|

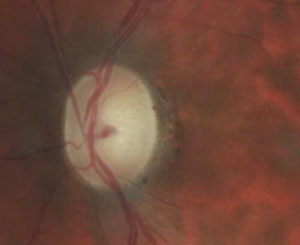

A 56-year-old woman was referred for ongoing glaucoma management. She had been diagnosed with glaucoma in Jamaica five years earlier. She reported progressively worsening vision in her right eye for the past 10 years. Her best-corrected visual acuity was light perception in the right eye and 20/30 in the left. A relative afferent pupil defect was present in the right eye. She ran out of her glaucoma medication and had not instilled the drops for several months. Her intraocular pressure was 19mm Hg OD and 18mm Hg OS. Her central corneal thickness was 560µm and 544µm OD and OS, respectively. She was normal biomicroscopically, and her optic nerves demonstrated significant rim compromise bilaterally. Additionally, the remaining optic rim tissue appeared pale in each eye.

The painless progressive vision loss combined with optic disc pallor concerned us. Was something developing in addition to her glaucoma? Threshold perimetry could not be performed in her right eye due to her poor acuity. However, the results of her left eye showed a dense left vertical visual field defect. She was counseled about the implications of these findings and referred for MRI of the orbits and chiasm, which subsequently revealed a pituitary macroadenoma.

Optometrists are well versed in compressive lesions that impact the visual system. While most ODs are comfortable in recognizing the signs of chiasmal tumors and ordering the appropriate neuroimaging, it is important to understand what comes next for the patient. Once the diagnosis is made, it is incumbent upon the optometrist making the diagnosis to know the current management routine of such tumors so he or she can properly counsel anxious patients.

| |

| A fundus image shows the eye of a 56-year-old woman with glaucoma experiencing progressive visual loss. |

In this column, we review pituitary tumor management.

Presentation

Pituitary adenomas are common intracranial tumors. The prevalence in the general population is about 17%. Many cases are asymptomatic.1 Pituitary tumors demonstrate a peak incidence between the ages of 30 and 60 and are considered rare in individuals younger than 20; women tend to be affected at an earlier age than men.2-4

Patients may present with visual symptoms, including diminished acuity, color desaturation, visual field loss and even diplopia if the cavernous sinus is involved.5 The classic visual field defect is a bi-temporal hemianopia that is denser superior than inferior, although a junctional scotoma with optic nerve involvement and visual acuity loss is also possible. Patients with pituitary adenoma may initially display a normal optic nerve, though long-standing chiasmal compression may lead to optic atrophy and disc pallor.5

Signs and Symptoms

Systemic signs and symptoms can accompany pituitary adenomas. Effects of the expanding neoplasm include headache, seizures or cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea.6 Hormonal changes may also occur. Prolactinomas producing excessive levels of prolactin are the most common form of pituitary adenoma and cause amenorrhea, galactorrhea and infertility in females. Males may experience decreased libido and impotence.6 Tumors that secrete excess growth hormone cause gigantism in children and acromegaly in adults.4,6 Adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH)–secreting adenomas produce Cushing’s disease (hyperadrenalism).4 Despite this array of signs and symptoms, a significant amount of pituitary adenomas are silent and are discovered only by chance during unrelated brain imaging.6,7

Pituitary adenomas are typically benign, slow-growing neoplasms of epithelial origin.8 In most cases, they arise from the adenohypophysis. The optic chiasm is situated approximately 8mm to 13mm above the pituitary gland. Upwardly growing pituitary tumors can impinge on the anterior notch of the chiasm at its lowest lying aspect, producing the classic bitemporal hemianopsia with increased density superiorly. Since tumor growth is usually asymmetrical, the field loss between two eyes is also typically asymmetrical. Pituitary adenomas are differentiated clinically by size and hormonal hypersecretion. Microadenomas are 10mm or less in diameter without sellar enlargement and have little impact on the visual system or gland function and may remain undetected throughout a patient’s life. Macroadenomas are 10mm or larger and have the capacity to expand beyond the sella turcica and induce mass effect symptoms such as headache and visual disturbances.9

When It’s An Emergency

Patients with known or unknown tumors may experience pituitary apoplexy. This is a potentially life-threatening infarcted or hemorrhagic expansion of a pre-existing pituitary adenoma. The accumulation of blood and edema produces a sudden increase in sella turcica contents, compressing vessels and surrounding structures. This often results in acute, severe headache, visual loss, ophthalmoplegia, altered consciousness and potentially life-threatening diencephalic compression and hypopituitarism.

| |

| Our patient’s left eye visual field. We could not perform perimetry in her right eye due to her poor acuity. However, the results of her left eye showed a dense left vertical visual field defect. |

In most cases of pituitary apoplexy, the patient is unaware of the pituitary tumor. It is important to transport a patient with pituitary apoplexy to the emergency room to be stabilized with intravenous fluids and high-dose corticosteroids to replace endogenous hormone deficiency and prevent edema on parasellar structures.

