doesn’t help us a lot in terms of severity. Most people and researchers think a high score on symptoms equates to more severe dry eye, but many times, low scores can still occur with severe disease.”

|

|

Dry eye surveys can inform you about factors such as frequency and severity of patients’ symptoms, which you wouldn’t know simply by looking at their eyes. Photo: Michelle Hessen, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Theriot also notes that patients with disdain for paperwork who are simply not interested in answering the questions could give untruthful responses and produce a false positive or negative result on the test. Questionnaires that include too many questions could have the same effect and deter honest and thorough completion, which jeopardizes the accuracy of the score. At the same time, as Joseph Shovlin, OD, of Scranton, PA, points out, there may also be a downside to surveys that contain too few questions. “If a busy practice does not allow for lengthy surveys, a discordance between what the clinician feels is important and what the patient is experiencing or trying to convey may allow for patient symptoms to go untreated,” says Dr. Shovlin.

Another point, made by Dr. Sicks, is that sometimes not every item on the questionnaire will apply to each patient. “One question on the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), for instance, asks about driving at night and another asks about using an ATM,” she says. “Not every patient drives and not every patient uses an ATM, so they might answer those questions ‘no, it’s not bothering me any of the time,’ which will pull their score down so that the dry eye looks to be less severe.” It is important to note, however, that most questionnaires, including the OSDI, do offer an “N/A” option for situations like these.

Dr. Sicks adds that this dilemma is commonly seen with younger patients, as most questionnaires tend to have questions geared toward adults. “It’s actually hard to administer these tests for kids, because [using the previous example from the OSDI], they don’t drive at night or work with an ATM. So, is the OSDI really validated for kids? Technically not,” she points out.

Andrew Pucker, OD, PhD—formerly of UAB School of Optometry before a recent move to industry—says that 90% of the patients he sees currently are children and that he personally would choose not to distribute these questionnaires to those under 10 years old. “They usually aren’t able to explain to you what’s going on,” says Dr. Pucker. “Instead, you could ask basic questions about individual symptoms—such as burning, dryness, foreign body sensation, itching, watering—to help you determine a diagnosis.” However, Dr. Pucker notes that in these cases with young patients, you miss out on the value of surveys that allow you to track progression.

In addition, as COVID-19 has dramatically changed many people’s everyday routines, Dr. Sicks notes that “people’s answers to questions about habits or activities might be skewed or different than they were a year or two ago.”

One final consideration of questionnaires is their potential to lead to overdiagnosis of dry eye.

Storing The DataKeeping a dated record of patients’ scores from each dry eye questionnaire can help you detect signs of improvement or symptom progression, as well as determine their response to a certain treatment. No matter how you decide to administer the surveys, whether that be virtually, on paper or face-to-face, you should record at least the patient’s score—or better yet, a scanned image of the entire survey—into your EMR or another data collection system, which may depend on the customization of the EMR at your practice, says Dr. Sicks.“We use a NextGen system and have built a grid specifically for ocular surface disease, which includes a section where you can input the OSDI score and the date, and it keeps track over time,” she notes. “Another way to do it would be to put the survey score in the impression part of your impression and plan.” Whichever method you choose to store the data, be sure that it is easy to access and shown chronologically for easy comparison of scores over time.” |

“It’s important to not get bogged down into thinking that all symptoms that sound like dry eye including those picked up by surveys are truly dry eye, especially when there is no symptomatic relief with seemingly appropriate treatments,” Dr. Shovlin explains. “Suggesting patients have dry eye may be one of our worst mistakes when only a few signs and/or symptoms point in that direction. There are days where everyone coming into the office feels they have ‘dry eyes.’” He notes that when a patient shows no improvement, other differential diagnoses should be considered, such as conjunctivochalasis, environmental irritative conjunctivitis or even ocular misalignment, to name a few.

In any of the cases above, questionnaires may not be as valuable or reliable of a tool in dry eye assessment. Dr. Theriot emphasizes that “you have to rely more on what you’re seeing than on what they’re feeling.” Still, for many patients, questionnaires are a useful tool and can play an important role in clinical decision-making, she says.

How Do You Choose Which Test To Distribute?

There are a number of research-backed tests that can be administered to patients with dry eye. Generally, patients, as well as physicians, want something that takes little time to complete, is easy to understand and will provide them with a numbered score or categorization to gauge the severity of symptoms. To make a good selection for your patients, Dr. Shovlin says that “clinicians have to decide why they find these questionnaires valuable, as well as how to implement these validated tools into their practice in order not to be disruptive to patient flow.”For Dr. Pucker, efficiency is key. “The shorter the survey and the fewer response options, the better,” he says. “For one, people get survey fatigue and really don’t like long surveys.” Secondly, he says, “It’s better to have fewer options—for example, mild, moderate and severe—as opposed to having 10 shades of grey. If you make the options more black and white, you’ll get better responses because mild, moderate or severe responses are slightly less subjective.”

|

|

Depending on how customizable your EMR system is, this may be an ideal place to store patients’ questionnaire scores from each visit. Photo: iStock. Click image to enlarge. |

Selecting a test that asks patients how symptoms are affecting their day-to-day life can give you insight into the severity of the condition and how aggressively to treat it. A recent review of 24 different dry eye questionnaires concluded that the following six address health-related quality of life and were recommended by the study’s researchers for patient evaluation: OSDI, Impact of Dry Eye in Everyday Life, Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score, University of North Carolina Dry Eye Management Scale, Dry Eye-Related Quality of Life and the 25-Item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire.1

The list of questionnaires used in clinical practice settings might look a little different. Below are some of the tests that optometrists use today to assess the growing population of dry eye patients.

Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED)

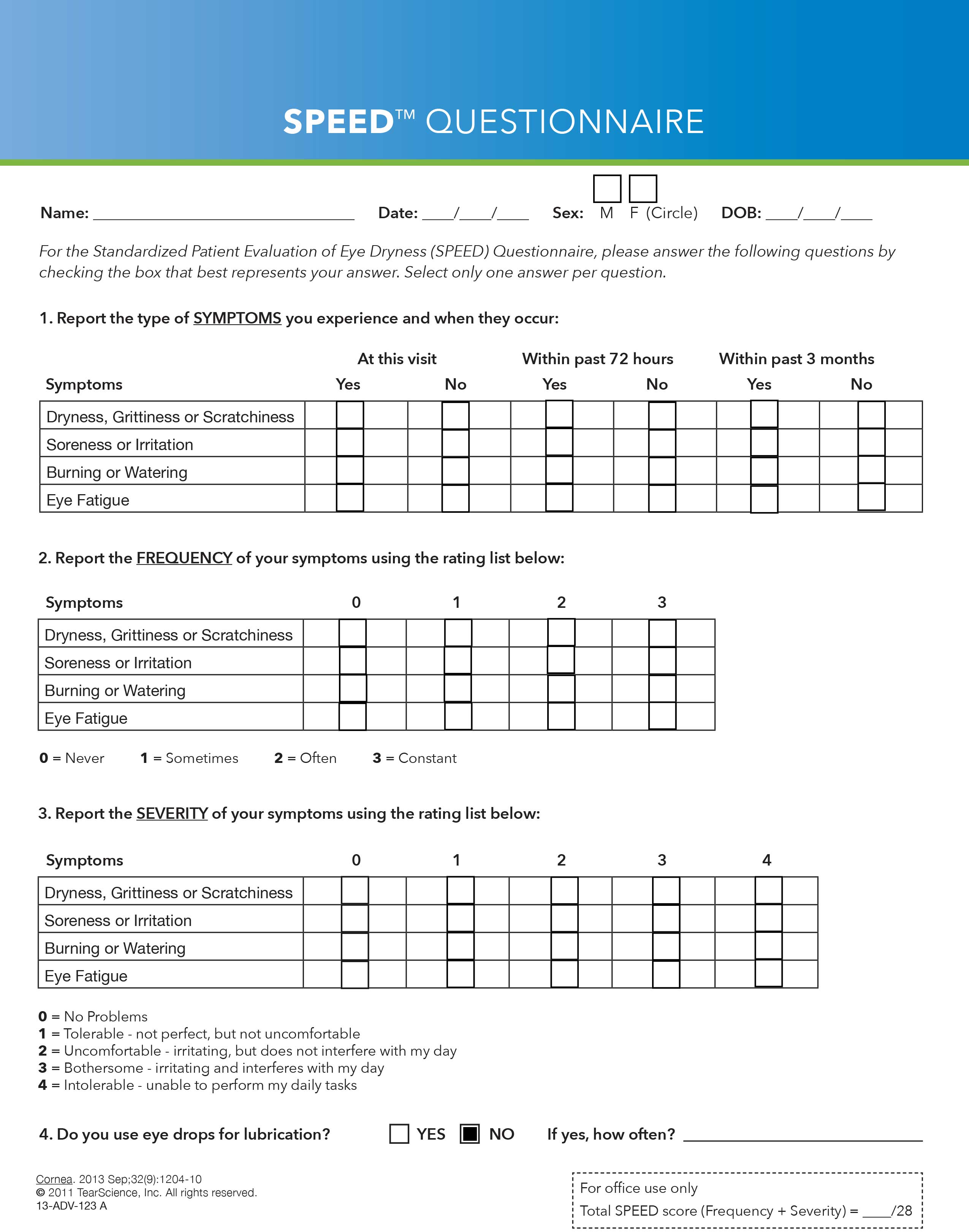

One widely used questionnaire is the SPEED test (developed by TearScience, now a part of Johnson & Johnson Vision), which is brief and easily allows patients and physicians to observe progress or changes in eye dryness and symptoms over time. Divided into four sections, the questionnaire touches on symptom timing, frequency and severity and then provides a numbered score between zero and 28, with zero indicating lack of symptoms.

|

| The SPEED Questionnaire, consisting of four sections, is among the most common surveys used in practice today to assess dry eye. Click image to enlarge. |

The symptoms assessed in the SPEED test include dryness, grittiness, scratchiness, irritation, burning, watering, soreness and eye fatigue.2 The first section asks about the presence of these symptoms and how recently they began, and the second asks about the frequency of the symptoms. The third section asks patients to report the severity of each symptom, and the final section questions patients on whether and how often they use eye drops for lubrication.

A study that looked at the SPEED questionnaire’s ability to detect dry eye found it to be a repeatable and valid instrument for the measurement of symptoms.3 It also determined that the test scores were significantly correlated to ocular surface staining and clinical measures of meibomian gland function, including meibomian gland score and meibomian glands yielding liquid secretion score.3

Dr. Pucker, who participated in a Rasch analysis of the SPEED questionnaire, says the test showed positive results and accuracy in screening for symptoms. “The metrics of the test are good,” he says. “It’s mostly a unidimensional device with meaningful questions that aren’t redundant, so it’s very specific for detecting dry eye.”

Dr. Karpecki explains that on the SPEED test, “anything above a six is considered positive, but really anything over eight is going to be very conclusive for DED.” He notes that for most of his patients, the questions on SPEED offer the information necessary to specify which type of dry eye could be present.

Dr. Theriot says that she distributes the SPEED test to every patient who comes into her office for a dry eye assessment and repeats it every time they come back. She offers two reasons for why she also prefers this test over many of the others.

First, “to have a number to give to the patient at each visit to let them know whether they’re improving,” says Dr. Theriot, and secondly because of its ability to distinguish between the different types of dry eye. It questions patients on more specific symptoms than many other tests, which helps point to the presence of a particular condition. For example, based on her clinical experience, Dr. Theriot suggests that “if a patient reports burning and watering, it’s more likely to indicate evaporative dry eye, whereas if they are experiencing dryness, scratchiness or grittiness, that might indicate aqueous-deficient dry eye,” she says. “If they report eye fatigue, it could be because the patient needs to have an adjustment made to their glasses or contact lens prescription power or has ocular misalignment.”

Download a PDF of the SPEED Questionnaire here.

