|

| This old projector chart shows a single column of letters. Click image to enlarge. |

For well over a century now, our profession has mainly been associated with one of the many critically important things we provide for our patients: prescriptions that translate into glasses and/or contact lenses. Eyewear dispensed from these scripts is what the public usually sees as the end goal of going to the optometrist’s office. This article will explore tips, tricks and techniques I’ve developed over 40 years of both performing and teaching refraction to aid patients in obtaining clear, single, binocular vision when possible and to help them accomplish all the things they wish to do in their lives.

Work With a Range

I once believed only one prescription should emerge from each examination. However, in nearly all instances, a range of potential lenses could be prescribed to a patient, all of which would help meet their needs. We must ditch the mindset that comes with working with one prescription and look for the range of lenses available for any given patient. It’s up to us to help patients understand that there is no one perfect lens.

We can look at prescribing as a negotiation between the doctor and the patient. If we end up with a single lens to present our patient with, the negotiation is simple and not much of a negotiation at that. Asking whether or not it is satisfactory yields a yes or a no. If we have a range of lenses, the patient has a choice to make. Do they want maximum visual acuity at distance even if it impacts their reading speed or comprehension level when used at near? Or maybe they want to be able to do a specific task, such as playing a musical instrument or competing in a sport. The better we understand a patient’s wants, needs and priorities and the more options we’re able to give them, the higher the chance we’ll be able to work together to narrow in on the best solution. Approaching the situation in this way could lead to multiple prescribing opportunities. This is a win-win scenario—happier patients help your practice grow, both financially and patient-wise.

A case-in-point of multiple prescriptions is my own vision. I have a general-purpose pair of Trivex Transitions for everyday use. However, I can’t use these glasses while fulfilling my clinical teaching duties, so I have an occupational pair of Trivex trifocals, which allow me to clearly see my dual screen setup and my patients’ faces during case presentations from five to six feet away without having to tilt my head back. I have another pair I wear while playing my bass trombone that are single vision to match the intermediate of my occupational glasses. I also have a pair of polarized multifocal lenses for driving and enjoying the outdoors. When I get a new prescription, I get four new pairs of glasses.

Get In, Get Out…Efficiently

Patients have limited attention spans as is, and that’s before taking into account the fact that they’re sitting in an optometrist’s office when they could be literally anywhere else. This doesn’t mean we should cut corners during our exams. It does, however, mean that we should be efficient and use our time wisely before we lose the patient.

An example of saving time while not negatively affecting outcomes has to do with taking visual acuities. We all know that deciding whether a letter on the chart is a “C,” an “O” or a “G” can be difficult and time-consuming for some patients. All we really need is a quick way to know if something has changed between appointments. Getting acquainted with computerized visual acuity measuring systems and developing a testing methodology that goes from non-seeing to seeing allowed me to obtain visual acuities far quicker and with more precision than I ever could before. Instead of getting the generalized 20/25+, I could get 20/23 in about half the time. By focusing on what our patients are seeing and how we’re showing it, we can shave time off our testing sequence without sacrificing our precision.

Another example of efficiency in action involves our refraction routine. As taught, we typically do a nearly complete monocular refraction of the right eye and then the left eye before moving to the binocular balance. This includes finding the sphere power we have in place for our cylinder testing.

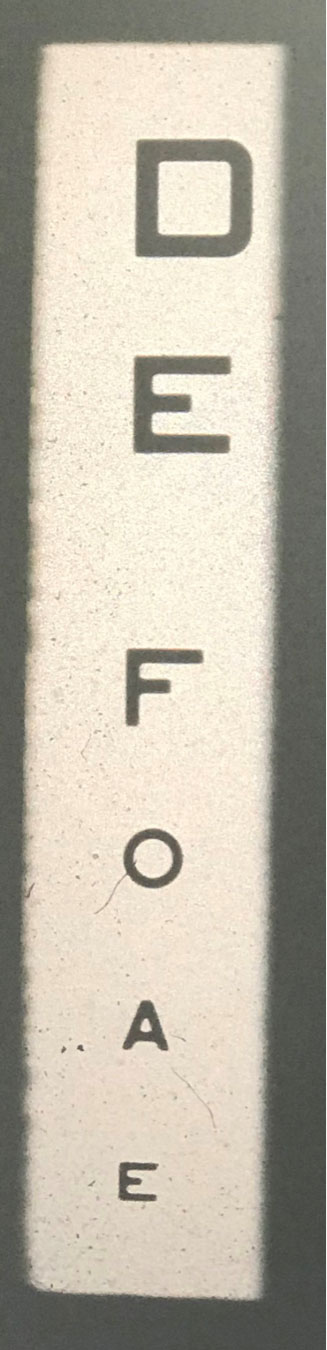

After retinoscopy, I recommend using an open chart from 20/70 to 20/40 or so depending on your chart options, with half of the letters shown in red and half in green, and asking the patient which side is blackest or clearest. With one or two clicks, you can find where the change is occurring and proceed with cylinder testing. To do this efficiently, I test the right eye first and then move to the left eye. With most patients, I then go to a single 20/40 line to do my cylinder testing and switch between eyes. Minimal chart changes and eye rotations are efficient ways to save time.

