Determining the etiology of a patient’s complaint of double vision can be akin to a detective solving a mystery in a novel; it is best to approach the case in a stepwise fashion and ask the appropriate questions. Here, we present a four-step process with 20 questions to ask or consider during an eye exam when a patient presents with diplopia.

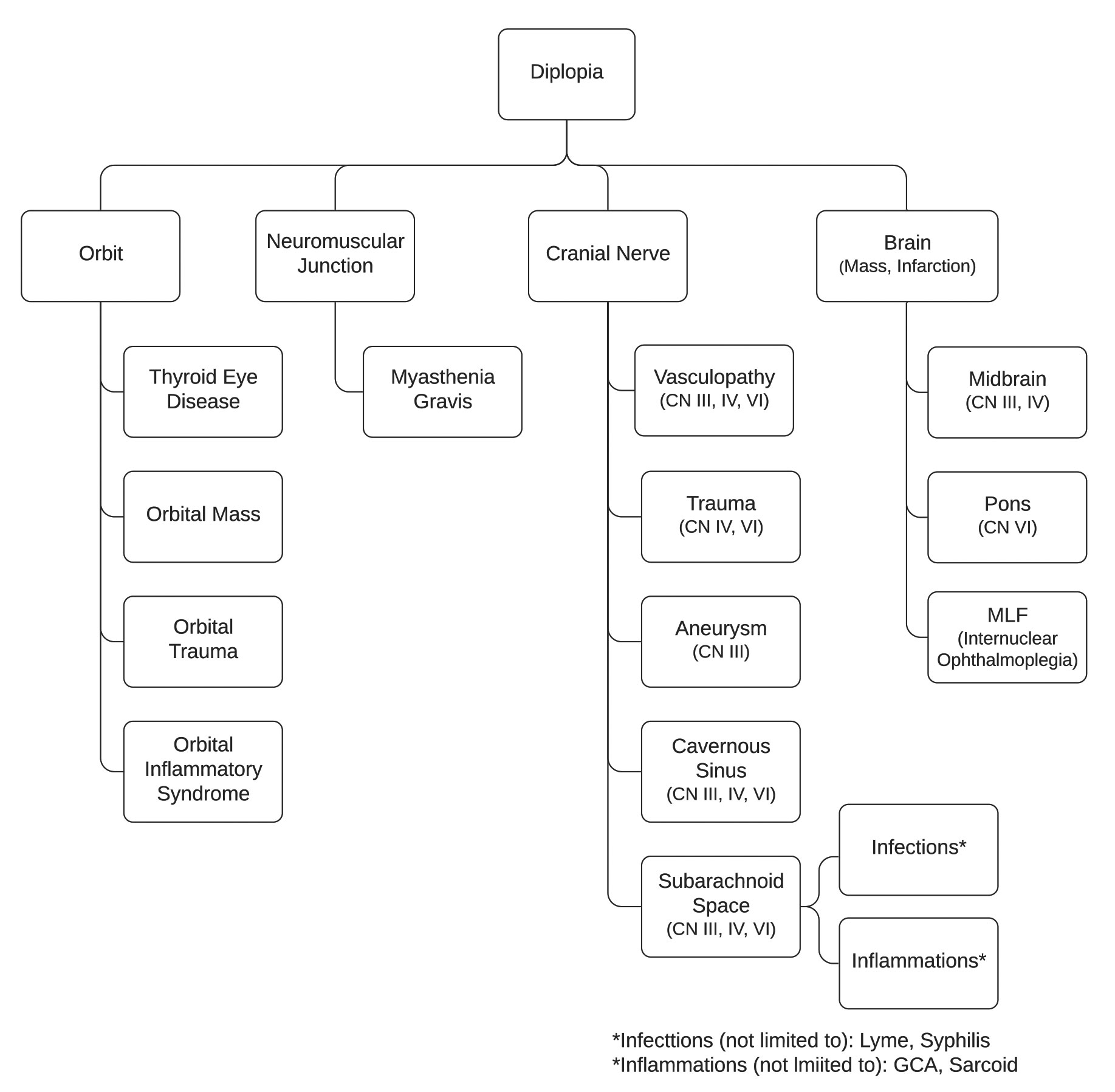

This guide will help anatomically localize the cause of the diplopia and create a differential diagnosis. As the eye care provider goes through the exam, these questions will help determine if the cause is in the brain, nerve, junction between nerve and muscle or orbit. Figure 1 presents some more common differentials for diplopia and their localization. Once they have created a differential diagnosis, the eye care provider will then be able to determine the appropriate management for their patient.

|

| Fig. 1. Localization of common etiologies causing diplopia. Click image to enlarge. |

Step 1: Weigh Binocular vs. Monocular Diplopia

The first step to uncovering the etiology is to determine if the patient has true binocular diplopia.

Ask the patient:

1. Does the double vision go away if you cover one eye?

If no, then we have monocular diplopia and our neuro-ophthalmic mystery ends here. At this point, we can narrow down the etiology to being confined to the ocular structures (cornea, lens or retina). These patients should have a refraction and thorough biomicroscopic examination of the ocular media.

There are a few rare cases where a patient may have monocular diplopia of neurological etiology. These patients are likely to have lesions of the parieto-occipital region.1

If the answer is yes, continue to question 2.

2. Does it matter which eye you cover?

If yes, then this is likely a case of monocular diplopia.

If no, then the patient likely has true binocular diplopia, and you need to continue to Step 2.

