25th Annual Dry Eye ReportThe most commonly encountered ocular condition enters the spotlight this month. Inside the May 2024 issue of Review of Optometry, get the scoop on omega fatty acids for dry eye, learn how to match dry eye patients to treatments and find a step-by-step guide to managing OSD. Check out the other dry eye-themed articles featured in this issue:

|

Treating patients with dry eye is hardly ever straightforward, given the condition’s widely varying presentations and lengthy list of potential causes. Even once you pin down the root cause of a patient’s ocular surface disease, a second challenge awaits: deciding on a treatment approach that will effectively target their unique set of signs and symptoms. While it’s certainly positive that a wide range of pharmaceuticals and in-office procedures is available today, clinicians must be able to use patients’ clinical data to match them with the most appropriate intervention.

Here, we will present several clinical scenarios involving patients with various forms of dry eye, from the most common and obvious to the more rare and insidious. For each case, we'll discuss the workup and treatment options, as well as share how we would proceed.

Case 1: Garden Variety Dry Eye

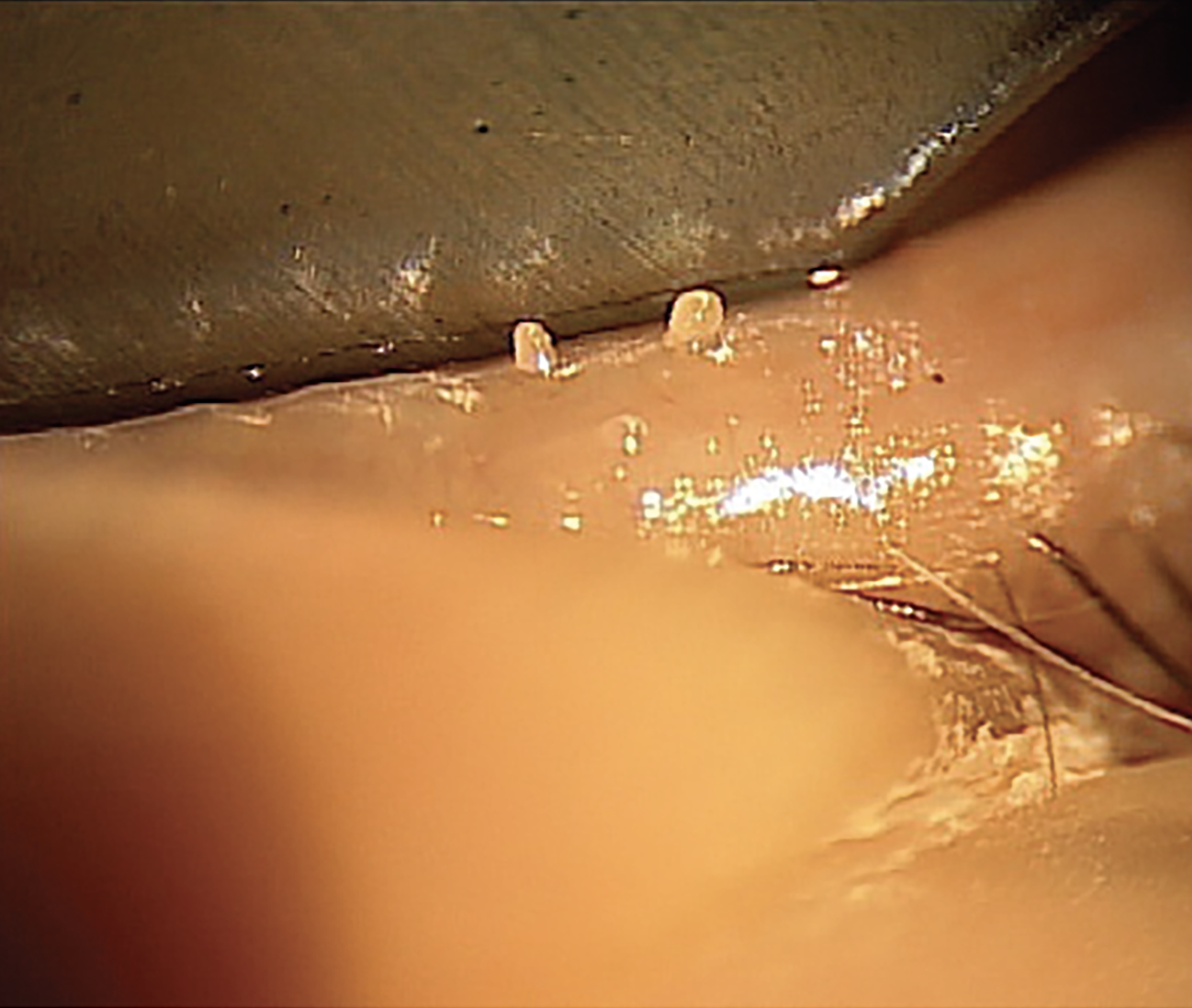

A postmenopausal woman in her mid-50s presents with a chief complaint of fluctuating vision and says she thinks her prescription glasses need updating. Meibomian gland expression is paste-like and there is only trace corneal staining and nasal conjunctival staining (Figures 1a and 1b). The patient reports that her symptoms worsen as the day progresses.

