A 49-year-old white male presented with a painful red right eye and foreign-body sensation. He reported that the onset was four days earlier and that vision in that eye decreased each day.

The patients systemic history was significant for a myocardial infarction in 1988 and severe rheumatoid arthritis for many years. He was currently taking oral methotrexate, a cytotoxic immunosuppressant, 20mg a week and 10mg prednisone daily for the rheumatoid arthritis. Ocular history was unremarkable.

Diagnostic Data

The patients entering best-corrected visual acuity was 20/50 O.D. and 20/20 O.S. Pupils were equal, round and reactive with no afferent pupillary defect. IOPs measured 14mm Hg O.U.

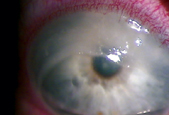

Biomicroscopy revealed 3+ bulbar conjunctival, episcleral and scleral injection in the right eye with no apparent scleral thinning. An arcuate shaped trough with no epithelial surface and 50% stromal thinning extended from 9:30-2 oclock at the limbus, and neovascularization extended into the thinned-out cornea.

Anterior segment evaluation in the left eye was unremarkable.

Opacification and thinning occurred secondary to the corneal melt in the patients right eye (left). Diffuse anterior scleritis in the eye was secondary to the rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnosis

I diagnosed diffuse anterior scleritis with a secondary corneal melt in the right eye.

Treatment and Follow-up

I placed the patient on 40mg oral prednisone qd and instructed him to return in five days. I did not consider prescribing a topical steroid because of the risk of increased corneal thinning.

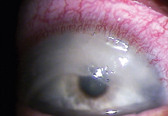

At the follow-up visit, best-corrected acuity was now 20/400 in the right eye, and the peripheral thinning and neovascularization had extended into the inferior temporal quadrant. I increased the dosage of prednisone to 60mg and added to the regimen 1gtt cyclosporine 2% qid. I also scheduled the patient for a consult with a corneal specialist.

I saw the patient six more times during the next two months, and the condition eventually resolved. During this time, I tapered the oral steroids. I also felt it necessary to comanage the patient with his primary physician, because corneal melting is often associated with systemic vasculitis.

Resultant scarring and thinning of the stroma at a six-month follow-up extended from 7-2 oclock. At this visit, the patients spectacle correction was -10.75 -1.75 x 015 for 20/30+ O.D. and -3.75D for 20/20 O.S. I scheduled the patient for future follow-ups every six months.

Discussion Corneal Melt: Two Common Systemic Associations Rheumatoid arthritis1,2 Wegeners granulomatosis1,4

A corneal melt, or peripheral ulcerative keratitis, is a serious condition that usually has an underlying systemic etiology. Collagen vascular disease is found in approximately 50% of all noninfectious peripheral ulcerative keratitis; rheumatoid arthritis is the most prevalent.1-3

Other autoimmune diseases have been linked to peripheral ulcerative keratitis. A high rate of ocular involvement also exists with Wegeners granulomatosis. Other associations include relapsing polychondritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Corneal involvement has been documented with SLE, though rarely, and usually is secondary to keratoconjunctivitis sicca.1,4

Corneal melting also is a rare complication of Sjgrens syndrome.5 Indeed, cases of corneal melting have been reported in patients with established Sjgrens syndrome, usually secondary to rheumatoid arthritis.5

Affects 3% of the adult population, one of four of whom develop ocular involvement.

Found at a higher incidence in women (3:1).

Mean age of onset at age 63.2.

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is usually not the presenting sign of RA but occurs 12-35 years after the initial diagnosis.

Systemic signs of RA include morning stiffness lasting greater than 1 hour, swelling of the soft tissue of three or more joints, subcutaneous nodules and serum rheumatoid factor.

Patient may present with severe ocular pain, photophobia, foreign-body sensation, keratoconjunctivitis sicca and decreased vision.

Autoimmune disorder.

50-60% of cases have ocular involvement.

Ocular manifestations (conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis) are often the presenting signs of the disease.

Systemic signs include respiratory symptoms, urinary tract involvement, sinusitis, arthritis, positive ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody).

Granulomas form in different parts of the body due to cell debris from inflamed blood vessels.