|

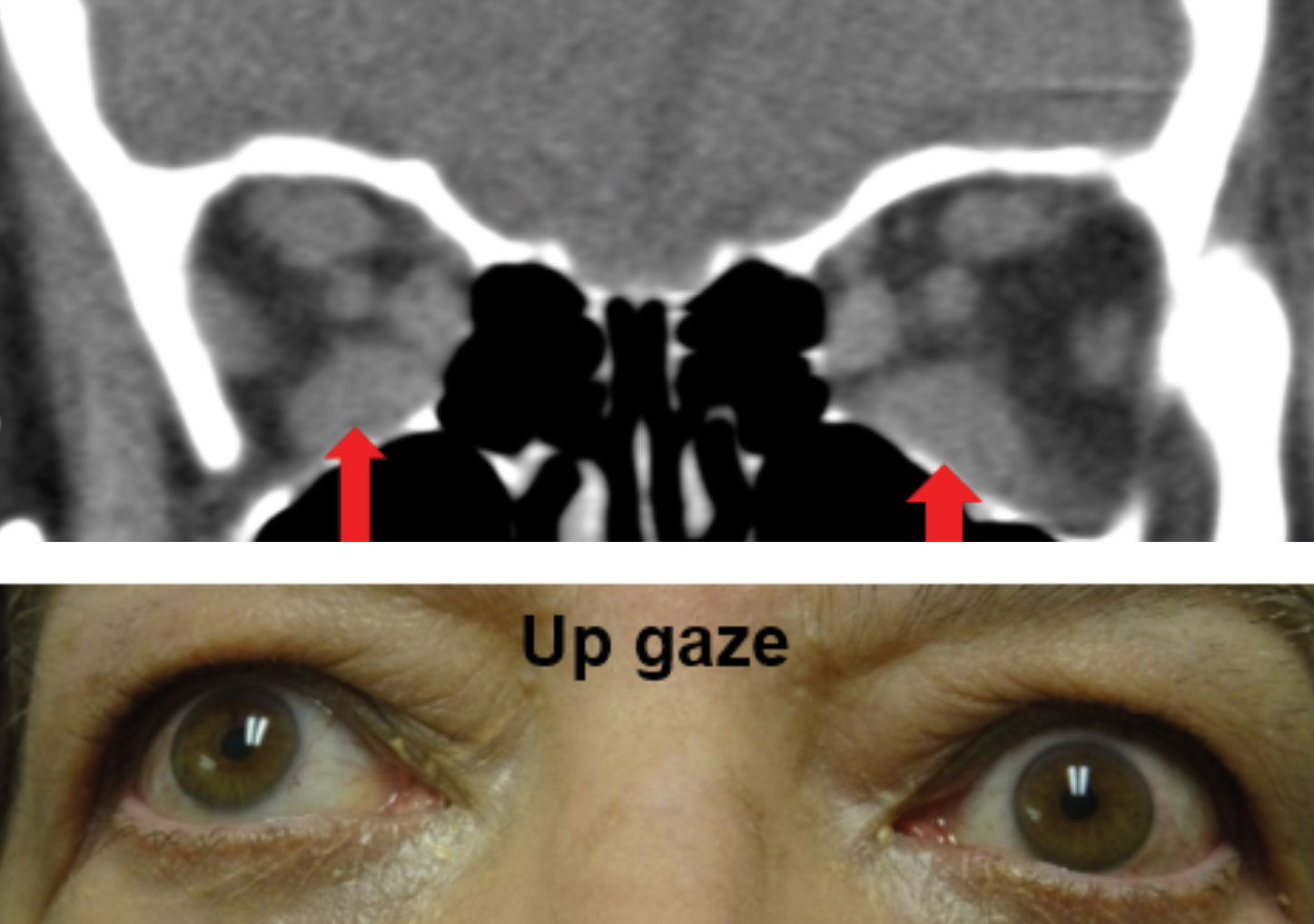

| Fig. 2. Enlargement of the bilateral inferior recti muscles OS>OD as noted with the red arrows on the CT scan above resulted in a bilateral supraduction limitations. Note the Purkinje image is higher on the cornea of the left eye, which is the eye with the greater supraduction limitation. Click image to enlarge. |

Step 2: Determine Misalignment Type

Ask the patient:

3. Is it constant or fluctuating?

A patient with intermittent or fluctuating diplopia can make the diagnosis more challenging because you may not be able to elicit the diplopia while in the exam room. Performing testing in different positions of gaze and at different distances may induce the diplopia. If the patient reports worse diplopia toward the end of the day or when fatigued, the leading differentials include myasthenia gravis (MG) and a decompensating phoria.

4. How are the images displaced (horizontal, vertical, diagonal)?

Direction Differential

Horizontal Medial/lateral rectus

Vertical/Diagonal Obliques, superior/inferior rectus, multiple extraocular muscles

Tilt Cranial nerve (CN) IV palsy or skew deviation

We now need to determine the pattern of diplopia in order to localize the problem and narrow down our differential diagnoses. Horizontal diplopia is more consistent with a lesion affecting the medial and/or lateral rectus, whereas vertical or diagonal may be more consistent with a lesion affecting the oblique muscles, superior rectus and/or inferior rectus or multiple extraocular muscles.

Some patients may also report a tilt to the images, which would indicate a torsional component and may point to a diagnosis of a CN IV palsy or skew deviation.