Take the Pressure Off

“Which is better, one or two?” is the part of the eye exam comedians seem to gravitate toward when they do routines about going to the optometrist. One of our patients’ greatest fears is that they will get the wrong pair of glasses if they give us one wrong answer. I realized early on that if I let the patient dictate how this part of the testing should go, they end up asking me to repeat the slides any number of times. So, I emphasize that they should give me their first impression and, even if they start to second-guess themselves, we will end up where we need to be.

It doesn’t help when we flip the lenses from one choice to another too quickly during an exam. The patient is given very little time in between to focus on what they’re seeing and decide where it ranks. This necessitates many flips and leaves patients feeling certain they made a mistake. I have found that staying on each choice for about three seconds leads to a definite selection after only one flip the majority of the time.

|

| This open chart from 20/70 to 20/40 shows half of the letters in red and half in green. Click image to enlarge. |

Don’t Take Shortcuts

Some believe that after a certain age, since accommodation might be considered non-functioning or functioning to such a small degree, we only need to perform monocular refractions. This, however, could cause visual problems later on. Obtaining the binocular balance (most plus or least minus to the first good 20/20) gets us one end of the range when prescribing. Even though this number is usually not included in the final prescription, it’s nice to have it, especially if we are concerned about progressive myopia or accommodative esotropia. We also use it to step down binocularly and remove plus or add minus to get to our best visual acuity lens. This is the other end of the range, from which our prescription options emerge.

Find the Right Tools

For some of our colleagues, the near point rod for the phoropter might be used more as a back scratcher than as something that holds the near point card. But, I’ll assume you do near point testing, at least some of the time.

I purchased the Rotochart (Ametek Ultra Precision Technologies, Reichert Technologies) as an optometry student and have used it my entire career. The device has 12 different charts, six per side, that the user can easily rotate through. I’ve watched countless times as your typical cards get misplaced. The Rotochart, and others like it, has helped solve this problem for me.

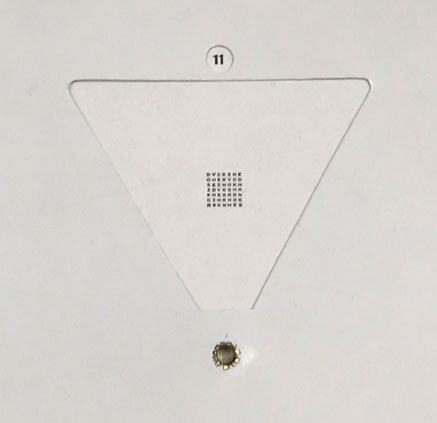

I use chart 11, an 8x8 block of 20/20-sized letters, most often for near phoria testing to obtain the positive and negative relative accommodations. I’ve learned to check in with my patients to make sure they understand what I’m asking for. As I move to lens powers that I know should create some blur and patients still report the letters as clear, it tells me that they don’t. When I ask them to read a specific letter further down on the chart and they can’t, it shows that we’re on different pages.

What I assume is happening is that they are continuing to look at the first line rather than being on the lookout for any changes happening as a whole as I switch the lenses. So, I specify what I’m looking for and then reduce the lens power until the patient can first see the letters clearly. Whatever tool you pick for your arsenal may bring some hiccups, but finding what works best for you and educating the patient accordingly makes a world of difference in obtaining efficient, accurate results.

|

| This is chart 11 of the Rotochart. Click image to enlarge. |

Make Every Measurement Count

Phoria measurement is another one of those probes we all learned in school but may have stopped performing along the way, mostly because the data culled from the test never seems to be used in altering the prescription or treatment plan given to the patient. In reality, this finding helps predict the degree to which a patient will be able to use the lenses we prescribe.

I was taught to always perform a pair of phoria measures at each distance but with different lenses in place. I take a phoria through my refraction and another through plano, which is called the habitual. Be as consistent as possible during the testing by delivering the set the same way, using the same target and lighting, moving the prism at the same speed and conducting the two phoria tests as close together in time as possible. The key is to find the difference between the two measures, and taking all of these factors into consideration will give you the best shot.

For example, a new myope comes in and we find -0.50 yields a sharp, comfortable 20/20 OD, OS and OU. At that point, I take the phoria measure with the -0.50 in place and record it. Then, I immediately remove the -0.50 to get back to the habitual and take the phoria again. Often, the change in the phorias, or lack thereof, is more a measure of the choices the patient makes at the moment they look at the target. They may fixate on one point, shifting the phoria toward less exo or more eso. Or, they may focus on the bigger picture and take it all in equally and at once, showing more exo or less eso.

In general, I like to see more variability in each pair of phorias measured with different lenses because that signifies the patient is more flexible. When working with a patient where there is little to no fluctuation, I need to be more careful in prescribing to make sure that any change I make is truly warranted, else the patient might return far too soon for an encore refraction.

Refraction remains a core service—an art—provided by optometrists. Directed by science, but guided by a series of principles to encourage efficiency and accuracy, it allows today’s optometrists to serve the prescribing needs of patients far beyond what any automated system is capable of.

Dr. Harris teaches amblyopia, strabismus and pediatrics at the Southern College of Optometry. Clinically, he practices vision therapy, vision rehabilitation and hospital-based care for ABI/TBI, pediatrics and electrodiagnostics. He is actively involved in research looking into new ways to measure stereo acuity and visual acuity and how color can help patients who suffer from ABIs/TBIs, migraines and seizure disorders.