Q: I have a patient who I believe has staph. hypersensitivity. The lids show significant blepharitis, the eye is diffusely red, and the cornea shows a small central infiltrate. How common is this, and what is the latest on treatment?

A: The condition is uncommon but not rare, says optometrist Michael W. Hung, of Atlanta. If a severe case is not treated aggressively, central corneal involvement can go downhill fast, progressing to thinning and eventually corneal perforation, he says.

In staph. hypersensitivity, some patients simply have an overgrowth of bacteria for unknown reasons, says corneal specialist Lawrence Woodard, M.D., also of Atlanta. Some patients are more prone to corneal involvement and a breakdown of the ocular surface. Bacteria lodge within the cornea, which leads to neovascularization and corneal infiltration.

The infiltrate simply represents the eyes immune response to the bacterial exotoxins, Dr. Hung says. Although the immune response is important for microbial destruction, its also associated with necrosis of the corneal collagen matrix and ground substance, resulting in corneal destruction, he says.

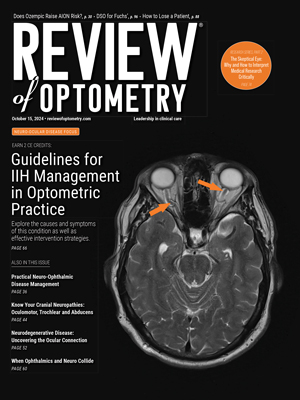

|

| Staph. hypersensitivity. |

Also, dont forget to treat the underlying etiology, which stems from the proliferation of bacteria on the lid margins, Dr. Hung says. Appropriate blepharitis treatment includes lid scrubs and warm compresses, he says. Artificial lubricants help to wash away bacteria and toxins from the eye surface.

Severe and chronic cases, he says, may warrant a topical antibiotic ointment or even an oral antibiotic, such as doxycyline 100mg b.i.d.

Q: Is there any danger of this condition causing more serious problems?

A: Yes indeed, Dr. Hung says. If not treated, bacterial strains adherent to the cornea can cause an infectious keratitis through any overlying epithelial defects. Further ulceration potential and scarring may have drastic effects on vision, especially if the central cornea is involved, he says.

Even after the infecting pathogen is eliminated, destructive enzymes and toxins can remain and continue to damage corneal tissue, Dr. Hung says. Further tissue necrosis can penetrate deeper into the corneal stroma, he says. More severe cases can even result in full-thickness corneal perforation.

If the condition is mild, with a small corneal infiltrate, no thinning of the cornea and no significant neovascularization, you can feel comfortable treating it with a topical antibiotic and a steroid, Dr. Woodard says.

But if the patient comes in with more advanced disease, with a lot of corneal neovascularization and thinning in ulcerated locations, you should get some help from a corneal specialist, Dr. Woodard says. Once the eye reaches that point, it can go south very quickly, he says.

One novel approach to treatment at this point: using amniotic membrane tissue to cover the ulcerated part of the cornea, which can stop the destructive enzymes, Dr. Woodard says. Alternatively, corneal glue may be used to fill in the defect and halt the damage.

If there is a corneal melt, then a corneal or lamellar transplant is necessary, he says.