|

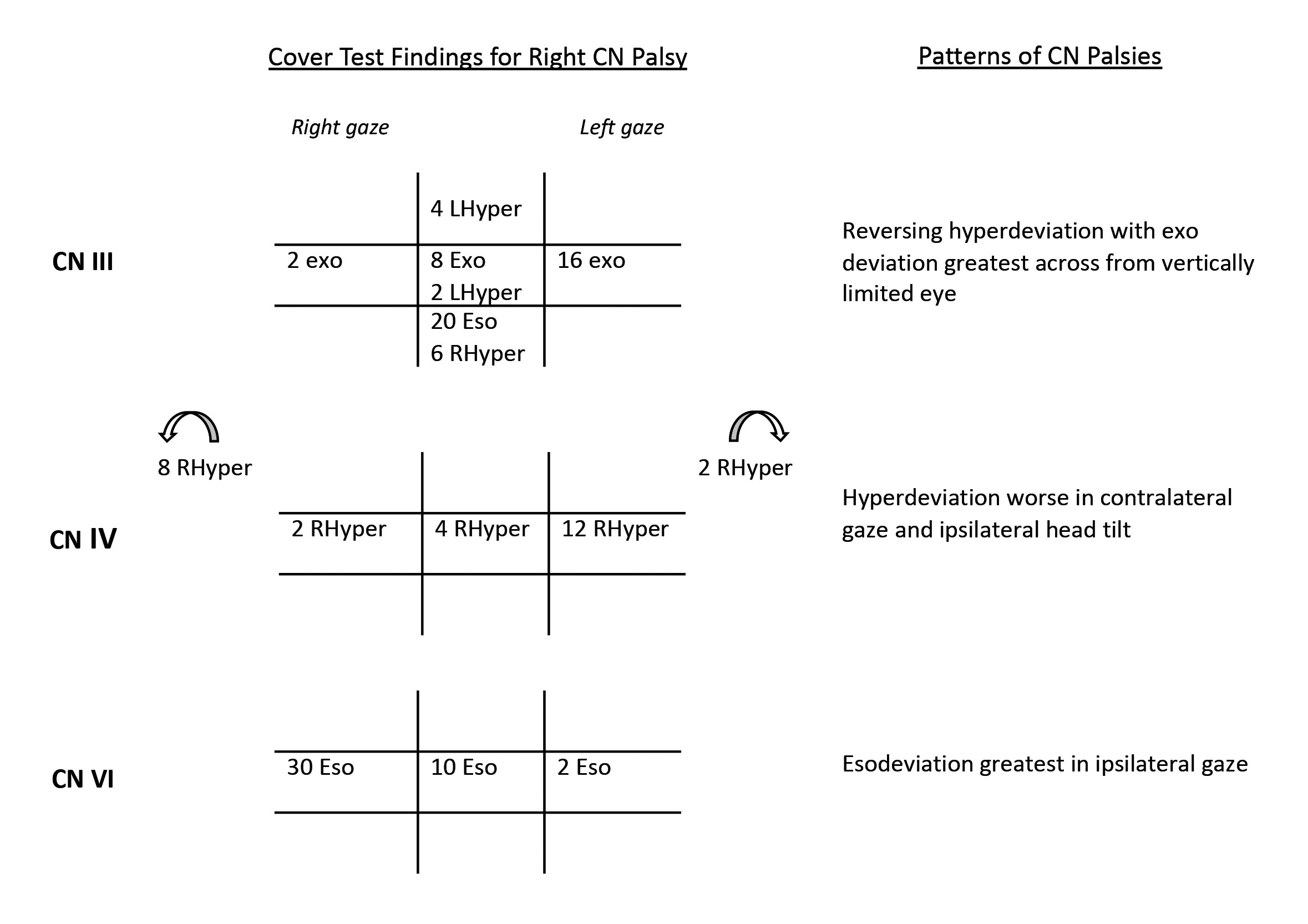

| Fig. 3. Patterns of right CN palsies (CN III, CN IV and CN VI) on cover test. Click image to enlarge. |

5. Is it worse in any particular distance (near or far) or direction of gaze (left, right, up, down)?

Many presentations of diplopia will have the same misalignment at all distances. If there is a difference, this can be helpful in narrowing the differentials. For example, horizontal diplopia, which is present at distance only, is more indicative of either CN VI palsy or a divergence insufficiency. Conversely, if the horizontal diplopia is only present at near, it may point to a convergence insufficiency.

Some causes of diplopia may only be present or worse in a particular gaze. If the cause of the diplopia is paretic, the diplopia will be worse in the direction of the paresis. If there is an orbital mass, the gaze of worsening diplopia may depend on where the mass is located in the orbit. If the mass is more anterior, such as in an enlarged lacrimal gland or a space-occupying lesion, the diplopia will be worse in the direction of the mass. If there is enlargement of an extraocular muscle, such as in thyroid eye disease, the diplopia will be exacerbated in the opposite direction of the affected muscle (Figure 2).

Observing the patient for a compensating head posture can also be helpful. A patient with a left abduction deficit will often have their head turned to the left to put the eyes in right gaze and minimize the diplopia. Additionally, a patient with CN IV palsy will often tilt their head to the contralateral side of the hypertropic eye.

6. How long has it been going on for and is it stable, worsening or improving?

Many patients presenting with diplopia may have risk factors for a vasculopathic etiology, such as diabetes, hypertension and smoking. However, if the onset of diplopia was greater than six months ago, then the etiology is not likely vasculopathic, and additional testing for other causes must be performed.

7. How did you first notice it?

This question will give the provider insight to any precipitating factor (i.e., trauma or stroke). Additionally, characteristics of onset may help determine etiology. For example, if they report only noticing the diplopia because they were performing a particular task, this can be revealing.

|

| Fig. 4. Maddox rod testing for horizontal and vertical misalignments. The red line is viewed with the right eye, and the yellow star represents the light source viewed by the left eye. A is the patient view if no vertical deviation. B is the view if no horizontal deviation. C is the view of a right hyper deviation. D is the view of an exo deviation. Click image to enlarge. |

8. Any history of childhood strabismus or prior orbital surgery?

If the patient has a history of being treated for strabismus or strabismic amblyopia as a child, such as with patching, this may indicate that they are now experiencing a decompensating phoria resulting in diplopia. However, the exam findings must be consistent with this diagnosis. If there is a noncomitant deviation, then additional etiologies must be ruled out. Note that other types of surgeries, such as cataract, glaucoma or scleral buckle for a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, can also result in diplopia.2-4

Ask yourself during the exam:

9. Do I see any ductional limitation?

Careful assessment of ocular motilities frequently helps with localization.5 It is important when performing versions that you put the patient’s eyes in the fullest extent of their gaze. Purkinje images (PI) can be useful in assessing ductional limitations, particularly in vertical gazes (Figure 2).