Patients who do not improve will require urgent surgical decompression. Fortunately, patients with pituitary apoplexy who receive treatment fare quite well, with marked improvement in visual and neurological function.10

Treating Pituitary Tumors

Treatment modalities include surgery, radiation and medical therapy. The preferred treatment in any given case depends upon the patient’s age and health—as well as the tumor’s size, invasiveness and degree of hormone production.

Medical therapy is primarily limited to prolactinomas and somatotrophic tumors. Medical therapies include dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine, cabergoline and quinagolide for hyperprolactinemia, while somatostatin analogs such as octreotide and lanreotide, and GH antagonists like pegvisomant, are used for acromegaly. The dopamine agonists, while effective, have substantial adverse effects, including nausea and vomiting, postural hypotension and dizziness, headache, constipation and depressive reactions.2 Long-term use of these drugs is often intolerable.

Surgical Intervention

Pituitary tumors that cause visual effects will most likely be treated surgically, not medically or radiologically. A trans-sphenoidal approach is most often used.9,11 This is an in-patient procedure performed under general anesthesia. An incision is made in the buccal mucosa under the upper lip with blunt submucosal dissection along the nasal septum to the sphenoid sinus. The anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus is opened and the mucosa is removed. The anteroinferior wall of the pituitary fossa is opened and the tumor is removed. The surgical defect is packed with a graft of the patient’s abdominal fat, the anterior wall of the fossa is reconstituted with bone and cartilage and the lip incision is closed.

Recently, surgery has been modified to avoid the need for an incision under the lip or in the front part of the nose. The tumor is reached by making a hole through the back of one nostril into the bottom of the skull. Through this hole, the surgeon can see the bottom of the pituitary gland and the tumor.

The endonasal procedure reduces operating room time by as much as two hours and minimizes the discomfort associated with the surgery, allowing for a quicker recovery compared with older techniques.12,13

Visual improvement following treatment is often dramatic, with the greatest degree of improvement occurring in the first few months.

Our Diagnosis

The patient was told of her diagnosis and likely treatment. Coincidentally, her sister, who accompanied her to the appointment, recognized some of our discussion and relayed that she also had a pituitary tumor and was being treated with bromocriptine. She asked if it would be acceptable to share her medicine with her sister in light of her sister’s new diagnosis. She was emphatically told that such a course was unacceptable and, further, due to the visual compromise, surgery and not medications would be necessary.

The patient was referred for surgery with an understanding of the procedure and prognosis.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jessica Steen for suggesting this month’s topic.

1. Ezzat S, Asa SL, Couldwell WT, et al. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas: A systematic review. Cancer. 2004;101(3):613-9.2. Davis JR, Farrell WE, Clayton RN. Pituitary tumours. Reproduc. 2001;121(3):363-71.

3. Faglia G. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of pituitary adenomas. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1993;129(Suppl 1):S1-S5.

4. Monson JP. The epidemiology of endocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7(1):29-36.

5. Kitthaweesin K, Ployprasith C. Ocular manifestations of suprasellar tumors. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(5):711-5.

6. Chanson P, Salenave S. Diagnosis and treatment of pituitary adenomas. Minerva Endocrinol 2004;29(4):241-75.

7. Chanson P, Young J. Pituitary incidentalomas. Endocrinologist. 2003;13(2):124-35.

8. Minniti G, Esposito V, Piccirilli M, et al. Diagnosis and management of pituitary tumours in the elderly: A review based on personal experience and evidence of literature. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;153(6):723-35.

9. Kaltsas GA, Nomikos P, Kontogeorgos G, et al. Clinical review: Diagnosis and management of pituitary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):3089-99.

10. Murad-Kejbou S, Eggenberger E. Pituitary apoplexy: evaluation, management, and prognosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(6):456-61.

11. Ahmed S, Elsheikh M, Stratton IM, et al. Outcome of transphenoidal surgery for acromegaly and its relationship to surgical experience. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;50(5):561-7.

12. Ishikawa M, Ota Y, Yoshida N, et al. Endonasal ultrasonography-assisted neuroendoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015 Mar 13. [Epub ahead of print].

13. Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, Solari D, et al. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for pituitary adenomas. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(6 Suppl):S3-11.