|

|

Fig. 1a. Expression shows thick and turbid meibum, indicating MGD. This patient would benefit from routine warm compresses. Click image to enlarge. |

Our routine initial dry eye workup for a patient who presents like this always includes meibography. It is important to show patients the damage to their meibomian glands; think of this step as being equivalent to the OCT of the optic nerve head in glaucoma. A picture can educate a patient in a powerful way. As we know, 86% of all dry eye patients have meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), and prevalence is higher in menopausal and postmenopausal women.1

Our recommended treatment plan would include a combination of an in-office thermal-pulsation treatment such as LipiFlow (Johnson & Johnson Vision) and a prescription dry eye medication, which in this case would be Miebo QID OU (perfluorohexyloctane ophthalmic solution; Bausch + Lomb), the first FDA-approved drop to target evaporative dry eye. The drug mimics the function of the lipid layer and thus is especially suited to patients experiencing symptomatic MGD.

|

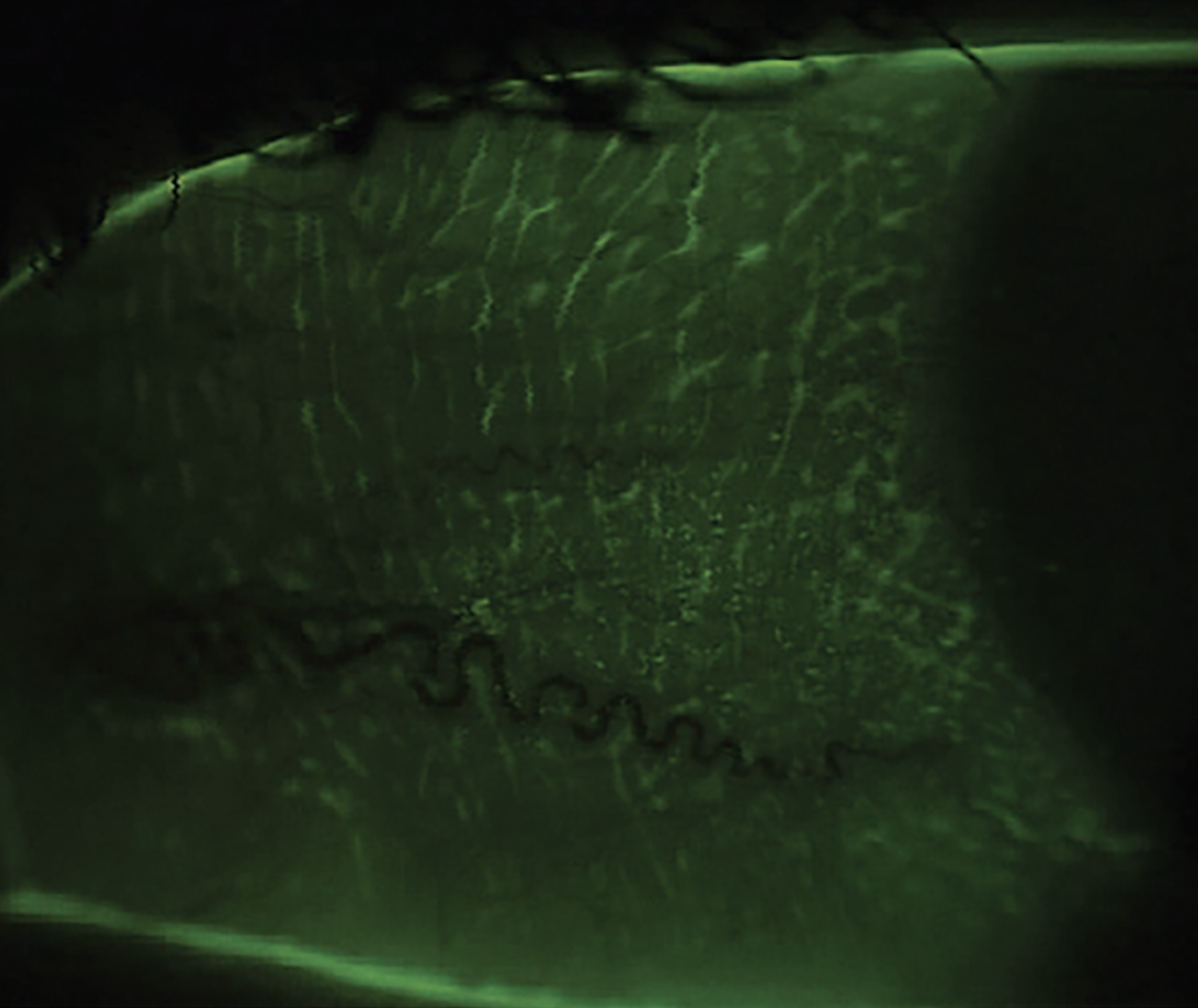

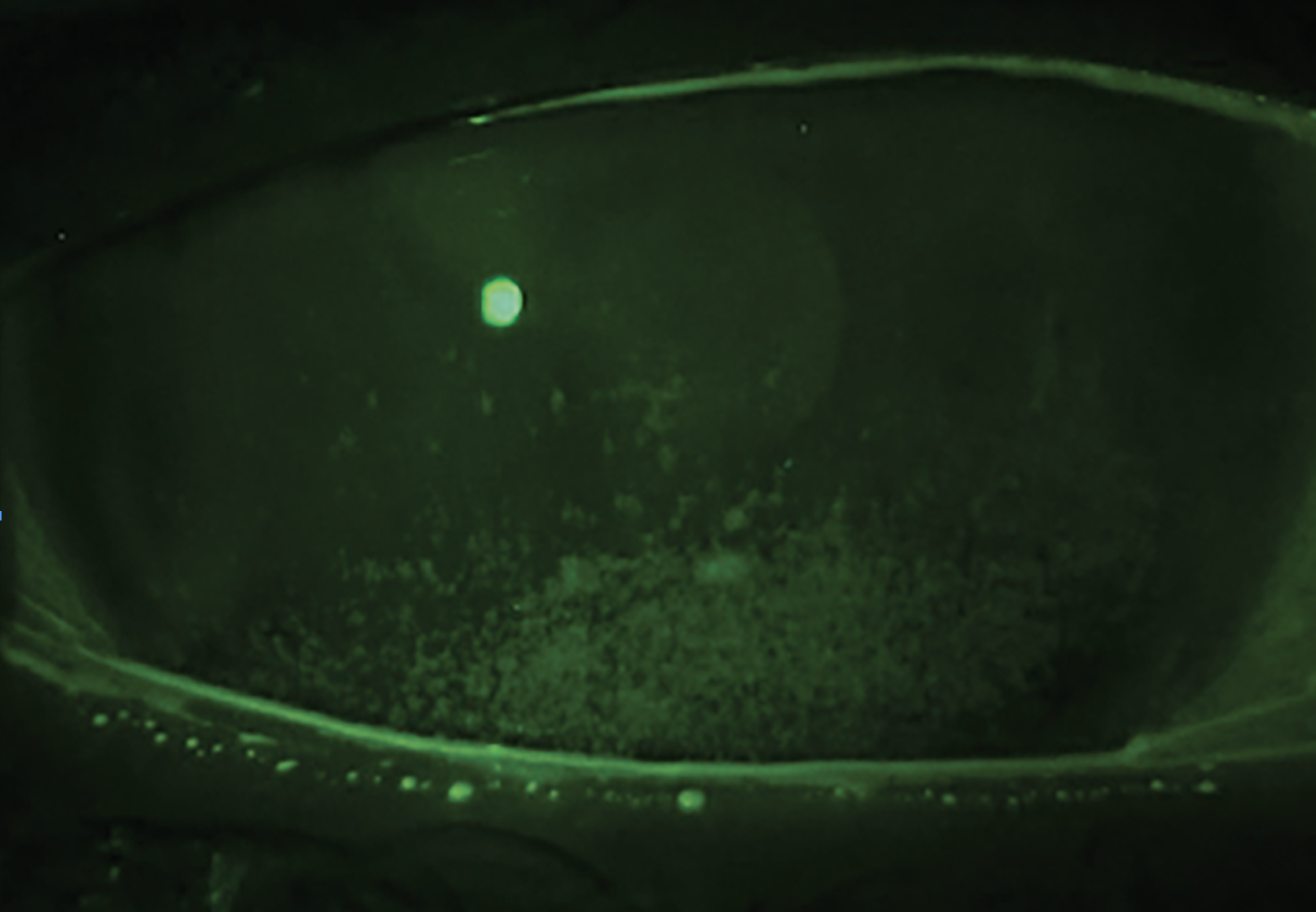

| Fig. 1b. Trace conjunctival staining with NaFl and a Wratten filter, the latter of which helps to detect subtle conjunctival staining without using other irritating dyes. Conjunctival staining indicates damage to the mucin-producing goblet cells. A nighttime ointment with vitamin A is a useful treatment for this type of staining. Click image to enlarge. |

In addition, we would recommend the patient take an oral omega-3 fatty acid supplement. Although there has been some controversy concerning the value of omega-3s in dry eye disease, most studies demonstrating its benefit recommend 3,000mg per day (2000mg of EPA and 1000mg of DHA).2 Consider starting out with 2,000mg per day and go from there depending on tolerability and result.