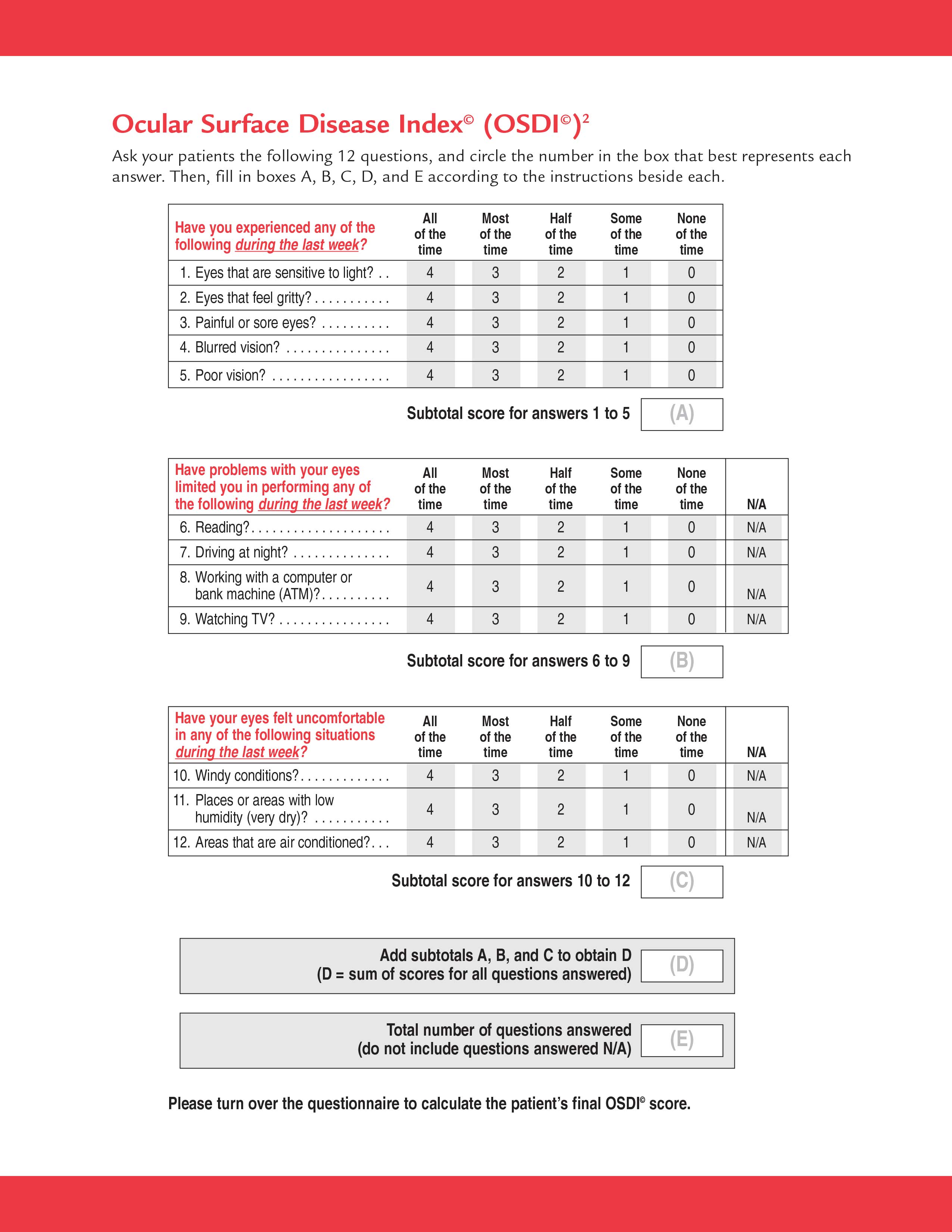

Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI)

Another common survey is the OSDI (Allergan), frequently used as a reliable method of dry eye assessment and quantification in optometric research and clinical trials. The 12-item survey questions respondents on three categories relating to dry eye: ocular symptoms, vision-related function and environmental triggers.2 Patients then rate their responses based on the frequency of the occurrence over the last week from zero to four, with zero indicating “none of the time” and four indicating “all of the time.”

|

|

The OSDI Questionnaire includes items that ask patients about how their dry eye affects daily activities such as reading or using a computer. Click image to enlarge. |

The OSDI produces a quantifiable score between 0 and 100, with higher numbers suggesting more severe disease. A normal score for patients without dry eye would be 12 or below, while a score of 13 to 22 represents mild disease, 23 to 32 represents moderate disease and patients with a score over 33 are characterized as having severe dry eye.2

Studies have shown that OSDI has good specificity (0.83) and moderate sensitivity (0.60) when differentiating between patients with and without DED.2

“The OSDI is very multi-dimensional,” explains Dr. Pucker, who researched the validity of the questionnaire in another analysis. “It tests symptoms, environment and then tasks, so it’s closer to an overall quality of life measurement than many others and screens patients for more than just dry eye,” he notes.

In addition, Dr. Theriot says that along with the SPEED questionnaire, she distributes the OSDI survey at a patient’s first dry eye evaluation. “One of the beautiful things about these questionnaires is that they have been scientifically proven over large patient populations to truly indicate dry eye, but also, in the case of the OSDI, they can give a subset of the severity of the disease,” she says. “That’s why I like to give this questionnaire to patients at the initial exam to be able to gauge where they are on the spectrum of mild, moderate or severe disease.”

Download a PDF of the OSDI here.