For a definitive diagnosis of peripheral ulcerative keratitis, you must first rule out conditions with similar clinical findings. Moorens ulcer has a similar appearance and affects the peripheral cornea. It may be associated with hepatitis C virus and other systemic etiologies, but is not commonly associated with collagen vascular disease.3 A benign, typically unilateral type seen in an older population responds well to treatment; an aggressive, typically bilateral type seen in a younger population does not respond as well to treatment, and often proceeds to the central cornea. Pain associated with Moorens ulcer varies depending on the type and presentation.4

Terriens marginal degeneration also has similar characteristics to a corneal melt. However, it is often an asymptomatic bilateral condition seen in younger men. It does not typically occur with injection, but it does progressively thin the peripheral cornea, sparing the limbus. This condition often goes unnoticed because of its slow progression over several years.4

Corneal melts affect the peripheral cornea at the limbus in a circumferential manner and are associated with an epithelial defect and stromal changes. In most cases, melts are associated with inflammation of the adjacent conjunctiva, episclera and sclera.1

Unlike the avascular central cornea, blood vessels extend approximately 0.5mm into the peripheral cornea to provide nourishment. Circulating immune complexes are deposited in these vessels, resulting in inflamed vessels or vasculitis. The leakage of inflammatory cells that results leads to the release of collagenase and other proteases that destroy the corneal stroma.3

Prompt treatment of the ulcer is essential to preserve vision. Initial treatment involves oral steroids of varying dosage, depending on the severity of the condition. A cytotoxic agent is often necessary as well. When immunosuppressive therapy is indicated, cyclosporine may be used topically or orally, as well as oral methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine.3,6

Topical steroids are contraindicated. These can initiate and complicate a corneal melt.

Patients with melt and impending perforation should wear safety glasses or at least corneal shields at nighttime. Spectacles should be sufficient during the day.

Past studies have shown that peripheral ulcerative keratitis may represent the onset or progression of the vasculitic phase of rheumatoid arthritis. However, peripheral ulcerative keratitis does not usually present early on in RA but 12-35 years after the initial diagnosis.5

In contrast, corneal melt is often the presenting sign of Wegeners granulomatosis. Thus, the patient is not only at high risk for visual loss, but he or she is also at high risk for potentially life-threatening systemic complications if left untreated.6 For this reason, comanagement of these patients with a rheumatologist or the patients GP is important.

The patient had this appearance at his one-week follow-up visit.

Surgery is indicated for melts that have progressed to advanced stages. Conjunctival resection may decrease conjunctival production of collagenases and reduce immune cell transfer to the peripheral cornea. Other treatment options include penetrating keratoplasty, lamellar grafts, use of tissue adhesive and bandage contact lenses, and amniotic membrane transplant. Unfortunately, corneal transplantation has had poor results due to severe dry eye problems and recurrence of the ulcerative keratitis.1

This case is an example of the optometrists role in a patients overall health. As our scope of practice is continually expanding, we will manage more patients who manifest ocular complications of systemic disease. Besides treating their ocular disorders, well need to make timely referrals to other doctors to provide the most appropriate care to our patients and possibly save their lives.

Dr. Harshman practices with the Veterans Affairs Medical Center Eye Clinic in Spokane, Wash.

1. Ladas JG, Mondino BJ. Systemic disorders associated with peripheral cornea ulceration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2000 Dec;11(6): 468-71.

2. Messmer EM, Foster CS. Destructive corneal and scleral disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Medical and surgical management. Cornea 1995 Jul;14(4):408-17.

3. Dana MR, Qian Y, Hamrah P. Twenty-five-year panorama of corneal immunology: emerging concepts in the immunopathogenesis of microbial keratitis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, and corneal transplant rejection. Cornea 2000 Sep;19(5):625-43.

4. Starck T, Hersh P, Kenyon K. Corneal Dysgeneses, Dystrophies and Degenerations. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, Azar DT. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 2000:740, 815-21.

5. Vivino FB, Minerva P, Huang CH, Orlin SE. Corneal melt as the initial presentation of primary Sjgrens syndrome. J Rheumatol 2001 Feb;28(2):379-82.

6. Squirrell DM, Winfield J, Amos RS. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis corneal melt and rheumatoid arthritis: a case series. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999 Dec;38(12)1245-8.