It is also important to educate this patient that use of at-home warm compresses should be maintained; we would suggest a Bruder mask (Bruder Healthcare) or similar moist heat compress. It is important to educate our patients that the traditional warm washcloth does not provide the same heat retention.3 Depending on the severity of the MGD, we recommend anywhere from five to 10 minutes daily or every other day sessions. It is important to note that in some cases, such as in ocular rosacea patients, the heat may exacerbate the inflammation and regular warm compresses may not be recommended.

Many dry eye patients assume that once they are treated with the LipiFlow procedure, they will no longer need to do the warm compresses. This is incorrect. Patient education is key to assure these individuals understand that they’re dealing with a chronic condition, and consequently, the combination of in-office and at-home therapy is essential to keep irritating symptoms at bay.

Case 2: Systemic Disease Origin (e.g., Sjögren’s Syndrome)

|

|

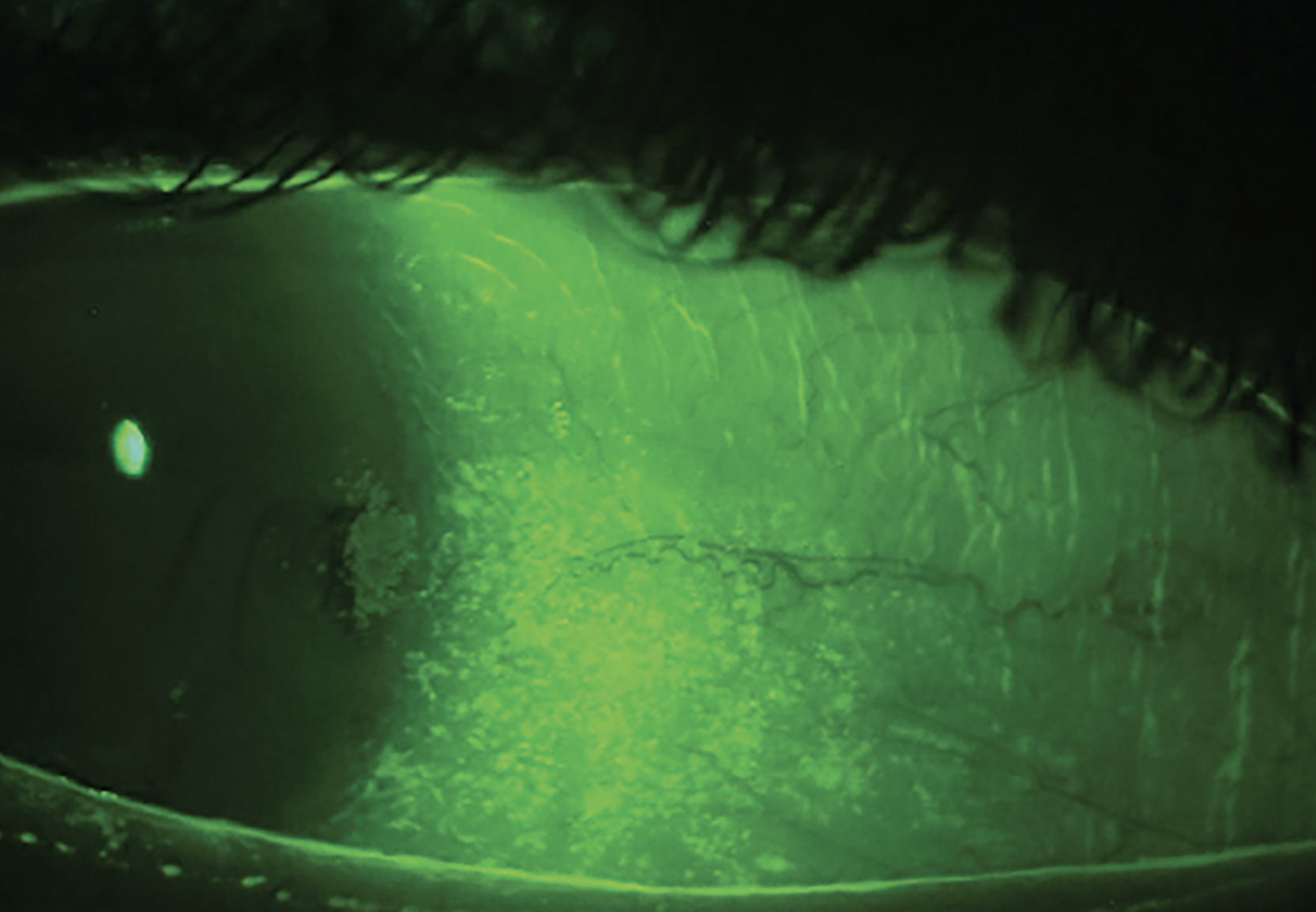

Fig. 2a. Grade 2-3+ conjunctival staining with patchy corneal staining. This is a common staining pattern seen in Sjögren’s syndrome. NaFl and a Wratten filter highlight conjunctival staining and show damage to the goblet cells and mucin layer of the tear film. Significant temporal conjunctival staining, patchy corneal staining and a reduced tear meniscus seen together warrant testing for Sjögren’s syndrome. Click image to enlarge. |

A patient presents with photophobia, extreme dryness and difficulty keeping her eyes open, in addition to blurred vision. Gland expression is slightly turbid but expresses easily, and the patient has grade 3+ patchy corneal staining, grade 3 conjunctival staining and a scant tear meniscus (Figures 2a and 2b). She has been on cyclosporine drops in the past with no improvement and is currently using artificial tears every one to two hours during the day and a bland ointment at night.

Our first step would be to ask a few additional questions; for one, what concentration of cyclosporine was she using, and how long was she taking it? It’s also beneficial to ask questions regarding the patient’s systemic health, such as any personal history of dry mouth or joint pain and any family history of autoimmune disease.

Our routine initial dry eye workup also includes the Schirmer test of tear volume. While there are certainly differing opinions on the validity of this test, at our practice we teach our students and residents that this, along with a reduced tear meniscus, is a good way to know that you are dealing with aqueous-deficient dry eye.

Another test included in our initial dry eye workup is InflammaDry (Quidel), which helps guide the decision of whether to prescribe an anti-inflammatory drop. The test quantifies the level of MMP-9 (an inflammatory marker) in the tear film. “Soft” steroids such as loteprednol are widely used on- and off-label to treat inflammation associated with dry eye.4