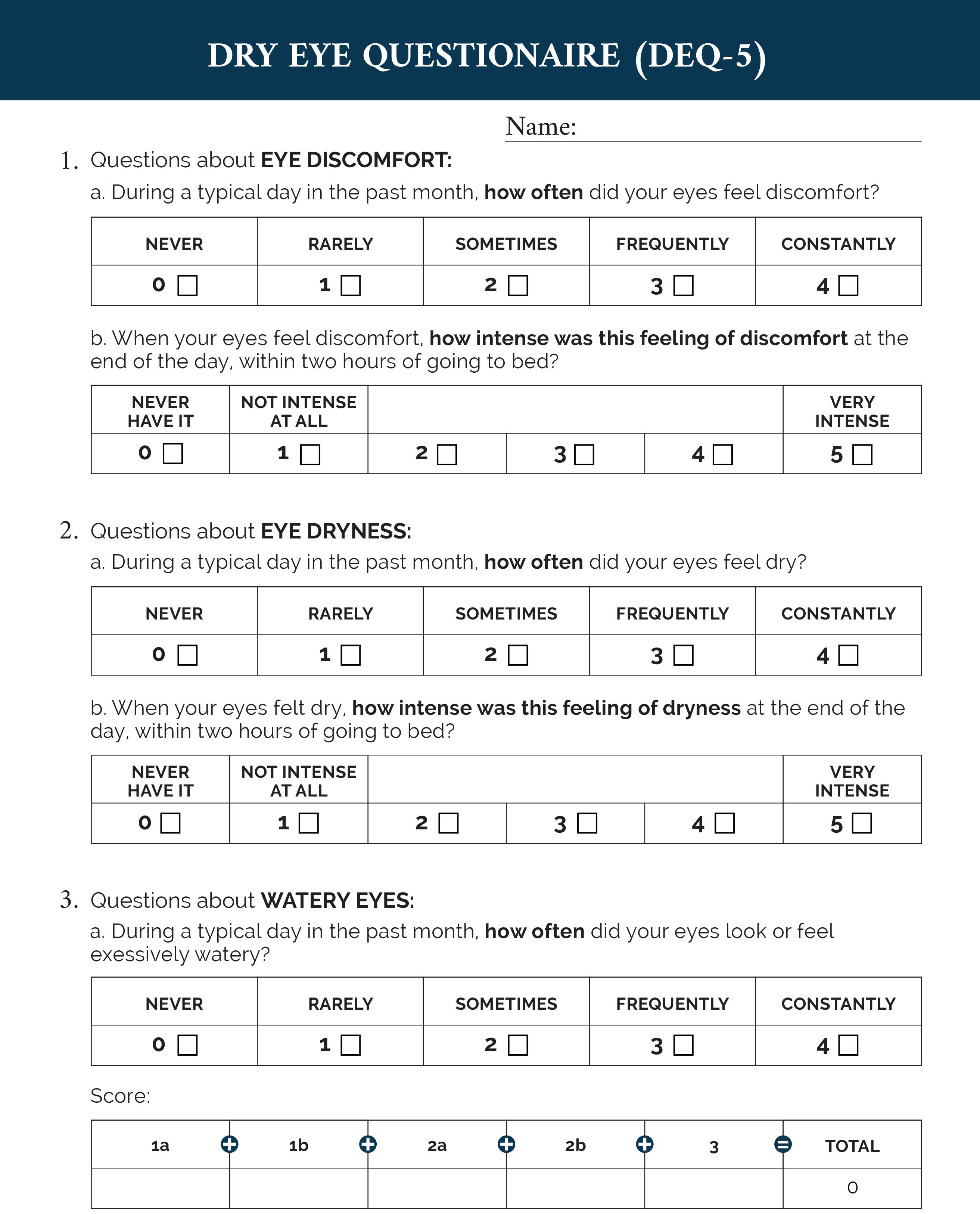

Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5)

A condensed version of the original 21-item DEQ, this one measures symptom severity over the last month. The test contains only five questions, making it one of the quickest to complete and grade. Though it’s much newer and contains half the questions of the OSDI, a recent study comparing the performance of both tests found that the total scores of each were significantly correlated.4 The study reported the reliability of DEQ-5 and OSDI to be 0.92 and 0.82, respectively, and concluded that the DEQ-5 can provide a valid measurement of dry eye symptoms.

|

|

The DEQ-5 Questionnaire is a shorter version of the DEQ, which has long been used as a valid measurement of dry eye symptom frequency and severity. Click image to enlarge. |

The survey asks patients to rate the severity of eye discomfort, dryness and wateriness each from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating “never” and 4 indicating “constantly.” The test-taker is then asked about the intensity of the symptom, with a score of 0 meaning it is not intense at all, and a score of 5 meaning it is very intense. The total score is a number between 0 and 22.

One unique advantage of the DEQ-5 is its ability to differentiate between Sjögren’s syndrome and non-Sjögren’s dry eye. A score above 6 suggests DED and a score ≥12 suggests Sjögren’s syndrome.1

“We use the DEQ-5 on occasion in our practice and have had good success with it,” says Dr. Karpecki. “The reason why we don’t rely on it more is that the SPEED test is just the one we use most routinely and it’s become habitual, but the DEQ-5 is still a great option.”

Download a PDF of the DEQ-5 here.

