|

In nearly 40 years of implanting punctal plugs for dry eye disease (DED) and other ocular surface disorders, attitudes toward the devices have wavered from extreme popularity to widespread rejection. When we last covered punctal occlusion 10 years ago, the literature’s assessment—and our own—was mixed. While we ultimately advocated for the judicious use of punctal plugs, it was predominantly for those patients with moderate to severe DED who did not adequately respond to lubrication therapy and topical immunomodulators, such as Restasis (cyclosporin A 0.05%, Allergan).

We echoed the report of the Dysfunctional Tear Syndrome Study Group, which concluded that “punctal plugs could result in retention of pro-inflammatory tear components on the ocular surface and may enhance damage to the ocular surface, accelerate the disease process, and produce greater patient discomfort,” and to “treat the inflammatory condition before blockage of tear drainage with punctal plugs.”1 Moreover, our opinions reflected those of the most comprehensive assessment of DED and management at that time, the report of the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS).2

As David Sackett, heralded as the father of evidence-based medicine, once famously said: “Half of what you’ll learn in medical school will be shown to be either dead wrong or out of date within five years of your graduation; the trouble is that nobody can tell you which half.” While we like to believe that our formed opinions are spot-on and shatter-resistant, time and additional study often prove us to be incorrect. It can be quite a humbling experience to read your own work years later and realize that you flatly disagree with it.

|

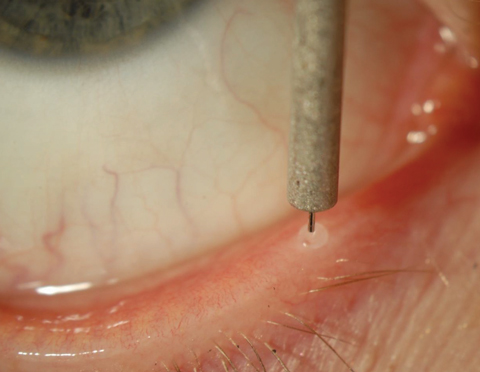

| Punctal plugs like this one can be used in a broader range of patients today than a decade ago. Click image to enlarge. |

New Findings

In the recent TFOS DEWS II report, authors readdressed the issue of inflammation and punctal occlusion. “The use of punctal occlusion in the presence of ocular surface inflammation is controversial because, theoretically, occlusion of tear outflow could prolong the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines on the ocular surface,” it reads. “However, a recent study shows that punctal occlusion in 29 individuals with moderate DED for three weeks resulted in reduced corneal fluorescein staining and symptom scores, without elevation of cytokine or matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels, questioning whether cytokine levels would necessarily elevate with punctal occlusion over short periods of use.”3

The referenced study, in which more than 400 tear proteins were analyzed from subjects with moderate DED, also found that some diagnostic features were predictive of greater success with punctal occlusion.4,5 In general, patients with a lower Schirmer’s test score at baseline were found to have a more beneficial tear protein response than patients with higher scores prior to plug insertion.5

Another recent study also examined subjective and objective measures before and after punctal plug insertion in 45 patients with aqueous-deficient dry eye disease.6 Researchers found that the introduction of punctal plugs resulted in a statistically significant improvement in: (1) mean symptom score (as measured by the Ocular Surface Disease Index); (2) mean tear volume (as measured via the Schirmer’s test); (3) mean fluorescein tear breakup time; (4) pattern of corneal fluorescein staining; (5) corneal sensitivity; and (6) conjunctival impression cytology features.6 There was also a decrease in the dependence on artificial tear use among subjects.6 So clearly, newer evidence suggests that punctal occlusion may provide distinct benefit to patients with DED, both with regard to clinical signs and symptoms as well as tear chemistry composition. The Management and Therapy Subcommittee of TFOS DEWS II stipulated that punctal occlusion may be indicated in “any condition that would benefit from aqueous retention on the ocular surface” (Table 1).3

Table 1. TFOS DEWS II Indications for Punctal Occlusion Therapy3

|

Upgraded Gear

One aspect of punctal occlusion that was really not addressed thoroughly in the DEWS II report was that of plug design and material, particularly with regard to absorbable intracanalicular plugs. The earliest absorbable or “temporary” plugs were composed exclusively of collagen. These can last anywhere from two to 10 days after implantation, depending on the size of the plug and the individual patient.7 Such plugs are ideal for managing temporary surface issues and are useful diagnostically as they help determine whether punctal occlusion and long-term plugs will be well-tolerated.

Long-term absorbable plugs are composed of synthetic polymers that dissolve more slowly than collagen, lasting from two to six months. Materials used in the manufacture of these plugs include glycolic acid/ trimethylene carbonate copolymer, PCL (Δ-caprolactone/L-lactide copolymer) and polydioxanone.7 While many of these products are commercially available in the United States, the peer-reviewed literature is all but devoid of research involving these devices. The primary advantage of this design appears to be the complete lack of cap irritation that may be experienced with silicone punctal plugs. Additionally, since the material dissolves completely over several months, the presumed likelihood of secondary infection and inflammation is low.

Another aspect of punctal occlusion that is often overlooked is the use of perforated punctal plugs, sometimes referred to as “partial occluders” or “flow controllers.” Their design includes an open inner channel that’s 0.2mm to 0.3mm narrower than the shaft width of the plug.8 The primary indication for use of a perforated plug is epiphora, whether encountered after insertion of a conventional plug or associated with acquired punctal stenosis.

Clinical studies show that the use of these devices eliminates epiphora in 84% of patients.9-11 Factors that may limit success include the presence of unmanaged blepharitis and increased patient age, which may be associated with more severe horizontal lid laxity and poor lid-globe apposition.10

Practicing optometrists may still be reluctant to employ punctal plugs for patients with ocular surface disease, except in severe cases where all other treatments have failed. However, our current understanding indicates that this philosophy is outdated. Along with many new and exciting therapies that we have in 2018, tear conservation remains an important step in managing our dry eye patients. Punctal plugs deserve a second chance.

Disclosure: Dr. Kabat is a consultant/advisor for Lacrivera and Ocusoft.

1. Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, et al. Dysfunctional tear syndrome study group. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: A delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea. 2006;25(8):900-7. |