|

|

Fig. 2b. Grade 3+ coalesced corneal staining and a reduced tear meniscus in a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome. Click image to enlarge. |

Although we tend to manage these types of patients aggressively, we do prefer a stepwise approach. In this case, our treatment strategy would be to start with a prescribed dry eye drop for her significant ocular surface disease. If she was on 0.05% cyclosporine, we would recommend either 0.09% cyclosporine or the latest topical cyclosporine, Vevye (cyclosporine 0.1%, Harrow Health). Lifitegrast (Xiidra, Bausch + Lomb) is also an option. In conjunction, we would prescribe a topical steroid such as Eysuvis (loteprednol etabonate 0.25%, Kala Pharma) QID for at least two weeks with a taper. Of course, insurance coverage is always a factor in these decisions.

Punctal plugs are certainly an option after the patient’s inflammation has improved. At SUNY, we prefer to use the six-month dissolvable plugs as opposed to silicone plugs due to occasional issues such as infection, irritation, retention issues and granulomatous formation that can arise when silicone plugs are left in for prolonged periods of time.5

This is the type of patient who would require more clinic time. It is important that she understands that her condition is lifelong, and there are no quick fixes to permanently alleviate her discomfort. It is also important to explain that artificial tears will not resolve the underlying problem and, in fact, may mislead her to neglect a more serious health issue. We would educate her that there may be a systemic association with her dry eye and, given this possibility, order lab work such as antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor and Sjögren’s testing, along with a possible referral to a rheumatologist.

There are many treatment options for this patient, such as amniotic membrane placement as a short-term option for the keratitis, scleral contact lenses for long-term symptom management and vision correction if needed and, lastly, Regener-Eyes (Regener-Eyes) and blood-based drops such as autologous serum for longer-term treatment of ocular surface disease.

Case 3: Post-LASIK

A 43-year-old male, s/p LASIK, complains of longstanding severe dry eye since undergoing LASIK OU. He has seen multiple doctors and reports that he has “tried everything.” Exam findings show LASIK corneal scars, reduced tear film break-up time, no corneal staining and minimal MGD. His main complaint is “constant burning” in both eyes.

The first thing we ask patients is, “Can you tell me what bothers you the most about your eyes?” or “If you could only list one symptom, what would it be?” In this case, the patient complains of burning, which is one of the classic symptoms of neuropathic pain, aside from photophobia.

