The statistics on diabetes in the United States are truly staggering—every optometrist is seeing patients with diabetes or those at high risk for the disease on a daily basis. Recent data from the World Health Organization show that at least 422 million people worldwide have diabetes, more than 30 million of whom live in the United States; another 90 million Americans have prediabetes.1 The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) figures show that more than 51% of all American adults had either diabetes or prediabetes in 2012, a figure that jumps to 83% when considering those 65 or older.2

Depending on your patient population, at least half of your patient encounters could include people with abnormal blood glucose levels and those at significant risk for diabetes-related eye disease. Given this reality, we have to start thinking systematically about how we care for and educate our patients who have or are at risk for diabetes. We need to partner with patients, their families, other health care and public health professionals and our communities to reduce diabetes incidence and the complications that come with it.

We need to make diabetes a priority. The task may sound daunting, but every OD can do this with minimal stress by incorporating a few simple strategies.

Step 1: Reduce Risk

The best way to reduce the burden of diabetes-related eye disease is to reduce our patients’ risk of developing diabetes in the first place, or at least delay the diagnosis as long as possible. Before we even dig into the weeds of a clinical exam, we should first focus on those at highest risk, and provide the following evidence-based advice to help reduce their modifiable risk factors (Table 1):3,4

- Get at least 30 minutes of physical activity each day. For those pressed for time, high intensity interval training (HIIT) is a great alternative.

- Eat a plant-centric diet (Paleolithic or Mediterranean-type diet) with a variety of whole fruits and vegetables (12 or more different types per week).

- The single most impactful dietary strategy is to increase fiber to more than 25g each day.

- Consider fasting on alternate days if they’re above ideal body weight and have prediabetes.

- Avoid foods with added sugars, especially high fructose corn syrup.

- Drink water, unsweetened tea or coffee and avoid aspartame (the latter increases insulin resistance by altering the intestinal microbiome).

- Try to get seven to eight hours of sleep every night; turn off all screens at least one hour before sleep to prevent melatonin suppression.

- Get their blood levels of vitamin D tested, with a goal of 40ng/ml to 60ng/ml; if they are below 40ng/ml, take at least 2000 IU additional vitamin D3 daily and retest in three months.

- If you have prediabetes and high blood pressure, ask your physician to take you off of hydrochlorathiazide, a common drug used to treat high blood pressure that worsens insulin sensitivity.

- Reduce consumption of red meat and avoid meat products preserved with sodium nitrate or sodium nitrite (these preservatives are toxic to pancreatic beta cells).

I like giving patients a handout with these lifestyle recommendations so they can ask questions, read and re-read, and so I can highlight the things I think are most important.

|

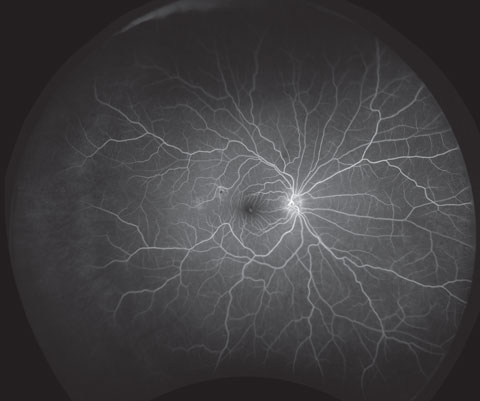

| Screen patients to detect early signs of diabetes-related ocular conditions such as nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, as shown here. Photo: Optos. |

After a patient is diagnosed with diabetes, be cognizant of the factors that increase the risk of eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema (DME), and counsel patients accordingly:5

- Diabetes duration equal to or greater than 10 years (the average patient has had Type 2 diabetes about six years at diagnosis).

- Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) greater than 7.5%, instability of HbA1c, extended periods of poor glucose control.

- Type 1 diabetes, especially during and following puberty.

- Insulin use (insulin promotes VEGF, so higher dose equals higher risk).

- Systemic hypertension (treated/untreated BP greater than 140/85).

- Ocular hypotension.

- Sleep apnea.

- Dyslipidemia.

- Low macular pigment.

- Vitamin D deficiency.

- Latino, African, Native American ancestry.

- Patients of lower socioeconomic status.

- Clinical depression.