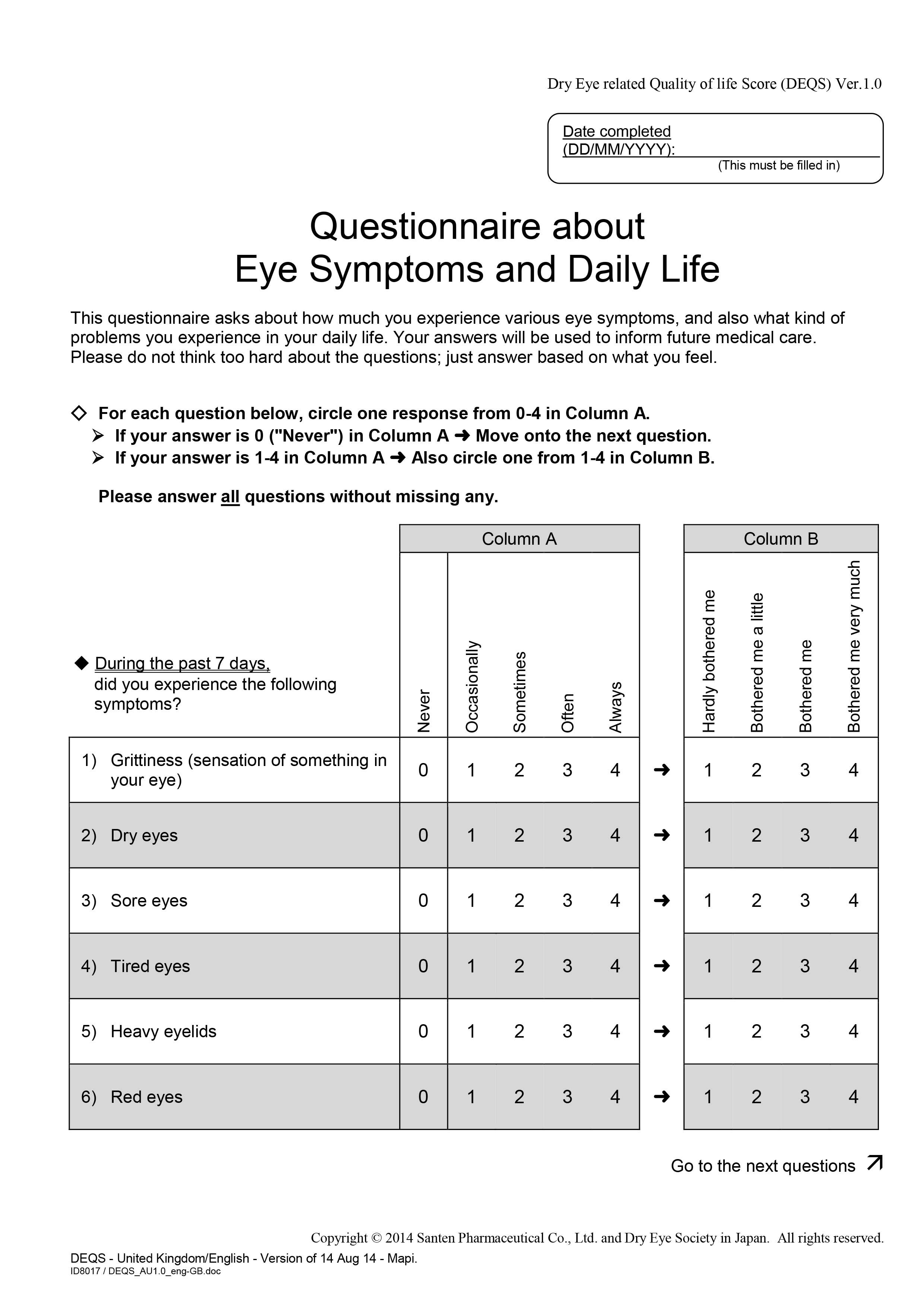

Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score (DEQS)

Originally developed in Japan, the DEQS is one that focuses more specifically on patient quality of life. The survey consists of 15 items and was developed to assess symptoms and their effect on daily living throughout the previous week. It asks patients to rate the

|

|

The DEQS Questionnaire is similar to the DEQ and DEQ-5, although it incorporates more questions about a patient’s quality of life. Click image to enlarge. |

frequency and severity of various ocular symptoms on a scale of 0 to 4 from “not at all” to “always” and “not at all” to “very much.”1

The first six questions focus on ocular symptoms, while the other nine focus on how the patient’s daily life has been affected. It questions patients on things like light sensitivity and difficulty using screens, whether their work is being impacted and whether they are feeling depressed as a result of their symptoms. A quality-of-life score ranging from 0 to 100 is then calculated with the cutoff value for DED being 15 points. A psychometric analysis showed that the test has good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, discriminant validity and responsiveness to change.5

Download a PDF of the DEQS here.

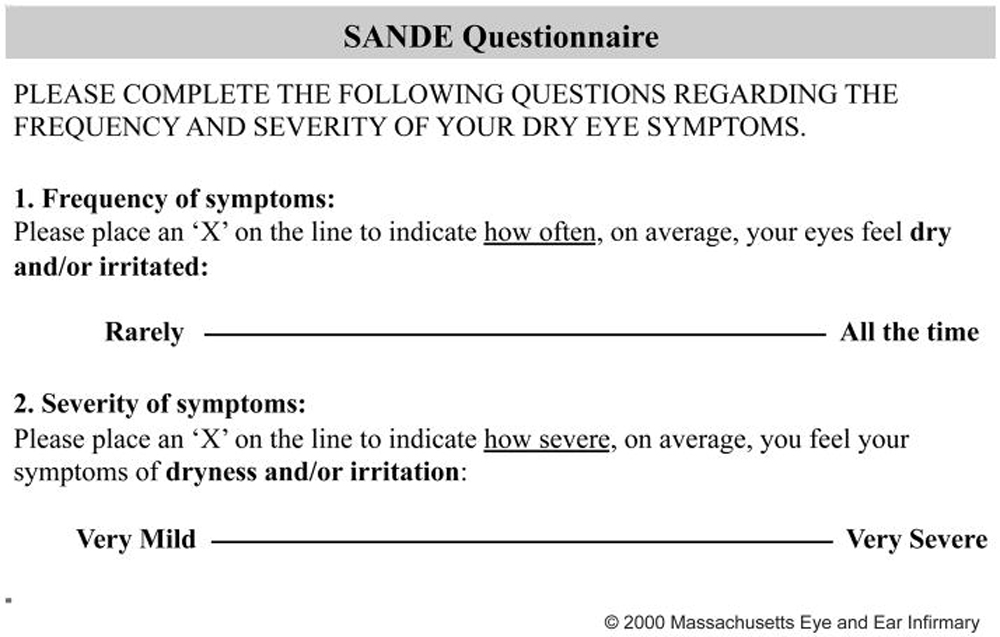

Symptom Assessment Questionnaire in Dry Eye (SANDE)

This is among the shortest of the tests, containing only two questions presented on a visual analog scale. Patients rate the frequency and severity of ocular dryness or irritation by placing an “X” on a line between “rarely/mild” and “all the time/very severe.” In a study that compared this questionnaire with the OSDI, researchers found that SANDE showed a significant correlation and minor differences in scores compared with the OSDI and indicated that the test was short, quick and reliable.6

|

|

With only two questions, the SANDE Questionnaire is one of the most efficient surveys and uses a visual analog scale. Click image to enlarge. |

“Visual analog scales like SANDE are super useful in practice and can help you very effectively see the progression over time,” notes Dr. Pucker. “It’s a very short and simple test that has good metrics, and it’s validated, but I don’t see it used often enough in practice.”

Download a PDF of the SANDE Questionnaire here.