Next, we ask patients to tell us in detail exactly what they have tried and for how long. The second part of this question is vital, as some patients will prematurely stop taking a medication if they haven’t received realistic expectations about how long it takes for the full therapeutic effect to kick in. Though many patients think they have “tried everything,” there are often many treatment options left to tap into.

Our workup for this patient would include meibography, tear osmolarity, MMP-9 testing with InflammaDry, fluorescein and lissamine green vital dyes, tear meniscus height measurement, Schirmer or phenol red thread tests and meibomian gland expression. In this specific case, we would also perform an additional test known as the proparacaine challenge test. This is completed by asking patients to rate their pain level from one to 10. Then, a drop of proparacaine is placed in their eyes, and they are asked once again to rate their pain. If the pain is due to ocular surface disease, their pain score will improve after the instillation of the topical anesthetic. In patients with neuropathic pain, the pain score will remain similar.

The TFOS DEWS II report helped us to better understand neuropathic pain or “pain without stain” where the symptoms greatly outweigh the signs.6 There are multiple causes for this, and ocular surgery is one of them. These patients are our most difficult to manage, so our approach is to aggressively treat the ocular surface and any ocular inflammation. Preservative-free artificial tears and a topical steroid, such as loteprednol etabonate, are good starting points. We have used everything from topical cyclosporine and lifitegrast, amniotic membranes and scleral contact lenses to help these patients’ symptoms and have found particularly good success with the use of autologous serum drops.

To help improve these patients’ quality of life, some may also benefit from comanagement with a pain management specialist and treatment with medications such as gabapentin.7 It’s critical to spend the time to educate these patients on the root cause of their discomfort, as they often bounce from one doctor to the next for “dry eye” treatments when what they actually have is centralized neuropathic pain rather than peripherally located dry eye disease.

|

|

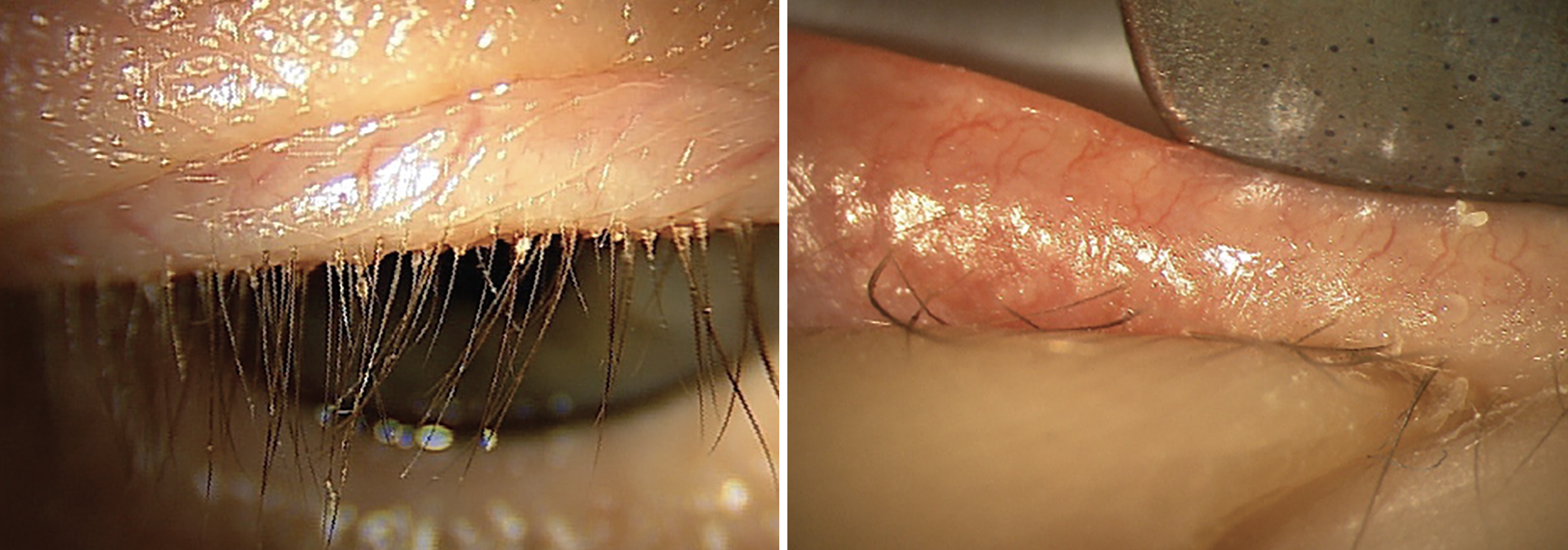

Fig. 3a. (Left) Grade 3+ collarettes at the base of a patient’s eyelashes. Collarettes are pathognomonic for Demodex blepharitis. It is important to have patients look down to examine the base of the eyelashes, as this finding is easily missed when the patient is looking straight ahead. |