Duration and HbA1c are the most important, and I tell my patients that a one-point decrease in HbA1c reduces their risk of retinopathy progression by about 30% based on the evidence. Modifiable risk reduction strategies will continue to benefit patients long after diagnosis of diabetes. In addition, if we know the pros and cons of various diabetes medicines, we better position ourselves to assist patients in treatment conversations with their primary care doctors and endocrinologists (Table 2).

Table 1. Diabetes Risk Factors4 | |

| Modifiable | Non-modifiable |

|

|

Step 2: Prepare Your Exam Lane

You already have many of the tools you need to care for patients with diabetes, such as a slit lamp, fundus lenses, etc., and others are simple additions, such as stocking rapid-acting carbohydrates (glucose tablets, glucose gel packs, single serving boxed orange juice or a few cans of sugar-laden soda) in office in the event a patient experiences acute hypoglycemia while being examined. Here are the other essential tools you will need and likely already have:

- Binocular indirect ophthalmoscope

- Tonometer

- Gonioscopy lens

- Mydriatics

- Sphygmomanometer and stethoscope.

Other extremely helpful tools include a fundus camera to document and compare retinal and optic nerve abnormalities over time, and a spectral-domain optical coherence tomographer (SD-OCT) to help you assess for presence and severity of DME and response to treatment. Ultra-widefield imaging (UWFI) may be especially helpful to identify and document peripheral retinopathy linked to increased risk of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy. A low contrast visual acuity chart, glucose meter and test strips, single-use lancets, sharps container and disposable latex gloves and a rapid HbA1c assay such as the A1cNow Selfcheck from PTS Diagnostics are all helpful to have on hand. Patient handouts on diabetes, diabetic retinopathy, ocular nutrition and science-based supplements can ensure proper education, and provide patients references when they return home. A few online resources, such as a sight-threatening retinopathy risk calculator (www.retinarisk.com) and a BMI calculator (phone apps are great) will also come in handy when counseling patients with diabetes in your office.

|

| UWFI can help spot peripheral retinopathy. |

Finally, a few other “hi-tech” tools may be helpful, such as a macular pigment optical densitometer (e.g. the QuantifEye instrument, ZeaVision) and a device for measuring accumulated glucose metabolites in the crystalline lens (ClearPath DS-120, Freedom Meditech).

Once you have the tools you need, you are ready to conduct an appropriate ocular exam in patients with diabetes.

Dilated eye examinations. These are the gold standard because they allow us to stereoscopically assess the disc and macula and examine the peripheral retina for lesions that increase the risk of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy. Although ultra-widefield imaging is ‘ultra-fantastic,’ it likely will not meet the medicolegal standard of care at the moment.

Don’t forget that diabetes can cause problems beyond the retina, including dry eye disease, cataracts, extraocular muscle paresis and ocular hypertension/glaucoma.

Technology is rapidly evolving, and devices are now available to measure accumulated glucose metabolites—a surrogate marker for diabetes risk—in the crystalline lens. Additionally, low macular pigment is associated with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy, and can be easily measured, monitored and improved via heterochromic flicker photometry. As imaging continues to evolve (e.g., adaptive optics, multi-spectral analysis, fundus flavoprotein autofluorescence), we will be able to detect ocular changes caused by diabetes earlier than ever before, allowing us to better monitor and eventually predict just who will or will not develop sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy, as well as the efficacy of new treatments.

Step 3: Educate Patients

Risk calculators for diabetic retinopathy are great to have in your patient education arsenal. These allow you to immediately show patients that better control of their glucose and BP will help lower their personal risk of needing photocoagulation or injections into the eyes in the future.

It’s helpful to have written materials that explain diabetic eye disease. These can complement your recommendations for follow-up, especially when caring for patients with pre-existing retinopathy and double-especially for those requiring or undergoing treatment by a retinal specialist. It is important for ODs to know that metabolic goals for patients with diabetes (i.e., HbA1c, BP, lipids) are supposed to be individualized based on life expectancy, cognition, comorbidities and complications. For instance, an HbA1c goal of 8% or less may be reasonable for an 80-year-old with little or no retinopathy, heart disease or impaired cognition.