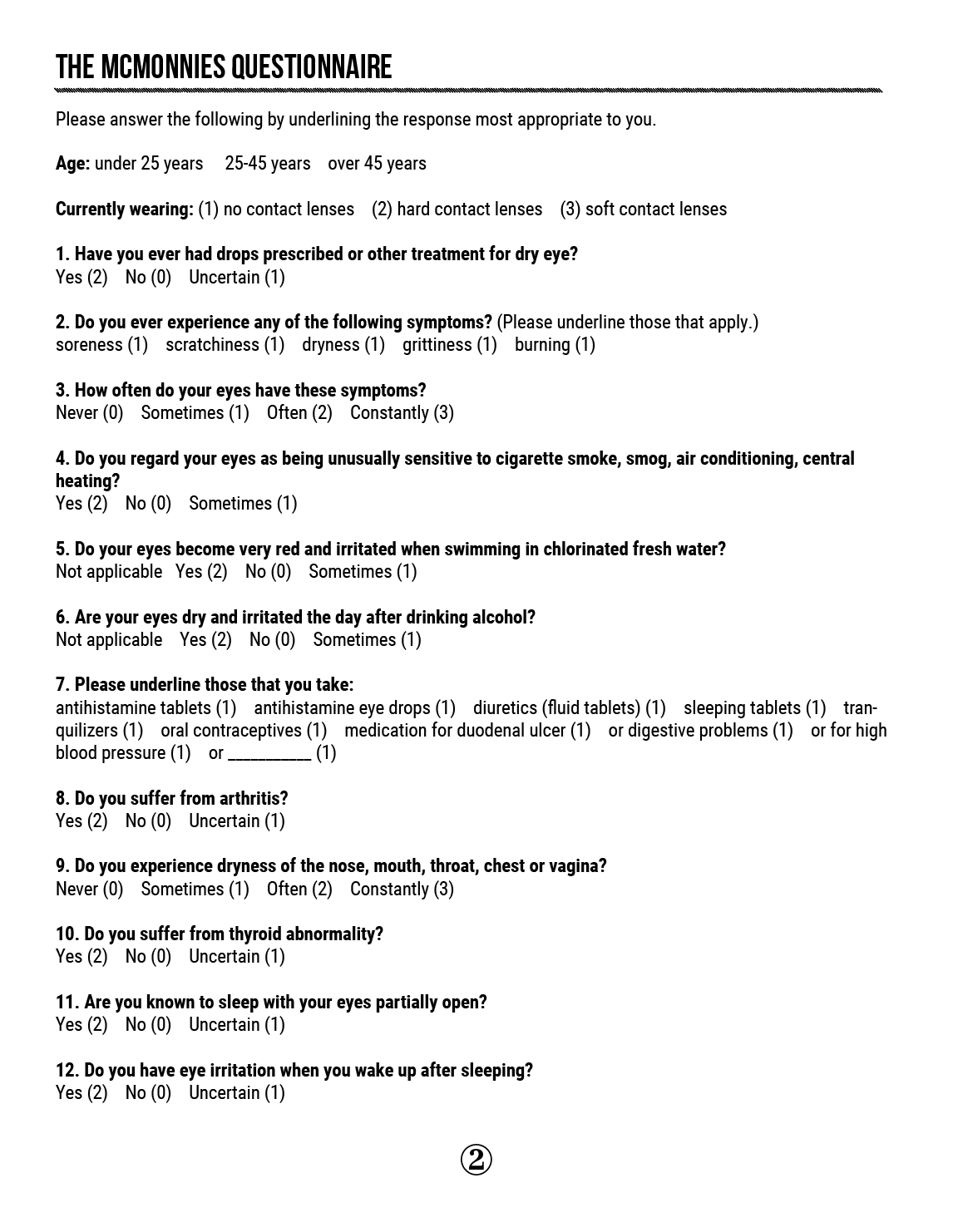

McMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire

Developed in 1986 by Charles McMonnies, this one is among the earliest screening tools for DED. The 12-question test asks patients to describe the frequency and severity of various symptoms, habits and coexisting conditions associated with dry eye by selecting one of several options listed for each item. The results produce a score between 0 and 25, with a score of 14.5 or higher indicating DED.1

|

|

The McMonnies Questionnaire is the oldest of the surveys. It’s also incorporated into the Keratograph 5M. Click image to enlarge. |

Despite having been around the longest, the McMonnies has been shown to have poor internal consistency and inadequately studied validity and reliability.1 Sensitivity of the test has been reported to be between 87% and 98% and specificity between 87% and 97%.7 Authors of a Rasch analysis on the test’s validity had two major concerns. “First, there is no standardized scoring protocol. Second, there is uncertainty about whether the questionnaire can be used to grade disease severity,” they wrote.7 For these reasons, it’s not typically the top choice for use in optometry practices today.

However, in conjunction with other screening tools, this survey can still be useful in patient assessment. Dr. Sicks points out one particular advantage of using this test.

“The McMonnies questionnaire is actually incorporated into the Keratograph 5M,” says Dr. Sicks. “If you have the device, you can run through the entire dry eye analysis. It goes through all of the questions while the patient is sitting there, so you can ask them for their responses face-to-face.”

Download a PDF of the McMonnies Questionnaire here.

|

|

The IDEEL Questionnaire is three pages and 57 questions long. Click image to enlarge. |

Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL)