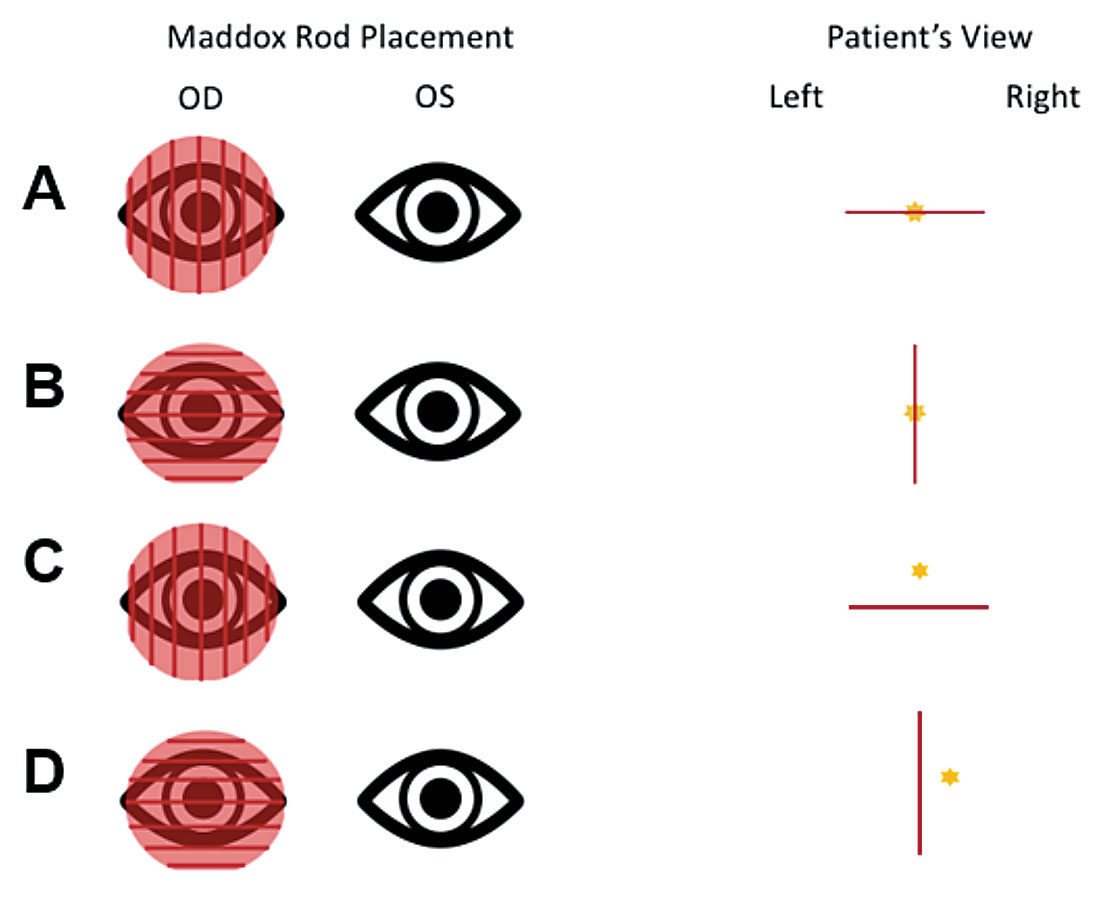

10. Does my cover test or Maddox rod testing in different positions of gaze match the pattern of a specific CN palsy?

This is one of the most helpful in-office tests in localizing a lesion causing diplopia. There are specific patterns of deviation that help identify isolated CN palsies. The results of a cover test are objective and the test does not require a verbal response from the patient. Additionally, a cover test can be helpful in determining a constant from an intermittent strabismus or a phoria. Conversely, Maddox rod testing requires that the patient understand the test and be able to give a verbal response. Figure 3 demonstrates the classic patterns of CN III, IV and VI palsies.

Maddox rod testing must be performed twice in each position of gaze: once with the cylinders oriented vertically, creating a horizontal red line to assess the vertical deviation, and again with the cylinders oriented horizontally, creating a vertical red line to assess the horizontal deviation (Figure 4).

The Parks-Bielschowsky three-step test is useful in diagnosing an isolated unilateral CN IV palsy. This palsy pattern is a hyper deviation greater on contralateral gaze and ipsilateral head tilt. Although this is a very useful test, it is not 100% sensitive. The test may fail to diagnose in approximately 30% of cases.6

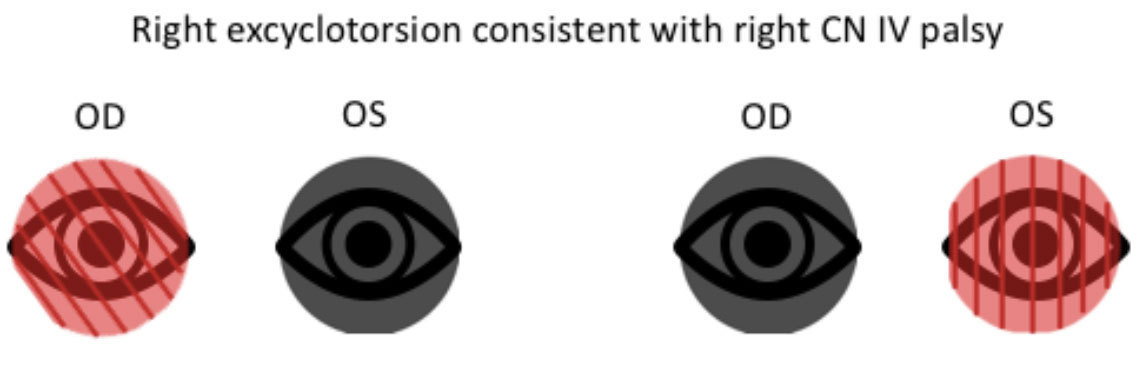

11. If there is a vertical deviation, are the double Maddox rod results abnormal?

Double Maddox rod testing is helpful in assessing for torsion and should be completed on all patients presenting with a hypertropia. Place the Maddox rods in both oculars of a trial frame. Cover one eye and ask the patient to rotate the cylinder until the line appears perfectly flat. If the cylinders are not aligned at 90º, this indicates torsion (Figure 5). Do this for both eyes.

Clinical Pearls: Assessing Ocular MotilityOn lateral gaze, the sclera of both the abducting and adducting eyes should be buried. On up gaze, the eye with the PI higher on the cornea is the more limited eye. On down gaze, the eye with the PI lower on the cornea is the more limited eye. |