Case 4: Demodex and Ocular Rosacea

A 57-year-old male patient presents with complaints of dry, gritty eyes and fluctuating vision. His complaints are worse in the morning, but he reports that his symptoms don’t improve much as the day progresses. Collarettes are noted on the eyelashes and telangiectasia on the eyelids with grade 2+ erythema (Figures 3a and 3b). Meibomian gland expression is minimal to none, with meibography showing more than 50% gland loss. However, tear meniscus height is close to normal. The patient has grade 2+ inferior corneal staining and trace conjunctival staining on the nasal and temporal areas. He reports that he has already tried artificial tears, hot compresses and lid scrubs, but he has not seen significant improvement.

First, we would look carefully at the skin around his face for signs of rosacea, a practice known as “external observation,” which we personally don’t think we do enough as optometrists. We would also ask the patient if he is under the care of a dermatologist. Then, we would perform the Korb-Blackie light test to look for an incomplete lid seal. The inferior superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) may be indicative of poor lid closure, which can cause patients to experience worse symptoms in the morning.

It's also appropriate to evaluate this patient for lid laxity and suspect floppy eyelid syndrome. We would ask if he has a history of deep snoring and/or sleep apnea; if a patient answers “yes,” ask about CPAP use, as misdirected air can cause severe inferior SPK in addition to the existing ocular surface condition.

This case represents a condition that is commonly seen yet often underdiagnosed. We are fortunate to have multiple treatment options for Demodex blepharitis and ocular rosacea. We would prescribe Xdemvy (lotilaner ophthalmic solution 0.25%; Tarsus Pharmaceuticals) BID for six weeks. Prior authorization is required and, currently, the prescription is sent in via online pharmacies such as Blink Rx, CVS Specialty, Carepoint and Alliance Rx. Although we have both found great success with Xdemvy, we still perform the in-office treatment for more advanced Demodex blepharitis patients, such as a 50% tea tree-based (Ocusoft) or okra-based product (Zest). The combination of both prescription ectoparasiticide medication and in-office blepharoexfoliation can also be a successful approach. Additionally, we would encourage the patient to use a lid scrub such as Ocusoft Plus (Ocusoft), MyboClean (Danelli Ocular Creations) or a lid spray such as Avenova (NovaBay Pharmaceuticals) or HypoChlor (Ocusoft).

Topical azithromycin 1.0% (AzaSite, Thea Pharma) is one of our favorite topical medications for rosacea-related blepharitis (not demodicosis). We tend to prescribe it once at bedtime for two weeks. Since this is a thick drop, we ask patients to close their eyes, smear the excess on their lids and lashes and then go to bed, since it can blur vision. After the course of AzaSite is complete, we ask that patients with floppy eyelids and incomplete lid closure use a lubricating ointment at night.

Patients with nocturnal inadequate lid closure benefit from using night seals to keep the eyelids closed while sleeping. SleepTite/SleepRite (Eye SleepTite) is a hypoallergenic, latex-free, oxygen-permeable patch that we recommend. We educate patients to tape one eye and use ointment in the other eye for patient safety and alternate eyes each night. Taping one eye at a time at night is safer to start with as a precaution, as patients may get up in the middle of the night to use the restroom and forget their eyelids are taped. Once the patient is comfortable with this regimen, we can consider patching both eyes overnight.

Once again, it’s important to reiterate that it’s best to steer clear of warm compresses in patients with ocular rosacea to avoid increasing inflammation and discomfort.

We would offer four sessions of intense pulsed light (IPL) for this patient to help treat the ocular rosacea and facial rosacea.8 Oral doxycycline is also great option for this patient, and we would likely wait to perform the IPL once they have been off doxycycline for at least a month. The decision to offer doxycycline before or after IPL, or not at all, is case-dependent. When there is both significant ocular and facial involvement, we start the doxycycline first to calm down the overall inflammation. Another reliable option is azithromycin, which may allow for a shorter treatment course and lower incidence of gastrointestinal issues.9

Finally, this patient should be comanaged with dermatology and referred for a sleep study if sleep apnea is suspected.

Case 5: Glaucoma

A 62-year-old patient complains of dry, red irritated eyes for many years. She has been diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma and her current medications include Combigan BID OU and Travatan qHS OU. The slit lamp exam reveals diffuse SPK, erythema of the inferior palpebral conjunctiva and diffuse conjunctival injection, especially inferiorly OU.