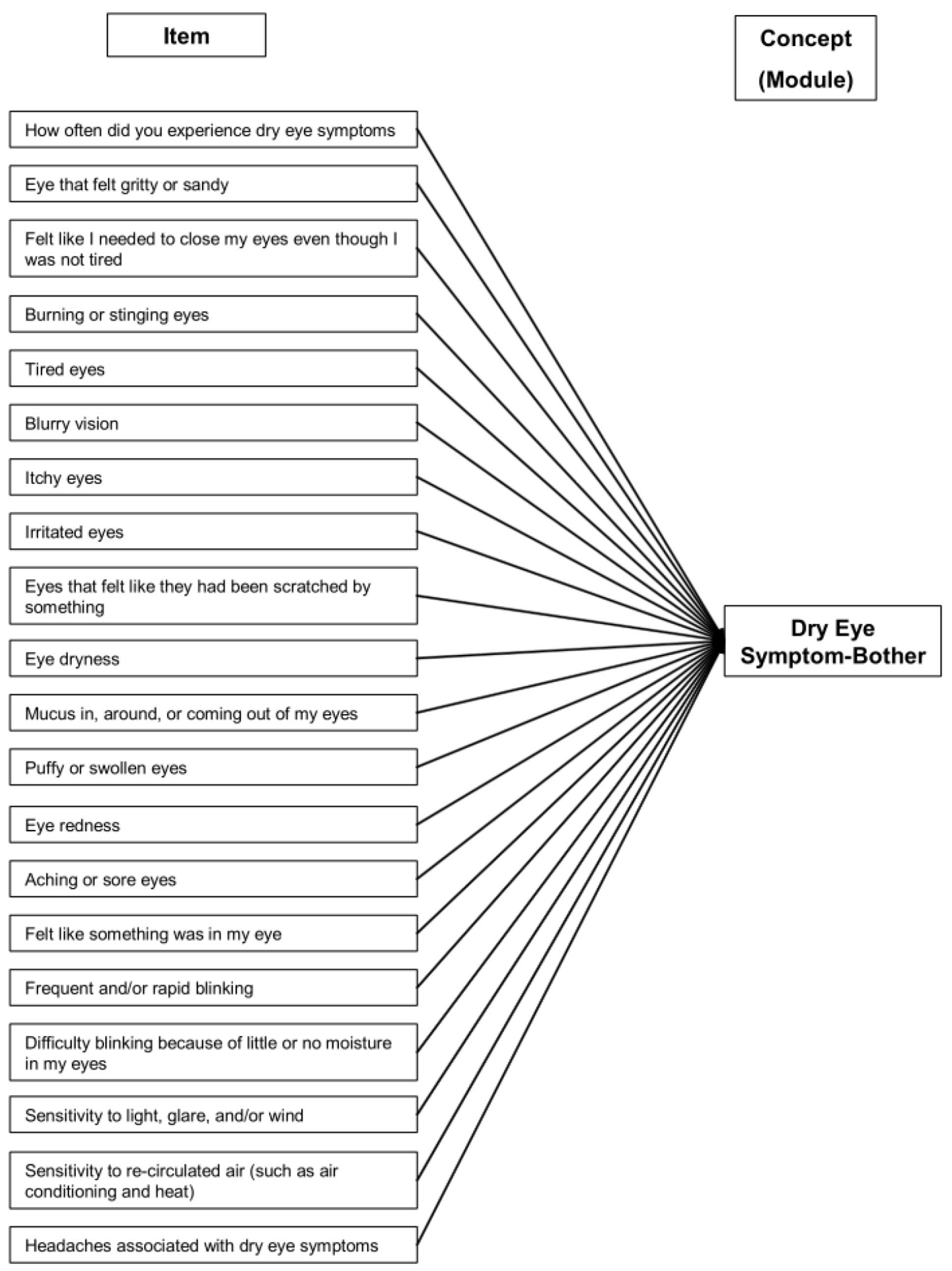

This comprehensive questionnaire, developed by Alcon, includes 57 items and three separate modules, covering questions on dry eye symptoms, impact on daily life and satisfaction with treatment effectiveness and treatment-related inconvenience. Though the test may take longer than others for patients to fill out and physicians to grade, it could offer useful insight into the severity of your patient’s condition, the burden that the disease is placing on them and their satisfaction with the care they are receiving. Results from a psychometric analysis done to develop and validate IDEEL indicated that the test met the criteria for item discriminant validity, internal consistency reliability, test-retest reliability and floor/ceiling effects.8

It’s important to note that in order to distribute this survey to patients in your practice, you will have to purchase it from Alcon with a price tag of a few thousand dollars.

Download a PDF of the IDEEL Questionnaire here.

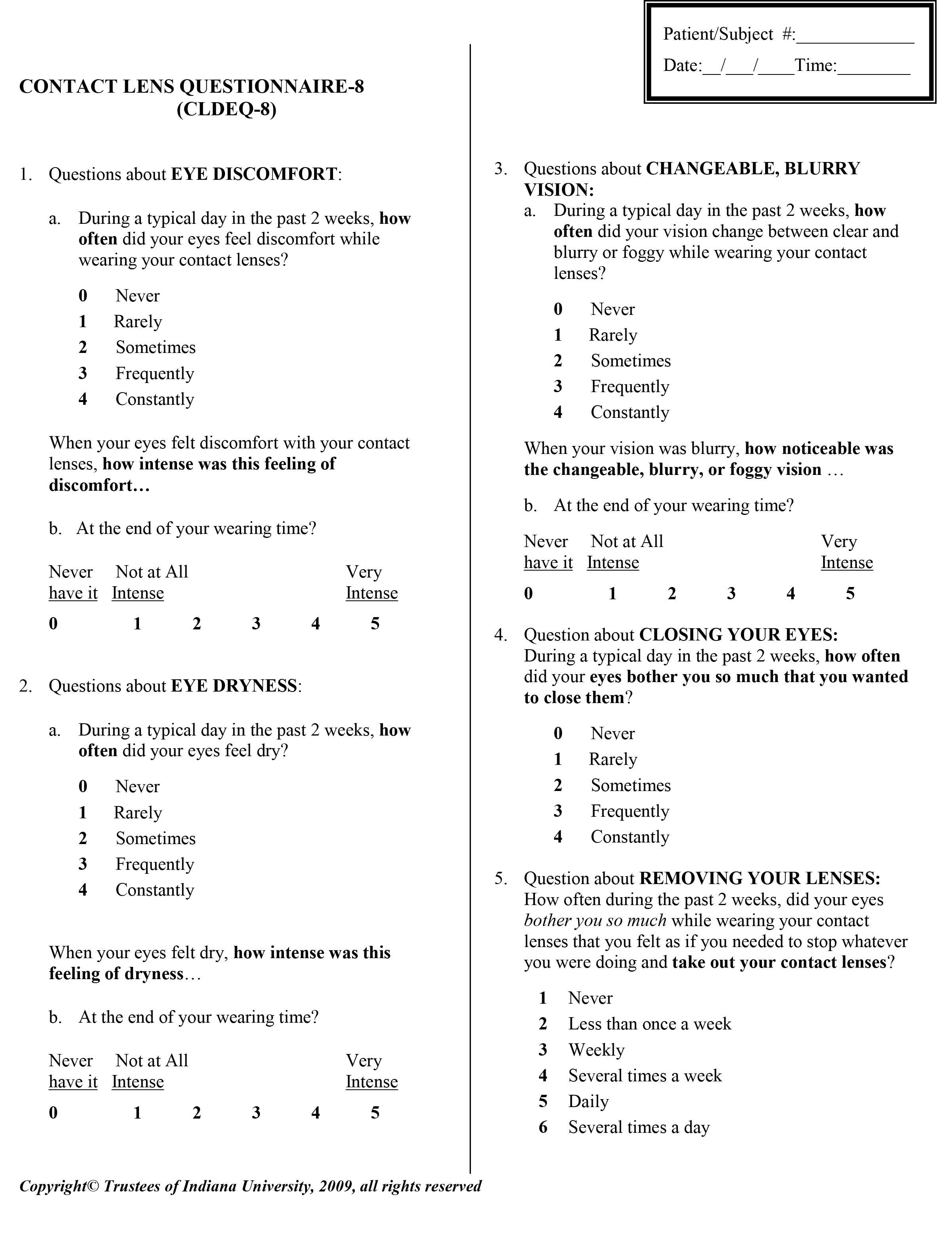

Contact Lens Dry Eye Questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8)

