Who is Your Patient?This series explores how both innate and acquired elements of identity manifest in the clinic:

|

Neurodevelopmental conditions are defined as chronic mental or physical impairments that occur at conception or shortly after birth. These impairments continue indefinitely, and individuals can present with varying functional abilities. Early identification and intervention are important to offering individuals who are differently abled the best opportunity to develop to their fullest potential.

Optometrists play an important role in these patients’ care. Epidemiological information tells us that visually handicapping conditions such as strabismus and amblyopia are prevalent in this population.1-5 Therefore, early and comprehensive vision care is vital.

While the need for comprehensive eye care is great in these patients, optometrists who feel comfortable evaluating them are rare. However, with a few easy and simple modifications to our schedules, examination techniques and communication styles, some of the apprehension can be eased. This article offers some clinical pearls and tips for those wanting to incorporate this much-needed service into their practices.

A Welcome Start

Providing vital optometric care is paramount and can be done even in busy offices with easy adjustments. Scheduling patients with special needs can be challenging in a busy practice setting when large groups of people can make some individuals uncomfortable. To best address this concern and still see these patients, ask your staff to set the clinic’s expectations about what to expect in your office so the patient can be prepared. Offer a separate waiting area if this is at all possible.

Also, when scheduling these patients, have the scheduler ask the caregiver if there is a time of day that is best for the patient to be seen. Try to accommodate this request so that the patient is more likely to respond well to testing.

|

| Signs that a patient is comfortable include relaxed posture, smiling or engaging in any type of friendly interaction with the optometrist. |

Once the patient arrives, try to limit the amount of time they must wait in the reception area prior to the exam. Limit pre-testing with the technician, such as automated visual fields and retinal photos, as these are often techniques that offer limited data and stress the patient.

In the exam room, eliminate clutter on counter tops and remove distractions such as equipment or objects within reach of the patient as these can be detrimental to the patient’s ability to respond.

Carefully consider the best positioning for each individual patient. This can include leaving the patient in a comfortable wheelchair and having the patient sit on the caregiver’s lap or laying on a mat on the floor. Choose the position that will allow the patient to be most comfortable and allow them to respond to testing without expending muscle energy to hold up their head or sit upright if this is difficult for them.

|

| Use a 20D lens and transilluminator for an ocular health evaluation. |

Remember that first and foremost patients with special needs are people. Don’t define these patients by their condition. When communicating, use people-first language: “a child with autism,” not “an autistic child” or, worse, “an autistic.”6 Never put the diagnosis before the person. Always address case history questions with the patient first and allow them to answer as they are able. The caregiver can fill in the blanks. To the extent possible, have your office staff collect as much case history as possible prior to the patient arriving at the office. This can be done though a web-based secure history form or over the phone once confirmation of the caregiver’s identity is established.

Extended case history during the exam can cause anxiety for the patient, so keep this brief. During the exam, speak in short, declarative sentences and visually support what you say with pointing. Match your facial expressions to your words and avoid speaking loudly, using sarcasm or repeating instructions over and over. Often, there is a delay in auditory processing; count to five before you repeat yourself as your patient is likely to respond during that time once they have completed processing your instruction.

Adjust Your Technique

Techniques to gain the patient’s cooperation during the exam are important. Offering choices allows the patient to decide to participate. Would the patient like to watch Elmo or Mickey Mouse while retinoscopy is being done? Talking your way through the exam also helps. Explain what is going to happen and help the patient anticipate a transition to the next task by giving them forewarning. Let them know you have one more minute with this activity and then you will do something else.

Ask the caregiver for best practices when working with a patient to motivate them and make them feel comfortable. Does this patient respond well to clapping after a task is successfully completed? Are they motived by stickers or food?

|

| Consider the best positioning for each patient, such as leaving them in a comfortable wheelchair. Choose the position that will allow them to respond to testing without expending muscle energy to hold up their head or sit upright if this is difficult for them. |

Have the caregiver share the techniques they use with the patient to best motivate this individual. The caregiver can also give the optometrist insight into whether the patient uses sign language to communicate and can show you a few signs that will help throughout the exam. Singing songs during the exam and playing the patient’s favorite music or video on a phone or tablet can also help improve cooperation.

Many patients with special needs have sensory issues, such as tactile defensiveness, or an aversion to touch or being touched. Be considerate of this and inform the patient of the need to touch them prior to performing a technique that requires touch or holding an object near the patient’s face, such as during a cover test, lens rack retinoscopy or binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO). Demonstrate the technique with the caregiver or a stuffed animal to help acclimate the patient. Start by touching the patient away from their face and slowly work up to there.