Table 2. Clinical Pearls for Diabetes Medicines6,7

|

In my experience, patients generally don’t respond well to fear until eyesight has been lost, so I endeavor to be an advocate, not a critic. If I do criticize something, I let patients know I am criticizing a behavior, not them. After counseling patients on what we can do in concert with other members of the health care team to reduce the risk of vision loss, I ask patients what they would like to improve before the next eye examination. Be sure to ask for specificity. For example, “I want to get my HbA1c under 8%,” “I want to lose 20 pounds,” “I want to walk 8,000 steps every day,” I put their goals in the chart ask them to write them down while their eyes are dilating and tell them we’re going to assess their progress at follow up—it’s all about memory, buy-in and accountability. I also ask my patients with diabetes if they would like to involve family members in these discussions, because good diabetes control and self-management often require support from loved ones. This also reinforces strategies for preventing diabetes in at-risk family members and builds my practice.

Step 4: Build Your Practice

With more than 30 million patients with diabetes in need of care, catering to this patient population will undoubtedly help your practice grow.1 The first step to increasing your patient base is simply telling patients and their family members that you have a special interest in diabetes and preventing associated vision loss.

Additionally, inform every health care provider whom you see as a patient or who is already your patient about your interest in and focus on diabetes. The interdisciplinary Pharmacy/Podiatry/Optometry/Dentistry model endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control is an important tool, and one you should become familiar with and ask other providers to follow.8Comanagement is key for these patients, so send a timely (within two weeks) diabetes eye examination report to the primary care provider every time you see a patient with diabetes, even when there are no significant findings; be concise, compare current findings with previous findings (e.g., “our patient has mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy without macular edema, and this appears stable compared to my last examination”), don’t use abbreviations with which other providers have limited familiarity (e.g. OU, NPDR, DME) and don’t forget to be complimentary to providers who are doing a great job.

|

| A macular pigment optical densitometer is a high-tech, optional tool to add to your exam arsenal. |

To ensure patients have access to the right information from everyone in your practice, teach your staff about diabetes and its ocular effects. Armed with the right education, they can reinforce your commitment when patients and potential patients call your office for an appointment.

We all are going to see more patients in our practices who have diabetes or are at risk for the condition. The so-called ‘gray tsunami’ guarantees increased prevalence of both diabetes and diabetes-related eye disease, despite recent reductions in incidence.2 This gives all of us a chance to make a difference in public health by collaborating with patients and other stakeholders to make diabetes a priority, consistent with recommendations made in the recent report by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (formerly the US Institutes of Medicine) to realize the “potential for public and private collaborations at the community, state and national levels to elevate vision and eye health as a public health issue.”9 If we strive to increase our knowledge of diabetes, proactively educate our patients and our communities about diabetes and eye disease and communicate clearly with other diabetes care providers about what we have to offer, each and every one of us can create a growing diabetes specialty niche within our optometric practices.

|

1. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet. 2016 Apr 9;387(10027):1513-30. 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Annual number (in thousands) of new cases of diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 18-79 years, United States, 1980-2014. National Health Interview Survey. Available at www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/incidence/fig1.htm. Accessed September 19, 2016. 3. Khavandi K, Amer H, Ibrahim B, Brownrigg J. Strategies for preventing type 2 diabetes: an update for clinicians. Therapeutic Advances in Chron Dis. 2013;4(5):242-61. 4. Ley SH, Ardisson Korat AV, Sun Q, et al. Contribution of the nurses’ health studies to uncovering risk factors for type 2 diabetes: diet, lifestyle, biomarkers, and genetics. American J Pub Health. 2016;106(9):1624-30. 5. Lee R, Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema and related vision loss. Eye and Vision. 2015;2:17. 6. Triggle CR, Ding H. Cardiovascular impact of drugs used in the treatment of diabetes. Therapeutic Advances Chron Dis. 2014;5(6);245-68. 7. Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: A scientific statement from the american heart association and the american diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(9):1777-1803. 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Working together to manage diabetes: A toolkit for pharmacy, podiatry, optometry, and dentistry (PPOD). Available at www.cdc.gov/diabetes/ndep/toolkits/ppod.html. Accessed October 20, 2016. 9. US National Academies of Sciences Health & Engineering 2016. Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health. Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow. Available at www.nap.edu/read/23471/chapter/1. Accessed September 18, 2016. |