Certain dry eye questionnaires are specifically designed for contact lens wearers, such as the CLDEQ-8. This survey—currently property of Indiana University—includes five questions that ask patients about eye discomfort, eye dryness, changeable or blurry vision and how often the patient has to close their eyes or remove their lenses to relieve the bothersome symptoms.

|

|

CLDEQ-8 is well-suited to assessing dry eye in contact lens wearers. Click image to enlarge. |

“I’ll use the CLDEQ-8 whenever I’m suspecting that a patient is unhappy with their contact lenses so I can quantify how unhappy they are,” says Dr. Pucker. “When it’s a score of 12 or more, that suggests you should make some kind of change, such as in wear schedule, lens material or contact solution.”

A study comparing SPEED with the CLDEQ-8 found that scores of both were associated with self-reported dry eye in contact lens wearers, suggesting that either test could be used to assess this subset of dry eye patients. The SPEED questionnaire was shown to outperform the CLDEQ-8 in one area particularly: the former was able to quantify multiple symptoms while the latter quantified only those of dry eye.9

Download a PDF of the CLDEQ-8 here.

University of North Carolina Dry Eye Management Scale (UNC DEMS)

This single-item questionnaire, copyrighted by the University of North Carolina, asks patients to circle the number between 1 and 10 that best describes how bothersome their dry eye symptoms have been over the previous week. The survey also has an optional section at the bottom where patients can write anything they want the doctor to know about their eyes. Dr. Shovlin says that the UNC DEMS is his first choice if he decides to give a survey to a patient. “It’s very simple, direct and pretty reliable from a severity perspective,” he says.

|

|

The UNC DEMS contains just one question presented along a visual analog scale. |

Download a PDF of the UNC DEMS here.

Takeaways

Dry eye questionnaires can be a very beneficial tool to help you better understand your patient’s condition and how it’s impacting their day-to-day life. It can also increase the efficiency of your practice by allowing you to obtain patient data before the start of the appointment, which leaves more time to ask follow-up questions and perform the clinical exam.

“Although the results of these symptom surveys don’t always correlate to the clinical signs when we’re dealing with dry eye, they can help by offering a starting point and directing to more specific care and assessment of the patient,” says Dr. Sicks. “But you’re still going to have to ask your patients other questions about their specific environment and what’s been bothering them. It’s not the end all be all.”

Dr. Karpecki is the medical director for Keplr Vision and the Dry Eye Institutes of Kentucky and Indiana. He is the Chief Clinical Editor for Review of Optometry and chair of the New Technologies & Treatments conferences. A fixture in optometric clinical education, he consults for a wide array of ophthalmic clients, including ones discussed in this article. Dr. Karpecki’s full list of disclosures can be found here.

Dr. Sicks is an associate professor at ICO and a clinical attending in the Cornea Center for Clinical Excellence at the Illinois Eye Institute. She lectures and conducts research on specialty contact lenses.

Dr. Theriot practices at a multi-specialty eye clinic in Shreveport, LA. Her clinical practice covers a broad spectrum of ocular care with a unique clinical focus on ocular surface disease and dry eye. She is a consultant for Novartis and a key opinion leader for Sun Pharmaceuticals and Kala Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Pucker is currently the senior director of Drug Development at Lexitas Pharma Services. He is also active in clinical practice providing myopia management and contact lens care. Dr. Pucker is a Fellow and Diplomate of the American Academy of Optometry, Fellow of the Scleral Lens Education Society, and Fellow of the British Contact Lens Association.

Dr. Shovlin, a senior optometrist at Northeastern Eye Institute in Scranton, PA, is a fellow and past president of the American Academy of Optometry and a clinical editor of Review of Optometry and Review of Cornea & Contact Lenses. He consults for Kala, Aerie, AbbVie, Novartis, Hubble and Bausch + Lomb and is on the medical advisory panel for Lentechs.

1. Okumura Y, Inomata T, Iwata N, et al. A review of dry eye questionnaires: Measuring patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Aug 5;10(8):559. 2. Eyewiki. Dry eye syndrome questionnaires. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Updated January 14, 2022. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Dry_Eye_Syndrome_questionnaires#:~:text=at%3A%20%5B2%5D-,Standard%20Patient%20Evaluation%20of%20Eye%20Dryness%20Questionnaire%20(SPEED),frequency%20and%20severity%20of%20symptoms. Accessed March 10, 2022. 3. Ngo W, Situ P, Keir N, Korb D, Blackie C, Simpson T. Psychometric properties and validation of the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaire. Cornea. 2013;32(9):1204-10. 4. Akowuah PK, Adjei-Anang J, Nkansah, EK, et al. Comparison of the performance of the Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5) to the Ocular Surface Disease Index in a non-clinical population. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. April 6, 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. 5. Sakane Y, Yamaguchi M, Yokoi N, et al. Development and validation of the Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score questionnaire. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(10):1331-1338. 6. Amparo F, Schaumberg DA, Dana R. Comparison of two questionnaires for dry eye symptom assessment: The Ocular Surface Disease Index and the Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(7):1498-1503. 7. Gothwal VK, Pesudovs K, Wright TA, McMonnies CW. McMonnies questionnaire: Enhancing screening for dry eye syndromes with Rasch analysis. Invest. Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(3):1401-7. 8. Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, Mertzanis P, et al. Development and validation of the Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) questionnaire, a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of the burden of dry eye on patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:11. 9. Pucker AD, Dougherty BE, Jones-Jordan LA, Kwan JT, Kunnen CME, Srinivasan S. Psychometric Analysis of the SPEED Questionnaire and CLDEQ-8. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(8):3307-13. |