Recognize that behavior is communication. If the patient is becoming tense or beginning to perform self-stimulating behaviors, allow the them to take a break. Stimulation of large muscle groups is calming, and you can have the patient take a moment to stretch or walk around the room, if they are able. Additionally, ask the caregiver if the patient can have a snack or bottle as way of a break during the exam. A weighted blanket can calm a patient who is upset.

Establish a rapport with the patient to make them feel comfortable with the optometric exam and with you. Watch for signs that the patient is comfortable such as relaxed posture, smiling or engaging in any type of friendly interaction with the optometrist. Have a battery of different lighted toys and high contrast toys, i.e., black and white. Employ the “one toy, one look strategy” when deciding on the number of toys that you will need. If the patient has seen it, grab a new toy to hold their interest.

Begin the exam with versions, gross visual fields and near point of convergence prior to visual acuities to help the patient become comfortable. These allow optometrists to make initial observations about the patient’s overall visual functioning that will help guide the rest of the examination. The gestalt of the overall visual function will be developed once the examination is complete.

Testing should be done to the highest level possible, i.e., using as close to standard techniques as the patient can handle and moving down the level of complexity as needed to meet the needs of the individual patient.

|

| Be open to using forced choice or preferential looking types of visual acuity testing if the patient cannot perform Snellen acuity. |

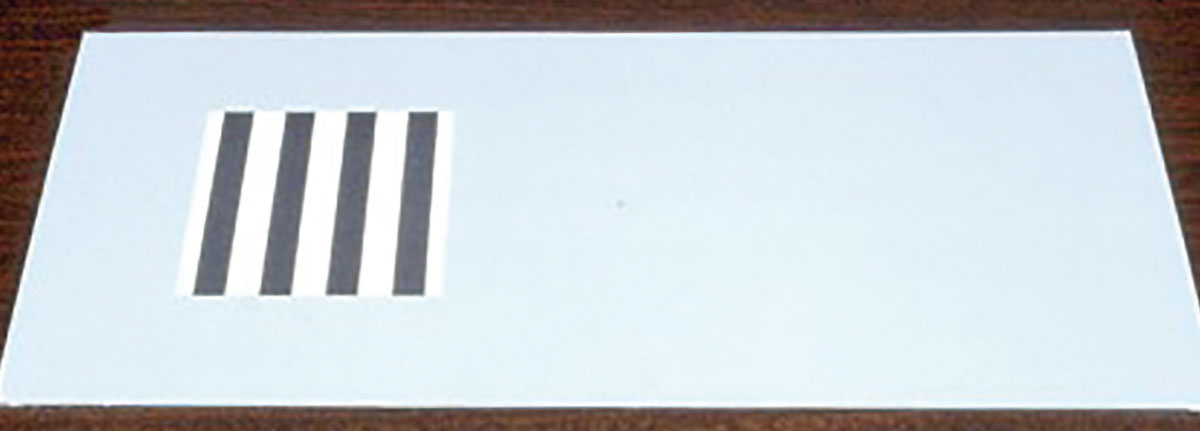

The exam will often be primarily comprised of objective testing. Clinicians will need to be open to using forced choice or preferential looking types of visual acuity testing if the patient cannot perform Snellen acuity, cycloplegic retinoscopy using lens bars, and use a 20D lens and transilluminator for an ocular health evaluation.4 Use your observational skills, ability to adapt testing to meet the developmental needs of the patient and your knowledge of what to expect for the patient’s particular condition to fill in the data. Limit testing to those data points that provide the most bang for your buck, i.e., look for any amblyogenic factors or treatable disease first and foremost.

|

| Don’t rush, but be efficient. Set a goal of limiting data collection to a total of 30 minutes in the chair at the most. Also make sure to be considerate and inform the patient of the need to touch them before performing a technique that requires contact. |

The evaluation of a patient with special needs should be efficient: get in, get it done, get out. Set a goal of limiting data collection to a total of 30 minutes in the chair at the most.

Perhaps more than any other population, working with patients with special needs brings with it some unique psychological challenges. This includes understanding where patients stand with medical procedures they have previously had to endure. One thing that can cause anxiety in these patients is the white coat. Do not wear one when seeing this population.