Step 3: Localizing the Lesion

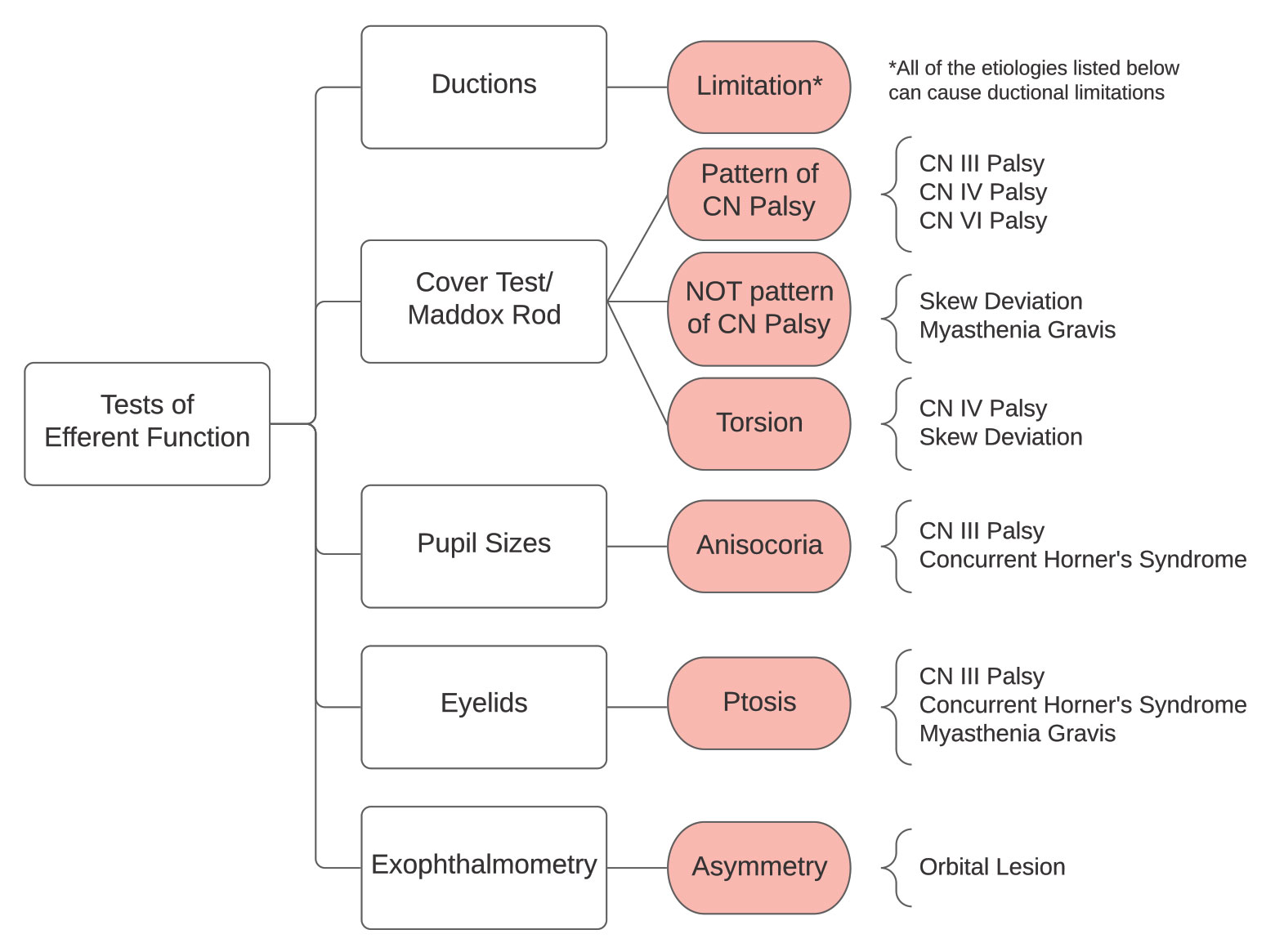

12. Are there any other associated ocular findings? (e.g., vision loss, ptosis, anisocoria, conjunctival injection, proptosis, uveitis, nystagmus, papilledema, signs of aberrant regeneration)

Thorough assessment of other afferent and efferent exam findings can also uncover clues which may help localize the cause of the diplopia. For example, proptosis and monocular vision loss would be more indicative of an orbital lesion or thyroid eye disease, while the presence of ptosis may indicate a CN III palsy, MG or a concurrent Horner’s syndrome. Figure 6 highlights some additional efferent exam findings which are helpful for localization.

On biomicroscopy, the presence of conjunctival injection or a red eye may point to a cavernous sinus fistula, thyroid eye disease or inflammatory orbital pseudotumor. Any signs of a current or previous uveitis may indicate an infectious or inflammatory etiology, such as sarcoidosis, syphilis or lymphoma. Additionally, if a patient presents with a unilateral or bilateral abduction deficit, careful assessment of the optic nerve is necessary to look for any signs of papilledema secondary to increased intracranial pressure.

13. What are the results of a forced duction test?

If a patient presents with an obvious ductional limitation, a forced duction test could be useful in localizing the lesion. If the limitation is due to a restrictive etiology, the provider will be unable to physically move the globe. If the etiology is neurogenic, the globe should move into the desired position of gaze with physical manipulation.

14. Are there any other neurological signs (abnormal CN V, VII or VIII, extremity weakness, headache, ocular pain, ataxia, change in gait)?

To assess for additional neurological signs, it is helpful to complete a short neurological assessment. Break the examination down into five sections: mental status, CN testing, motor/reflex examination, coordination/gait and a general sensory exam.7

The presence of multiple CN involvement is more suggestive of a neurological etiology and can help with the localization of the lesion.

Evidence of additional CN involvement may assist in localizing the lesion (Figure 7). For example, if a patient presents with a left abduction deficit alone, it may be difficult to discern if the lesion is orbital, nerve or brain. However, the concurrent presence of a CN VII palsy would localize the lesion to the only anatomical location where the two nerves are in close proximity, which would be the ventral low pons of the brainstem.

Another localizing feature would be the concurrent presence of decreased sensation on the ipsilateral forehead or cheek, which indicates involvement of the ophthalmic or maxillary divisions of CN V. Anatomically, the location where these branches of CN V are in closest proximity to CN III, IV or VI is the cavernous sinus.

|

| Fig. 5. Double Maddox rod testing showing excyclotorsion of the right eye and no torsion when placed over the left eye, consistent with a right CN IV palsy. Click image to enlarge. |

15. Are there any constitutional signs? (e.g., fatigue, weight loss, fever)

A yes to this question may indicate a systemic etiology and should prompt an urgent work-up. Any patient over the age of 50 who presents with diplopia should be evaluated for giant cell arteritis (GCA).

16. Any known health problems? (e.g., vasculopathic disease, infectious disease, inflammatory disease, cancer)

The etiology of the diplopia may be secondary to an underlying systemic condition, so it is important to obtain a thorough history of known conditions, even if the patient has already been treated or is in remission. Always ask about a history of syphilis, Lyme disease, cancer, sarcoidosis and thyroid disease. For example, a patient with a prior infection of syphilis may develop neurosyphilis and present with new-onset diplopia.

A patient presenting with new-onset diplopia and a history of cancer, even if in remission, should have an urgent work-up. The presence of diplopia may be the first sign of a recurrence.

Vasculopathic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, are well known causes of acute-onset isolated CN palsies. Practitioners must be careful not to assume a vasculopathic etiology without first carefully assessing for other possible etiologies.