We receive many referrals from doctors who treat glaucoma. Managing patients with both glaucoma and ocular surface disease can be quite complicated. We know that their glaucoma medications are the main culprit, but also recognize that their intraocular pressure must be controlled.

It may sound simple, but everting the upper eyelid is essential when evaluating ocular surface disease. It is important to look for any asymmetry in the superior and inferior palpebral conjunctiva. In cases of medication toxicity, we often see more inferior palpebral conjunctival inflammation.

We tend not to prescribe an additional topical medication for their ocular surface disease in fear that the drops will affect their adherence to the glaucoma therapy that they are already prescribed. If the patient was only on one drop at night, then we might consider adding cyclosporine or lifitegrast BID OU.

Our first step in treating this patient would be to switch to preservative-free glaucoma medications if possible, or consider Vyzulta (Bausch + Lomb), which we have found to be less toxic to the ocular surface than latanoprost. In clinical trials, Vyzulta also showed greater eye pressure-lowering ability compared to latanoprost, which could help take patients off some of their glaucoma drops. We would also recommend selective laser trabeculoplasty, with the same hope of reducing or eliminating topical medications.

If the patient still feels that they need artificial tears, we recommend they use preservative-free formulations to minimize toxicity. Patients are educated to space out their lubricating drops with their glaucoma medications and reminded that no dry eye drop should ever replace their prescribed glaucoma therapy.

Tyrvaya (varenicline solution 0.03mg, Oyster Point Pharma), the first approved nasal spray for the treatment of dry eye disease, has become our top treatment choice for managing the ocular surface of patients who use topical glaucoma medications. It is a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist that stimulates the trigeminal parasympathetic pathway and is prescribed for twice-daily use intranasally.10 Tyrvaya can also be beneficial to prescribe to patients who have difficulty instilling drops, such as patients with significant arthritis causing dexterity issues in their hands. One thing to remember when prescribing this medication is to educate patients on proper instillation to the lower turbinates and avoid inhalation to minimize side effects such as excessive sneezing.

Who would have thought we would be prescribing a neurostimulator in the form of a nasal spray to our patients? This innovation is just one example of how considerably ocular surface treatment options have evolved compared to only five or 10 years ago.

Takeaways

Dry eye disease is chronic and multifactorial, presenting with a wide array of signs and symptoms and arising from multiple etiologies. As a result, it is critical to evaluate each unique patient to determine the best treatment, since in dry eye, “one size” certainly does not fit all. Fortunately, today, the availability of new diagnostics, treatments and pharmaceuticals has given us a greater armamentarium to care for these patients.

Dr. Canellos is a full-time faculty member of SUNY State College of Optometry. She is an associate clinical professor, instructor of record of the Fourth Year Program and director of the University Eye Center’s Referral Service. She supervises interns and residents in the anterior segment/cataract clinics of the Advanced Care Service. Dr. Canellos is a Fellow of the Academy of Optometry, a member of the American Optometric Association, NY State Optometric Association, Diplomate of the American Board for Optometry and a former member of the New York State Board of Optometry.

Dr. Koehler is an optometry resident focusing on ocular surface disease and cornea at Kentucky Eye Institute. She works with Paul Karpecki, OD, in clinical practice and research. Dr. Koehler graduated from Kentucky College of Optometry and is a member of the Kentucky Optometric Association. She has no financial disclosures.

1. Lemp MA, Crews LA, Bron AJ, et al. Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective study. Cornea. 2012; 31(5):472-8. 2. Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study Research Group N-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of dry eye disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1681-90. 3. Bitton E, Lacroix Z, Léger S. In-vivo heat retention comparison of eyelid warming masks. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39(4):311-5. 4. Beckman K, Katz J, Majmudar P, Rostov A. Loteprednol etabonate for the treatment of dry eye disease. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2020;36(7):497-511. 5. Horwath-Winter J, Thaci A, Gruber A, Boldin I. Long-term retention rates and complications of silicone punctal plugs in dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(3):441-4. 6. Belmonte C, Nichols JJ, Cox SM, et.al. TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):404-37. 7. Yoon H-J, Kim J, Yoon KC. Treatment response to gabapentin in neuropathic ocular pain associated with dry eye. J Clin Med. 2020; 9(11):3765. 8. Seo KY, Kang SM, Ha DY, Chin HS, Jung JW. Long-term effects of intense pulsed light treatment on the ocular surface in patients with rosacea-associated meibomian gland dysfunction. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2018;41(5):430-5. 9. Upaphong P, Tangmonkongvoragul C, Phinyo P. Pulsed oral azithromycin vs 6-week oral doxycycline for moderate to severe meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141(5):423-9. 10. Yu, M, Park, JK, Kossler, A. Stimulating Tear Production: Spotlight on Neurostimulation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:4219-26. |