Other common triggers of anxiety include unexpected or explained procedures and, of course, drop installation. To help with the anxiety of drop installation, be sure to make it quick with limited or no prior discussion. Ask the caregiver to help hold the patient and have an extremely interesting toy to distract the patient once the drops are instilled. Once the drops are instilled, allow the patient to exit the exam room and take a break, have a snack or some other soothing experience.

Let the caregiver know that less patient response is required for the subsequent techniques (retinoscopy and BIO) and that very young patients can actually be asleep during the completion of the examination.

To triage these patients, be familiar with common eye conditions associated with the patient’s specific neurodevelopmental condition to help prioritize the most important aspects of the optometric examination.2,3

Resources and Care Team

Optometrists are uniquely able to provide resources for families of patients with special needs. Because vision plays a primary role in learning, the link between optometric services and education is strong. Parents of children with special needs must learn to advocate for their children and navigate what can be a confusing educational system, so offer them resources that could help before they leave your office.

Answering The “Three Questions”During their lecture, “Pediatric Special Populations for the Primary Care Optometrist,” at the AAO 2021 Meeting in Boston, Jenelle Mallios, OD, and Matthew Vaughn, OD, relayed to attendees three questions that helps treat this population: 1. Can the child see? Is there significant refractive error affecting their visual demands? 2. Are the eyes aligned? Are there binocular issues affecting their visual demands? 3. Are the eyes healthy? “If you answer these three questions to the best of your ability, you did your job,” Dr. Vaughn asserted. “You may feel like you didn’t do much, but this is likely the most that anyone has done concerning eye care for these children.” |

Providing information and support can not only help the family but can also connect the optometrist to the educational system and build their practice. Contact the schools in your local area and introduce yourself to make them aware that you offer this service in your practice.

An interdisciplinary approach is necessary to success. Working as a team with the patient, parents, educators and other professionals involved in the care of a patient allows the optometrist to provide their input towards collaborative and comprehensive care and support.

|

| Retinoscopy lens racks are useful for young children who are unable to sit behind the phoropter. |

Have a list of resources in the office, such as brochures with information about parent support groups or local schools that provide additional services for patients with neurodevelopmental conditions. Provide the contact information for other professionals who see children with special needs in your area, such as occupational therapists for patients needing sensory, feeding or gross/fine motor treatment, physical therapists for patients needing muscular/skeletal intervention, speech pathologists who can provide communication devices or speech development services or psychologists who can provide overall support to the patient and the family.

Each professional can provide rehabilitative care for patients with neurodevelopmental conditions. If vision is not the primary or only concern, making referrals to the appropriate professional allows the optometrist to provide comprehensive care as well as build their network of providers who can become a referral source for the optometrist as well.

Providing the family and other professionals with a summary of your findings and recommendations as well as your referrals should be part of the plan of care when providing holistic rehabilitation for these patients.

Be sure to define the optometric jargon in your reports using laymen’s terms and include visual acuity, refractive status, ocular health and all recommendations including, but not limited to, spectacle wear schedule, patching schedule, classroom accommodations and activities to improve visual function.

Takeaways

The visual needs of patients with neurodevelopmental conditions are prevalent at rates above those of the unaffected population and can be severe. Providing early, comprehensive, interdisciplinary care for these patients is important to improve these patients’ quality of life.

Optometrists who are able to provide this care also enjoy the professional fulfillment of collaborating with like-minded professionals in their communities to care for this underserved population.

Dr. Heyman is the assistant dean of student affairs and an associate professor at Marshall B. Ketchum University’s Southern California College of Optometry. She is the coordinator of the vision program at Beyond Blindness in Santa Ana and coordinates the Special Populations/Pediatric Visual Impairment Service at the University Eye Center at Ketchum Health. She has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Salt A, Sargent J. Common visual problems in children with disability. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(12):1163-8. 2. Chang MY, Gandhi N, O’Hara M. Ophthalmologic disorders and risk factors in children with autism spectrum disorder. J AAPOS. 2019;23(6):e1-337.e6. 3. Dufresne D, Dagenais L, Shevell MI, REPACQ Consortium. Spectrum of visual disorders in a population-based cerebral palsy cohort. Pediatr Neurol 2014;50(4):324-8. 4. Purpura G, Bacci GM, Bargagna S, et al. Visual assessment in Down Syndrome: the relevance of early visual functions. Early Hum Dev. 2019;131:21-8. 5. Williams C, Northstone K, Borwick C, et al. How to help children with neurodevelopmental and visual problems: a scoping review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(1):6-12. 6. Crocker AF, Smith SN. Person-first language: are we practicing what we preach?. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:125-9. |