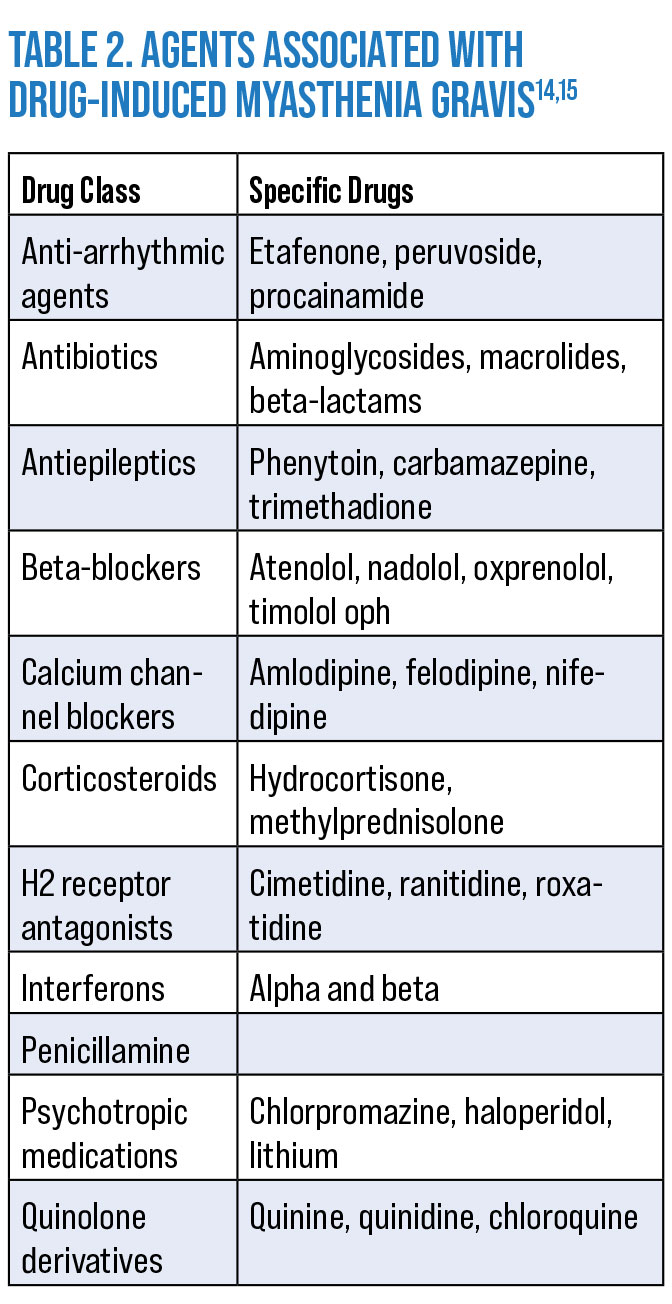

17. Is the patient on any medications known to cause diplopia?

A number of medications are associated with diplopia, though the mechanisms involved are varied and not all well understood (Table 1). There are also drugs that can exacerbate or induce MG (Table 2). A careful review of medication lists is warranted in any new-onset diplopia.

18. Where does this localize to?

The practitioner should now be able to determine if the etiology is localized in the brain, nerve, junction or orbit. The exact etiology may not be known but a differential diagnosis can be created to help answer the questions in Step 4.

|

| Fig. 6. Other efferent findings can aid in localizing the lesion. Click image to enlarge. |

Step 4: Determine Additional Testing/Treatment

19. How urgent is this and what additional testing is warranted?

Generally, any acute-onset diplopia that shows any other abnormalities on exam (i.e., multiple CN involvement, proptosis, pain, significant systemic history) warrants urgent additional testing. The type of testing will depend on the list of differentials created. In many cases, neuroimaging and laboratory testing are necessary.

There is some debate on the necessity of neuroimaging and other additional testing in the setting of isolated CN palsies, particularly in older patients with vasculopathic risk factors. More recent studies have suggested that contrast-enhanced MRI has an important role in the initial evaluation of isolated CN palsies in patient populations of all ages.16-18

20. What can I do to help the patient?

The most important thing an eye care provider can do for a patient with diplopia is to rule out any underlying systemic conditions or potential lesions causing their symptoms. Using the history and exam findings will lead to a list of differentials that can help direct what the next step should be.

Before the patient leaves the office, the provider should also address their current quality of life and visual status. The provider should evaluate if the patient can achieve fusion with prismatic correction. If so, a Fresnel prism can be dispensed. Ground-in prism should not be given until the etiology is determined. If a patient does not respond to prismatic correction, an eye patch or occlusion filter should be dispensed.

|

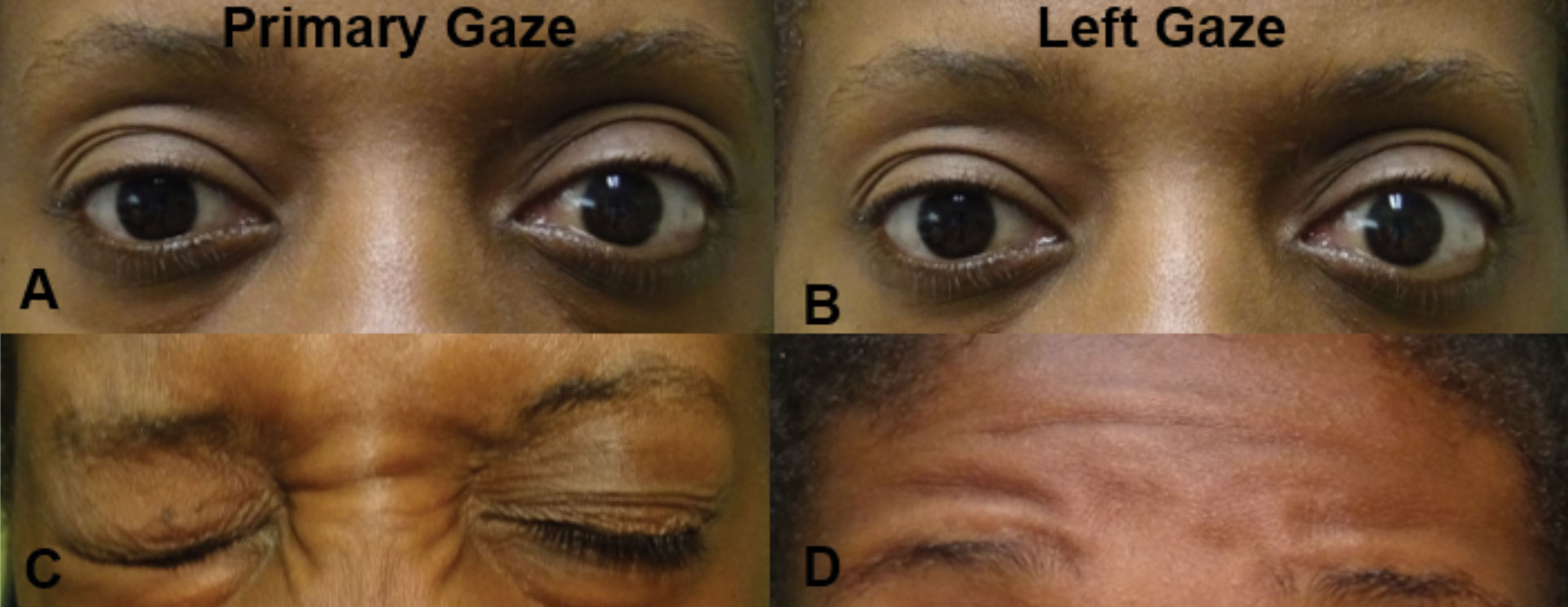

| Fig. 7. In primary gaze (A), there is a noted difference in palpebral apertures due to the left lower lid lagophthalmos. In left gaze (B), there is no movement of either eye consistent with a left gaze palsy (likely at the left CN VI nucleus). There was associated left orbicularis oculi weakness (C) and left frontalis weakness (D), both consistent with a partial left CN VII lesion. The combination of these findings localizes the lesion to the left pons involving both the CN VI nucleus and CN VII fasiculus. Click image to enlarge. |

Case Example

Let’s apply our 20-question guide to a case of a 54-year-old Black man who presents for evaluation of diplopia.

Q1. Does the double vision go away if you cover one eye?

“Yes.” He has been patching his left eye since the onset of his symptoms.

Q2. Does it matter which eye you cover?

“No.” Therefore, this patient has true binocular diplopia and we will now move on to Step 2.

Q3. Is it constant or fluctuating?

“Constant.” Due to the constant nature of his diplopia, we are less suspicious for myasthenia gravis or a decompensated phoria.

Q4. How are the images displaced (horizontal, vertical, diagonal)?

“The images are horizontally displaced.” We are now suspicious for a lesion affecting the medial and/or lateral rectus.

Table 1. Drugs Associated With Diploplia8-13Buproprion Lorazepam Citalopram Lamotrigine Felbamate PD-1 inhibitors Fluoxetine Pergolide Fluoroquinolone Statins Gabapentin Topiramate Interferon therapy |

Q5. Is it worse in any particular distance (near or far) or direction of gaze (left, right, up, down)?

“It is present at all distances but worse at distance and when looking left.”

Since it is worse on left gaze, we can narrow down the location to a right adduction deficit or left abduction deficit. Because the horizontal diplopia is worse at distance, this is more consistent with a left abduction deficit. If we consider that his diplopia is secondary to paresis, then we must consider a left CN VI palsy. If we consider enlargement of an extraocular muscle, then we must consider enlargement of the left medial rectus. An orbital mass must still be considered.

Q6. How long has it been going on for and is it stable, worsening or improving?

“This has been going on for the past three days.” Since this is a case of acute-onset diplopia, we cannot differentiate it from vasculopathy or other etiologies at this point.

Q7. How did you first notice it?

“When I first woke up three days ago.” There does not seem to be any precipitating factor.

Q8. Any history of childhood strabismus or prior orbital surgery?

“No.” Therefore, the diplopia is less likely to be secondary to a decompensating phoria.

Q9. Do I see any ductional limitation?

Ductions were graded on “percent of normal.” Upon examination, there was a -5% of abduction in the left eye only (Figure 8). All other ductions in horizontal and vertical gaze were 100% of normal in each eye. Therefore, this patient’s diplopia is secondary to a left abduction deficit, as we suspected based on the answers to question 5.

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

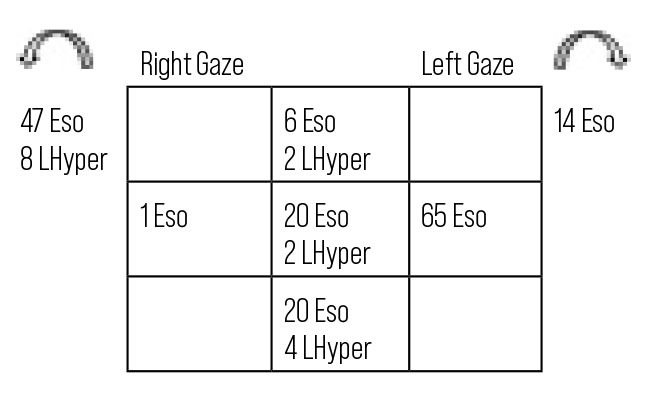

Q10. Does my cover test or Maddox rod testing in different positions of gaze match the pattern of a specific cranial nerve palsy?

Cover test in different positions of gaze revealed an increasing eso deviation in left gaze, which is consistent with a CN VI palsy (Figure 9). It also revealed a left hyper deviation, worse in right head tilt. The hyper deviation did not follow the pattern of a CN IV palsy.

Although it is common to have a small hypertropia with an abducens palsy, further testing with double Maddox rod is indicated given the vertical deviation.19

Q11. Is double Maddox rod testing abnormal?

Double Maddox rod testing revealed 3 excyclotorsion OD and 3 incyclotorsion OS. The hypertropic eye is intorted, which is consistent with a possible skew deviation. Given our examination findings, we must now consider etiologies for both a left CN VI palsy and a left skew deviation and attempt to localize the lesion with additional findings from our examination.

Q12. Are there any associated ocular findings (vision loss, ptosis, anisocoria, conjunctival injections, proptosis, uveitis, nystagmus, papilledema, signs of aberrant regeneration)?

Anterior segment evaluation revealed diffuse keratic precipitates in both eyes, greater and larger in the left eye. The patient reported a history of anterior uveitis in the left eye due to an unknown etiology approximately two years ago. Dilated fundus examination revealed small macular pigment epithelial detachments in both eyes. These findings suggest a possible infectious or inflammatory etiology.

Q13. What are the results of a forced duction test?

Forced duction test was negative. This further supports that it is not an orbital mass.

Q14. Are there any other neurologic signs (abnormal CN V, VII or VIII, extremity weakness, headache, ocular pain, ataxia, change in gait)?

Neurologic examination revealed partial weakness of the left frontalis, left orbicularis oculi and left zygomaticus major. There were no signs of motor, sensory or gait abnormalities. These findings were consistent with a partial CN VII palsy.

|

| Fig. 8. Ductions revealed a left abduction limitation. Click image to enlarge. |

Q15. Are there any constitutional signs (fatigue, weight loss, fever)?

The patient reported losing 10-to-15lbs unintentionally over the course of the last several months. He has also been feeling very fatigued. He denied any headaches, jaw pain, scalp tenderness and fever.

Given his unexplained concurrent weight loss and fatigue, there is likely a systemic etiology contributing to his ocular presentation. Although he denied some symptoms of GCA, we must still consider it as a potential etiology based on his age.

Q16. Any known health problems (vasculopathic disease, infectious disease, inflammatory disease, cancer)?

He denied any history of vasculopathic disease, infectious disease, inflammatory disease and cancer but had not visited a primary care physician in the past three years. Blood pressure was normal on exam.

Q17. Is the patient on any medications known to cause diplopia?

He denied taking any such medications.

Q18. Where does this localize to?

We suspect a left CN VI palsy and a partial left CN VII palsy. The combination of the findings is suggestive of a lesion of the brainstem, specifically in left lower pons. His associated ocular and systemic findings are suggestive of an inflammatory or infectious etiology.

Q19. How urgent is this and what additional testing is warranted?

Given that his diplopia may be secondary to a lesion of the brainstem with a likely systemic inflammatory or infectious etiology, emergent work-up, including neuroimaging and neurology evaluation, is warranted. We recommend an MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast, with focus on the left lower pons and the pathway of CN VI up to and including the orbit.

Furthermore, our concern for inflammatory and infectious conditions necessitates serologic and/or cerebrospinal fluid testing to rule out other causes of diplopia (GCA, Lyme, syphilis, sarcoidosis and autoimmune conditions). We specifically recommend obtaining the following levels: ESR, CRP, Lyme, ANA, RPR, FTA-ABS and ACE. If this testing is inconclusive, we recommend serum testing for myasthenia gravis, including acetylcholine receptor antibody (binding, blocking, modulating).

Q20. What can I do to help the patient?

Prior to transferring his care to the emergency department, we also considered dispensing a Fresnel prism. However, the patient did not appreciate the prismatic correction and preferred to continue to patch his left eye.

After thorough investigation, we found a lesion in the pons accounting for the CN VI and VII palsies. He underwent further pathological evaluation and was ultimately diagnosed with neurosarcoidosis and started on steroid treatment.

|

| Fig. 9. Cover test of patient is consistent with a CN VI palsy. Click image to enlarge. |

To Sum Up

After going through the 20 questions of diplopia outlined here, it is obvious that it is not always an easy task to determine the exact etiology. However, by following this guide, you can ask the necessary questions, keep your thought process logical and organized and create a differential diagnosis. This differential will guide your management of the patient and solve the case.

Dr. Draper is an assistant professor at Salus University. She splits her time between clinical care at The Eye Institute in Philadelphia in the neuro-ophthalmic disease service and teaching anatomy and neuro-ophthalmic disease courses. Dr. Zeng is a resident of neuro-ophthalmic disease at The Eye Institute. They have no financial disclosures.

| 1. Rizzo, M. Baron J. Chapter 13: Central disorders of visual function. In: Miller NR Newman NJ, eds. Walsh and Hoyt’s clinical neuro-ophthalmology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins:621. 2 Goezinne F, La Heij EC, Liem AT, et al. The occurrence and treatment of diplopia after scleral buckling surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(13):6067. 3. Friedman DI. Pearls: diplopia.Semin Neurol. 2010;30(1):54-65. 4. Iliescu DA, Timaru CM, Alexe N, et al. Management of diplopia. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2017;61(3):166-70. 5. Malloy K. Neuro-ophthalmic disease basics: Focus on the efferent visual system evaluation. Rev Optom. 2015;152(2):74-83. 6. Manchandia AM, Demer JL. Sensitivity of the three-step test in diagnosis of superior oblique palsy. J AAPOS. 2014;18(6:567-71. 7. Maglione AK, Seidler KA. The neurological exam: step-by-step. Rev Optom. 2019.;156(2):64-71. 8. Lucca JM, Ramesh M, Parthasarathi G, Ram D. Lorazepam-induced diplopia. Indian J Pharmacol. 2014;46(2):228-9. 9. Roper-Hall G. The influence of the vergence system on strabismus diagnosis and management. Strabismus. 2009;7(1):3-8. 10. Fayyazi Bordbar MR, Jafarzadeh M. Bupropion-induced diplopia in an Iranian patient. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2011;5(2):136-8. 11. Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT. Diplopia and fluoroquinolones. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(9):1814-7. 12. Rajak S, Sullivan T, Selva D. Orbital myositis: a side effect of interferon alpha 2b treatment. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(1):75. 13. Alves M, Miranda A, Narciso MR, Mieiro L, Fonseca T. Diplopia: a diagnostic challenge with common and rare etiologies. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:220-3. 14. Ahmed A, Simmons Z. Drugs which may exacerbate or induce myasthenia gravis: a clinician’s guide. Internet J Neurol. 2008;10(2):1-8. 15. Hussain N, Hussain F, Haque D, Chittivelu S. A diagnosis of late-onset myasthenia gravis unmasked by topical antibiotics. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(4):230‐2. 16. Tamhankar MA, Biousse V, Ying GS, et al. Isolated third, fourth and sixth cranial nerve palsies from presumed microvascular vs. other causes: a prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):2264-9. 17. Elder C, Hainline C, Galetta SL, et al. Isolated abducens nerve palsy: update on evaluation and diagnosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16(8):69. 18. Park KA, Oh SY, Min JH, et al. Cause of acquired onset of diplopia due to isolated third, fourth and sixth cranial nerve palsies in patients aged 20 to 50 years in Korea: a high resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurol Sci. 2019;407:116546. 19. Pihlblad MS, Demer JL. Hypertropia in unilateral isolated abducens palsy. J AAPOS. 2014;18(3):235-40. |